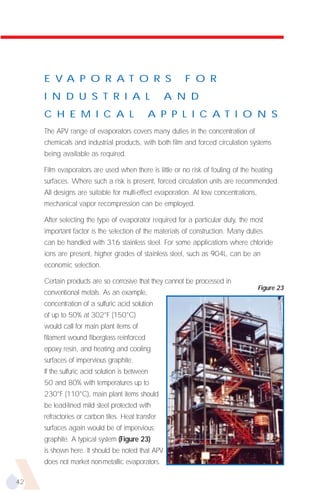

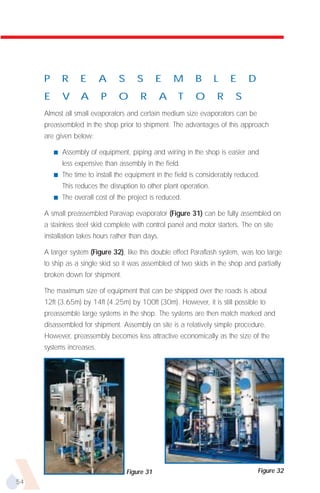

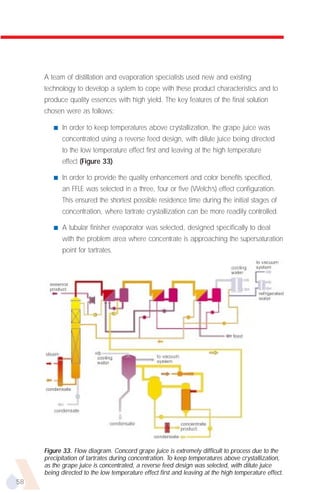

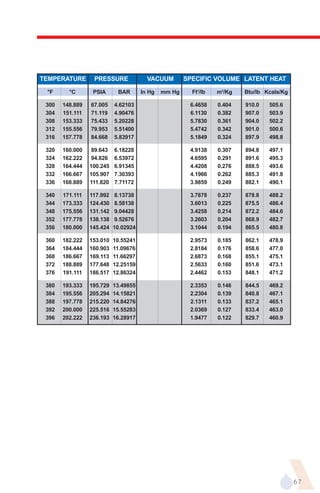

The document provides an overview of evaporator types and design considerations. It discusses several types of evaporators including batch pans, natural circulation tubular evaporators, rising film tubular evaporators, falling film tubular evaporators, rising/falling film tubular evaporators, forced circulation evaporators, wiped film evaporators, and plate evaporators. It focuses on describing the operation and applications of plate evaporators, specifically rising/falling film plate evaporators.

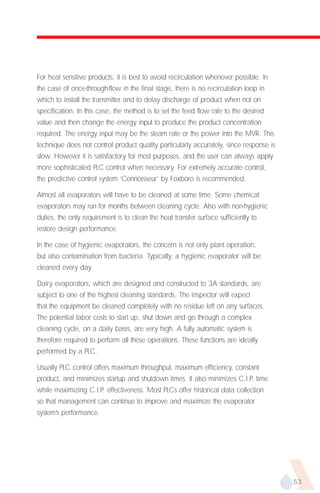

![ESTIMATING RESIDENCE TIME

It is difficult to estimate the residence time in film evaporators, especially rising film

units. Correlations, however, are available to estimate the volume of the channel

occupied by liquid. Formula (1) is recommended for vacuum systems.

For falling film evaporators, the film thickness without vapor shearing can be

calculated by Formula (2).

Since the film is thin, this can be converted to liquid volume fraction in a tubular

evaporator by Formula (3).

For a falling film plate evaporator, Formula (4) is used. As liquid travels down the plate

and evaporation starts, vapors will accelerate the liquid. To account for this action, the

rising film correlation is used when the film thickness falls below that of a falling film

evaporator. In practice, the film thickness may be less than estimated by either method

because gravity and vapor momentum will act on the fluid at the same time.

Once the volume fraction is known, the liquid residence time is calculated by

formula (5). In order to account for changing liquid and vapor rates, the volume

fraction is calculated at several intervals along the channel length. Evaporation is

assumed to be constant along with channel length except for flash due to high

feed temperature.

SYMBOLS FORMULAS

A cross sectional area 1

d tube diameter (1) RL = 1 –

( ) ( 2ρρ )

.5

1+ 1–y V

g gravitational constant y L

L tube length

m film thickness

3Γµ

[ ]

1

RL liquid volume fraction /3

(2) m=

g ρL ( ρL – ρv )

qL liquid rate

t time

Γ liquid wetting rate

ρL liquid density 4m

ρV vapor density

(3) RL =

d

µ liquid viscosity

y local weight fraction of vapor 2m

(4) RL =

References Z

a) HTRI report, BT-2, pg. 7 (May

1978) RL AL

(5) t=

qL

b) Perry's Chemical Engineer's

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apvevaporatorhandbook-100803121603-phpapp02/85/Apv-Evaporator-Handbook-30-320.jpg)