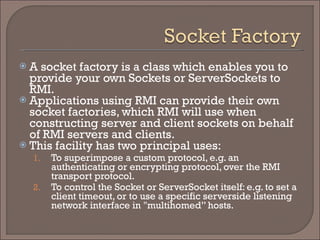

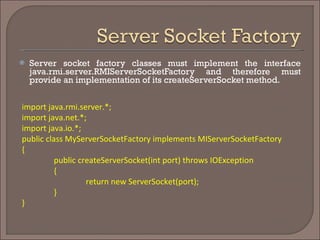

Lazy activation in RMI allows remote objects to begin execution only when they are first accessed, rather than all being activated upfront. A faulting remote reference contains both an activation ID and a potential live reference. When a method is first invoked, if the live reference is null, the activation ID is used to look up and activate the object. The activated object's live reference is then returned and used for subsequent invocations. Socket factories in RMI allow customizing how server and client sockets are created, such as for authentication or controlling which network interface is bound.