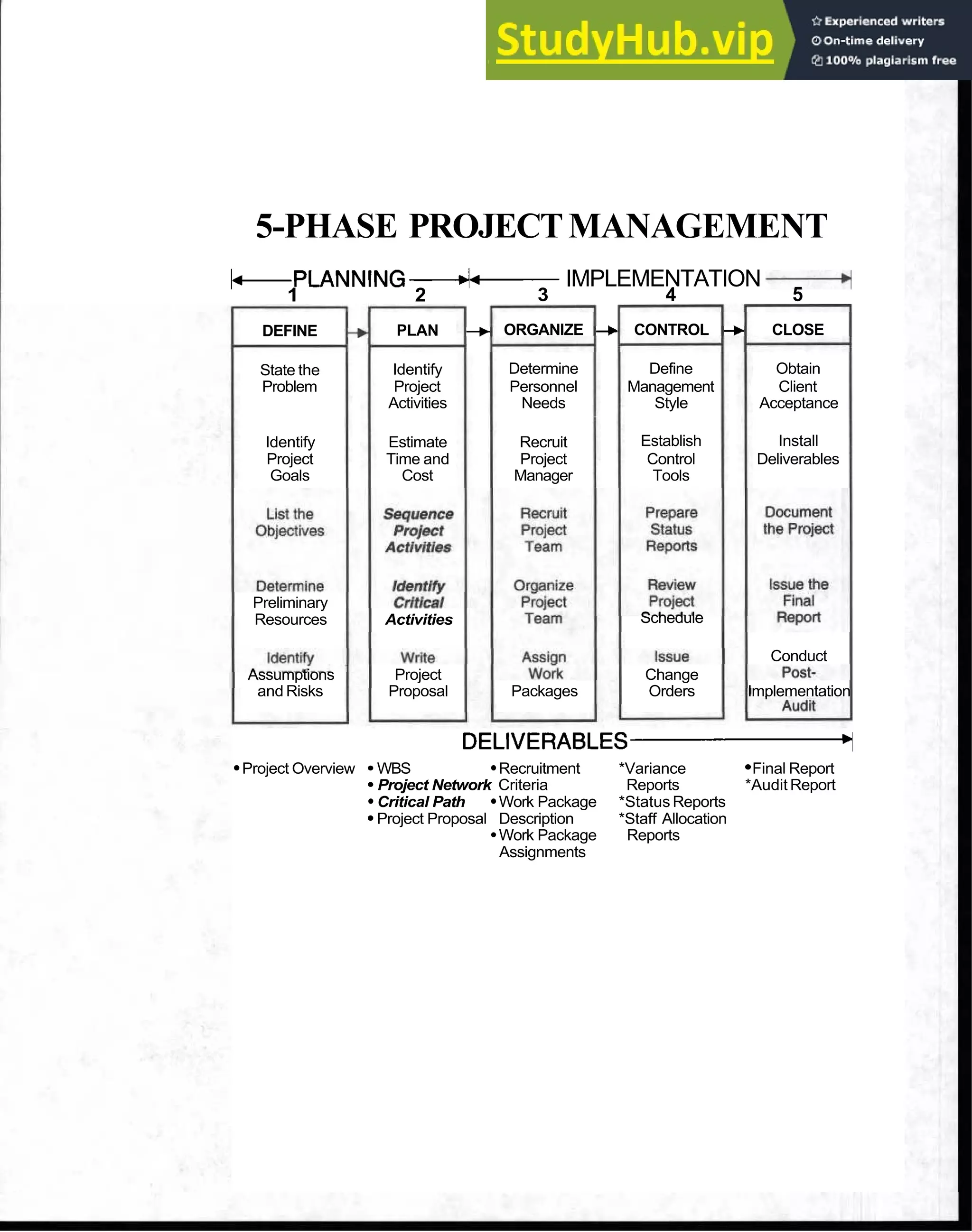

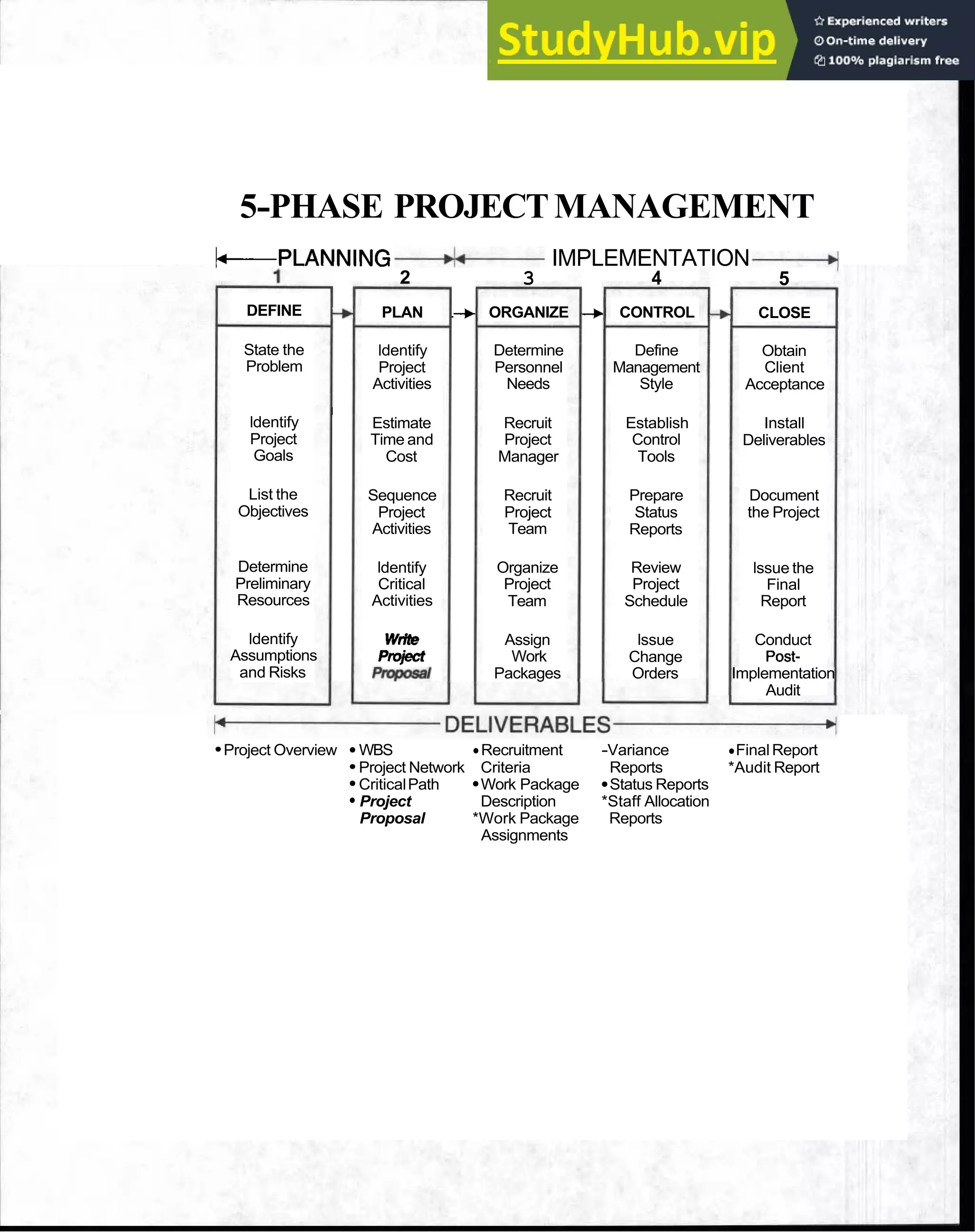

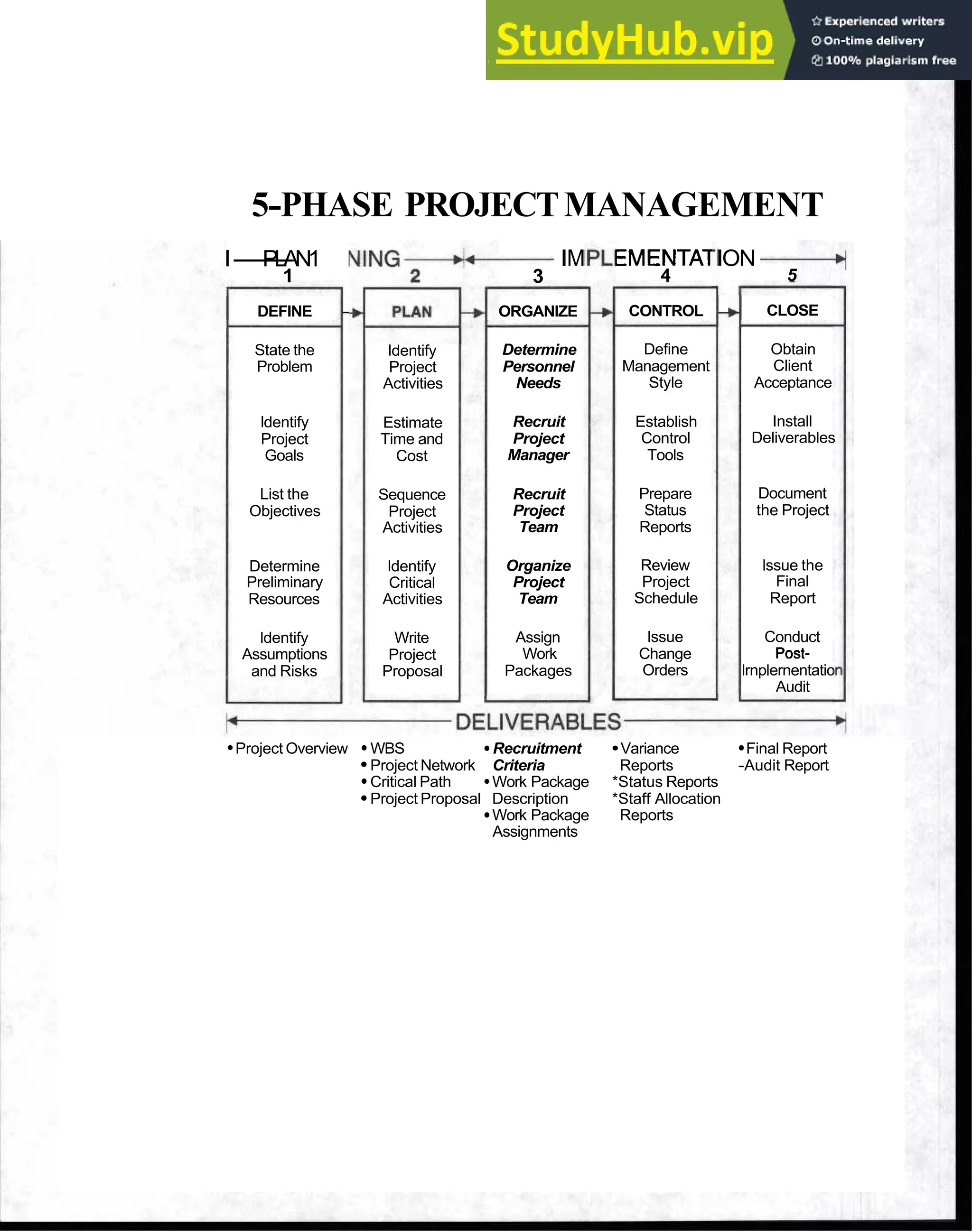

