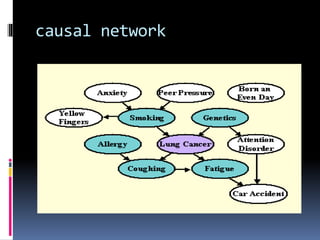

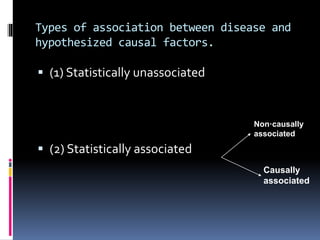

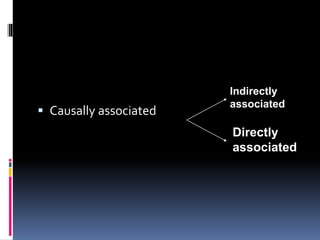

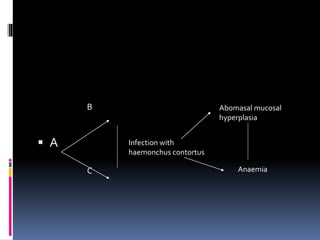

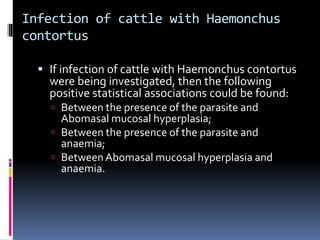

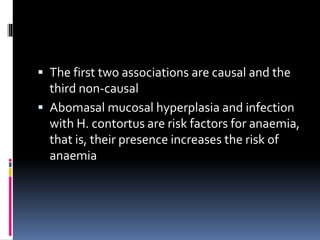

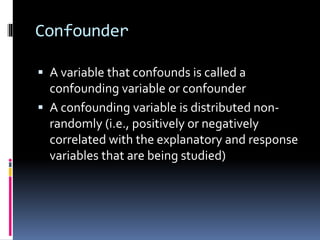

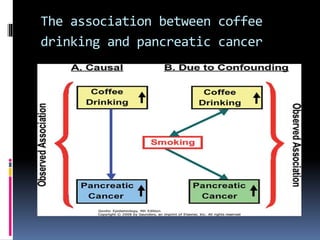

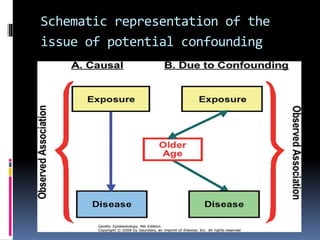

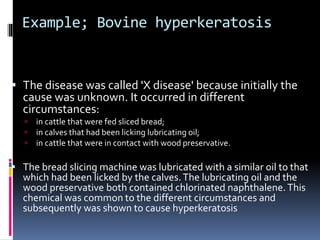

This document discusses variables, study variables, response and explanatory variables, and different types of associations that can exist between variables. It defines statistical and non-statistical associations. It discusses causal relationships between variables and how confounding variables can influence associations. Different causal models are described including sufficient and necessary causes. Guidelines for establishing causal relationships are provided, including Hill's criteria of strength of association, consistency, temporal relationship, biological gradient, and compatibility with existing knowledge.