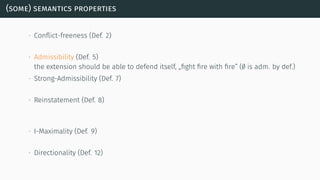

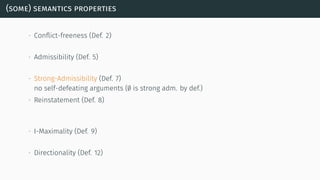

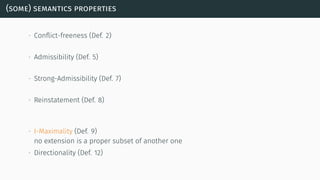

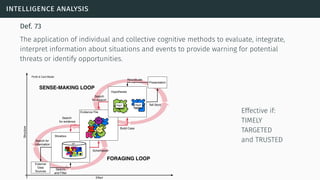

The document discusses the evolution of argumentation in artificial intelligence, reflecting on twenty years since Dung's foundational framework. It explores various argumentation schemes, semantics, and algorithms, addressing the theoretical and practical aspects of argumentative reasoning. Additionally, it touches on applications in multi-agent systems and the complexity of different argumentation semantics.

![[Dun95]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-20-320.jpg)

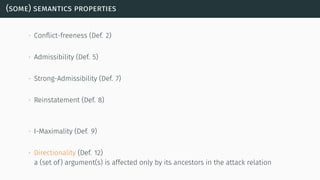

![(some) semantics properties

[BG07] [BCG11]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-23-320.jpg)

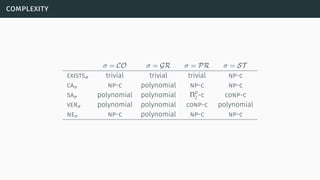

![complexity

[DW09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-42-320.jpg)

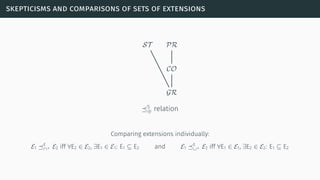

![skepticisms and comparisons of sets of extensions

[BG09b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-50-320.jpg)

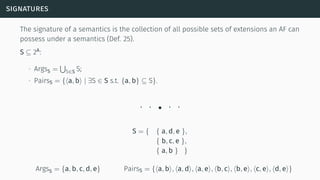

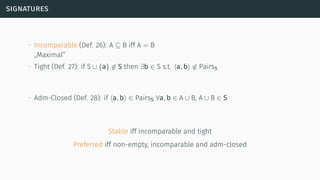

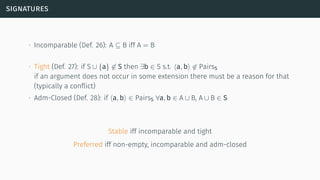

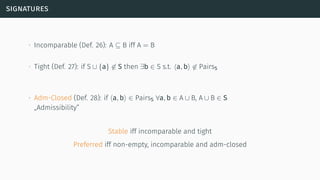

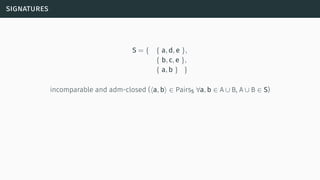

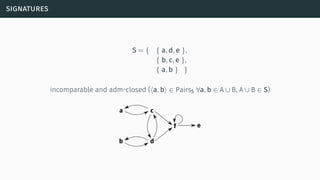

![signatures

[Dun+14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-52-320.jpg)