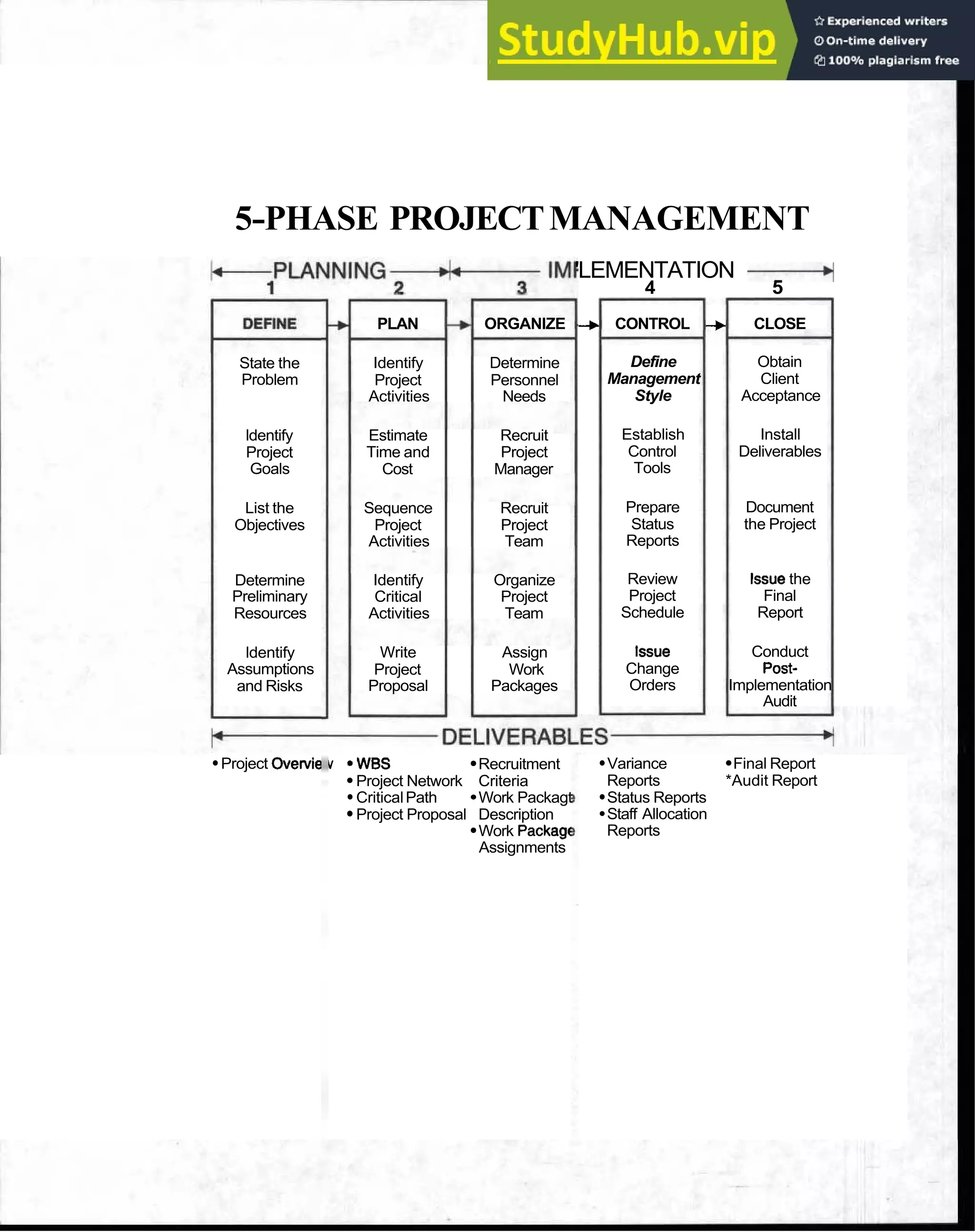

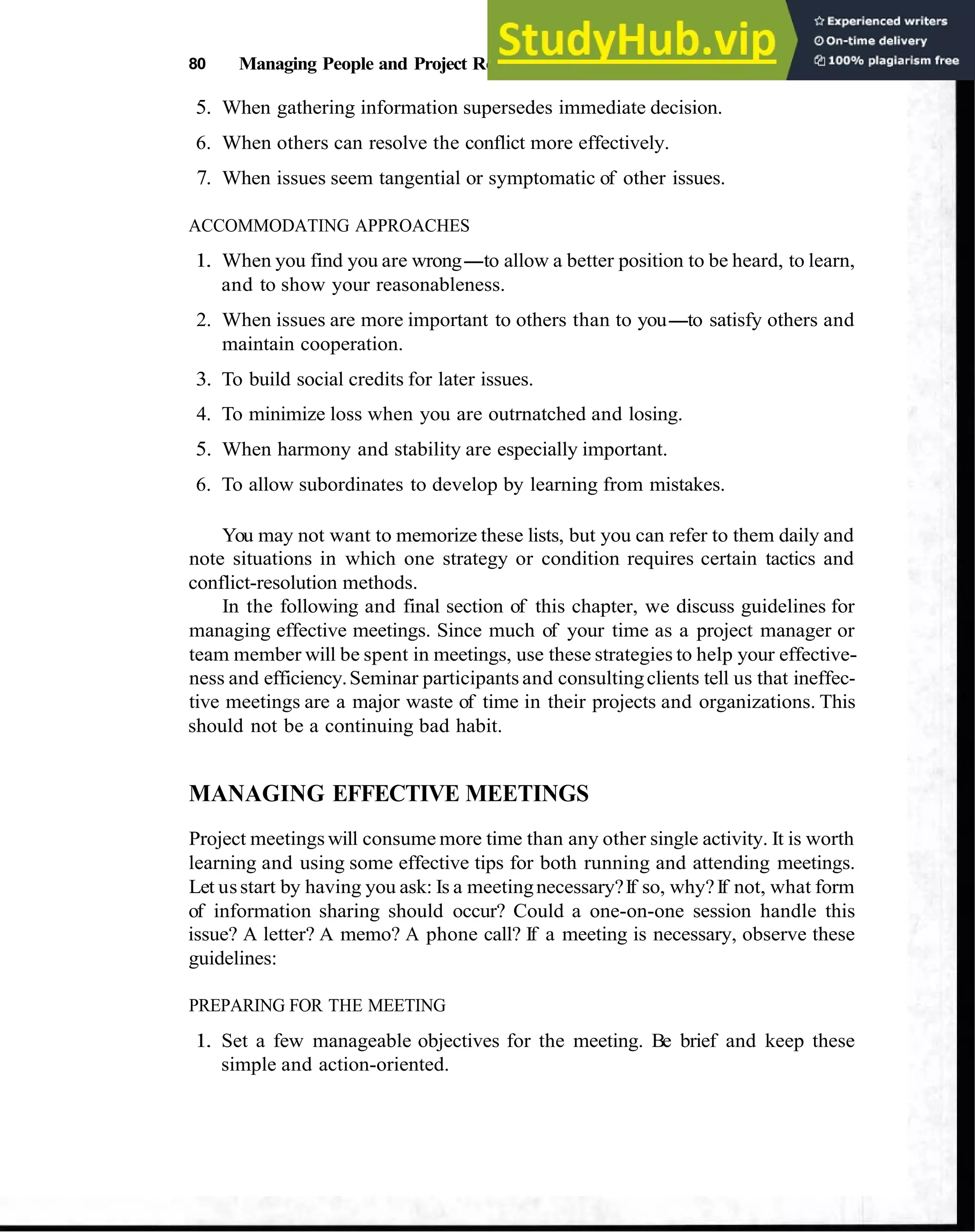

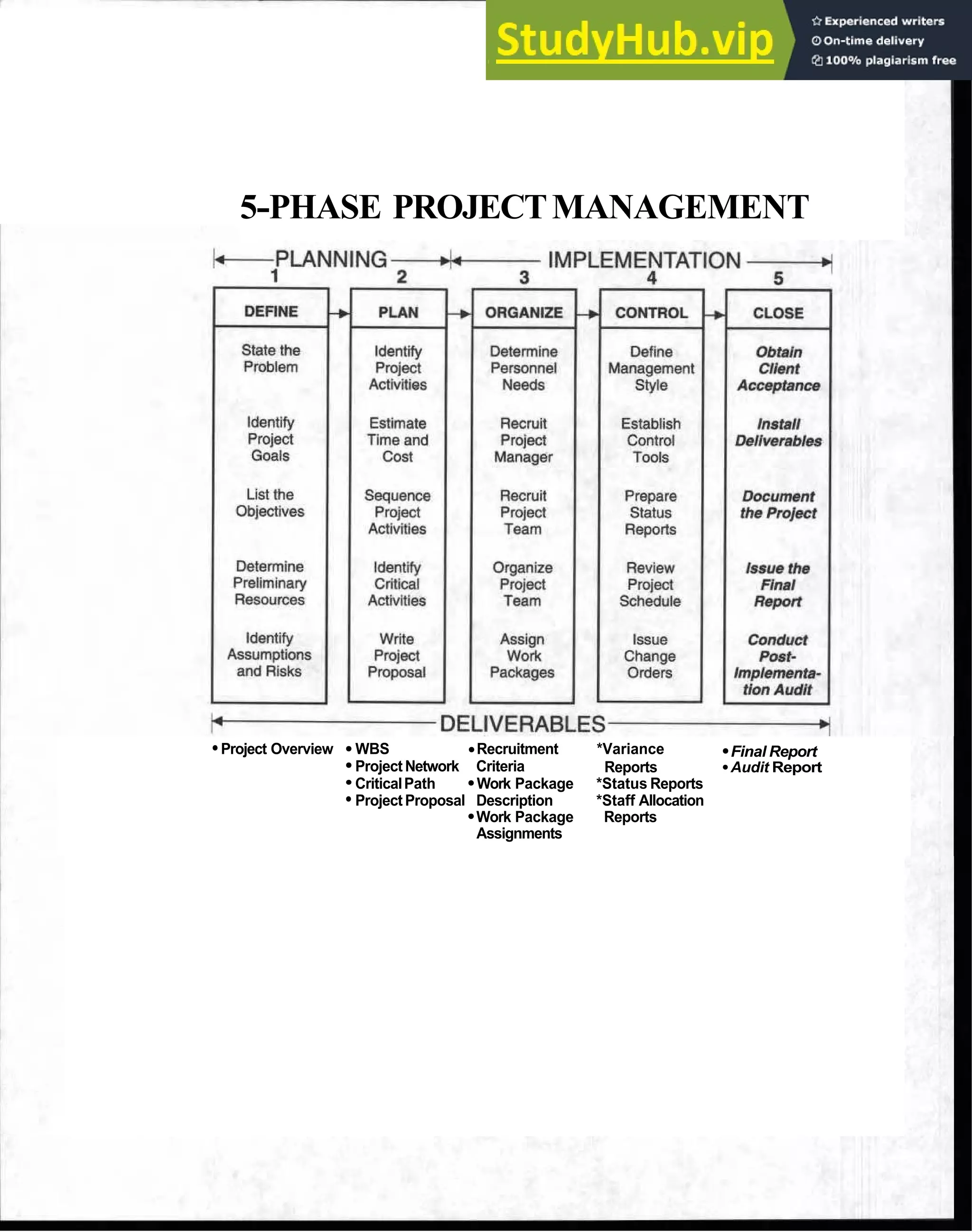

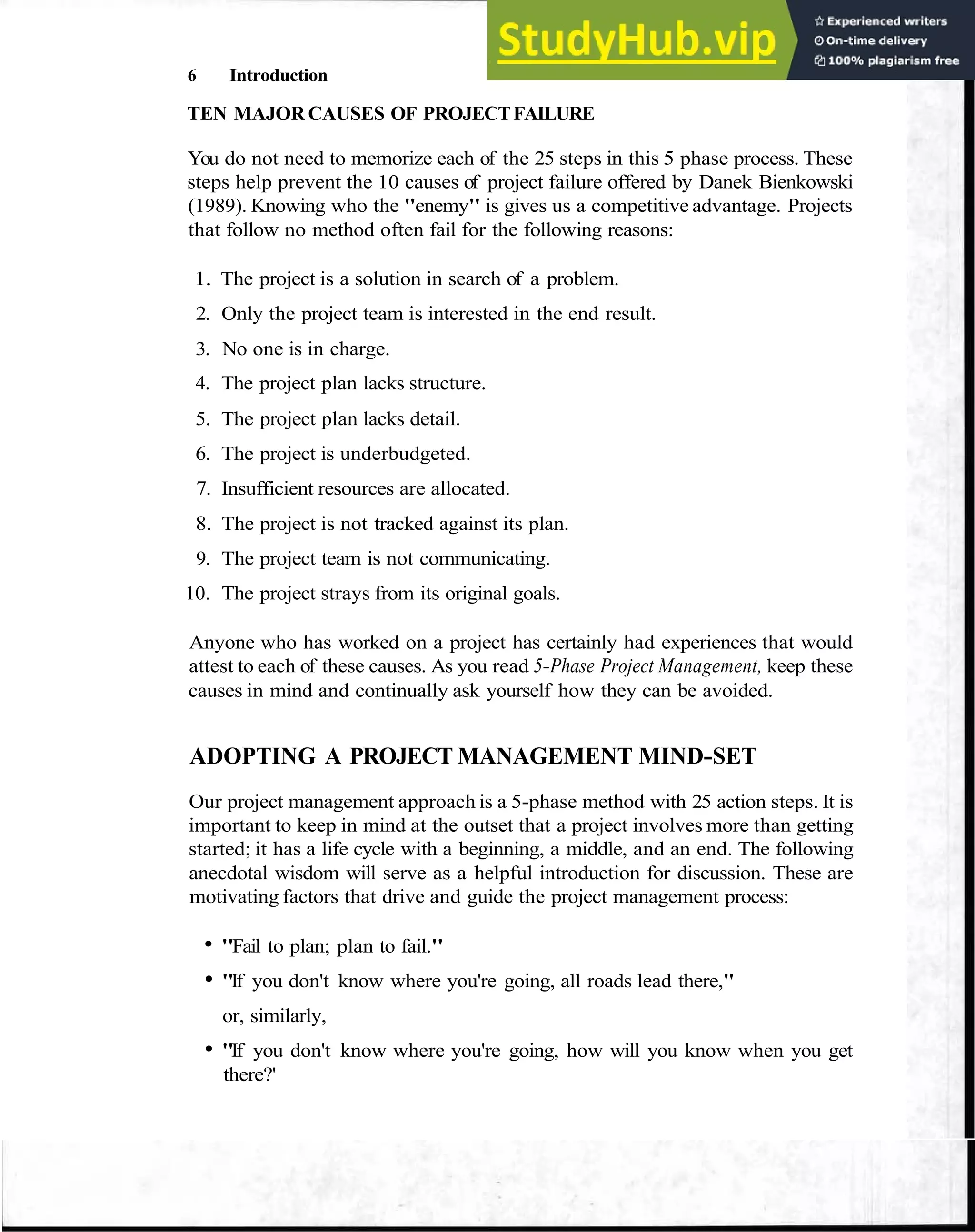

