This document provides a summary of a book titled "A Practical Guide for Translators". The book is intended to provide practical advice for those entering the translation profession or looking to improve their skills. It covers topics such as how to become a translator, running a translation business, tools and software, quality control, and professional organizations. The fourth edition has been updated to reflect changes in the industry, including a greater focus on the business aspects of translation and working as a freelancer. The author draws on their experience working as a staff translator, freelancer, and running a translation company.

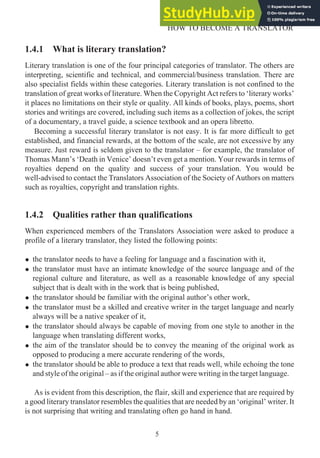

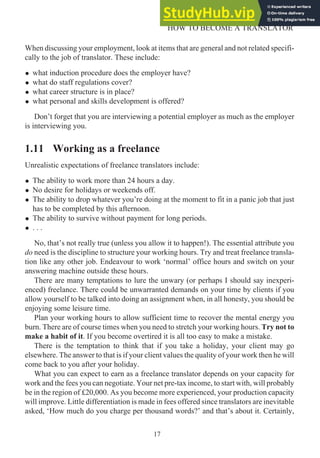

![dents earned less than GBP 15,000 a year. The survey also states ‘The average hourly

rate of GBP 24.61 for translation companies is less than that of most skilled tradesmen

while a significant number of respondents charge the same rates as secretarial services’.

What you need to consider is whether or not you think the fees you can charge are

reasonable recompense for the years of study and the debts you have incurred. You have

several choices:

1. Consider some other profession

2. Accept the relatively low fees that are on offer

3. Negotiate more acceptable fees that are appropriate to your education, qualifica-

tions and experience.

Not until translators decline to accept work that pays low rates will there be any change.

Some while back a translation company recently sent the following email to its freelances.

45

RUNNING A TRANSLATION BUSINESS

Dear Translator,

I am writing from XXXXX (also known as YYYYY Ltd) and as you know, you are registered on our

database as a freelance translator.

XXXXX, one of Europe’s largest Language Management companies, has been chosen by over half of the

FTSE 100 for translations between 115 languages. This is due to exceptional responsiveness and

quality. We continue to grow our business and secure major new contracts with some of the largest

companies in the world.

However, the market for translation is tightening and we are experiencing real pressure on our prices,

experiencing reductions in the region of 15%. Customers are negotiating very hard before placing work

with us and we believe this situation is not just for XXXXX but is industry-wide. In order to ensure our

continued competitiveness we are expecting you to reduce your prices also.

We hold our translators in the highest regard and recognise their immense contribution to the success of

XXXXX . We would like to carry on the good working relationship already existing between XXXXX and its

suppliers. We will only be able to do so if our suppliers (this means you) accept to reduce their rates.

As from ZZZZ 1st 2002, with immediate effect, we expect our translation suppliers to reduce their rates

significantly. As you know XXXXX is regarded as highly professional and pay their suppliers on time. I

hope that you will continue to be part of XXXXX and I look forward to our future relationship.

Thanking you for you [sic] interest in XXXXX .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apracticalguidefortranslators-230806182710-66e63475/85/A-Practical-Guide-For-Translators-60-320.jpg)