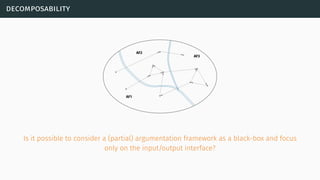

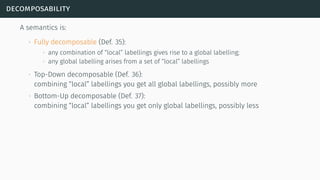

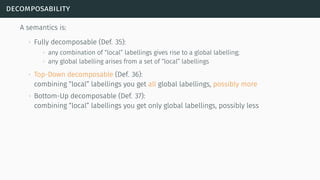

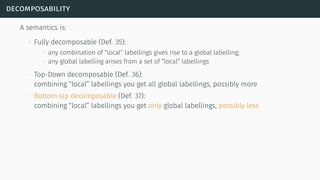

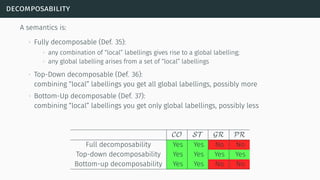

![decomposability

[Bar+14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-61-320.jpg)

![[WRM08]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-70-320.jpg)

![[Rah+11]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-76-320.jpg)

![[Bex+13]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-79-320.jpg)

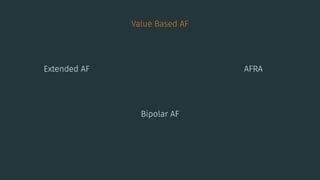

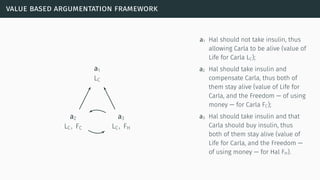

![value based argumentation framework

[BA09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-84-320.jpg)

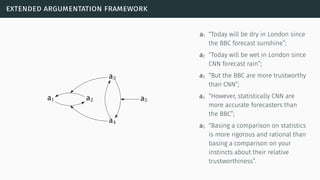

![extended argumentation framework

[Mod09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-87-320.jpg)

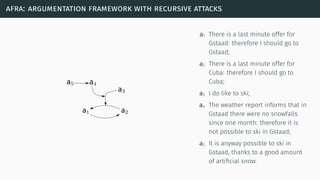

![afra: argumentation framework with recursive attacks

[Bar+11]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-90-320.jpg)

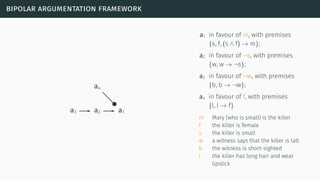

![bipolar argumentation framework

[CL05]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-93-320.jpg)

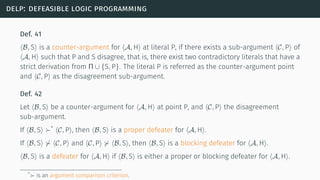

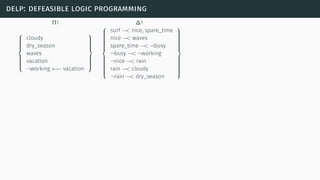

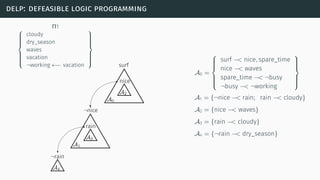

![delp: defeasible logic programming

[SL92] [GS14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-97-320.jpg)

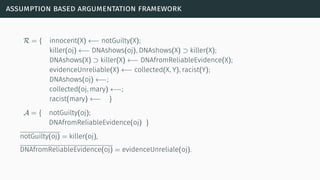

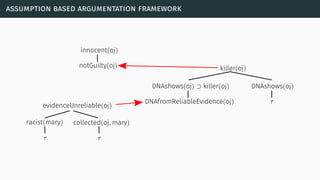

![assumption based argumentation framework

[Bon+97] [Ton14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-103-320.jpg)

