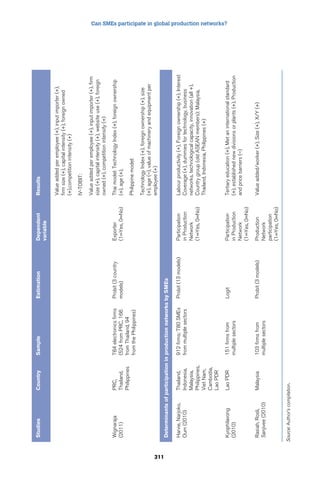

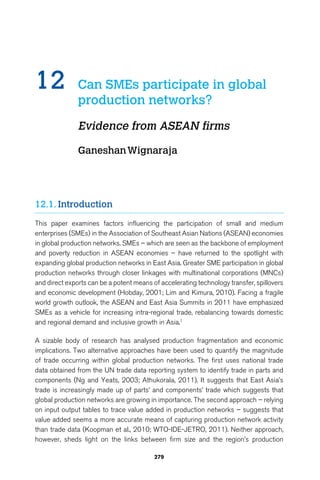

This document is an edited volume on global value chains (GVCs) in a changing world. It contains 16 chapters contributed by experts in the field. The introduction provides an overview of the volume, which aims to examine how GVCs are evolving and the implications for policymakers. Part I looks at changing features of GVCs, including their emergence and growth, as well as the increasing role of services. Part II analyzes methods for measuring trade in value-added terms. Part III discusses issues for GVC managers. Part IV explores policies for integrating into GVCs, including the ability of SMEs and developing countries to participate. The conclusion is that GVCs are in flux and policies must adapt to remain relevant

![Global value chains in a changing world

services and cross-border procedures. While the East Asia region is well ahead of

the rest of developing Asia in this respect, there is still a wide margin of progress

in order to close the gap with best international practices, particularly in terms of

administrative arrangements.

Appendix 5.1. Technical note on average

propagation length

Suppose an n-industrial sector economy with a production structure defined by the

input coefficient matrix A shown in Figure a. Input coefficients aij are calculated from

an input-output table by dividing input values of goods and services used in each

industry by the industry’s corresponding total output, i.e. aij = zij / Xj where zij is a

value of good/service i purchased for the production in industry j, and Xj is the total

output of industry j. So, the coefficients represent the direct requirement of inputs for

producing just one unit of output of industry j.

Figure a An input Coefficient Matrix Figure b Impact delivery paths

152

A =

a a a a

a a a a

a a a a

n

n

n

11 12 13 1

21 22 23 2

31 32 33 3

a n 1 a n a 2 n

3

an

n

1 step path

Ind 3

a13 Ind 1

2 step paths

Ind 3

a23 Ind 2

a12 Ind 1

Ind 3

a33 Ind 2

a13 Ind 1

. . .

. . .

and so on.

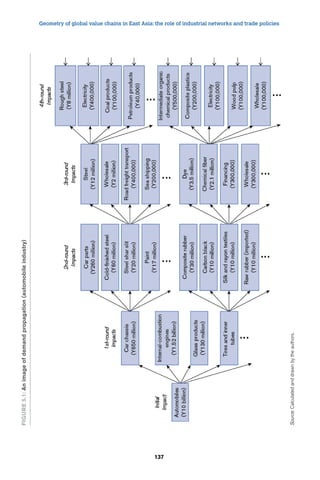

The vertical sequence of demand propagation can be depicted as follows. Let us

consider the impact of demand for 100 units in industry 3 upon the output of industry

1. The simplest form of all is given by the direct linkage [3→1], which is calculated

as a product of multiplying 100 units by input coefficient a13. This is because a13,

by definition of an input coefficient, represents an immediate amount of products of

industry 1 required for producing just one unit of products of industry 3. Alternatively,

there is a two-step path going through another industry, say, [3→2→1]. This is derived

by two-stage multiplication, i.e. 100 units by a23, and then by a12. There can also be a

two-step path going through the same industry, such as [3→3→1] or [3→1→1] which

would be derived respectively as “100 × a33 × a13” and “100 × a13 × a11” (see Figure b).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-177-320.jpg)

