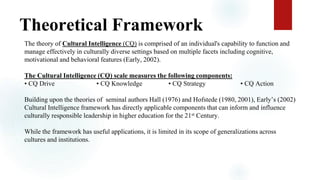

This document discusses the need for cultural competence among administrative leaders in higher education, particularly as institutions begin internationalization efforts. It explores leaders' perceptions of cultural intelligence, which is crucial for fostering an inclusive environment and enhancing global engagement. The study aims to bridge existing research gaps by providing insights that will inform professional development policies for higher education leaders.