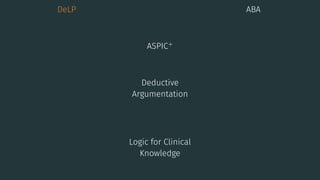

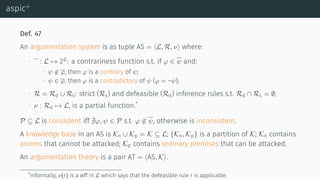

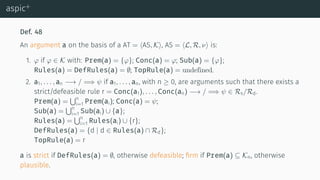

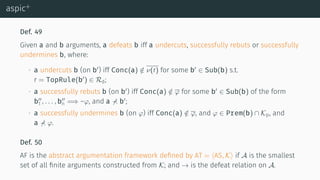

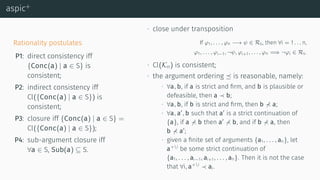

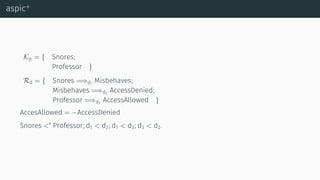

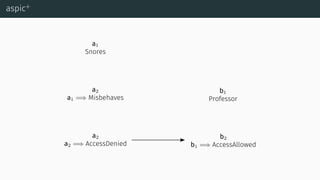

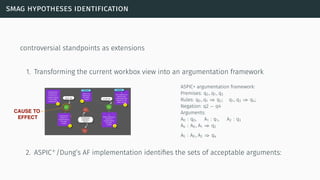

![aspic+

[Pra10] [MP13] [MP14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-108-320.jpg)

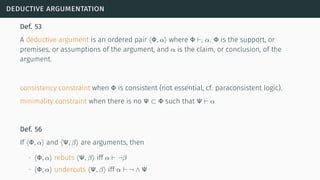

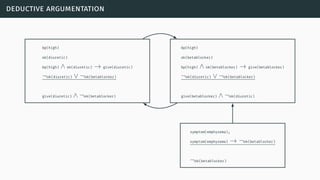

![deductive argumentation

[BH01] [GH11] [BH14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-117-320.jpg)

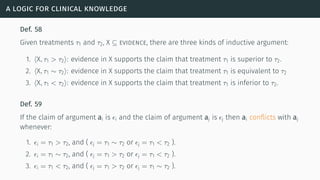

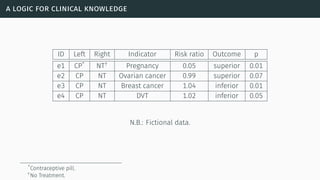

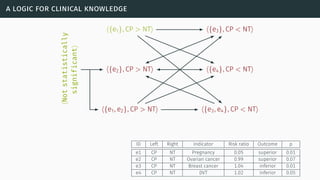

![a logic for clinical knowledge

[HW12] [Wil+15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-122-320.jpg)

![a logic for clinical knowledge

Def. 60

For any pair of arguments ai and aj, and a preference relation R, ai attacks aj with respect

to R iff ai conflicts with aj and it is not the case that aj is strictly preferred to ai according

to R.

A domain-specific benefit preference relation is defined in [HW12]

Def. 61 (Meta arguments)

For a ∈ Arg(evidence), if there is an e ∈ support(a) such that:

∙ e is not statistically significant, and e is not a side-effect, then this is an attacker:

⟨Not statistically significant⟩;

∙ e is a non-randomised and non-blind trial, then this is an attacker:

⟨Non-randomized & non-blind trials⟩;

∙ e is a meta-analysis that concerns a narrow patient group, then this is an attacker:

⟨Meta-analysis for a narrow patient group⟩.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-124-320.jpg)

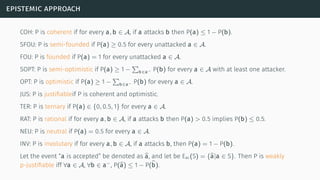

![epistemic approach

[Thi12] [Hun13]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-128-320.jpg)

![epistemic approach

[HT14] [BGV14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-129-320.jpg)

