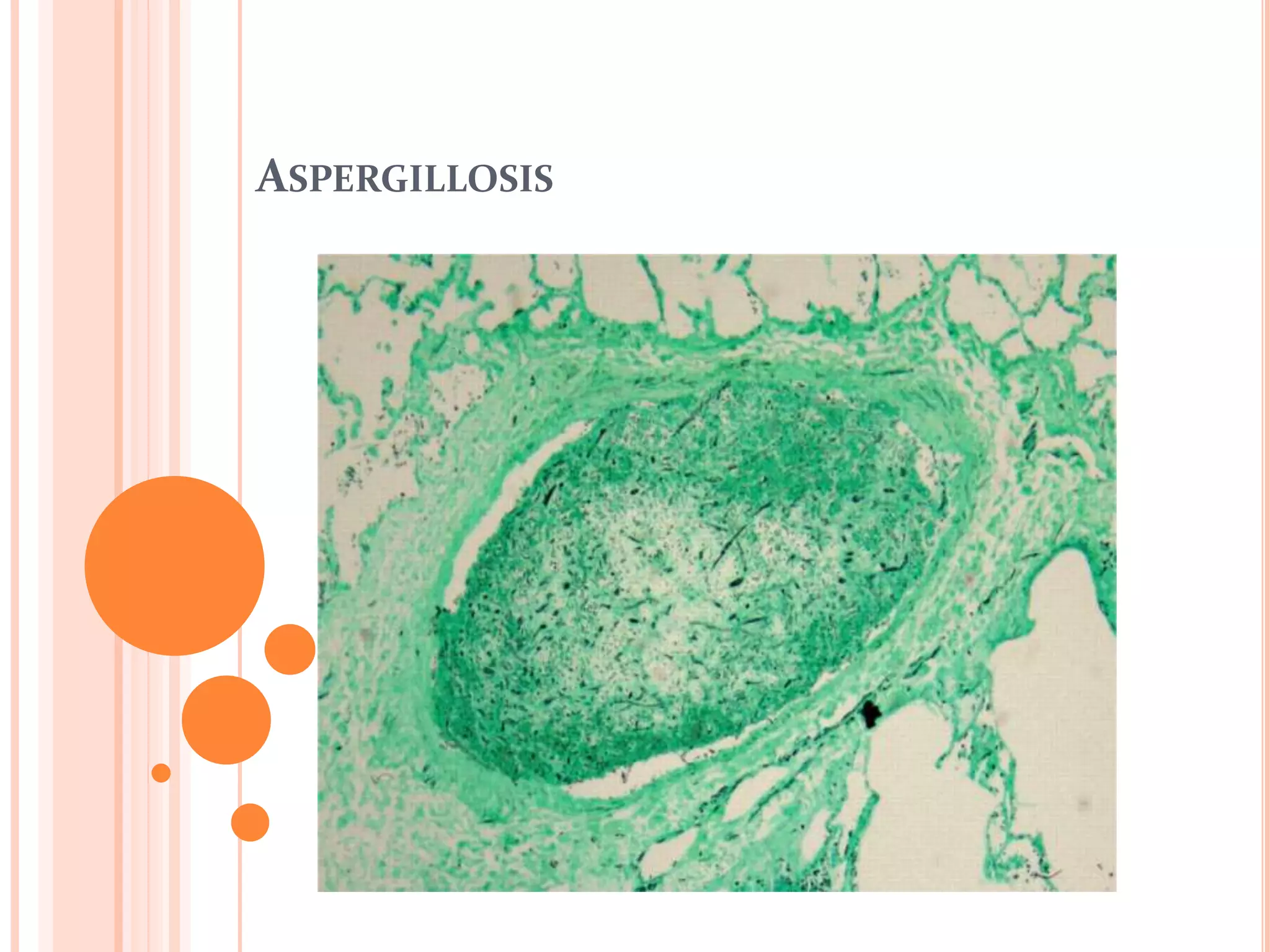

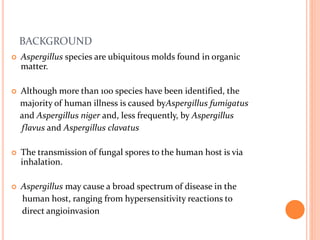

This document summarizes aspergillosis, including invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), chronic necrotizing aspergillosis (CNA), and aspergilloma. Aspergillus is a common mold that can cause a variety of pulmonary diseases. IPA predominantly affects immunocompromised patients and presents as pneumonia. Diagnosis involves tissue biopsy, galactomannan testing, and imaging. Voriconazole is recommended treatment. CNA occurs in patients with underlying lung disease and is characterized by slow lung tissue invasion. Itraconazole is effective treatment. Aspergilloma involves a fungus ball in a pre-existing lung cavity.

