The document discusses the application of deep learning in healthcare, specifically for diagnosing lung cancer types and predicting acute kidney injury. It highlights a study where a deep convolutional neural network was developed to classify lung cancer subtypes and accurately predict mutations, achieving performance comparable to pathologists. Additionally, a model for continuous prediction of acute kidney injury was demonstrated, predicting a significant percentage of cases ahead of time, which could improve patient outcomes.

![ARTICLES

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0177-5

1

Applied Bioinformatics Laboratories, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 2

Skirball Institute, Department of Cell Biology,

New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 3

Department of Pathology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

4

School of Mechanical Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Zografou, Greece. 5

Institute for Systems Genetics, New York University School

of Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 6

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY,

USA. 7

Center for Biospecimen Research and Development, New York University, New York, NY, USA. 8

Department of Population Health and the Center for

Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 9

These authors contributed equally to this work:

Nicolas Coudray, Paolo Santiago Ocampo. *e-mail: narges.razavian@nyumc.org; aristotelis.tsirigos@nyumc.org

A

ccording to the American Cancer Society and the Cancer

Statistics Center (see URLs), over 150,000 patients with lung

cancer succumb to the disease each year (154,050 expected

for 2018), while another 200,000 new cases are diagnosed on a

yearly basis (234,030 expected for 2018). It is one of the most widely

spread cancers in the world because of not only smoking, but also

exposure to toxic chemicals like radon, asbestos and arsenic. LUAD

and LUSC are the two most prevalent types of non–small cell lung

cancer1

, and each is associated with discrete treatment guidelines. In

the absence of definitive histologic features, this important distinc-

tion can be challenging and time-consuming, and requires confir-

matory immunohistochemical stains.

Classification of lung cancer type is a key diagnostic process

because the available treatment options, including conventional

chemotherapy and, more recently, targeted therapies, differ for

LUAD and LUSC2

. Also, a LUAD diagnosis will prompt the search

for molecular biomarkers and sensitizing mutations and thus has

a great impact on treatment options3,4

. For example, epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, present in about 20% of

LUAD, and anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase (ALK)

rearrangements, present in<5% of LUAD5

, currently have tar-

geted therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA)6,7

. Mutations in other genes, such as KRAS and tumor pro-

tein P53 (TP53) are very common (about 25% and 50%, respec-

tively) but have proven to be particularly challenging drug targets

so far5,8

. Lung biopsies are typically used to diagnose lung cancer

type and stage. Virtual microscopy of stained images of tissues is

typically acquired at magnifications of 20×to 40×, generating very

large two-dimensional images (10,000 to>100,000 pixels in each

dimension) that are oftentimes challenging to visually inspect in

an exhaustive manner. Furthermore, accurate interpretation can be

difficult, and the distinction between LUAD and LUSC is not always

clear, particularly in poorly differentiated tumors; in this case, ancil-

lary studies are recommended for accurate classification9,10

. To assist

experts, automatic analysis of lung cancer whole-slide images has

been recently studied to predict survival outcomes11

and classifica-

tion12

. For the latter, Yu et al.12

combined conventional thresholding

and image processing techniques with machine-learning methods,

such as random forest classifiers, support vector machines (SVM) or

Naive Bayes classifiers, achieving an AUC of ~0.85 in distinguishing

normal from tumor slides, and ~0.75 in distinguishing LUAD from

LUSC slides. More recently, deep learning was used for the classi-

fication of breast, bladder and lung tumors, achieving an AUC of

0.83 in classification of lung tumor types on tumor slides from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)13

. Analysis of plasma DNA values

was also shown to be a good predictor of the presence of non–small

cell cancer, with an AUC of ~0.94 (ref. 14

) in distinguishing LUAD

from LUSC, whereas the use of immunochemical markers yields an

AUC of ~0.94115

.

Here, we demonstrate how the field can further benefit from deep

learning by presenting a strategy based on convolutional neural

networks (CNNs) that not only outperforms methods in previously

Classification and mutation prediction from

non–small cell lung cancer histopathology

images using deep learning

Nicolas Coudray 1,2,9

, Paolo Santiago Ocampo3,9

, Theodore Sakellaropoulos4

, Navneet Narula3

,

Matija Snuderl3

, David Fenyö5,6

, Andre L. Moreira3,7

, Narges Razavian 8

* and Aristotelis Tsirigos 1,3

*

Visual inspection of histopathology slides is one of the main methods used by pathologists to assess the stage, type and sub-

type of lung tumors. Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) are the most prevalent subtypes of lung

cancer, and their distinction requires visual inspection by an experienced pathologist. In this study, we trained a deep con-

volutional neural network (inception v3) on whole-slide images obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas to accurately and

automatically classify them into LUAD, LUSC or normal lung tissue. The performance of our method is comparable to that of

pathologists, with an average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.97. Our model was validated on independent datasets of frozen

tissues, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues and biopsies. Furthermore, we trained the network to predict the ten most

commonly mutated genes in LUAD. We found that six of them—STK11, EGFR, FAT1, SETBP1, KRAS and TP53—can be pre-

dicted from pathology images, with AUCs from 0.733 to 0.856 as measured on a held-out population. These findings suggest

that deep-learning models can assist pathologists in the detection of cancer subtype or gene mutations. Our approach can be

applied to any cancer type, and the code is available at https://github.com/ncoudray/DeepPATH.

NATURE MEDICINE | www.nature.com/naturemedicine

LETTER https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1390-1

A clinically applicable approach to continuous

prediction of future acute kidney injury

Nenad Tomašev1

*, Xavier Glorot1

, Jack W. Rae1,2

, Michal Zielinski1

, Harry Askham1

, Andre Saraiva1

, Anne Mottram1

,

Clemens Meyer1

, Suman Ravuri1

, Ivan Protsyuk1

, Alistair Connell1

, Cían O. Hughes1

, Alan Karthikesalingam1

,

Julien Cornebise1,12

, Hugh Montgomery3

, Geraint Rees4

, Chris Laing5

, Clifton R. Baker6

, Kelly Peterson7,8

, Ruth Reeves9

,

Demis Hassabis1

, Dominic King1

, Mustafa Suleyman1

, Trevor Back1,13

, Christopher Nielson10,11,13

, Joseph R. Ledsam1,13

* &

Shakir Mohamed1,13

The early prediction of deterioration could have an important role

in supporting healthcare professionals, as an estimated 11% of

deaths in hospital follow a failure to promptly recognize and treat

deteriorating patients1

. To achieve this goal requires predictions

of patient risk that are continuously updated and accurate, and

delivered at an individual level with sufficient context and enough

time to act. Here we develop a deep learning approach for the

continuous risk prediction of future deterioration in patients,

building on recent work that models adverse events from electronic

health records2–17

and using acute kidney injury—a common and

potentially life-threatening condition18

—as an exemplar. Our

model was developed on a large, longitudinal dataset of electronic

health records that cover diverse clinical environments, comprising

703,782 adult patients across 172 inpatient and 1,062 outpatient

sites. Our model predicts 55.8% of all inpatient episodes of acute

kidney injury, and 90.2% of all acute kidney injuries that required

subsequent administration of dialysis, with a lead time of up to

48 h and a ratio of 2 false alerts for every true alert. In addition

to predicting future acute kidney injury, our model provides

confidence assessments and a list of the clinical features that are most

salient to each prediction, alongside predicted future trajectories

for clinically relevant blood tests9

. Although the recognition and

prompt treatment of acute kidney injury is known to be challenging,

our approach may offer opportunities for identifying patients at risk

within a time window that enables early treatment.

Adverse events and clinical complications are a major cause of mor-

tality and poor outcomes in patients, and substantial effort has been

made to improve their recognition18,19

. Few predictors have found their

way into routine clinical practice, because they either lack effective

sensitivity and specificity or report damage that already exists20

. One

example relates to acute kidney injury (AKI), a potentially life-threat-

ening condition that affects approximately one in five inpatient admis-

sions in the United States21

. Although a substantial proportion of cases

of AKI are thought to be preventable with early treatment22

, current

algorithms for detecting AKI depend on changes in serum creatinine

as a marker of acute decline in renal function. Increases in serum cre-

atinine lag behind renal injury by a considerable period, which results

in delayed access to treatment. This supports a case for preventative

‘screening’-type alerts but there is no evidence that current rule-based

alerts improve outcomes23

. For predictive alerts to be effective, they

must empower clinicians to act before a major clinical decline has

occurred by: (i) delivering actionable insights on preventable condi-

tions; (ii) being personalized for specific patients; (iii) offering suffi-

cient contextual information to inform clinical decision-making; and

(iv) being generally applicable across populations of patients24

.

