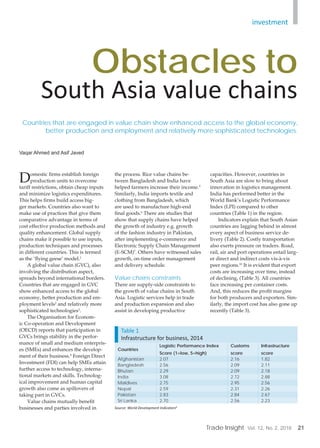

Countries that participate in global and regional value chains can access larger markets and benefit from technology transfer, skills development, and economic stability. However, South Asian countries face obstacles to integrating value chains due to poor logistics services, high trade costs, and lengthy border procedures. Interviews with businesses revealed additional barriers like lack of economic corridors, border conflicts, and non-tariff measures. Strengthening value chains in South Asia will require reforms in trade facilitation, deeper regional trade agreements, and public-private cooperation.