The document presents an empirical evaluation of bridging formal argumentation and natural language interfaces in distributed autonomous systems, emphasizing how reasoning should be presented to enhance human understanding. It details an experiment conducted across four domains with participants assessing the accuracy of arguments based on contradicted claims and preferences, revealing insights into how humans evaluate argument relevance and acceptability. The findings indicate a significant connection between formal argumentation systems and their representation in natural language, highlighting the importance of context and collateral knowledge in human decision-making.

![Post Hoc: Relevance and Agreement

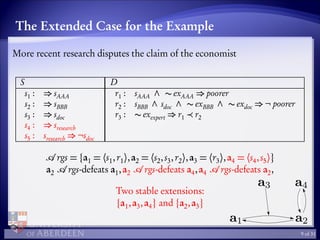

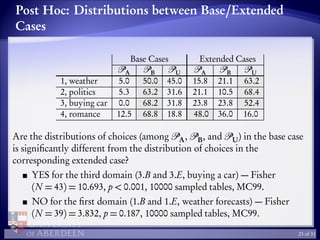

Base cases Extended cases

RB

†

Md∗

B

RE

†

Md∗

E

C.D.‡

Relevance

1, weather 110.38 6.00 82.92 4.00 46.60

2, politics 107.45 6.00 69.45 4.00 47.19

3, buying car 118.05 6.50 67.45 4.00 44.38

4, romance 48.34 2.00 44.40 2.00 46.57

Agreement

1, weather 116.38 6.00 87.18 4.00 46.60

2, politics 103.34 6.00 65.05 4.00 47.19

3, buying car 121.93 6.50 64.33 4.00 44.38

4, romance 44.94 2.00 44.20 2.00 46.57

Statistically significant cases when |Rx − Ry| > C.D.

†

Mean rank as computed with the Kruskal-Wallis test

‡

Critical Difference, as computed in [Siegel and Castellan Jr., 1988] cited

by [Field, 2009] with α = 0.05.

25 of 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/argument-experiment-140922134847-phpapp02/85/Formal-Arguments-Preferences-and-Natural-Language-Interfaces-to-Humans-an-Empirical-Evaluation-25-320.jpg)

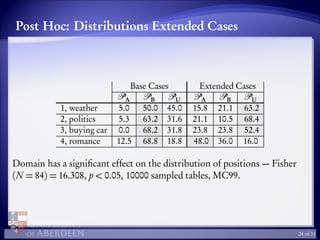

![Post Hoc: Relevance and Agreement

Scenario 3.B Scenario 4.B

R3.B

†

Md∗

3.B

R4.B

†

Md∗

4.B

C.D.‡

Relevance 118.05 6.50 48.34 2.00 47.79

Agreement 121.93 6.50 44.94 2.00 47.79

Statistically significant cases when |Rx − Ry| > C.D.

†

Mean rank as computed with the Kruskal-Wallis test

‡

Critical Difference, as computed in [Siegel and Castellan Jr., 1988] cited

by [Field, 2009] with α = 0.05.

26 of 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/argument-experiment-140922134847-phpapp02/85/Formal-Arguments-Preferences-and-Natural-Language-Interfaces-to-Humans-an-Empirical-Evaluation-26-320.jpg)

![References I

[Field, 2009] Field, A. (2009).

Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (Introducing Statistical Methods series).

SAGE Publications Ltd.

[Siegel and Castellan Jr., 1988] Siegel, S. and Castellan Jr., N. J. (1988).

Nonparametric Statistics for The Behavioral Sciences.

McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

31 of 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/argument-experiment-140922134847-phpapp02/85/Formal-Arguments-Preferences-and-Natural-Language-Interfaces-to-Humans-an-Empirical-Evaluation-31-320.jpg)