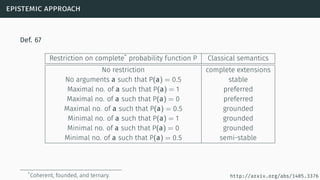

![epistemic approach

An epistemic probability distribution*

for an argumentation framework ∆ = ⟨A, → ⟩ is:

P : A → [0, 1]

Def. 65

For an argumentation framework AF = ⟨A, →⟩ and a probability assignment P, the

epistemic extension is

{a ∈ A | P(a) > 0.5}

*In the tutorial a way to compute it for arguments based on classical deduction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-130-320.jpg)

![structural approach

[Hun14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-133-320.jpg)

![structural approach

P : {∆′

⊑ ∆} → [0, 1]

Subframework Probability

∆1 a ↔ b 0.09

∆2 a 0.81

∆3 b 0.01

∆4 0.09

PGR({a, b}) = = 0.00

PGR({a}) = P(∆2) = 0.81

PGR({b}) = P(∆3) = 0.01

PGR({}) = P(∆1) + P(∆4) = 0.18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-134-320.jpg)

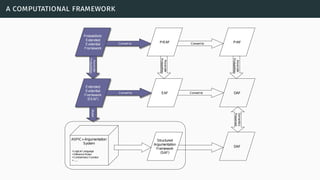

![a computational framework

[Li15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-135-320.jpg)

![[Ton+15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-138-320.jpg)

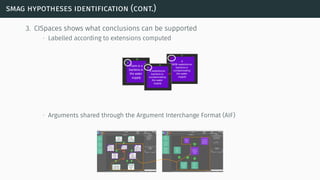

![theories/technologies integrated

∙ Argument representation:

∙ Argument Schemes and Critical questions (domain specific)

∙ „Bipolar-like” graph for user consumption

∙ AIF (extension for provenance)

∙ ASPIC(+)

∙ Arguments based on preferences (partially under development)

∙ Theoretical framework for acceptability status:

∙ AF

∙ PrAF (case study for [Li15])

∙ AFRA for preference handling (under development)

∙ Computational machinery: jArgSemSAT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-159-320.jpg)

![[Cha+15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-161-320.jpg)

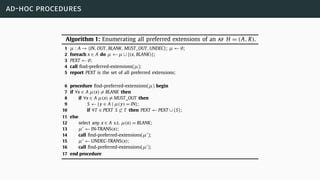

![ad-hoc procedures

ArgTools

[NAD14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-162-320.jpg)

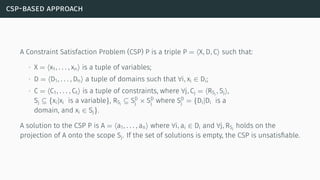

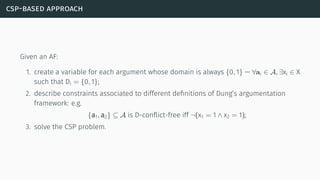

![csp-based approach

ConArg

[BS12]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-164-320.jpg)

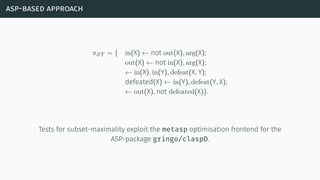

![asp-based approach

ASPARTIX-D / ASPARTIX-V / DIAMOND

[EGW10] [Dvo+11]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-167-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

Cegartix

[Dvo+12]

ArgSemSAT/jArgSemSAT/LabSATSolver

[Cer+14b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-169-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Dvo+12]

∧

a→b

(¬xa ∨ ¬xb)∧

∧

b→c

¬xc ∨

∨

a→b

xa

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-170-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

C1

Lab(a1) = in ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) = out

Lab(a1) = out ⇔ ∃a2 ∈ a−

1 : Lab(a2) = in

Lab(a1) = undec ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) ̸= in ∧ ∃a3 ∈ a−

1 :