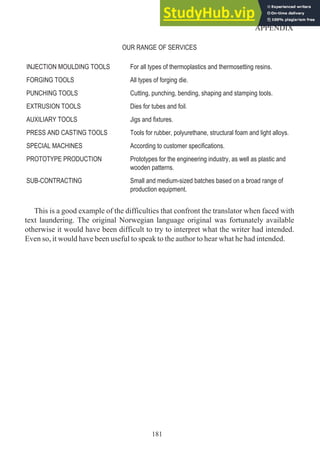

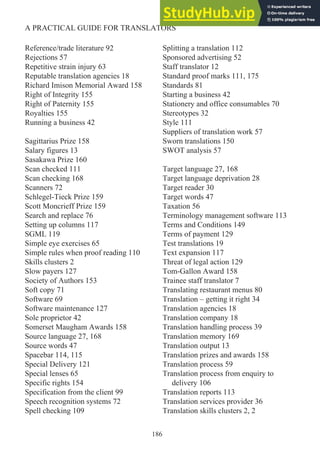

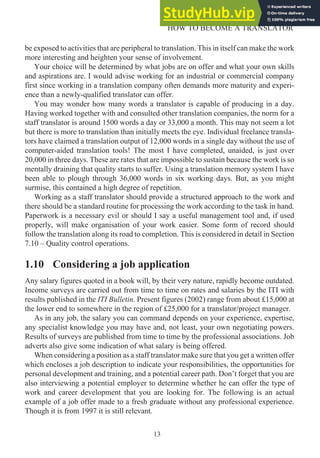

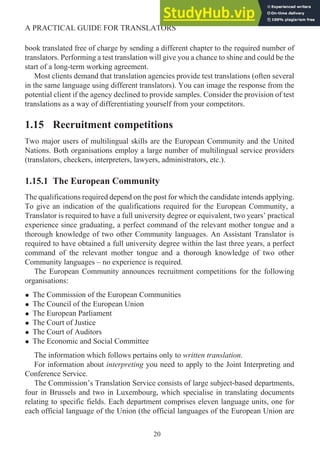

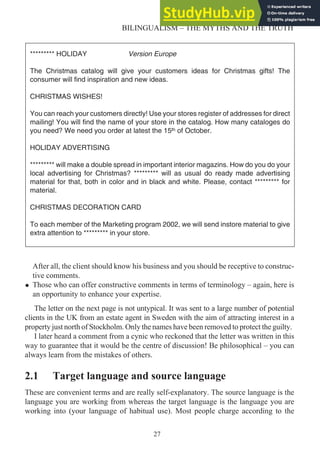

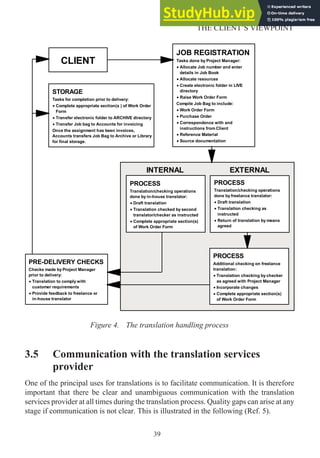

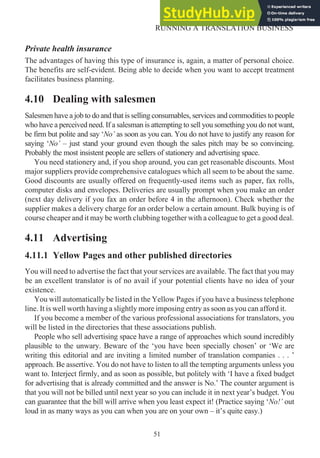

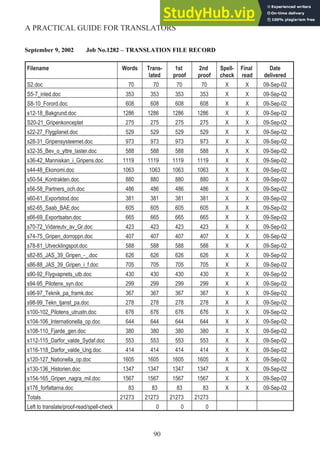

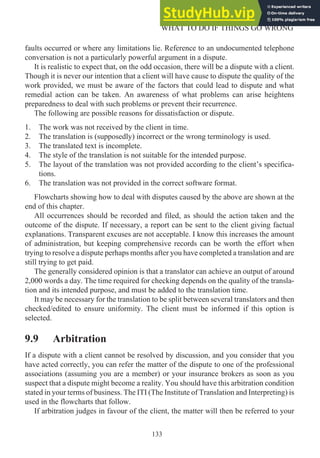

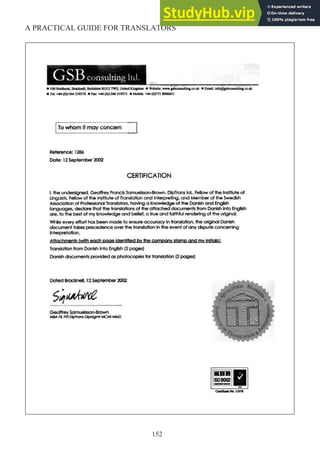

![[Fontsize+2]

[BoldItalics][centre]The

Constitution of the[hardReturn]

United States of America

[fontNormal][fontsize2]

PREAMBLE[leftjustify][all caps] We

the people [notall caps] of the

United States, in order to form a

more perfect[italics] Union,

[fontNormal] establish justice,

insure domestic tranquility,

provide for the common defense,

promote the general welfare, and

secure the blessings of liberty to

ourselves and our posterity, do

ordain and establish this

Constitution for the United States

of America.

