Embed presentation

Downloaded 1,228 times

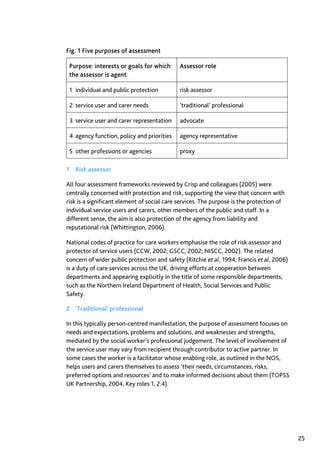

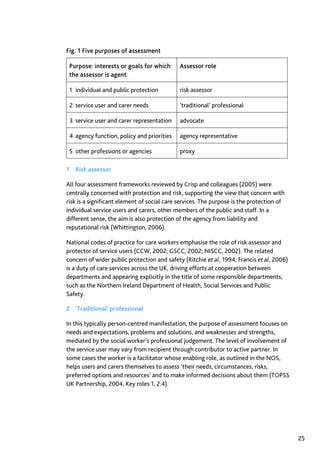

This document provides an overview and guide for teaching and learning about assessment in social work. It covers: 1. The significance of assessment in social work practice and education, and the reasons for teaching and learning about assessment. 2. Key aspects of assessment including definitions, purposes, theories, processes, contexts, service user perspectives, values and ethics. 3. Guidance on teaching and learning content, structure, methods and participants. It emphasizes the need for a combination of abstract theoretical knowledge and concrete skills development, and highlights the importance of involvement from service users, carers, and practice educators. 4. Questions to guide educators on effectively addressing assessment in their teaching, such as exploring different definitions and purposes