Promising recent work on modelling adverse events from electronic

health records2–17

suggests that the incorporation of machine learning

may enable the early prediction of AKI. Existing examples of sequential

AKI risk models have either not demonstrated a clinically applicable

level of predictive performance25

or have focused on predictions across

a short time horizon that leaves little time for clinical assessment and

intervention26

.

Our proposed system is a recurrent neural network that operates

sequentially over individual electronic health records, processing the

data one step at a time and building an internal memory that keeps

track of relevant information seen up to that point. At each time point,

the model outputs a probability of AKI occurring at any stage of sever-

ity within the next 48 h (although our approach can be extended to

other time windows or severities of AKI; see Extended Data Table 1).

When the predicted probability exceeds a specified operating-point

threshold, the prediction is considered positive. This model was trained

using data that were curated from a multi-site retrospective dataset of

703,782 adult patients from all available sites at the US Department of

Veterans Affairs—the largest integrated healthcare system in the United

States. The dataset consisted of information that was available from

hospital electronic health records in digital format. The total number of

independent entries in the dataset was approximately 6 billion, includ-

ing 620,000 features. Patients were randomized across training (80%),

validation (5%), calibration (5%) and test (10%) sets. A ground-truth

label for the presence of AKI at any given point in time was added

using the internationally accepted ‘Kidney Disease: Improving Global

Outcomes’ (KDIGO) criteria18

; the incidence of KDIGO AKI was

13.4% of admissions. Detailed descriptions of the model and dataset

are provided in the Methods and Extended Data Figs. 1–3.

Figure 1 shows the use of our model. At every point throughout an

admission, the model provides updated estimates of future AKI risk

along with an associated degree of uncertainty. Providing the uncer-

tainty associated with a prediction may help clinicians to distinguish

ambiguous cases from those predictions that are fully supported by the

available data. Identifying an increased risk of future AKI sufficiently

far in advance is critical, as longer lead times may enable preventative

action to be taken. This is possible even when clinicians may not be

actively intervening with, or monitoring, a patient. Supplementary

Information section A provides more examples of the use of the model.

With our approach, 55.8% of inpatient AKI events of any severity

were predicted early, within a window of up to 48 h in advance and with

a ratio of 2 false predictions for every true positive. This corresponds

to an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 92.1%,

and an area under the precision–recall curve of 29.7%. When set at this

threshold, our predictive model would—if operationalized—trigger a

1

DeepMind, London, UK. 2

CoMPLEX, Computer Science, University College London, London, UK. 3

Institute for Human Health and Performance, University College London, London, UK. 4

Institute of

Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, London, UK. 5

University College London Hospitals, London, UK. 6

Department of Veterans Affairs, Denver, CO, USA. 7

VA Salt Lake City Healthcare

System, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 8

Division of Epidemiology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 9

Department of Veterans Affairs, Nashville, TN, USA. 10

University of Nevada School of

Medicine, Reno, NV, USA. 11

Department of Veterans Affairs, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 12

Present address: University College London, London, UK. 13

These authors contributed equally: Trevor Back,

Christopher Nielson, Joseph R. Ledsam, Shakir Mohamed. *e-mail: nenadt@google.com; jledsam@google.com

1 1 6 | N A T U R E | V O L 5 7 2 | 1 A U G U S T 2 0 1 9

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm

for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy

in Retinal Fundus Photographs

Varun Gulshan, PhD; Lily Peng, MD, PhD; Marc Coram, PhD; Martin C. Stumpe, PhD; Derek Wu, BS; Arunachalam Narayanaswamy, PhD;

Subhashini Venugopalan, MS; Kasumi Widner, MS; Tom Madams, MEng; Jorge Cuadros, OD, PhD; Ramasamy Kim, OD, DNB;

Rajiv Raman, MS, DNB; Philip C. Nelson, BS; Jessica L. Mega, MD, MPH; Dale R. Webster, PhD

IMPORTANCE Deep learning is a family of computational methods that allow an algorithm to

program itself by learning from a large set of examples that demonstrate the desired

behavior, removing the need to specify rules explicitly. Application of these methods to

medical imaging requires further assessment and validation.

OBJECTIVE To apply deep learning to create an algorithm for automated detection of diabetic

retinopathy and diabetic macular edema in retinal fundus photographs.

DESIGN AND SETTING A specific type of neural network optimized for image classification

called a deep convolutional neural network was trained using a retrospective development

data set of 128 175 retinal images, which were graded 3 to 7 times for diabetic retinopathy,

diabetic macular edema, and image gradability by a panel of 54 US licensed ophthalmologists

and ophthalmology senior residents between May and December 2015. The resultant

algorithm was validated in January and February 2016 using 2 separate data sets, both

graded by at least 7 US board-certified ophthalmologists with high intragrader consistency.

EXPOSURE Deep learning–trained algorithm.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm for detecting

referable diabetic retinopathy (RDR), defined as moderate and worse diabetic retinopathy,

referable diabetic macular edema, or both, were generated based on the reference standard

of the majority decision of the ophthalmologist panel. The algorithm was evaluated at 2

operating points selected from the development set, one selected for high specificity and

another for high sensitivity.

RESULTS TheEyePACS-1datasetconsistedof9963imagesfrom4997patients(meanage,54.4

years;62.2%women;prevalenceofRDR,683/8878fullygradableimages[7.8%]);the

Messidor-2datasethad1748imagesfrom874patients(meanage,57.6years;42.6%women;

prevalenceofRDR,254/1745fullygradableimages[14.6%]).FordetectingRDR,thealgorithm

hadanareaunderthereceiveroperatingcurveof0.991(95%CI,0.988-0.993)forEyePACS-1and

0.990(95%CI,0.986-0.995)forMessidor-2.Usingthefirstoperatingcutpointwithhigh

specificity,forEyePACS-1,thesensitivitywas90.3%(95%CI,87.5%-92.7%)andthespecificity

was98.1%(95%CI,97.8%-98.5%).ForMessidor-2,thesensitivitywas87.0%(95%CI,81.1%-

91.0%)andthespecificitywas98.5%(95%CI,97.7%-99.1%).Usingasecondoperatingpoint

withhighsensitivityinthedevelopmentset,forEyePACS-1thesensitivitywas97.5%and

specificitywas93.4%andforMessidor-2thesensitivitywas96.1%andspecificitywas93.9%.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE In this evaluation of retinal fundus photographs from adults

with diabetes, an algorithm based on deep machine learning had high sensitivity and

specificity for detecting referable diabetic retinopathy. Further research is necessary to

determine the feasibility of applying this algorithm in the clinical setting and to determine

whether use of the algorithm could lead to improved care and outcomes compared with

current ophthalmologic assessment.

JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17216

Published online November 29, 2016.

Editorial

Supplemental content

Author Affiliations: Google Inc,

Mountain View, California (Gulshan,

Peng, Coram, Stumpe, Wu,

Narayanaswamy, Venugopalan,

Widner, Madams, Nelson, Webster);

Department of Computer Science,

University of Texas, Austin

(Venugopalan); EyePACS LLC,

San Jose, California (Cuadros); School

of Optometry, Vision Science

Graduate Group, University of

California, Berkeley (Cuadros);

Aravind Medical Research

Foundation, Aravind Eye Care

System, Madurai, India (Kim); Shri

Bhagwan Mahavir Vitreoretinal

Services, Sankara Nethralaya,

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India (Raman);

Verily Life Sciences, Mountain View,

California (Mega); Cardiovascular

Division, Department of Medicine,

Brigham and Women’s Hospital and

Harvard Medical School, Boston,

Massachusetts (Mega).

Corresponding Author: Lily Peng,

MD, PhD, Google Research, 1600

Amphitheatre Way, Mountain View,

CA 94043 (lhpeng@google.com).