The Constitution of the

United States of America

PREAMBLE

WE THE PEOPLE of the United States,

in order to form a more perfect Union,

establish justice, insure domestic

tranquility, provide for the common

defense, promote the general welfare,

and secure the blessings of liberty to

ourselves and our posterity, do ordain

and establish this Constitution for the

United States of America.

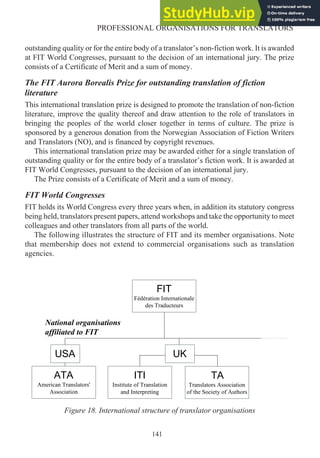

Figure 17. Example of SGML mark-up

8.8 Getting the translation to the client

There are several ways of getting work to your client depending on urgency. Before you

agree to send any work to a client by a method that incurs additional costs, make sure you

agree with the client who should pay. If the urgency is demanded by the client then the

client should pay. The options available are: post, fax, electronic mail and couriers. You

can of course deliver the translation yourself but this is seldom practical and your time is

too valuable to act as an unpaid courier.

Most of the options considered in the first edition of this book have now been super-

seded by the use of electronic mail but are still worth mentioning since original documents

such as certified translations and original will need to be sent by post or courier.

Postal service

For the most part, the Post Office provides an acceptable service with a large

percentage of first class deliveries reaching their destination the next day. There are

120

A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR TRANSLATORS

The Constitution of the United States of America PREAMBLE We the people

of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish

justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense,

promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to

ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution

for the United States of America.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apracticalguidefortranslators-230806182710-66e63475/85/A-Practical-Guide-For-Translators-135-320.jpg)

![When a translation is sworn before a solicitor, the solicitor does not verify the quality

of the translation but merely satisfies himself as to the translator’s identity. Certification

does, however, lend weight to a translation. If, for example, a document is wilfully

mistranslated or carelessly translated, the translator could be held charged with contempt

of court, perjury or negligence.

Acceptability of ITI certification by the authorities

The legal advice taken by the ITI is that ‘a certificate is acceptable if it is accepted’ and

that we as suitably qualified translators should certify translations and wait to see

whether such a certificate is challenged and, if so, by whom. The ITI’s advisors feel that

such a challenge is unlikely or, that by the time a challenge does arise, a firm precedent

will have been set. To my knowledge, only one challenge has been made against ITI

certification since the scheme has been in operation.

When users of translations insist on a higher grade of certification, they should be

reminded of the existence of notarisation and referred to notaries (and where practicable

to firms whose members are ITI members). Comprehensive details are given in guide-

lines issued by the ITI.