![Geometry of global value chains in East Asia: the role of industrial networks and trade policies

The exercise reveals that the impact of any two-step path, whatever the sequence

of industries, can be given by feeding back a set of direct impacts, A, into the input

coefficient matrix, i.e. A × A = A2. Similarly, the impact of three-step paths is given by

A × A2 = A3, that of four-step paths by A × A3 = A4 and so on, which is evident from

[A2]ij=Σkaikakh, [A3]ij=ΣkΣhaikakhahj, etc. The amount of impacts shown in each layer of Aks

(k=1, 2, 3,...,) is a result of the initial demand injection passing through all k-step paths.

It captures the effect of every direct and indirect linkage that undergoes exactly the

k-round steps/stages of the production process.

Meanwhile, it is mathematically known that the Leontief inverse matrix L, which shows

the total amount of goods and services required for the production of one unit of

output, can be expanded as an arithmetic series, i.e. L = (I – A)–1 = I + A + A2 + A3 +

A4 + ..., where I is an identity matrix (with “1” in diagonal elements and “0” elsewhere).

From what we saw above, it is immediately clear that the equation represents the

decomposition of the total impact on output into its constituent layers according

to the number of production stages involved. Matrix I corresponds to an initial (unit)

demand injection and the following Aks are regarded as progressive impacts of the

initial demand when supply chains are sliced at the kth stage of the production process.

With this preliminary understanding, Average Propagation Lengths are specified as:

APL(j-i) = 1*aij / (lij – δij)+ 2*[A2]ij / (lij – δij) + 3*[A3]ij / (lij – δij)+ ...

A A

153

=

k k

= ij

=

k

k 1 k 1

ij

[2]

where A is an input coefficient matrix, aij is its elements, lij is Leontief inverse

coefficients, δij is a Kronecker delta which is δij=1 if i=j and δij=0 otherwise, and k

is a number of production stages along the path. We also define APL(j-i)=0 when

(lij – δij) =0.

The first term in the right-hand side of the upper equation shows that the impact

delivered through one-step paths (k=1), i.e. direct impact, amounts to aij / (lij – δij)

share of the total impact given by the Leontief inverse coefficients (less unity for

diagonal elements). Similarly, two-step paths (k=2) contribute [A2]ij / (lij – δij) share,

and three-step paths (k=3) give [A3]ij/ (lij – δij) share of the total impact. This is evident

from L = I + A + A2 + A3 + ... which is rearranged as L – I = A + A2 + A3 + ..., and hence

(L – I)ij = (lij – δij) = Aij+ [A2]ij+ [A3]ij+ ....](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-178-320.jpg)

![Global value chains in a changing world

That is, Average Propagation Lengths is formulated as a weighted average of the

number of production stages which an impact from industry j goes through until it

ultimately reaches industry i, using the share of an impact at each stage as a weight.

Appendix 5.2. Effective protection rates and anti-export

j i i ij

( )+ ( )

j i i

f

ij i i

. .

154

bias

EPR for sector “j” is the difference between the nominal protection enjoyed on the

output minus the weighted average of tariff paid on the required inputs.

It is given by:

EPR

t t a

j a

i ij

=

−

−

( )

1

.

[3]

With aij : elements of the matrix A of technical coefficients in an input-output matrix,

tj : nominal tariff on sector “j”,

ti : nominal tariff on inputs purchased from sector “i”. “i” can be equal to “j” when a firm

purchases inputs from other firms of the same sector of activity. In an inter-country

framework, “i” includes also the partner dimension [c] as inputs from sector “i” might

be domestic or imported.

Note that [1 - Σiaij ] is the rate of sectoral value added per unit of output when there is

no tariff and the domestic prices of tradable goods are similar to the international ones

(free trade). Therefore, EPRs are the ratio of the value added obtained considering

the given (applied) tariff schedules compared to a situation of free trade and no tariff.