Research

JAMA | Original Investigation | INNOVATIONS IN HEALTH CARE DELIVERY

(Reprinted) E1

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/ on 12/02/2016

ophthalmology

LETTERS

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9

1

Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China. 2

Institute for Genomic Medicine, Institute of

Engineering in Medicine, and Shiley Eye Institute, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA. 3

Hangzhou YITU Healthcare Technology Co. Ltd,

Hangzhou, China. 4

Department of Thoracic Surgery/Oncology, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, China State Key Laboratory and

National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou, China. 5

Guangzhou Kangrui Co. Ltd, Guangzhou, China. 6

Guangzhou Regenerative

Medicine and Health Guangdong Laboratory, Guangzhou, China. 7

Veterans Administration Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, USA. 8

These authors contributed

equally: Huiying Liang, Brian Tsui, Hao Ni, Carolina C. S. Valentim, Sally L. Baxter, Guangjian Liu. *e-mail: kang.zhang@gmail.com; xiahumin@hotmail.com

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods have emerged as

powerful tools to transform medical care. Although machine

learning classifiers (MLCs) have already demonstrated strong

performance in image-based diagnoses, analysis of diverse

and massive electronic health record (EHR) data remains chal-

lenging. Here, we show that MLCs can query EHRs in a manner

similar to the hypothetico-deductive reasoning used by physi-

cians and unearth associations that previous statistical meth-

ods have not found. Our model applies an automated natural

language processing system using deep learning techniques

to extract clinically relevant information from EHRs. In total,

101.6 million data points from 1,362,559 pediatric patient

visits presenting to a major referral center were analyzed to

train and validate the framework. Our model demonstrates

high diagnostic accuracy across multiple organ systems and is

comparable to experienced pediatricians in diagnosing com-

mon childhood diseases. Our study provides a proof of con-

cept for implementing an AI-based system as a means to aid

physicians in tackling large amounts of data, augmenting diag-

nostic evaluations, and to provide clinical decision support in

cases of diagnostic uncertainty or complexity. Although this

impact may be most evident in areas where healthcare provid-

ers are in relative shortage, the benefits of such an AI system

are likely to be universal.

Medical information has become increasingly complex over

time. The range of disease entities, diagnostic testing and biomark-

ers, and treatment modalities has increased exponentially in recent

years. Subsequently, clinical decision-making has also become more

complex and demands the synthesis of decisions from assessment

of large volumes of data representing clinical information. In the

current digital age, the electronic health record (EHR) represents a

massive repository of electronic data points representing a diverse

array of clinical information1–3

. Artificial intelligence (AI) methods

have emerged as potentially powerful tools to mine EHR data to aid

in disease diagnosis and management, mimicking and perhaps even

augmenting the clinical decision-making of human physicians1

.

To formulate a diagnosis for any given patient, physicians fre-

quently use hypotheticodeductive reasoning. Starting with the chief

complaint, the physician then asks appropriately targeted questions

relating to that complaint. From this initial small feature set, the

physician forms a differential diagnosis and decides what features

(historical questions, physical exam findings, laboratory testing,

and/or imaging studies) to obtain next in order to rule in or rule

out the diagnoses in the differential diagnosis set. The most use-

ful features are identified, such that when the probability of one of

the diagnoses reaches a predetermined level of acceptability, the

process is stopped, and the diagnosis is accepted. It may be pos-

sible to achieve an acceptable level of certainty of the diagnosis with

only a few features without having to process the entire feature set.

Therefore, the physician can be considered a classifier of sorts.

In this study, we designed an AI-based system using machine

learning to extract clinically relevant features from EHR notes to

mimic the clinical reasoning of human physicians. In medicine,

machine learning methods have already demonstrated strong per-

formance in image-based diagnoses, notably in radiology2

, derma-

tology4

, and ophthalmology5–8

, but analysis of EHR data presents

a number of difficult challenges. These challenges include the vast

quantity of data, high dimensionality, data sparsity, and deviations

Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric

diseases using artificial intelligence

Huiying Liang1,8

, Brian Y. Tsui 2,8

, Hao Ni3,8

, Carolina C. S. Valentim4,8

, Sally L. Baxter 2,8

,

Guangjian Liu1,8

, Wenjia Cai 2

, Daniel S. Kermany1,2

, Xin Sun1

, Jiancong Chen2

, Liya He1

, Jie Zhu1

,

Pin Tian2

, Hua Shao2

, Lianghong Zheng5,6

, Rui Hou5,6

, Sierra Hewett1,2

, Gen Li1,2

, Ping Liang3

,

Xuan Zang3

, Zhiqi Zhang3

, Liyan Pan1

, Huimin Cai5,6

, Rujuan Ling1

, Shuhua Li1

, Yongwang Cui1

,

Shusheng Tang1

, Hong Ye1

, Xiaoyan Huang1

, Waner He1

, Wenqing Liang1

, Qing Zhang1

, Jianmin Jiang1

,

Wei Yu1

, Jianqun Gao1

, Wanxing Ou1

, Yingmin Deng1

, Qiaozhen Hou1

, Bei Wang1

, Cuichan Yao1

,

Yan Liang1

, Shu Zhang1

, Yaou Duan2

, Runze Zhang2

, Sarah Gibson2

, Charlotte L. Zhang2

, Oulan Li2

,

Edward D. Zhang2

, Gabriel Karin2

, Nathan Nguyen2

, Xiaokang Wu1,2

, Cindy Wen2

, Jie Xu2

, Wenqin Xu2

,

Bochu Wang2

, Winston Wang2

, Jing Li1,2

, Bianca Pizzato2

, Caroline Bao2

, Daoman Xiang1

, Wanting He1,2

,

Suiqin He2

, Yugui Zhou1,2

, Weldon Haw2,7

, Michael Goldbaum2

, Adriana Tremoulet2

, Chun-Nan Hsu 2

,

Hannah Carter2

, Long Zhu3

, Kang Zhang 1,2,7

* and Huimin Xia 1

*

NATURE MEDICINE | www.nature.com/naturemedicine

pediatrics

pathology

1Wang P, et al. Gut 2019;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317500

Endoscopy

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Real-time automatic detection system increases

colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: a

prospective randomised controlled study

Pu Wang, 1

Tyler M Berzin, 2

Jeremy Romek Glissen Brown, 2

Shishira Bharadwaj,2

Aymeric Becq,2

Xun Xiao,1

Peixi Liu,1

Liangping Li,1

Yan Song,1

Di Zhang,1

Yi Li,1

Guangre Xu,1

Mengtian Tu,1

Xiaogang Liu 1

To cite: Wang P, Berzin TM,

Glissen Brown JR, et al. Gut

Epub ahead of print: [please

include Day Month Year].

doi:10.1136/

gutjnl-2018-317500

► Additional material is

published online only.To view

please visit the journal online

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

gutjnl-2018-317500).

1

Department of

Gastroenterology, Sichuan

Academy of Medical Sciences

& Sichuan Provincial People’s

Hospital, Chengdu, China

2

Center for Advanced

Endoscopy, Beth Israel

Deaconess Medical Center and

Harvard Medical School, Boston,

Massachusetts, USA

Correspondence to

Xiaogang Liu, Department

of Gastroenterology Sichuan

Academy of Medical Sciences

and Sichuan Provincial People’s

Hospital, Chengdu, China;

Gary.samsph@gmail.com

Received 30 August 2018

Revised 4 February 2019

Accepted 13 February 2019

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2019. Re-use

permitted under CC BY-NC. No

commercial re-use. See rights

and permissions. Published

by BMJ.

ABSTRACT

Objective The effect of colonoscopy on colorectal

cancer mortality is limited by several factors, among them

a certain miss rate, leading to limited adenoma detection

rates (ADRs).We investigated the effect of an automatic

polyp detection system based on deep learning on polyp

detection rate and ADR.

Design In an open, non-blinded trial, consecutive

patients were prospectively randomised to undergo

diagnostic colonoscopy with or without assistance of a

real-time automatic polyp detection system providing

a simultaneous visual notice and sound alarm on polyp

detection.The primary outcome was ADR.

Results Of 1058 patients included, 536 were

randomised to standard colonoscopy, and 522 were

randomised to colonoscopy with computer-aided

diagnosis.The artificial intelligence (AI) system

significantly increased ADR (29.1%vs20.3%, p<0.001)

and the mean number of adenomas per patient

(0.53vs0.31, p<0.001).This was due to a higher number

of diminutive adenomas found (185vs102; p<0.001),

while there was no statistical difference in larger

adenomas (77vs58, p=0.075). In addition, the number

of hyperplastic polyps was also significantly increased

(114vs52, p<0.001).