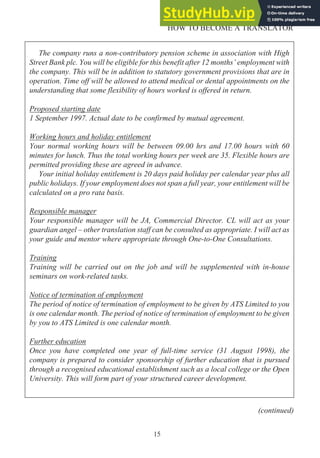

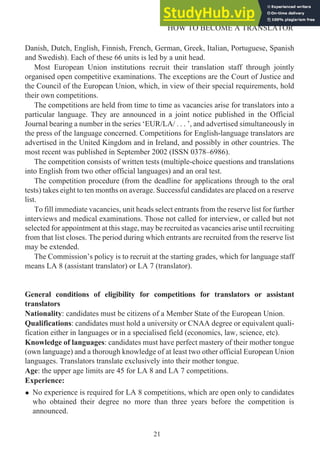

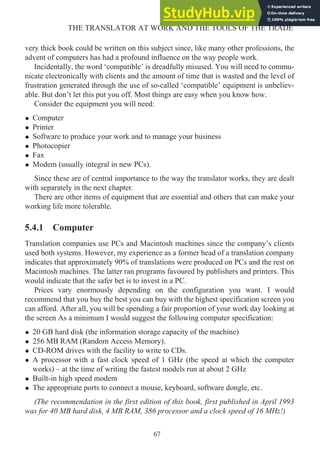

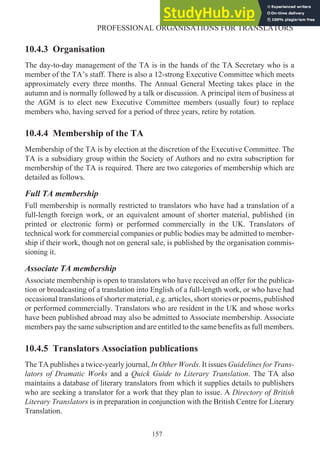

Example certification

A scanned example of certification is given on the next page.

The wording of the certification should be as follows:

I, the undersigned, [Name], Fellow/Member of the Institute of Translation and Inter-

preting, [other qualifications] declare that the translation of the attached document(s)

[identifying particulars] is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, a true and faithful

rendering of the original [language], done to the best of my ability as a professional

translator [and verified by (name and ITI membership qualification)]

[Signature]

Attachments:

A1. Document (brief identification)

A2. Translation of A1

B1. Document (brief identification)

B2. Translation of B1

. . . etc.

151

PROFESSIONAL ORGANISATIONS FOR TRANSLATORS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apracticalguidefortranslators-230806182710-66e63475/85/A-Practical-Guide-For-Translators-166-320.jpg)