It can be negative when firms pay a high tariff on their inputs but have a low nominal

protection on their output.

Tariff duties influence the domestic price of all inputs, including domestically produced.

Domestic suppliers of tradable goods will be able to raise their own prices up to the

level of the international price plus the tariff duty, without running the risk of being

displaced by imports. Distinguishing between domestic and foreign inputs, EPR can

therefore be written as:

EPR

t ta t a

j a

h

ij

i ij

=

−

−

1

[4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-179-320.jpg)

![Geometry of global value chains in East Asia: the role of industrial networks and trade policies

t a t a

a

a ta

a

155

With af

ij and ah

ij the intermediate consumption “i” from, respectively, foreign and home

country required to produce one unit of output “j”.

From a “trade in tasks” perspective, we can deduce two important conclusions from

equation [4]:

(i) A high positive EPR reduces protected sectors’ incentive to export, as their rate

of return on the domestic market is higher than what they can expect on the

international one. Similarly, an exporting firm will be in an inferior position vis à

vis a foreign competitor operating in a free trade environment, as its value-added

when selling at world price is lower than its free-trade competitor, as shown in [5].

1 ( )+ ( )

1

1

. . −

−

i i

f

ij i i

h

ij

i ij

[5]

(ii) When duty draw-backs or tariff exemption (as in export processing zones) correct

for this bias and allow domestic producers to purchase inputs at international

prices, export-oriented firms still have a disincentive to purchase inputs internally

as their second-tier domestic suppliers won’t be able to benefit from the duty

exemption (see [6]).9

1 + ( )

1

1

. −

−

i

f

ij i i

h

ij

i ij

[6]

While the anti-export bias [5] is a well-known result from a traditional trade in final

goods perspective, new corollary [6] is relevant only from a vertical specialization

perspective, where a “buy” decision arising from a “make or buy” assessment implies

arbitraging between domestic and foreign suppliers.

Endnotes

1 The reason for using the impact shares as weights is as follows. If a calculated share is small, this

implies that the corresponding path has a small contribution to the overall circuit of impact delivery;

so this path is considered relatively insignificant in the supply chains and hence the number of

production stages it has should be weighted less.

2 A more extensive analysis was carried out in Romero et al. (2009), in which the effects of

fragmentation on the complexity of the Chicago economy were studied from a set of input-output

tables estimated for the period 1978–2014.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-180-320.jpg)

![Global value chains in a changing world

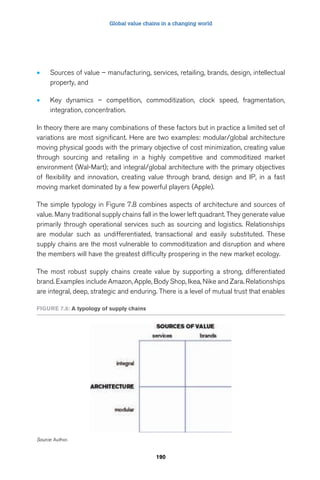

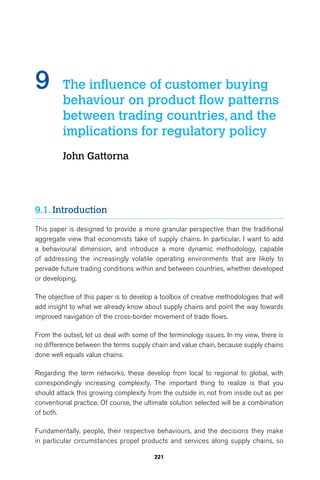

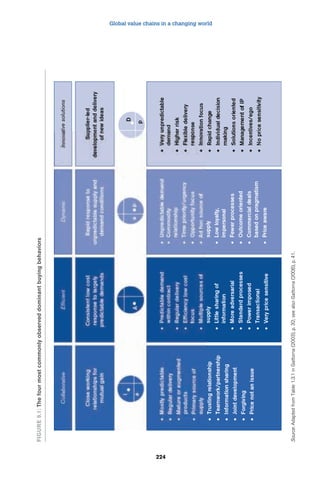

Paradoxically, company executives, thinking that more standardization of processes

and underlying systems would reduce the complexity they face, have in fact made

things worse as the new [more rigid] systems installed have further reduced the

degree of natural “alignment” with customers, and in so doing led to more exceptions,

increased cost-to-serve, and more (rather than less) complexity. This is a good

example of what happens when attempting to fix a problem from the inside out.