Conclusions In a low prevalent ADR population, an

automatic polyp detection system during colonoscopy

resulted in a significant increase in the number of

diminutive adenomas detected, as well as an increase in

the rate of hyperplastic polyps.The cost–benefit ratio of

such effects has to be determined further.

Trial registration number ChiCTR-DDD-17012221;

Results.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second and third-

leading causes of cancer-related deaths in men and

women respectively.1

Colonoscopy is the gold stan-

dard for screening CRC.2 3

Screening colonoscopy

has allowed for a reduction in the incidence and

mortality of CRC via the detection and removal

of adenomatous polyps.4–8

Additionally, there is

evidence that with each 1.0% increase in adenoma

detection rate (ADR), there is an associated 3.0%

decrease in the risk of interval CRC.9 10

However,

polyps can be missed, with reported miss rates of

up to 27% due to both polyp and operator charac-

teristics.11 12

Unrecognised polyps within the visual field is

an important problem to address.11

Several studies

have shown that assistance by a second observer

increases the polyp detection rate (PDR), but such a

strategy remains controversial in terms of increasing

the ADR.13–15

Ideally, a real-time automatic polyp detec-

tion system, with performance close to that of

expert endoscopists, could assist the endosco-

pist in detecting lesions that might correspond to

adenomas in a more consistent and reliable way

Significance of this study

What is already known on this subject?

► Colorectal adenoma detection rate (ADR)

is regarded as a main quality indicator of

(screening) colonoscopy and has been shown

to correlate with interval cancers. Reducing

adenoma miss rates by increasing ADR has

been a goal of many studies focused on

imaging techniques and mechanical methods.

► Artificial intelligence has been recently

introduced for polyp and adenoma detection

as well as differentiation and has shown

promising results in preliminary studies.

What are the new findings?

► This represents the first prospective randomised

controlled trial examining an automatic polyp

detection during colonoscopy and shows an

increase of ADR by 50%, from 20% to 30%.

► This effect was mainly due to a higher rate of

small adenomas found.

► The detection rate of hyperplastic polyps was

also significantly increased.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the

foreseeable future?

► Automatic polyp and adenoma detection could

be the future of diagnostic colonoscopy in order

to achieve stable high adenoma detection rates.

► However, the effect on ultimate outcome is

still unclear, and further improvements such as

polyp differentiation have to be implemented.

on17March2019byguest.Protectedbycopyright.http://gut.bmj.com/Gut:firstpublishedas10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317500on27February2019.Downloadedfrom

pathology

S E P S I S

A targeted real-time early warning score (TREWScore)

for septic shock

Katharine E. Henry,1

David N. Hager,2

Peter J. Pronovost,3,4,5

Suchi Saria1,3,5,6

*

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in the United States, with mortality highest among patients who develop septic

shock. Early aggressive treatment decreases morbidity and mortality. Although automated screening tools can detect

patients currently experiencing severe sepsis and septic shock, none predict those at greatest risk of developing

shock. We analyzed routinely available physiological and laboratory data from intensive care unit patients and devel-

oped “TREWScore,” a targeted real-time early warning score that predicts which patients will develop septic shock.

TREWScore identified patients before the onset of septic shock with an area under the ROC (receiver operating

characteristic) curve (AUC) of 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.81 to 0.85]. At a specificity of 0.67, TREWScore

achieved a sensitivity of 0.85 and identified patients a median of 28.2 [interquartile range (IQR), 10.6 to 94.2] hours

before onset. Of those identified, two-thirds were identified before any sepsis-related organ dysfunction. In compar-

ison, the Modified Early Warning Score, which has been used clinically for septic shock prediction, achieved a lower

AUC of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.76). A routine screening protocol based on the presence of two of the systemic inflam-

matory response syndrome criteria, suspicion of infection, and either hypotension or hyperlactatemia achieved a low-

er sensitivity of 0.74 at a comparable specificity of 0.64. Continuous sampling of data from the electronic health

records and calculation of TREWScore may allow clinicians to identify patients at risk for septic shock and provide

earlier interventions that would prevent or mitigate the associated morbidity and mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Seven hundred fifty thousand patients develop severe sepsis and septic

shock in the United States each year. More than half of them are

admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), accounting for 10% of all

ICU admissions, 20 to 30% of hospital deaths, and $15.4 billion in an-

nual health care costs (1–3). Several studies have demonstrated that

morbidity, mortality, and length of stay are decreased when severe sep-

sis and septic shock are identified and treated early (4–8). In particular,

one study showed that mortality from septic shock increased by 7.6%

with every hour that treatment was delayed after the onset of hypo-

tension (9).

More recent studies comparing protocolized care, usual care, and

early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) for patients with septic shock sug-

gest that usual care is as effective as EGDT (10–12). Some have inter-

preted this to mean that usual care has improved over time and reflects

important aspects of EGDT, such as early antibiotics and early ag-

gressive fluid resuscitation (13). It is likely that continued early identi-

fication and treatment will further improve outcomes. However, the

best approach to managing patients at high risk of developing septic

shock before the onset of severe sepsis or shock has not been studied.

Methods that can identify ahead of time which patients will later expe-

rience septic shock are needed to further understand, study, and im-

prove outcomes in this population.

General-purpose illness severity scoring systems such as the Acute

Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II), Simplified

Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II), SequentialOrgan Failure Assessment

(SOFA) scores, Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), and Simple

Clinical Score (SCS) have been validated to assess illness severity and

risk of death among septic patients (14–17). Although these scores

are useful for predicting general deterioration or mortality, they typical-

ly cannot distinguish with high sensitivity and specificity which patients

are at highest risk of developing a specific acute condition.

The increased use of electronic health records (EHRs), which can be

queried in real time, has generated interest in automating tools that

identify patients at risk for septic shock (18–20). A number of “early

warning systems,” “track and trigger” initiatives, “listening applica-

tions,” and “sniffers” have been implemented to improve detection

andtimelinessof therapy forpatients with severe sepsis andseptic shock

(18, 20–23). Although these tools have been successful at detecting pa-

tients currently experiencing severe sepsis or septic shock, none predict

which patients are at highest risk of developing septic shock.

The adoption of the Affordable Care Act has added to the growing

excitement around predictive models derived from electronic health

data in a variety of applications (24), including discharge planning

(25), risk stratification (26, 27), and identification of acute adverse

events (28, 29). For septic shock in particular, promising work includes

that of predicting septic shock using high-fidelity physiological signals

collected directly from bedside monitors (30, 31), inferring relationships

between predictors of septic shock using Bayesian networks (32), and

using routine measurements for septic shock prediction (33–35). No

current prediction models that use only data routinely stored in the

EHR predict septic shock with high sensitivity and specificity many

hours before onset. Moreover, when learning predictive risk scores, cur-

rent methods (34, 36, 37) often have not accounted for the censoring

effects of clinical interventions on patient outcomes (38). For instance,

a patient with severe sepsis who received fluids and never developed

septic shock would be treated as a negative case, despite the possibility

that he or she might have developed septic shock in the absence of such

treatment and therefore could be considered a positive case up until the

1

Department of Computer Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

2

Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, School of

Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA. 3

Armstrong Institute for

Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21202, USA. 4

Department

of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University,

Baltimore, MD 21202, USA. 5

Department of Health Policy and Management, Bloomberg

School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA. 6

Department

of Applied Math and Statistics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

*Corresponding author. E-mail: ssaria@cs.jhu.edu

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

www.ScienceTranslationalMedicine.org 5 August 2015 Vol 7 Issue 299 299ra122 1

onNovember3,2016http://stm.sciencemag.org/Downloadedfrom

infectious

BRIEF COMMUNICATION OPEN

Digital biomarkers of cognitive function

Paul Dagum1

To identify digital biomarkers associated with cognitive function, we analyzed human–computer interaction from 7 days of

smartphone use in 27 subjects (ages 18–34) who received a gold standard neuropsychological assessment. For several

neuropsychological constructs (working memory, memory, executive function, language, and intelligence), we found a family of

digital biomarkers that predicted test scores with high correlations (p < 10−4

). These preliminary results suggest that passive

measures from smartphone use could be a continuous ecological surrogate for laboratory-based neuropsychological assessment.

npj Digital Medicine (2018)1:10 ; doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0018-4

INTRODUCTION

By comparison to the functional metrics available in other

disciplines, conventional measures of neuropsychiatric disorders

have several challenges. First, they are obtrusive, requiring a

subject to break from their normal routine, dedicating time and

often travel. Second, they are not ecological and require subjects

to perform a task outside of the context of everyday behavior.