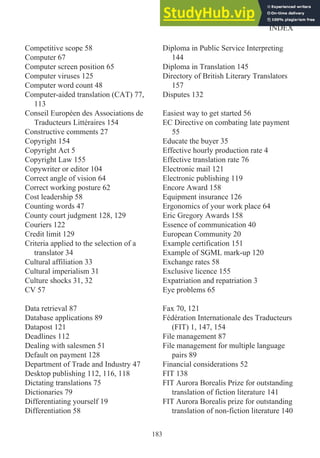

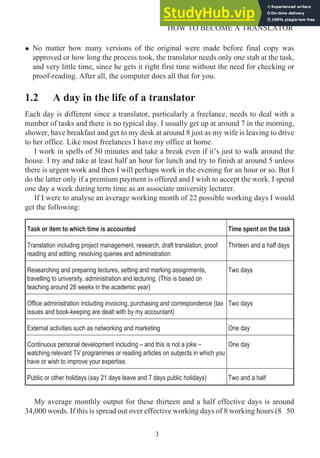

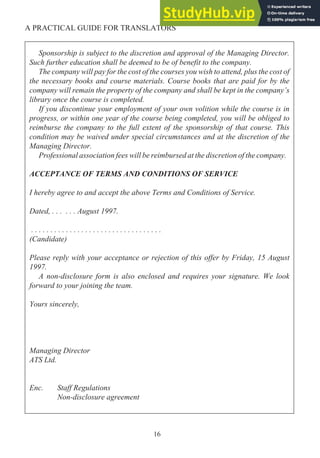

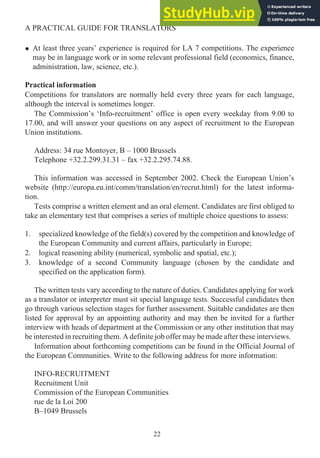

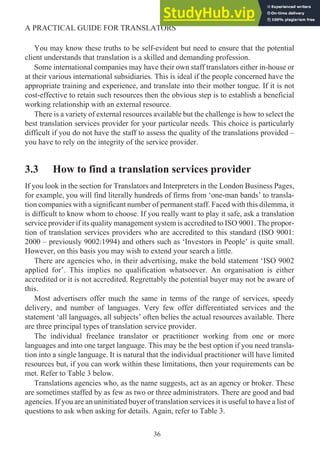

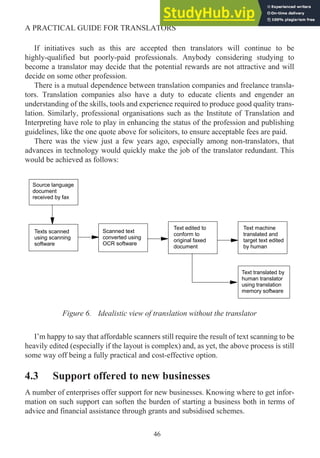

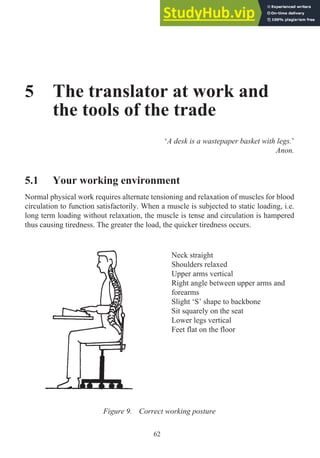

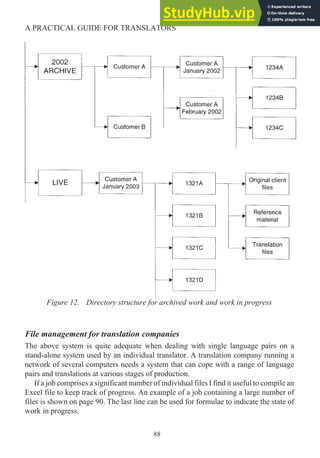

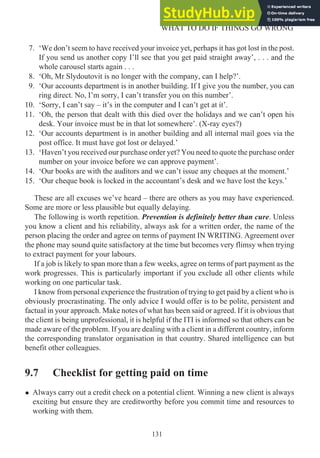

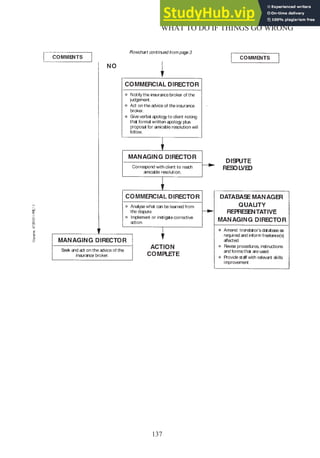

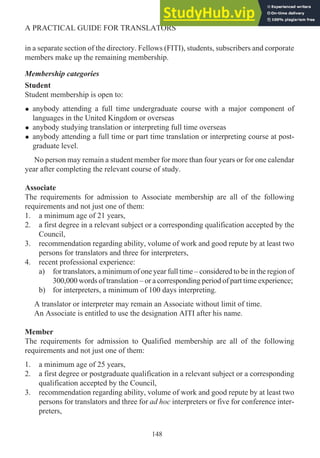

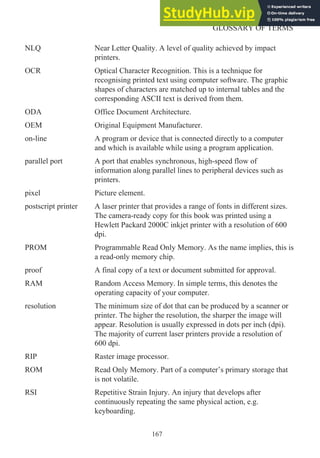

![12.4.1 ASCII Standard Character Set

The appropriate characters can be obtained by pressing the Alt key and the relevant code

numbers (on the numeric keypad) at the same time.

ASCII number Character ASCII number Character ASCII number Character

033

034

035

036

037

038

039

040

041

042

043

044

045

046

047

048

049

050

051

052

053

054

055

056

057

058

059

060

061

062

063

064

!

"

#

$

%

&

'

(

)

*

+

,

-

.

/

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

:

;

<

=

>

?

@

065

066

067

068

069

070

071

072

073

074

075

076

077

078

079

080

081

082

083

084

085

086

087

088

089

090

091

092

093

094

095

096

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

[

]

^

_

`

097

098

099

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

t

u

v

w

x

y

z

{

|

}

~

173

APPENDIX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apracticalguidefortranslators-230806182710-66e63475/85/A-Practical-Guide-For-Translators-188-320.jpg)