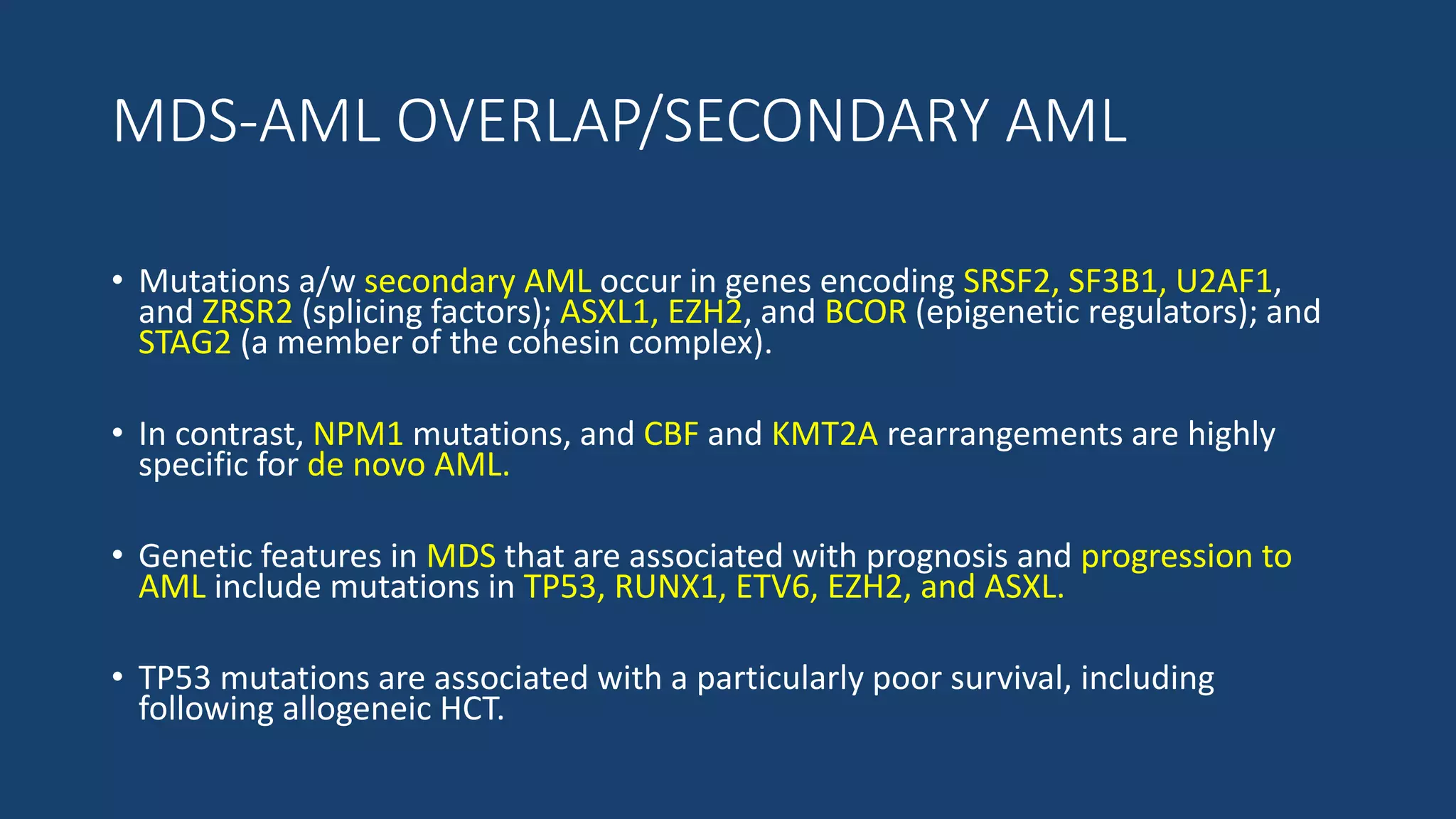

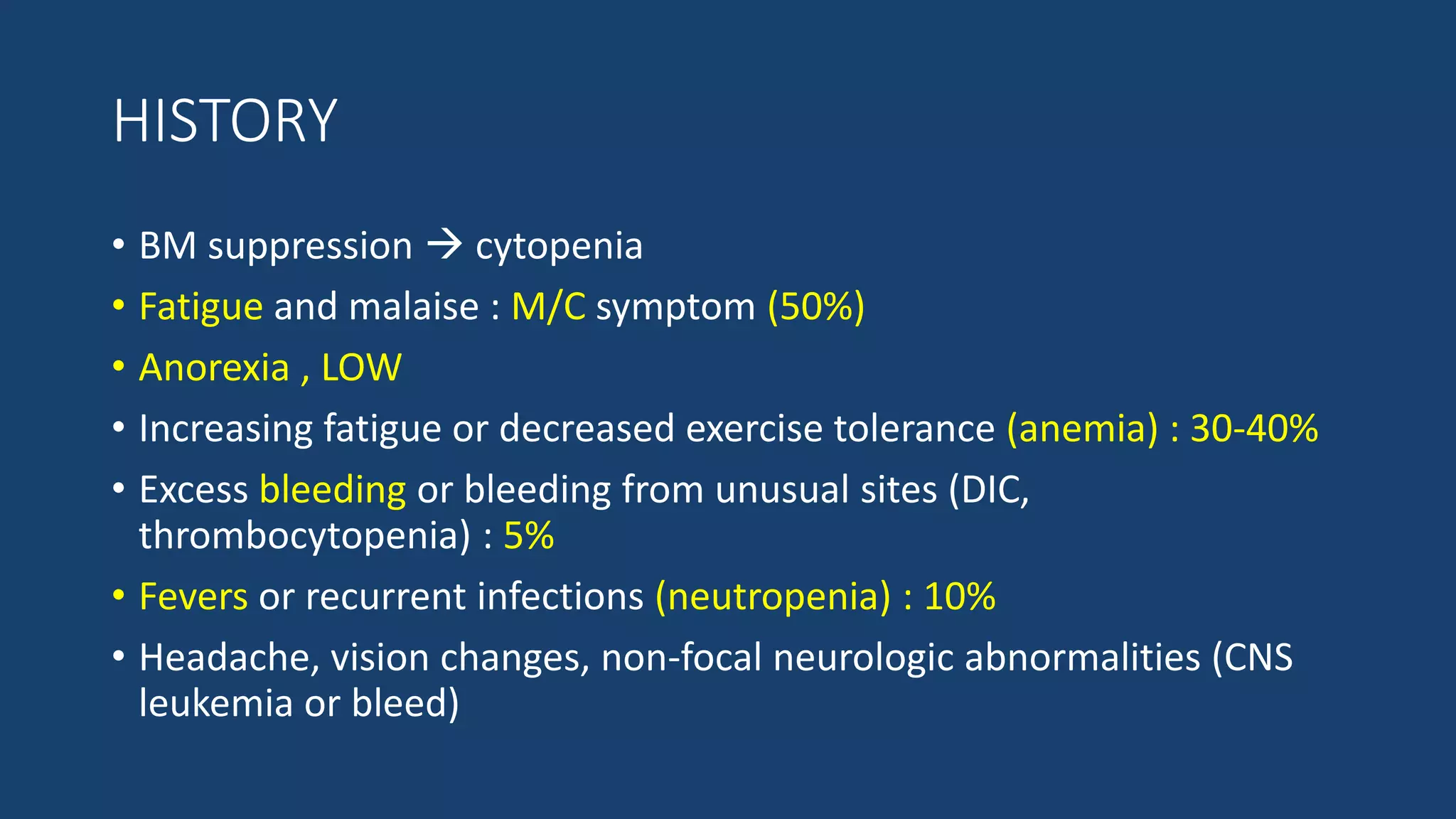

This document provides an overview of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). It discusses the historical background, classification, clinical features, risk stratification, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment regimens for AML. Key points include that AML is characterized by infiltration of blood and bone marrow by proliferative myeloid cells, the WHO classification system is based on clinical features, morphology, cytogenetics and molecular abnormalities, risk is stratified by cytogenetics and molecular markers, and treatment involves supportive care, induction chemotherapy, and consideration of novel targeted therapies or stem cell transplant depending on risk factors.

![• Gum hypertrophy (leukemic infiltration, most common in monocytic

leukemia)

• Skin infiltration or nodules (leukemia infiltration, most common in

monocytic leukemia)

• Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly

• Back pain, lower extremity weakness [spinal granulocytic sarcoma,

most likely in t(8;21) patients]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acutemyeloidleukemia-190101161606/75/Acute-myeloid-leukemia-27-2048.jpg)