At the country level, complexity has arisen simply because of the rate of growth

that has occurred in the process swamping existing capabilities. China is a good

example of this. India is another example that is in an even worse situation because

of its poor infrastructure. At least China has made giant advances in this particular

area. Yet both countries lag in finding solutions to smooth the flow of trade

through their inbound and outbound supply chains as evidenced by their low

standing in the Ease of Doing Business Index referred to later in this paper. See

Lawrence et al., (2012).

Fortunately, we now have at our disposal network optimization modelling techniques

that have the potential to cut through complexity and allow us to in effect find

the lowest cost pathways through nominated networks, from the supply base to

customers, anywhere in the world. These mixed integer mathematical models have

been available for the last few decades, but it has taken the hardware on which

they run time to catch up and achieve the required higher processing speeds. The

best models currently available are designed by Solvoyo (Boston) and Llamasoft

(Ann Arbor).

In addition, instead of running the models against some arbitrary objective function,

we can link them to the behavioural segmentation mentioned above and in the

process find out what the possible pathways and corresponding cost-to-serve are

for any given product-market combinations, under particular operating conditions,

including government taxes or incentives, tariffs and carbon footprint. Indeed, there

is practically no scenario that we cannot model these days, and the result is a whole

new level of more informed decision-making by executives and government officials.

These new Decision Support Systems (DSS) are likely to provide a bright new avenue

for exploring government policy options in the future, especially where constraints

are placed on trading flows across borders. The core concern is to be in a position

to make more informed decisions, and for confirmation of this you only have to look

around the world at the winning sporting teams who benefit by making better, faster

and more timely decisions than their opponents in the heat of competition.

228](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-253-320.jpg)