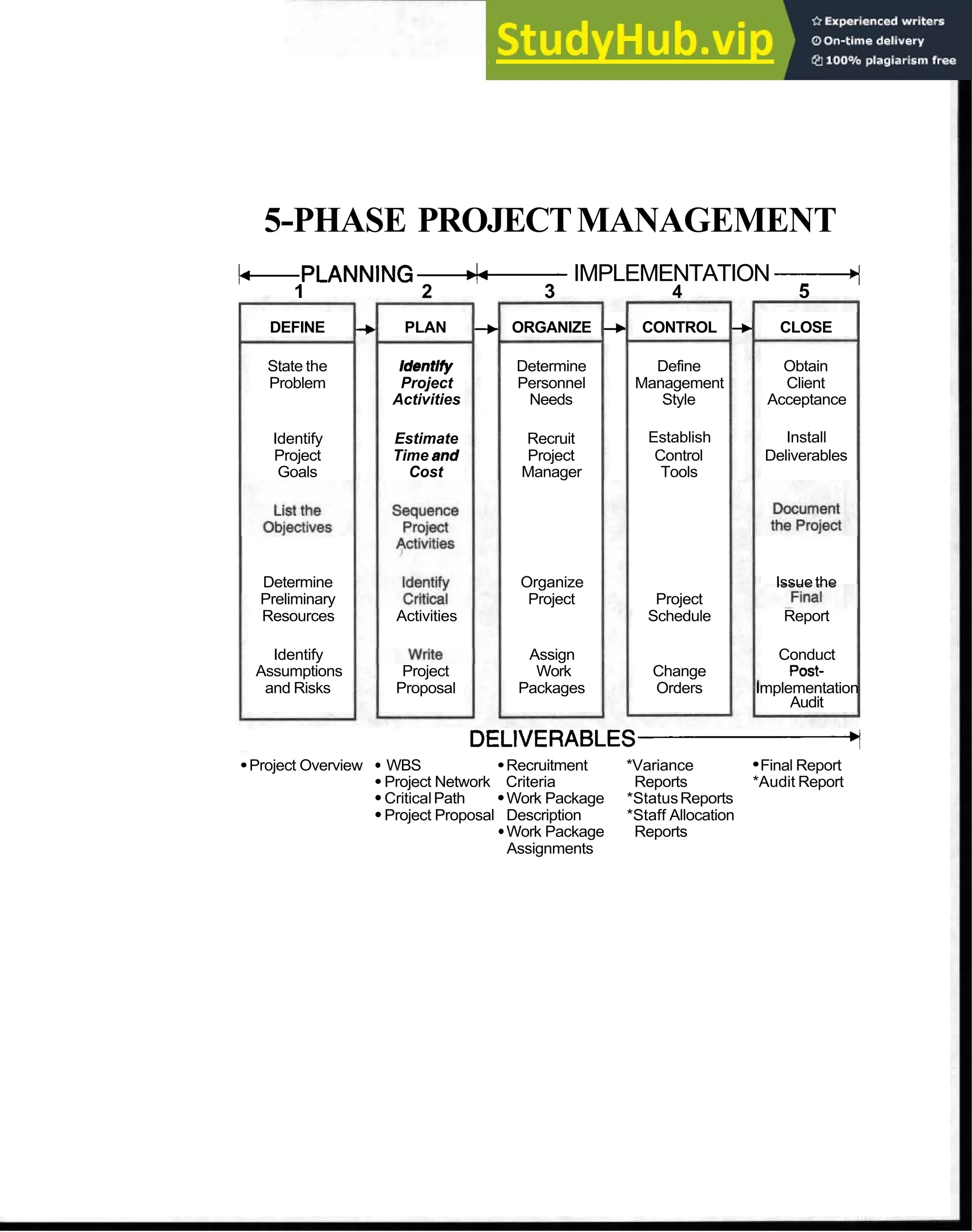

This document provides an overview of a book titled "5-Phase Project Management" which outlines a practical approach to project planning and implementation using a 5-phase process. The phases include defining the project, specifying the project activities and tasks, sequencing the activities, writing a project proposal, and implementing and closing out the project. The book is intended to help readers from any industry or profession effectively plan and manage projects with limited resources and tight deadlines.