Lab(a3) = undec](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-171-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

∧

i∈{1,...,k}

(

(Ii ∨ Oi ∨ Ui) ∧ (¬Ii ∨ ¬Oi)∧(¬Ii ∨ ¬Ui) ∧ (¬Oi ∨ ¬Ui)

)

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−=∅}

(Ii ∧ ¬Oi ∧ ¬Ui) ∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

Ii ∨

∨

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

(¬Oj)

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

∧

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

¬Ii ∨ Oj

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

∧

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

¬Ij ∨ Oi

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

¬Oi ∨

∨

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

Ij

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

∧

{k|ϕ(k)→ϕ(i)}

Ui ∨ ¬Uk ∨

∨

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

Ij

∧

∧

{i|ϕ(i)−̸=∅}

∧

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

(¬Ui ∨ ¬Ij)

∧

¬Ui ∨

∨

{j|ϕ(j)→ϕ(i)}

Uj

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-172-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

Ca

1

Lab(a1) = in ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) = out

Lab(a1) = out ⇔ ∃a2 ∈ a−

1 : Lab(a2) = in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-173-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

Cb

1

Lab(a1) = out ⇔ ∃a2 ∈ a−

1 : Lab(a2) = in

Lab(a1) = undec ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) ̸= in ∧ ∃a3 ∈ a−

1 :

Lab(a3) = undec](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-174-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

Cc

1

Lab(a1) = in ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) = out

Lab(a1) = undec ⇔ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) ̸= in ∧ ∃a3 ∈ a−

1 :

Lab(a3) = undec](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-175-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

C2

Lab(a1) = in ⇒ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) = out

Lab(a1) = out ⇒ ∃a2 ∈ a−

1 : Lab(a2) = in

Lab(a1) = undec ⇒ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) ̸= in ∧ ∃a3 ∈ a−

1 :

Lab(a3) = undec](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-176-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

If a1 is not attacked, Lab(a1) = in

C3

Lab(a1) = in ⇐ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) = out

Lab(a1) = out ⇐ ∃a2 ∈ a−

1 : Lab(a2) = in

Lab(a1) = undec ⇐ ∀a2 ∈ a−

1 Lab(a2) ̸= in ∧ ∃a3 ∈ a−

1 :

Lab(a3) = undec](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-177-320.jpg)

![sat-based approaches

[Cer+14b]

50

60

70

80

90

100

50 100 150 200IPCnormalisedto100

Number of arguments

IPC normalised to 100 with respect to the number of arguments

C1

Ca

1

Cb

1

Cc

1

C2

C3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-178-320.jpg)

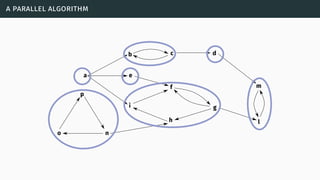

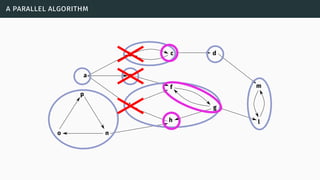

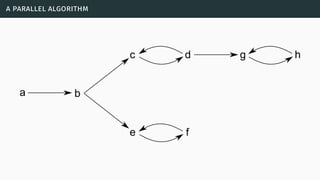

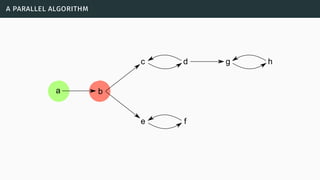

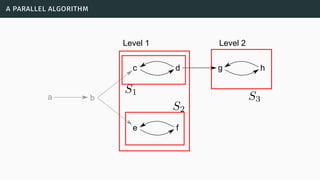

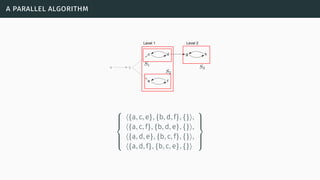

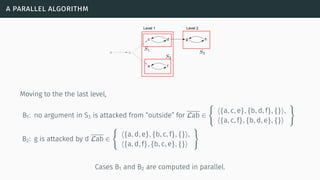

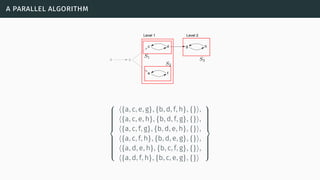

![a parallel algorithm

[BGG05] [Cer+14a] [Cer+15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-183-320.jpg)