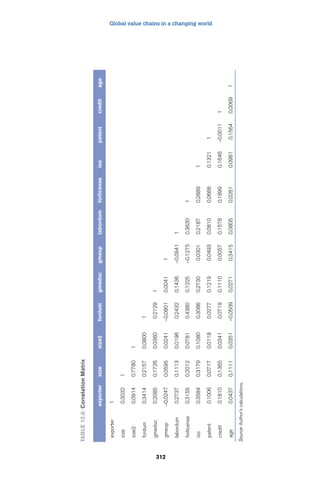

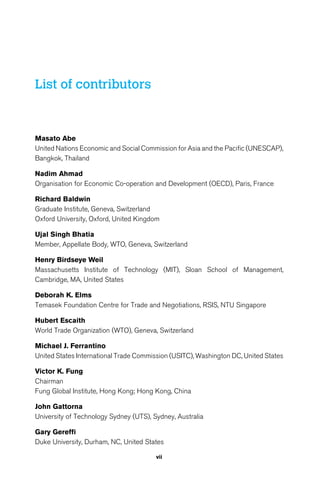

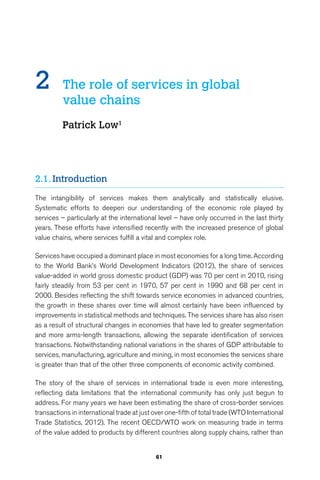

![Global value chains in a changing world

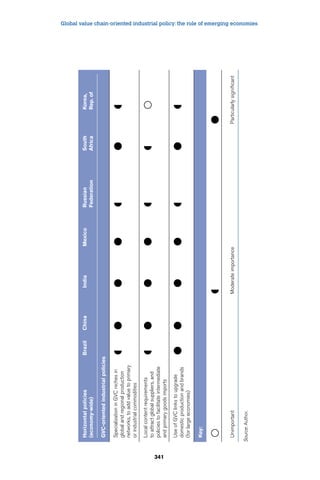

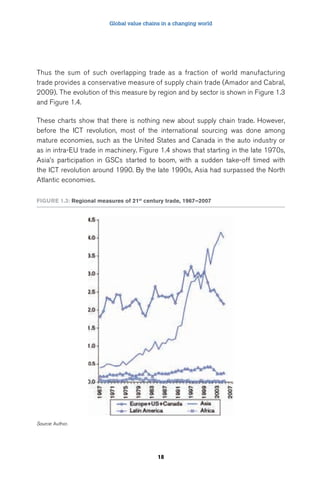

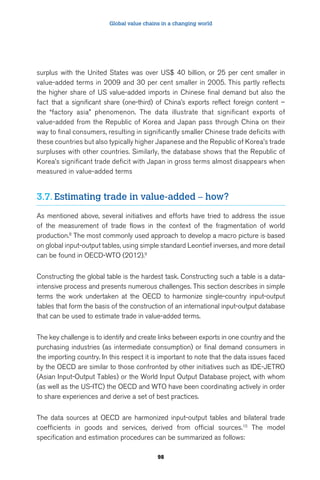

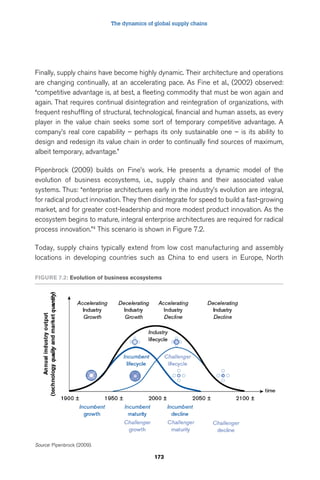

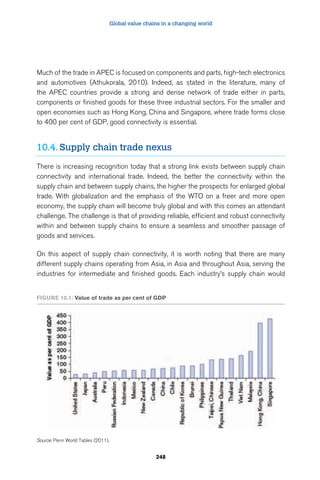

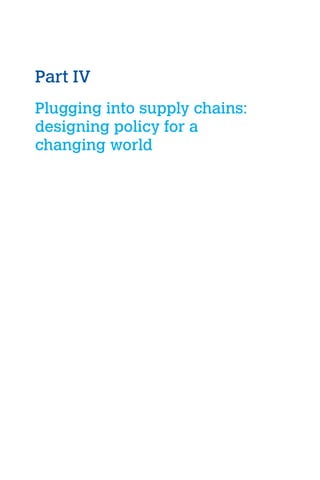

Table 12.5: Probit estimates

Binary Variable: 1 if part of production network, 0 otherwise

SMEs only All firms

All firms in PN Sustained

296

exporter

All firms in PN Sustained

exporter

All All All All

[1] [2] [3] [4]

Firm size 0.012*** 0.010*** 0.002*** 0.001***

(0.001) (0.001) (0.000) (0.000)

Firm size squared -0.000*** -0.000***

(0.000) (0.000)

Foreign ownership 0.547*** 0.500*** 0.566*** 0.533***

(0.071) (0.081) (0.050) (0.053)

GM has primary education 0.329 0.070 0.167 0.131

(0.415) (0.499) (0.285) (0.365)

GM has secondary 0.482 0.086 0.372 0.256

(0.404) (0.487) (0.273) (0.351)

GM has vocational degree 0.538 0.156 0.516* 0.387

(0.407) (0.491) (0.276) (0.354)