Third, they are episodic and provide sparse snapshots of a patient

only at the time of the assessment. Lastly, they are poorly scalable,

taxing limited resources including space and trained staff.

In seeking objective and ecological measures of cognition, we

attempted to develop a method to measure memory and

executive function not in the laboratory but in the moment,

day-to-day. We used human–computer interaction on smart-

phones to identify digital biomarkers that were correlated with

neuropsychological performance.

RESULTS

In 2014, 27 participants (ages 27.1 ± 4.4 years, education

14.1 ± 2.3 years, M:F 8:19) volunteered for neuropsychological

assessment and a test of the smartphone app. Smartphone

human–computer interaction data from the 7 days following

the neuropsychological assessment showed a range of correla-

tions with the cognitive scores. Table 1 shows the correlation

between each neurocognitive test and the cross-validated

predictions of the supervised kernel PCA constructed from

the biomarkers for that test. Figure 1 shows each participant

test score and the digital biomarker prediction for (a) digits

backward, (b) symbol digit modality, (c) animal fluency,

(d) Wechsler Memory Scale-3rd Edition (WMS-III) logical

memory (delayed free recall), (e) brief visuospatial memory test

(delayed free recall), and (f) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-

4th Edition (WAIS-IV) block design. Construct validity of the

predictions was determined using pattern matching that

computed a correlation of 0.87 with p < 10−59

between the

covariance matrix of the predictions and the covariance matrix

of the tests.

Table 1. Fourteen neurocognitive assessments covering five cognitive

domains and dexterity were performed by a neuropsychologist.

Shown are the group mean and standard deviation, range of score,

and the correlation between each test and the cross-validated

prediction constructed from the digital biomarkers for that test

Cognitive predictions

Mean (SD) Range R (predicted),

p-value

Working memory

Digits forward 10.9 (2.7) 7–15 0.71 ± 0.10, 10−4

Digits backward 8.3 (2.7) 4–14 0.75 ± 0.08, 10−5

Executive function

Trail A 23.0 (7.6) 12–39 0.70 ± 0.10, 10−4

Trail B 53.3 (13.1) 37–88 0.82 ± 0.06, 10−6

Symbol digit modality 55.8 (7.7) 43–67 0.70 ± 0.10, 10−4

Language

Animal fluency 22.5 (3.8) 15–30 0.67 ± 0.11, 10−4

FAS phonemic fluency 42 (7.1) 27–52 0.63 ± 0.12, 10−3

Dexterity

Grooved pegboard test

(dominant hand)

62.7 (6.7) 51–75 0.73 ± 0.09, 10−4

Memory

California verbal learning test

(delayed free recall)

14.1 (1.9) 9–16 0.62 ± 0.12, 10−3

WMS-III logical memory

(delayed free recall)

29.4 (6.2) 18–42 0.81 ± 0.07, 10−6

Brief visuospatial memory test

(delayed free recall)

10.2 (1.8) 5–12 0.77 ± 0.08, 10−5

Intelligence scale

WAIS-IV block design 46.1(12.8) 12–61 0.83 ± 0.06, 10−6

WAIS-IV matrix reasoning 22.1(3.3) 12–26 0.80 ± 0.07, 10−6

WAIS-IV vocabulary 40.6(4.0) 31–50 0.67 ± 0.11, 10−4

Received: 5 October 2017 Revised: 3 February 2018 Accepted: 7 February 2018

1

Mindstrong Health, 248 Homer Street, Palo Alto, CA 94301, USA

Correspondence: Paul Dagum (paul@mindstronghealth.com)

www.nature.com/npjdigitalmed

psychiatry

P R E C I S I O N M E D I C I N E

Identification of type 2 diabetes subgroups through

topological analysis of patient similarity

Li Li,1

Wei-Yi Cheng,1

Benjamin S. Glicksberg,1

Omri Gottesman,2

Ronald Tamler,3

Rong Chen,1

Erwin P. Bottinger,2

Joel T. Dudley1,4

*

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a heterogeneous complex disease affecting more than 29 million Americans alone with a

rising prevalence trending toward steady increases in the coming decades. Thus, there is a pressing clinical need to

improve early prevention and clinical management of T2D and its complications. Clinicians have understood that

patients who carry the T2D diagnosis have a variety of phenotypes and susceptibilities to diabetes-related compli-

cations. We used a precision medicine approach to characterize the complexity of T2D patient populations based

on high-dimensional electronic medical records (EMRs) and genotype data from 11,210 individuals. We successfully

identified three distinct subgroups of T2D from topology-based patient-patient networks. Subtype 1 was character-

ized by T2D complications diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy; subtype 2 was enriched for cancer ma-

lignancy and cardiovascular diseases; and subtype 3 was associated most strongly with cardiovascular diseases,

neurological diseases, allergies, and HIV infections. We performed a genetic association analysis of the emergent

T2D subtypes to identify subtype-specific genetic markers and identified 1279, 1227, and 1338 single-nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs) that mapped to 425, 322, and 437 unique genes specific to subtypes 1, 2, and 3, respec-

tively. By assessing the human disease–SNP association for each subtype, the enriched phenotypes and

biological functions at the gene level for each subtype matched with the disease comorbidities and clinical dif-

ferences that we identified through EMRs. Our approach demonstrates the utility of applying the precision

medicine paradigm in T2D and the promise of extending the approach to the study of other complex, multi-

factorial diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a complex, multifactorial disease that has

emerged as an increasing prevalent worldwide health concern asso-

ciated with high economic and physiological burdens. An estimated

29.1 million Americans (9.3% of the population) were estimated to

have some form of diabetes in 2012—up 13% from 2010—with T2D

representing up to 95% of all diagnosed cases (1, 2). Risk factors for

T2D include obesity, family history of diabetes, physical inactivity, eth-

nicity, and advanced age (1, 2). Diabetes and its complications now

rank among the leading causes of death in the United States (2). In fact,

diabetes is the leading cause of nontraumatic foot amputation, adult

blindness, and need for kidney dialysis, and multiplies risk for myo-

cardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease

(3–6). The total estimated direct medical cost attributable to diabetes in

the United States in 2012 was $176 billion, with an estimated $76 billion

attributable to hospital inpatient care alone. There is a great need to im-

prove understanding of T2D and its complex factors to facilitate pre-

vention, early detection, and improvements in clinical management.

A more precise characterization of T2D patient populations can en-

hance our understanding of T2D pathophysiology (7, 8). Current

clinical definitions classify diabetes into three major subtypes: type 1 dia-

betes (T1D), T2D, and maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Other sub-

types based on phenotype bridge the gap between T1D and T2D, for

example, latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) (7) and ketosis-

prone T2D. The current categories indicate that the traditional definition of

diabetes, especially T2D, might comprise additional subtypes with dis-

tinct clinical characteristics. A recent analysis of the longitudinal Whitehall

II cohort study demonstrated improved assessment of cardiovascular

risks when subgrouping T2D patients according to glucose concentration

criteria (9). Genetic association studies reveal that the genetic architec-

ture of T2D is profoundly complex (10–12). Identified T2D-associated

risk variants exhibit allelic heterogeneity and directional differentiation

among populations (13, 14). The apparent clinical and genetic com-

plexity and heterogeneity of T2D patient populations suggest that there

are opportunities to refine the current, predominantly symptom-based,

definition of T2D into additional subtypes (7).

Because etiological and pathophysiological differences exist among

T2D patients, we hypothesize that a data-driven analysis of a clinical

population could identify new T2D subtypes and factors. Here, we de-

velop a data-driven, topology-based approach to (i) map the complexity

of patient populations using clinical data from electronic medical re-

cords (EMRs) and (ii) identify new, emergent T2D patient subgroups

with subtype-specific clinical and genetic characteristics. We apply this

approachtoadatasetcomprisingmatchedEMRsandgenotypedatafrom

more than 11,000 individuals. Topological analysis of these data revealed

three distinct T2D subtypes that exhibited distinct patterns of clinical

characteristics and disease comorbidities. Further, we identified genetic

markers associated with each T2D subtype and performed gene- and

pathway-level analysis of subtype genetic associations. Biological and

phenotypic features enriched in the genetic analysis corroborated clinical

disparities observed among subgroups. Our findings suggest that data-

driven,topologicalanalysisofpatientcohortshasutilityinprecisionmedicine

effortstorefineourunderstandingofT2Dtowardimproving patient care.

