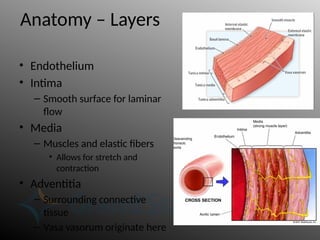

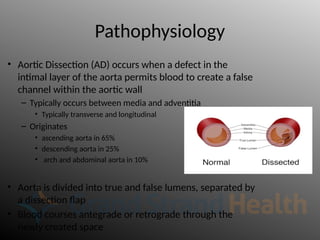

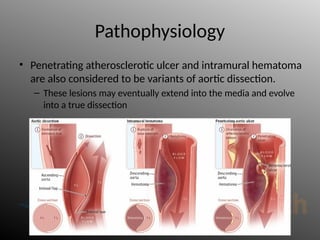

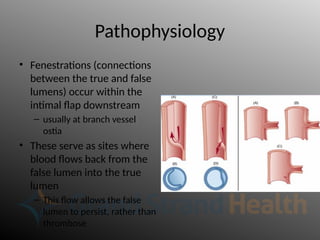

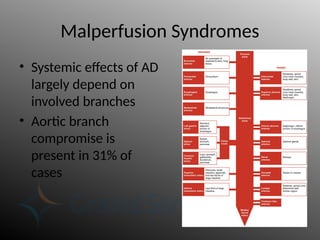

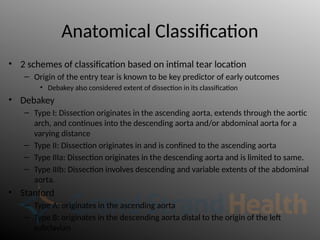

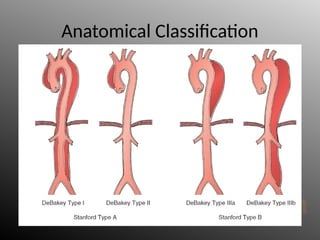

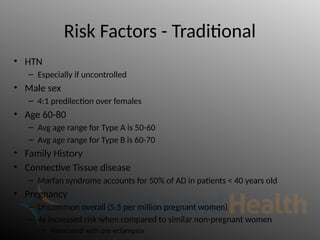

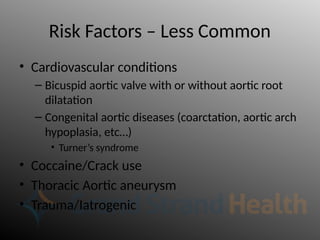

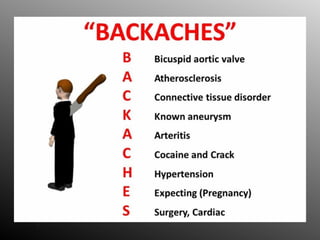

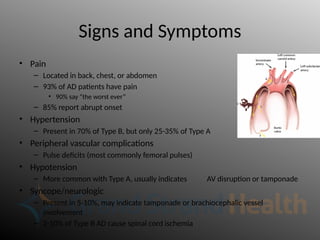

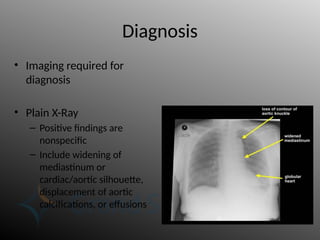

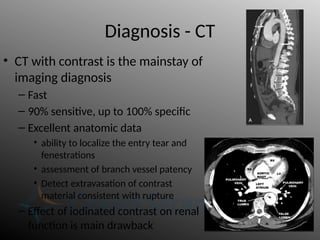

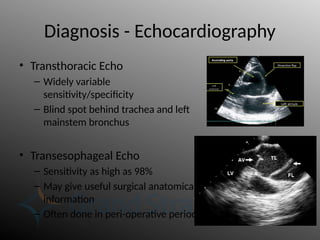

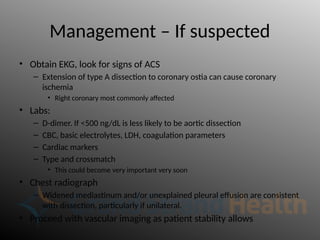

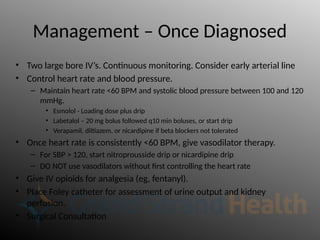

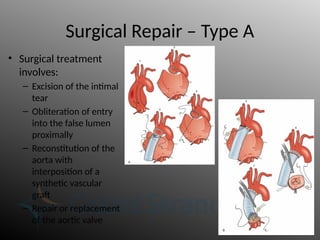

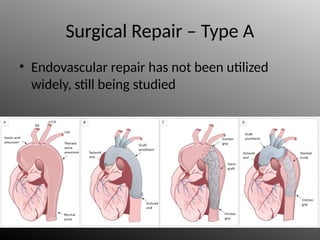

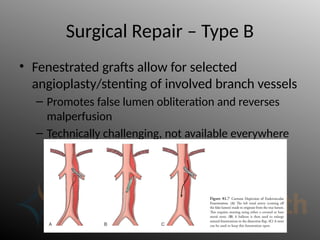

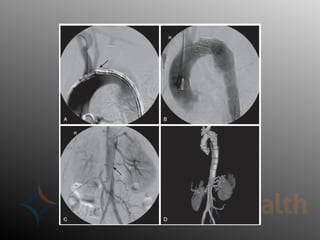

Aortic dissection is a severe condition affecting the aorta, with high mortality if untreated, and is classified based on the location of the tear. Diagnosis relies on imaging techniques, primarily CT with contrast, and management may require surgical intervention for type A dissections or medical management for type B cases. Key risk factors include hypertension, male sex, and connective tissue diseases, while symptoms often include severe chest or back pain and hypertension.