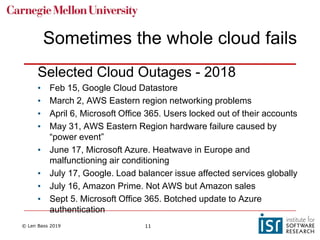

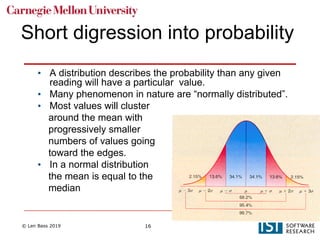

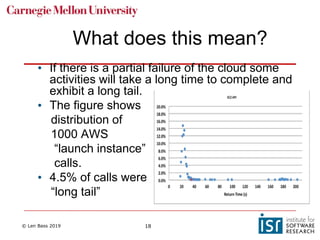

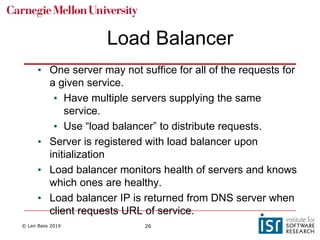

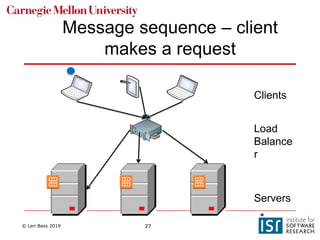

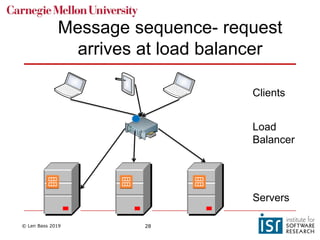

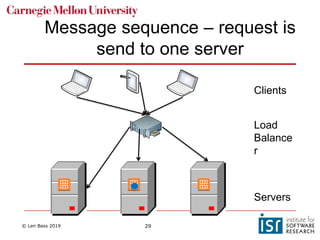

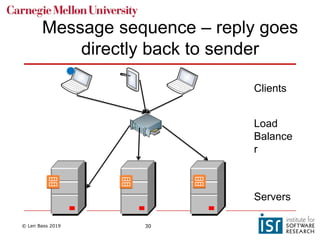

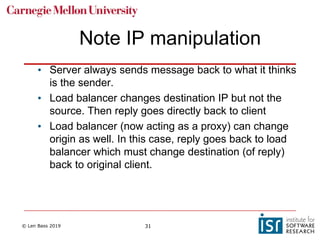

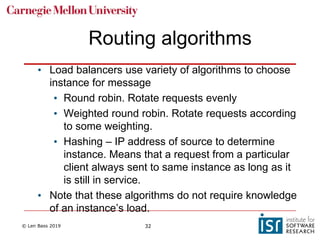

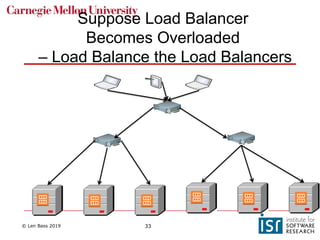

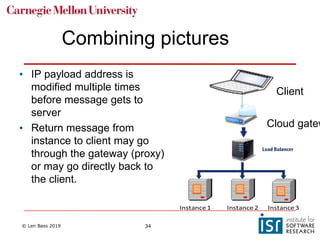

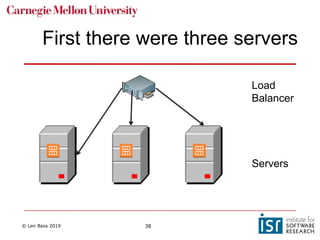

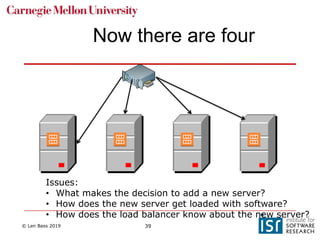

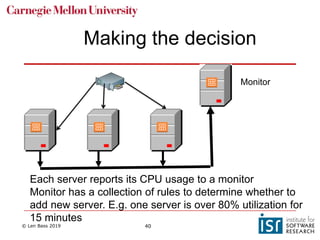

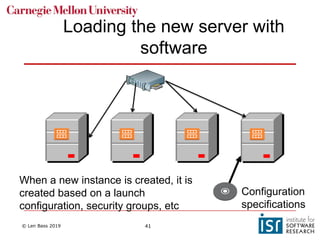

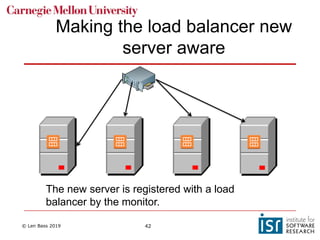

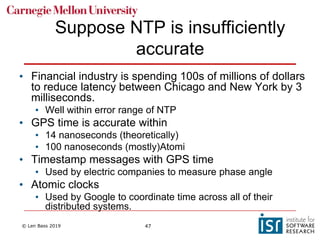

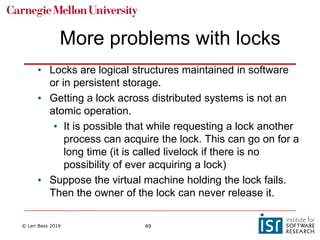

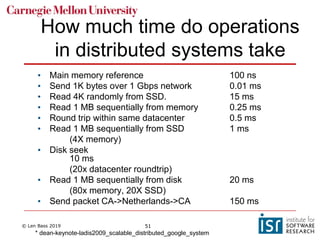

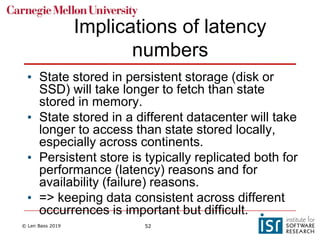

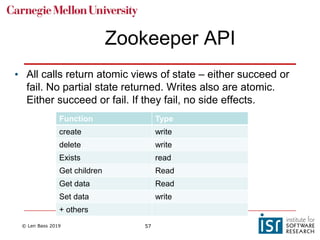

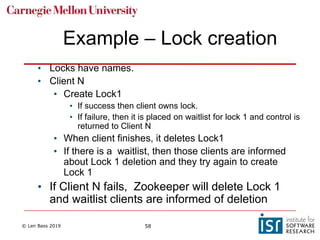

The document discusses distributed systems and failures in cloud computing environments. It describes how cloud providers organize their data centers across regions and availability zones. When failures occur, they can impact the entire cloud or just parts of it. The long tail is discussed as a phenomenon where some operations take much longer than average to complete. Techniques for dealing with failures include retrying operations, instantiating redundant services, and implementing circuit breakers. Load balancers help distribute traffic across multiple servers. Autoscaling allows adding more servers when load increases. Achieving atomic operations is challenging in distributed systems due to latency and potential component failures. Consensus algorithms like Paxos can help synchronize data across servers in a consistent manner.