1

Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount

Sinai, 700 Lexington Ave., New York, NY 10065, USA. 2

Institute for Personalized Medicine,

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029,

USA. 3

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Bone Diseases, Icahn School of Medicine

at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA. 4

Department of Health Policy and Research,

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA.

*Corresponding author. E-mail: joel.dudley@mssm.edu

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

www.ScienceTranslationalMedicine.org 28 October 2015 Vol 7 Issue 311 311ra174 1

onOctober28,2015http://stm.sciencemag.org/Downloadedfrom

endocrinology

0 0 M O N T H 2 0 1 7 | V O L 0 0 0 | N A T U R E | 1

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature21056

Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer

with deep neural networks

Andre Esteva1

*, Brett Kuprel1

*, Roberto A. Novoa2,3

, Justin Ko2

, Susan M. Swetter2,4

, Helen M. Blau5

& Sebastian Thrun6

Skin cancer, the most common human malignancy1–3

, is primarily

diagnosed visually, beginning with an initial clinical screening

and followed potentially by dermoscopic analysis, a biopsy and

histopathological examination. Automated classification of skin

lesions using images is a challenging task owing to the fine-grained

variability in the appearance of skin lesions. Deep convolutional

neural networks (CNNs)4,5

show potential for general and highly

variable tasks across many fine-grained object categories6–11

.

Here we demonstrate classification of skin lesions using a single

CNN, trained end-to-end from images directly, using only pixels

and disease labels as inputs. We train a CNN using a dataset of

129,450 clinical images—two orders of magnitude larger than

previous datasets12

—consisting of 2,032 different diseases. We

test its performance against 21 board-certified dermatologists on

biopsy-proven clinical images with two critical binary classification

use cases: keratinocyte carcinomas versus benign seborrheic

keratoses; and malignant melanomas versus benign nevi. The first

case represents the identification of the most common cancers, the

second represents the identification of the deadliest skin cancer.

The CNN achieves performance on par with all tested experts

across both tasks, demonstrating an artificial intelligence capable

of classifying skin cancer with a level of competence comparable to

dermatologists. Outfitted with deep neural networks, mobile devices

can potentially extend the reach of dermatologists outside of the

clinic. It is projected that 6.3 billion smartphone subscriptions will

exist by the year 2021 (ref. 13) and can therefore potentially provide

low-cost universal access to vital diagnostic care.

There are 5.4 million new cases of skin cancer in the United States2

every year. One in five Americans will be diagnosed with a cutaneous

malignancy in their lifetime. Although melanomas represent fewer than

5% of all skin cancers in the United States, they account for approxi-

mately 75% of all skin-cancer-related deaths, and are responsible for

over 10,000 deaths annually in the United States alone. Early detection

is critical, as the estimated 5-year survival rate for melanoma drops

from over 99% if detected in its earliest stages to about 14% if detected

in its latest stages. We developed a computational method which may

allow medical practitioners and patients to proactively track skin

lesions and detect cancer earlier. By creating a novel disease taxonomy,

and a disease-partitioning algorithm that maps individual diseases into

training classes, we are able to build a deep learning system for auto-

mated dermatology.

Previous work in dermatological computer-aided classification12,14,15

has lacked the generalization capability of medical practitioners

owing to insufficient data and a focus on standardized tasks such as

dermoscopy16–18

and histological image classification19–22

. Dermoscopy

images are acquired via a specialized instrument and histological

images are acquired via invasive biopsy and microscopy; whereby

both modalities yield highly standardized images. Photographic

images (for example, smartphone images) exhibit variability in factors

such as zoom, angle and lighting, making classification substantially

more challenging23,24

. We overcome this challenge by using a data-

driven approach—1.41 million pre-training and training images

make classification robust to photographic variability. Many previous

techniques require extensive preprocessing, lesion segmentation and

extraction of domain-specific visual features before classification. By

contrast, our system requires no hand-crafted features; it is trained

end-to-end directly from image labels and raw pixels, with a single

network for both photographic and dermoscopic images. The existing

body of work uses small datasets of typically less than a thousand

images of skin lesions16,18,19

, which, as a result, do not generalize well

to new images. We demonstrate generalizable classification with a new

dermatologist-labelled dataset of 129,450 clinical images, including

3,374 dermoscopy images.

Deep learning algorithms, powered by advances in computation

and very large datasets25

, have recently been shown to exceed human

performance in visual tasks such as playing Atari games26

, strategic

board games like Go27

and object recognition6

. In this paper we

outline the development of a CNN that matches the performance of

dermatologists at three key diagnostic tasks: melanoma classification,

melanoma classification using dermoscopy and carcinoma

classification. We restrict the comparisons to image-based classification.

We utilize a GoogleNet Inception v3 CNN architecture9

that was pre-

trained on approximately 1.28 million images (1,000 object categories)

from the 2014 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge6

,

and train it on our dataset using transfer learning28

. Figure 1 shows the

working system. The CNN is trained using 757 disease classes. Our

dataset is composed of dermatologist-labelled images organized in a

tree-structured taxonomy of 2,032 diseases, in which the individual

diseases form the leaf nodes. The images come from 18 different

clinician-curated, open-access online repositories, as well as from

clinical data from Stanford University Medical Center. Figure 2a shows

a subset of the full taxonomy, which has been organized clinically and

visually by medical experts. We split our dataset into 127,463 training

and validation images and 1,942 biopsy-labelled test images.

To take advantage of fine-grained information contained within the

taxonomy structure, we develop an algorithm (Extended Data Table 1)

to partition diseases into fine-grained training classes (for example,

amelanotic melanoma and acrolentiginous melanoma). During

inference, the CNN outputs a probability distribution over these fine

classes. To recover the probabilities for coarser-level classes of interest

(for example, melanoma) we sum the probabilities of their descendants

(see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1 for more details).