![Work Breakdown Structures (WBS) 27

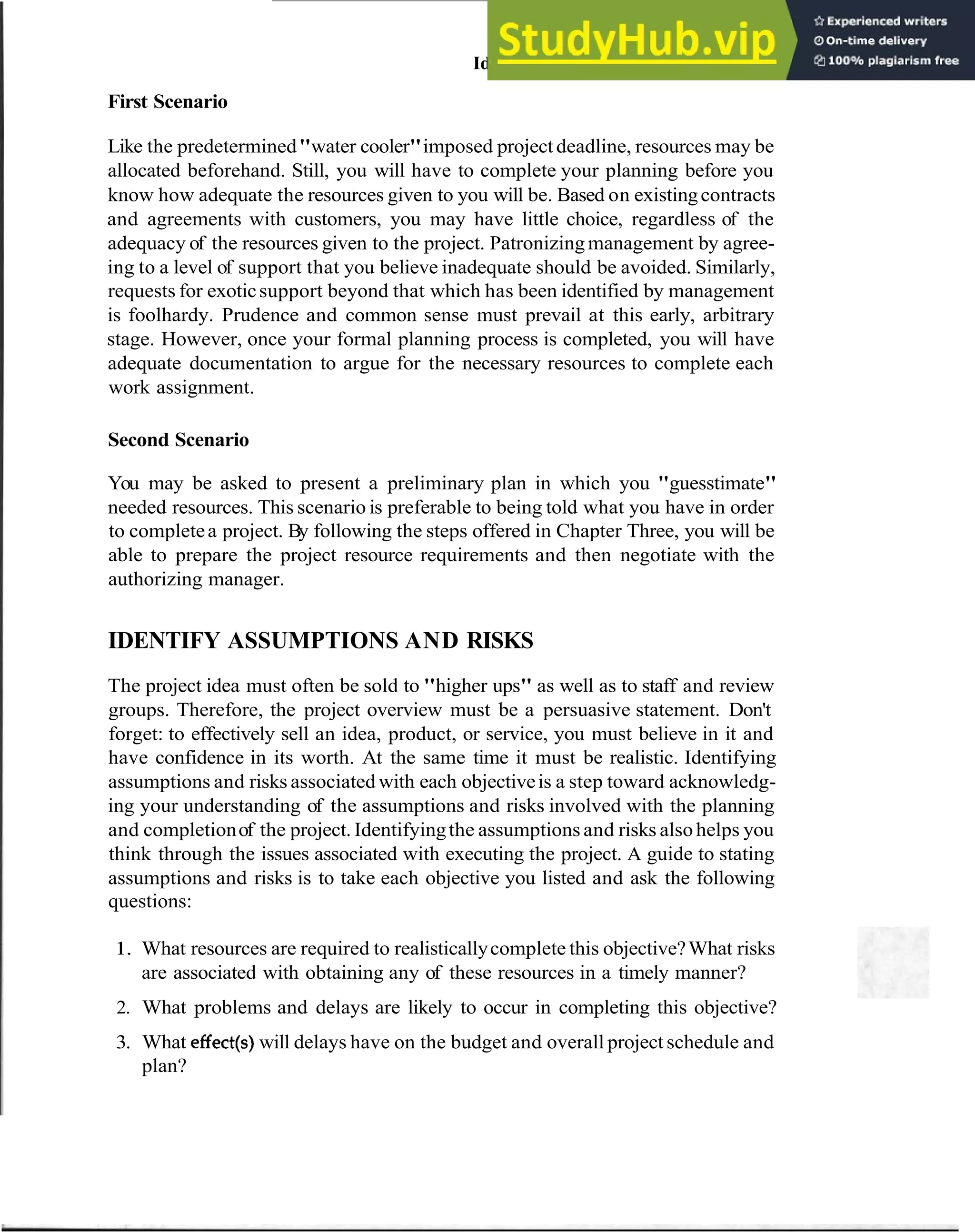

Figure 3-4 HIERARCHICALREPRESENTATIONOF THE CONFERENCEPLANNING WBS

1 CONFERENCE PLANNING 1

THEME MATERIALS SPEAKERS DATE PLACE LISTS BROCHURE REGISTER

e

f

i

'

f

)o,,,,,W]