GM has college degree 0.515 0.159 0.595** 0.564

(0.403) (0.484) (0.272) (0.349)

GM’s experience 0.003 0.007** 0.003 0.005**

(0.003) (0.003) (0.002) (0.002)

Workers have HS

education

0.255*** 0.162** 0.181*** 0.053

(0.059) (0.071) (0.045) (0.050)

Firm uses foreign licenses 0.196*** 0.093 0.169*** 0.027

(0.073) (0.087) (0.055) (0.061)

Firm is ISO certified 0.311*** 0.144* 0.403*** 0.100*

(0.071) (0.084) (0.049) (0.053)

Firm has registered

patents

0.218*** 0.055 0.331*** 0.063

(0.073) (0.090) (0.056) (0.062)

Access to credit 0.094* -0.005 0.141*** 0.045

(0.054) (0.066) (0.042) (0.046)

Firm Age -0.004* -0.011*** -0.004* -0.009***

(0.003) (0.003) (0.002) (0.002)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-321-320.jpg)

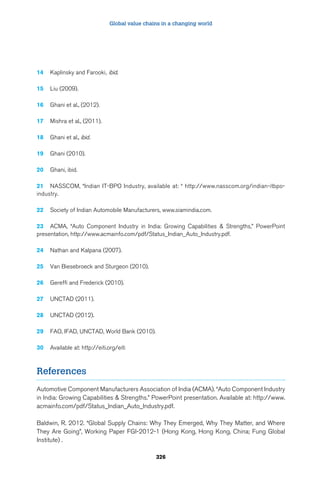

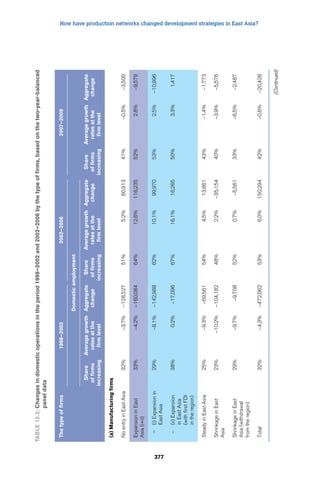

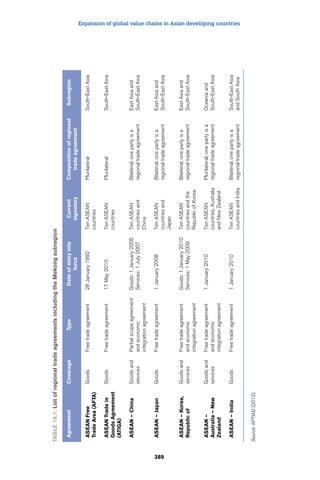

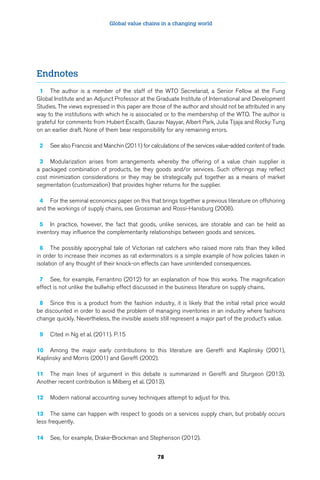

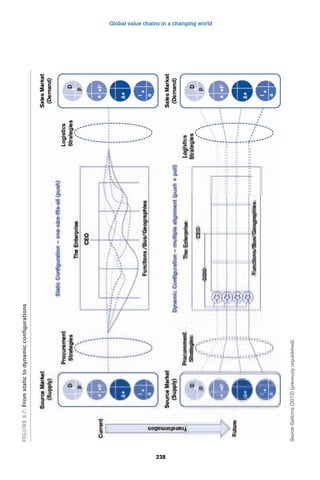

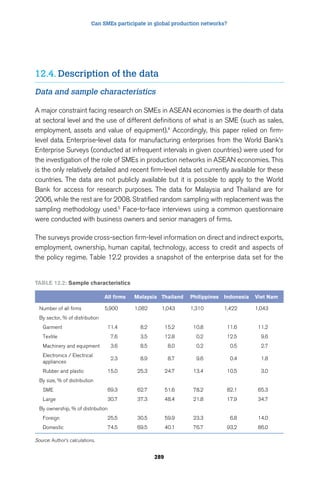

![Can SMEs participate in global production networks?