We validate the effectiveness of the algorithm in two ways, using

nine-fold cr

dermatology

FOCUS LETTERS

W

W

W

Ca d o og s eve a hy hm a de ec on and

c ass ca on n ambu a o y e ec oca d og ams

us ng a deep neu a ne wo k

M m

M

FOCUS LETTERS

D p a n ng nab obu a m n and on o

human b a o y a n v o a on

gynecology

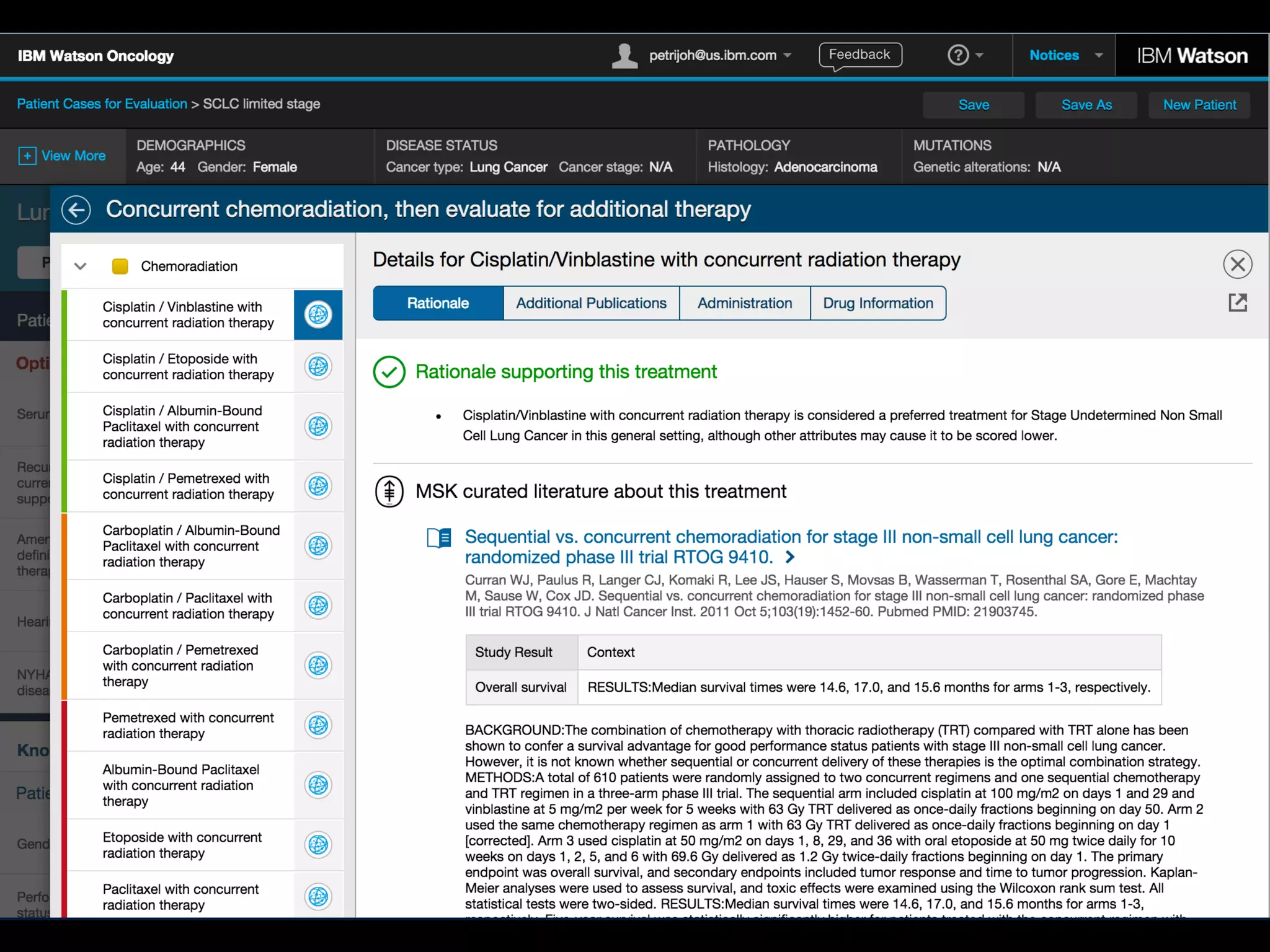

O G NA A

W on o On o og nd b e n e e men

e ommend on g eemen w h n e pe

mu d p n umo bo d

oncology

D m

m

B D m OHCA

m Kw MD K H MD M H M K m MD

M M K m MD M M L m MD M K H K m

MD D MD D MD D R K C

MD D B H O MD D

D m Em M M H

K

D C C C M H

K

T w

A D C D m

M C C M H

G m w G R K

Tw w

C A K H MD D C

D m M C C M

H K G m w G

R K T E m

m @ m m

A

A m O OHCA m

m m w w

T m

m DCA

M T w m K OHCA w

A

CCEPTED

M

A

N

U

SCRIPT

emergency med

nephrology

gastroenterology

ThTh

C

% %

% %

Deve opmen and Va da on o Deep

Lea n ng–based Au oma c De ec on

A go hm o Ma gnan Pu mona y Nodu es

on Ches Rad og aphs

M M M M

M Th M M

M M M M

Th

radiology cardiology

LETTERS

W

Au oma ed deep neu a ne wo k su ve ance o

c an a mages o acu e neu o og c even s

M M M

m M

m m

neurology](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asgo2019medicalai191010-191010155811/75/ASGO-2019-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Medicine-5-2048.jpg)

![ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Watson for Oncology and breast cancer treatment

recommendations: agreement with an expert

multidisciplinary tumor board

S. P. Somashekhar1*, M.-J. Sepu´lveda2

, S. Puglielli3

, A. D. Norden3

, E. H. Shortliffe4

, C. Rohit Kumar1

,

A. Rauthan1

, N. Arun Kumar1

, P. Patil1

, K. Rhee3

& Y. Ramya1

1

Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Centre, Manipal Hospital, Bangalore, India; 2

IBM Research (Retired), Yorktown Heights; 3

Watson Health, IBM Corporation,

Cambridge; 4

Department of Surgical Oncology, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, USA

*Correspondence to: Prof. Sampige Prasannakumar Somashekhar, Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Centre, Manipal Hospital, Old Airport Road, Bangalore 560017, Karnataka,

India. Tel: þ91-9845712012; Fax: þ91-80-2502-3759; E-mail: somashekhar.sp@manipalhospitals.com

Background: Breast cancer oncologists are challenged to personalize care with rapidly changing scientific evidence, drug

approvals, and treatment guidelines. Artificial intelligence (AI) clinical decision-support systems (CDSSs) have the potential to

help address this challenge. We report here the results of examining the level of agreement (concordance) between treatment

recommendations made by the AI CDSS Watson for Oncology (WFO) and a multidisciplinary tumor board for breast cancer.

Patients and methods: Treatment recommendations were provided for 638 breast cancers between 2014 and 2016 at the

Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Center, Bengaluru, India. WFO provided treatment recommendations for the identical cases in

2016. A blinded second review was carried out by the center’s tumor board in 2016 for all cases in which there was not

agreement, to account for treatments and guidelines not available before 2016. Treatment recommendations were considered

concordant if the tumor board recommendations were designated ‘recommended’ or ‘for consideration’ by WFO.

Results: Treatment concordance between WFO and the multidisciplinary tumor board occurred in 93% of breast cancer cases.

Subgroup analysis found that patients with stage I or IV disease were less likely to be concordant than patients with stage II or III

disease. Increasing age was found to have a major impact on concordance. Concordance declined significantly (P 0.02;

P < 0.001) in all age groups compared with patients <45 years of age, except for the age group 55–64 years. Receptor status

was not found to affect concordance.

Conclusion: Treatment recommendations made by WFO and the tumor board were highly concordant for breast cancer cases

examined. Breast cancer stage and patient age had significant influence on concordance, while receptor status alone did not.

This study demonstrates that the AI clinical decision-support system WFO may be a helpful tool for breast cancer treatment

decision making, especially at centers where expert breast cancer resources are limited.

Key words: Watson for Oncology, artificial intelligence, cognitive clinical decision-support systems, breast cancer,

concordance, multidisciplinary tumor board

Introduction

Oncologists who treat breast cancer are challenged by a large and

rapidly expanding knowledge base [1, 2]. As of October 2017, for

example, there were 69 FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of

breast cancer, not including combination treatment regimens

[3]. The growth of massive genetic and clinical databases, along

with computing systems to exploit them, will accelerate the speed

of breast cancer treatment advances and shorten the cycle time

for changes to breast cancer treatment guidelines [4, 5]. In add-

ition, these information management challenges in cancer care

are occurring in a practice environment where there is little time

available for tracking and accessing relevant information at the

point of care [6]. For example, a study that surveyed 1117 oncolo-

gists reported that on average 4.6 h per week were spent keeping

VC The Author(s) 2018. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com.

Annals of Oncology 29: 418–423, 2018

doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx781

Published online 9 January 2018

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article-abstract/29/2/418/4781689

by guest

•Annals of Oncology, 2018 January

•Concordance between WFO and MTB for breast cancer treatment plan

•The first and the only paper, which published in peer-reviewed journal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asgo2019medicalai191010-191010155811/75/ASGO-2019-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Medicine-26-2048.jpg)

![This copy is for personal use only.

To order printed copies, contact reprints@rsna.org

This copy is for personal use only.

To order printed copies, contact reprints@rsna.org

ORIGINAL RESEARCH • THORACIC IMAGING

hest radiography, one of the most common diagnos- intraobserver agreements because of its limited spatial reso-

Development and Validation of Deep

Learning–based Automatic Detection

Algorithm for Malignant Pulmonary Nodules

on Chest Radiographs

Ju Gang Nam, MD* • Sunggyun Park, PhD* • Eui Jin Hwang, MD • Jong Hyuk Lee, MD • Kwang-Nam Jin, MD,

PhD • KunYoung Lim, MD, PhD • Thienkai HuyVu, MD, PhD • Jae Ho Sohn, MD • Sangheum Hwang, PhD • Jin

Mo Goo, MD, PhD • Chang Min Park, MD, PhD

From the Department of Radiology and Institute of Radiation Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital and College of Medicine, 101 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul

03080, Republic of Korea (J.G.N., E.J.H., J.M.G., C.M.P.); Lunit Incorporated, Seoul, Republic of Korea (S.P.); Department of Radiology, Armed Forces Seoul Hospital,

Seoul, Republic of Korea (J.H.L.); Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea (K.N.J.); Department of

Radiology, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Republic of Korea (K.Y.L.); Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco,

San Francisco, Calif (T.H.V., J.H.S.); and Department of Industrial & Information Systems Engineering, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul,

Republic of Korea (S.H.). Received January 30, 2018; revision requested March 20; revision received July 29; accepted August 6. Address correspondence to C.M.P.