![DIAGNOSIS

Histopathological diagnosis, by examining lung tissue

obtained by thoracoscopic or open-lung biopsy, remains the

'gold standard' in the diagnosis of IPA [1]

The significance of isolating Aspergillus sp in sputum samples

depends on the immune status of the host.

Isolation of an Aspergillus species from sputum is highly

predictive of invasive disease in immunocompromised

patients.[2]

[1] Ann Hematol2003;82 Suppl. 2:S141-8.

[2] Am J Med 1996;100:171-8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-9-320.jpg)

![DIAGNOSIS

Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is generally

helpful in the diagnosis of IPA,

The sensitivity and specificity of a positive result of BAL fluid

are about 50% and 97%, respectively. [1]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is another way to diagnose

IPA, by the detection of Aspergillus DNA in BAL fluid and

serum. [2]

A positiveAspergillus PCR in BAL fluid has an estimated sensitivity of

67–100% and specificity of 55–95% for IPA.

PCR sensitivity and specificity have also been reported as 100% and 65–

92%, respectively, in serum samples.

[1] Respir Med 1992;86:243-8.

[2] Br J Haematol 2006;132:478-86](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-16-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

Early initiation of antifungal therapy in patients with strongly

suspected invasive aspergillosis is warranted while a diagnostic

evaluation is conducted [1]

For primary treatment of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, IV or

oral voriconazole is recommended for most patients [2]

[1] IDSA Guidelines Clin Infect Dis. (2008) 46 (3):327-360.

[2] Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of

invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 2002;347:408-15.

Patients receiving voriconazole had a higher 12-week survival

(71% vs. 58% for amphotericin).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-19-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

L-AMB may be considered as alternative primary therapy in some

patients . [1]

For salvage therapy, agents include

LFABs ,

Posaconazole [2],

Itraconazole ,

Echinocandins [caspofungin , or micafungin] [3] .

[1] Amphotericin B lipid complex for invasive fungal infections: analysis of

safety and efficacy in 556 cases. Clin Infect Dis1998;26:1383-96

[2] Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are

refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled

trial. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:2-12

[3] Efficacy and safety of caspofungin for treatment of invasive aspergillosis in

patients refractory to or intolerant of conventional antifungal therapy.

Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1563-71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-20-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

Immunomodulatory therapy, such as using

- colony-stimulating factors (i.e. G-CSF, GM-CSF )[1] or

- interferon-γ [2]

- Granulocyte transfusions [3]

could be used to decrease the degree of immunosuppression,

and as an adjunct to antifungal therapy for the treatment of IPA.

[1] Blood 1995;86:457-62

[2] Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 2000;20:325-34

[3] Med Mycol 2006;44(Suppl):383-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-22-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

Treatment of this infection may prevent progressive destruction

of lung tissue in patients who are already experiencing impaired

pulmonary function and who may have little pulmonary reserve

The greatest body of evidence regarding effective therapy supports the use

of orally administered itraconazole .[1]

Although voriconazole [2](and presumably posaconazole) is also likely to

be effective, there is less published information available for its use in

CNPA

[1] Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:25-30.

[2] Chest2007;131:1435-41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-32-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

Administration of amphotericin B percutaneously guided by CT

scan can be effective for aspergilloma, especially in patients with

massive haemoptysis, with resolution of haemoptysis within few

days. [1]

The role of medical therapy is uncertain Oral itraconazole

or voriconazole may be used [2]

[1] Intern Med 1995;34:85-8

[2] IDSA Guidelines Clin Infect Dis. (2008) 46 (3):327-360](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-43-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

Treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (APBA) should

consist of a combination of corticosteroids and itraconazole.

Corticosteroid therapy is the mainstay of therapy for ABPA , with

improved pulmonary function and fewer episodes of recurrent

consolidation. [1]

Itraconazole has been effective in improving symptoms, facilitating

weaning from corticosteroids, decreasing Aspergillus titres, and

improving radiographic abnormalities and pulmonary function. [2]

[1] Chest 1993;103:1614-7.

[2] A randomized trial of itraconazole in allergic bronchopulmonary

aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 2000;342:756-62.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspergillosis-141020010854-conversion-gate01/85/Aspergillosis-52-320.jpg)