MATERIALS BROCHURE BROCHURE

m

r

T

l

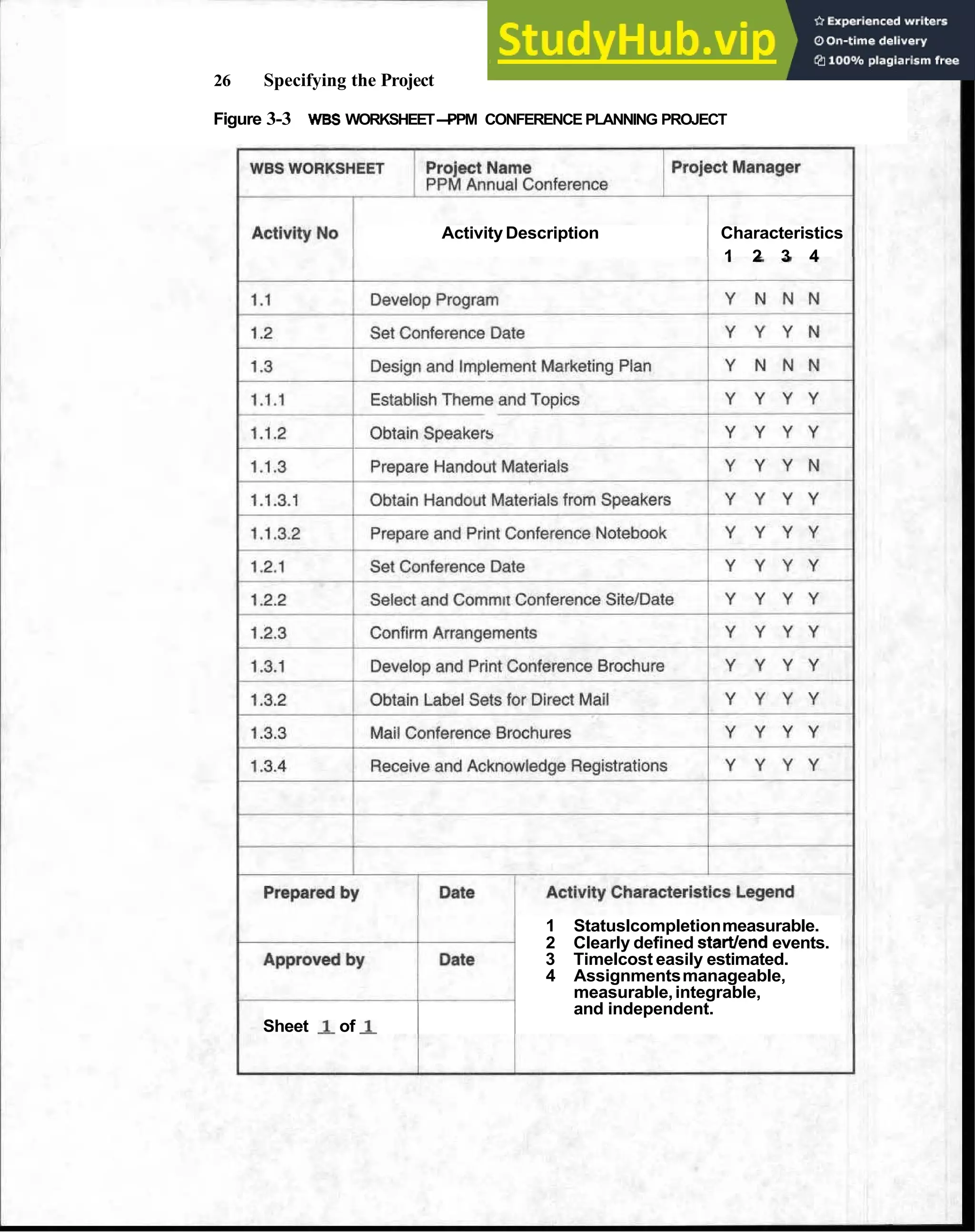

Uses of the Work Breakdown Structure

Just as the project overview was valuable during early planning activities, the

WBS is valuable during the more detailed planning activities and early imple-

mentation. One of its major uses is to provide a global-yet detailed-view of

the project. In this way, it will be the foundation for time, cost, and perform-

ance planning, and for control and reporting. As planning proceeds, the WBS

will be used to generate a network representation (discussed in Chapter Four)

of the project. This network will be the major control tool used by the project

manager to evaluate planned versus actual progress and to manage the

changes that will follow as a result of that evaluation.

The WBS is the easiest to learn and least error-prone technique we have

encountered for representing the many tasks that comprise even the simplest of

projects. It is a graphical representationthat is easily understood by those having

little familiarity with the details of the project. It is a tool that we will use in

Chapter Four to build the network of project activities. The W

B

S therefore serves

as an intermediate planning device.

There will be projects for which a network representation of a WBS may

seem too difficult to generate. In those cases we have found it helpful to

consider other approaches to defining the WBS. For example, the project may

be decomposed by functional business unit, by geographic location, by depart-

ment, according to the skills needed, or based on equipment or material avail-

ability. These alternatives may work in cases where the more straightforward

hierarchical approach fails. The best advice we can give is to think creatively

when developing the WBS.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-phaseprojectmanagement-230805214544-55cdbcc8/75/5-PHASE-PROJECT-MANAGEMENT-41-2048.jpg)