![[VCG14] [CGV14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-193-320.jpg)

![belief revision and argumentation

[FKS09] [FGS13]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-203-320.jpg)

![belief revision and argumentation

Potential cross-fertilisation

Argumentation in Belief Revision

∙ Justification-based truth maintenance

system

∙ Assumption-based truth maintenance

system

Some conceptual differences:

in revision, external beliefs are

compared with internal beliefs and,

after a selection process, some

sentences are discarded, other

ones are accepted. [FKS09]

Belief Revision in Argumentation

∙ Changing by adding or deleting an

argument.

∙ Changing by adding or deleting a set of

arguments.

∙ Changing the attack (and/or defeat)

relation among arguments.

∙ Changing the status of beliefs (as

conclusions of arguments).

∙ Changing the type of an argument (from

strict to defeasible, or vice versa).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-204-320.jpg)

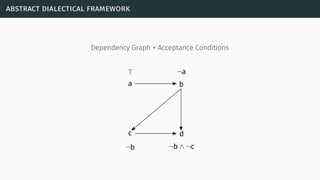

![abstract dialectical framework

[Bre+13]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-205-320.jpg)

![argumentation and social networks

[LM11] [ET13]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-207-320.jpg)

![argumentation and social networks

a:The Wonder-Phone is the

best new generation

phone.

+20 -20

b: No, the Magic-Phone is

the best new generation

phone.

+ 20 - 20

c: here is a [link] to a review

of the Magic-Phone giving

poor scores due to bad

battery performance

+60 -10.

d: author of c is ignorant, since

subsequent reviews noted that

only one of the first editions

had such problems: [links].

+10 -40

e: d is wrong. I found out

c) knows about that but

withheld the information.

Here's a [link] to another

thread proving it!

+40 -10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-208-320.jpg)

![argumentation and social networks

a:The Wonder-Phone is the best

new generation phone.

+20 -20 b: No, the Magic-Phone is the

best new generation phone.

+ 20 - 20

c: here is a [link] to a review

of the Magic-Phone giving

poor scores due to bad

battery performance

+60 -10.

d: author of c is ignorant, since

subsequent reviews noted that

only one of the first editions had

such problems: [links].

+10 -40

e: d is wrong. I found out c)

knows about that but

withheld the information.

Here's a [link] to another

thread proving it!

+40 -10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-209-320.jpg)

![argumentation and social networks

a:The Wonder-Phone is the best

new generation phone.

+20 -20

b: No, the Magic-Phone is the best

new generation phone.

+ 20 - 20

c: here is a [link] to a review of the Magic-

Phone giving poor scores due to bad

battery performance

+60 -10.

d: author of c is ignorant, since subsequent

reviews noted that only one of the first editions

had such problems: [links].

+10 -40

e: d is wrong. I found out c)

knows about that but

withheld the information.

Here's a [link] to another

thread proving it!

+40 -10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-210-320.jpg)

![argument mining

[CV12] [Bud+14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-212-320.jpg)

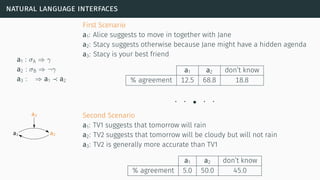

![natural language interfaces

[CTO14] [Cam+14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tutorial-web-150803131119-lva1-app6891/85/Argumentation-in-Artificial-Intelligence-214-320.jpg)