SMEs only All firms

All firms in PN Sustained

297

exporter

All firms in PN Sustained

exporter

All All All All

[1] [2] [3] [4]

Philippines 0.260** 0.143 -0.201** -0.166*

(0.110) (0.126) (0.080) (0.085)

Indonesia -0.130 -0.322** -0.399*** -0.391***

(0.117) (0.143) (0.082) (0.091)

Viet Nam 0.425*** 0.060 0.156* -0.099

(0.112) (0.133) (0.080) (0.087)

Malaysia 0.841*** 0.526*** 0.634*** 0.452***

(0.094) (0.107) (0.068) (0.070)

Pseudo-R-squared 0.205 0.146 0.267 0.178

N 3,903 3,903 5,641 5,641

* p 0.1, ** p 0.05, *** p 0.01

Robust standard errors in parentheses

Thailand was used as reference.

All firms in PN 1 if more than 0 % of sales are exported (directly or indirectly); 0 otherwise

Sustained exporter 1 if more than 40 % of sales are directly exported; 0 otherwise

Source: Author’s calculations.

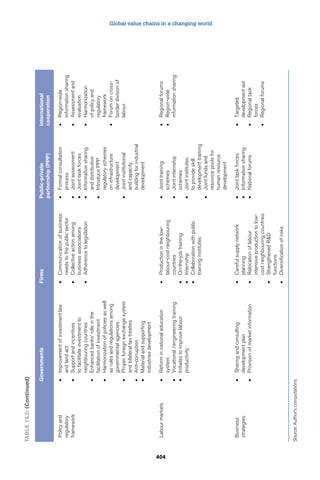

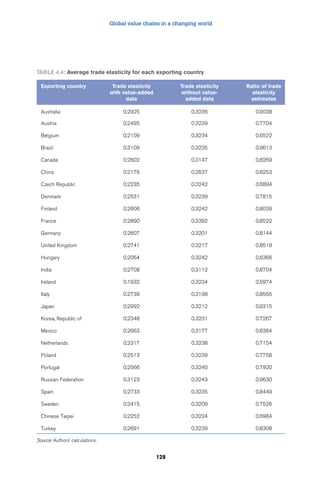

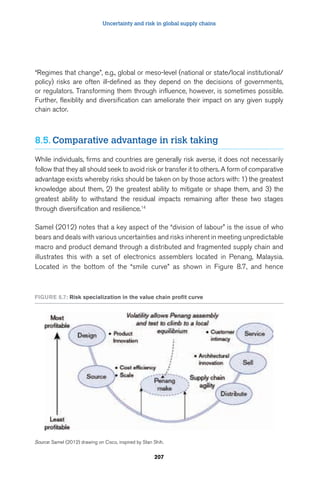

The foreign ownership variable has a positive and significant effect on the probability

of SME participation in production networks in both models. Having any proportion of

foreign equity corresponds to a 31 per cent probability of an SME joining a production

network in the all-SMEs model one (column one). This is double the 15 per cent

figure for a wholly-domestically-owned SME. Access to the superior marketing

connections and know-how of parents enables direct and indirect exporting by

SMEs. Furthermore, access to parents’ accumulated learning experience of export

production as well as access to sophisticated technologies and management

experience improves technical efficiency in SMEs.

The coefficient on workers high school education is positive and significant in both

models. Having a high school-educated workforce increases the probability of an

SME joining a production network from 14 per cent to 21 per cent in the all-SMEs

model one. Furthermore, the CEO’s experience is positive and significant in the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aid4tradeglobalvalue13e-140909015815-phpapp01/85/Aid4tradeglobalvalue13-e-322-320.jpg)