(e-mail: cmpark.morphius@gmail.com).

Study supported by SNUH Research Fund and Lunit (06–2016–3000) and by Seoul Research and Business Development Program (FI170002).

*J.G.N. and S.P. contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

Radiology 2018; 00:1–11 • https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018180237 • Content codes:

Purpose: To develop and validate a deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm (DLAD) for malignant pulmonary nodules

on chest radiographs and to compare its performance with physicians including thoracic radiologists.

Materials and Methods: For this retrospective study, DLAD was developed by using 43292 chest radiographs (normal radiograph–

to–nodule radiograph ratio, 34067:9225) in 34676 patients (healthy-to-nodule ratio, 30784:3892; 19230 men [mean age, 52.8

years; age range, 18–99 years]; 15446 women [mean age, 52.3 years; age range, 18–98 years]) obtained between 2010 and 2015,

which were labeled and partially annotated by 13 board-certified radiologists, in a convolutional neural network. Radiograph clas-

sification and nodule detection performances of DLAD were validated by using one internal and four external data sets from three

South Korean hospitals and one U.S. hospital. For internal and external validation, radiograph classification and nodule detection

performances of DLAD were evaluated by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and jackknife

alternative free-response receiver-operating characteristic (JAFROC) figure of merit (FOM), respectively. An observer performance

test involving 18 physicians, including nine board-certified radiologists, was conducted by using one of the four external validation

data sets. Performances of DLAD, physicians, and physicians assisted with DLAD were evaluated and compared.

Results: According to one internal and four external validation data sets, radiograph classification and nodule detection perfor-

mances of DLAD were a range of 0.92–0.99 (AUROC) and 0.831–0.924 (JAFROC FOM), respectively. DLAD showed a higher

AUROC and JAFROC FOM at the observer performance test than 17 of 18 and 15 of 18 physicians, respectively (P , .05), and

all physicians showed improved nodule detection performances with DLAD (mean JAFROC FOM improvement, 0.043; range,

0.006–0.190; P , .05).

Conclusion: This deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm outperformed physicians in radiograph classification and nod-

ule detection performance for malignant pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs, and it enhanced physicians’ performances when

used as a second reader.

©RSNA, 2018

Online supplemental material is available for this article.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asgo2019medicalai191010-191010155811/75/ASGO-2019-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Medicine-47-2048.jpg)

![This copy is for personal use only.

To order printed copies, contact reprints@rsna.org

This copy is for personal use only.

To order printed copies, contact reprints@rsna.org

ORIGINAL RESEARCH • THORACIC IMAGING

hest radiography, one of the most common diagnos- intraobserver agreements because of its limited spatial reso-

Development and Validation of Deep

Learning–based Automatic Detection

Algorithm for Malignant Pulmonary Nodules

on Chest Radiographs

Ju Gang Nam, MD* • Sunggyun Park, PhD* • Eui Jin Hwang, MD • Jong Hyuk Lee, MD • Kwang-Nam Jin, MD,

PhD • KunYoung Lim, MD, PhD • Thienkai HuyVu, MD, PhD • Jae Ho Sohn, MD • Sangheum Hwang, PhD • Jin

Mo Goo, MD, PhD • Chang Min Park, MD, PhD

From the Department of Radiology and Institute of Radiation Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital and College of Medicine, 101 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul

03080, Republic of Korea (J.G.N., E.J.H., J.M.G., C.M.P.); Lunit Incorporated, Seoul, Republic of Korea (S.P.); Department of Radiology, Armed Forces Seoul Hospital,

Seoul, Republic of Korea (J.H.L.); Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea (K.N.J.); Department of

Radiology, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Republic of Korea (K.Y.L.); Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco,

San Francisco, Calif (T.H.V., J.H.S.); and Department of Industrial & Information Systems Engineering, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul,

Republic of Korea (S.H.). Received January 30, 2018; revision requested March 20; revision received July 29; accepted August 6. Address correspondence to C.M.P.

(e-mail: cmpark.morphius@gmail.com).

Study supported by SNUH Research Fund and Lunit (06–2016–3000) and by Seoul Research and Business Development Program (FI170002).

*J.G.N. and S.P. contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

Radiology 2018; 00:1–11 • https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018180237 • Content codes:

Purpose: To develop and validate a deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm (DLAD) for malignant pulmonary nodules

on chest radiographs and to compare its performance with physicians including thoracic radiologists.

Materials and Methods: For this retrospective study, DLAD was developed by using 43292 chest radiographs (normal radiograph–

to–nodule radiograph ratio, 34067:9225) in 34676 patients (healthy-to-nodule ratio, 30784:3892; 19230 men [mean age, 52.8

years; age range, 18–99 years]; 15446 women [mean age, 52.3 years; age range, 18–98 years]) obtained between 2010 and 2015,

which were labeled and partially annotated by 13 board-certified radiologists, in a convolutional neural network. Radiograph clas-

sification and nodule detection performances of DLAD were validated by using one internal and four external data sets from three

South Korean hospitals and one U.S. hospital. For internal and external validation, radiograph classification and nodule detection

performances of DLAD were evaluated by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and jackknife

alternative free-response receiver-operating characteristic (JAFROC) figure of merit (FOM), respectively. An observer performance

test involving 18 physicians, including nine board-certified radiologists, was conducted by using one of the four external validation

data sets. Performances of DLAD, physicians, and physicians assisted with DLAD were evaluated and compared.

Results: According to one internal and four external validation data sets, radiograph classification and nodule detection perfor-

mances of DLAD were a range of 0.92–0.99 (AUROC) and 0.831–0.924 (JAFROC FOM), respectively. DLAD showed a higher

AUROC and JAFROC FOM at the observer performance test than 17 of 18 and 15 of 18 physicians, respectively (P , .05), and

all physicians showed improved nodule detection performances with DLAD (mean JAFROC FOM improvement, 0.043; range,

0.006–0.190; P , .05).

Conclusion: This deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm outperformed physicians in radiograph classification and nod-

ule detection performance for malignant pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs, and it enhanced physicians’ performances when

used as a second reader.

©RSNA, 2018

Online supplemental material is available for this article.

• 43,292 chest PA (normal:nodule=34,067:9225)

• labeled/annotated by 13 board-certified radiologists.

• DLAD were validated 1 internal + 4 external datasets

• Classification / Lesion localization

• AI vs. Physician vs. Physician+AI

• Compared various level of physicians

• Non-radiology / radiology residents

• Board-certified radiologist / Thoracic radiologists](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asgo2019medicalai191010-191010155811/75/ASGO-2019-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Medicine-48-2048.jpg)

![ORIGINAL RESEARCH BREAST IMAGING

S

ince the creation of the Gail model in 1989 (1), risk

models have supported risk-adjusted screening and pre-

vention and their continued evolution has been a central

pillar of breast cancer research (1–8). Previous research

(2,3) explored multiple risk factors related to hormonal

and genetic information. Mammographic breast density,

which relates to the amount of fibroglandular tissue in a

woman’s breast, is a risk factor that received substantial at-

tention. Brentnall et al (8) incorporated mammographic

breast density into the Gail risk model and Tyrer-Cuzick

model (TC), improving their areas under the receiver op-

erating characteristic curve (AUCs) from 0.55 and 0.57 to

0.59 and 0.61, respectively.

The use of breast density as a proxy for the detailed in-

mammography with vastly different outcomes. Whereas

previous studies (10–12) explored automated methods to

assess breast density, these efforts reduced the mammo-

graphic input into a few statistics largely related to volume

of glandular tissue that are not sufficient to distinguish pa-

tients who will and will not develop breast cancer.

We hypothesize that there are subtle but informa-

tive cues on mammograms that may not be discernible

by humans or simple volume-of-density measurements,

and deep learning (DL) can leverage these cues to yield

improved risk models. Therefore, we developed a DL

model that operates over a full-field mammographic im-

age to assess a patient’s future breast cancer risk. Rather

than manually identifying discriminative image patterns,

A Deep Learning Mammography-based Model for

Improved Breast Cancer Risk Prediction

From the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 32 Vassar St, 32-G484, Cambridge, MA 02139 (A.Y.,

T.S., T.P., R.B.); and Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass (C.L.). Received November 28, 2018; revision

requested January 18, 2019; revision received March 14; accepted March 18. Address correspondence to A.Y. (e-mail: adamyala@csail.mit.edu).