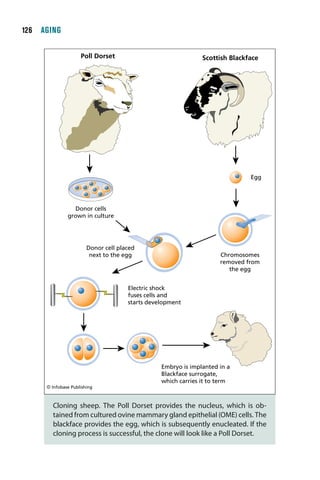

This document provides an introduction to the revised edition of the book "Aging" by Joseph Panno. It discusses how aging is a universal phenomenon among complex multicellular organisms but not simpler life forms. While research has generated many theories on aging, practical therapies to reverse aging have been limited. The revised edition expands on topics like longevity genes, cloning, stem cells, and genetic manipulation, which may help develop effective rejuvenation therapies to slow the aging process.