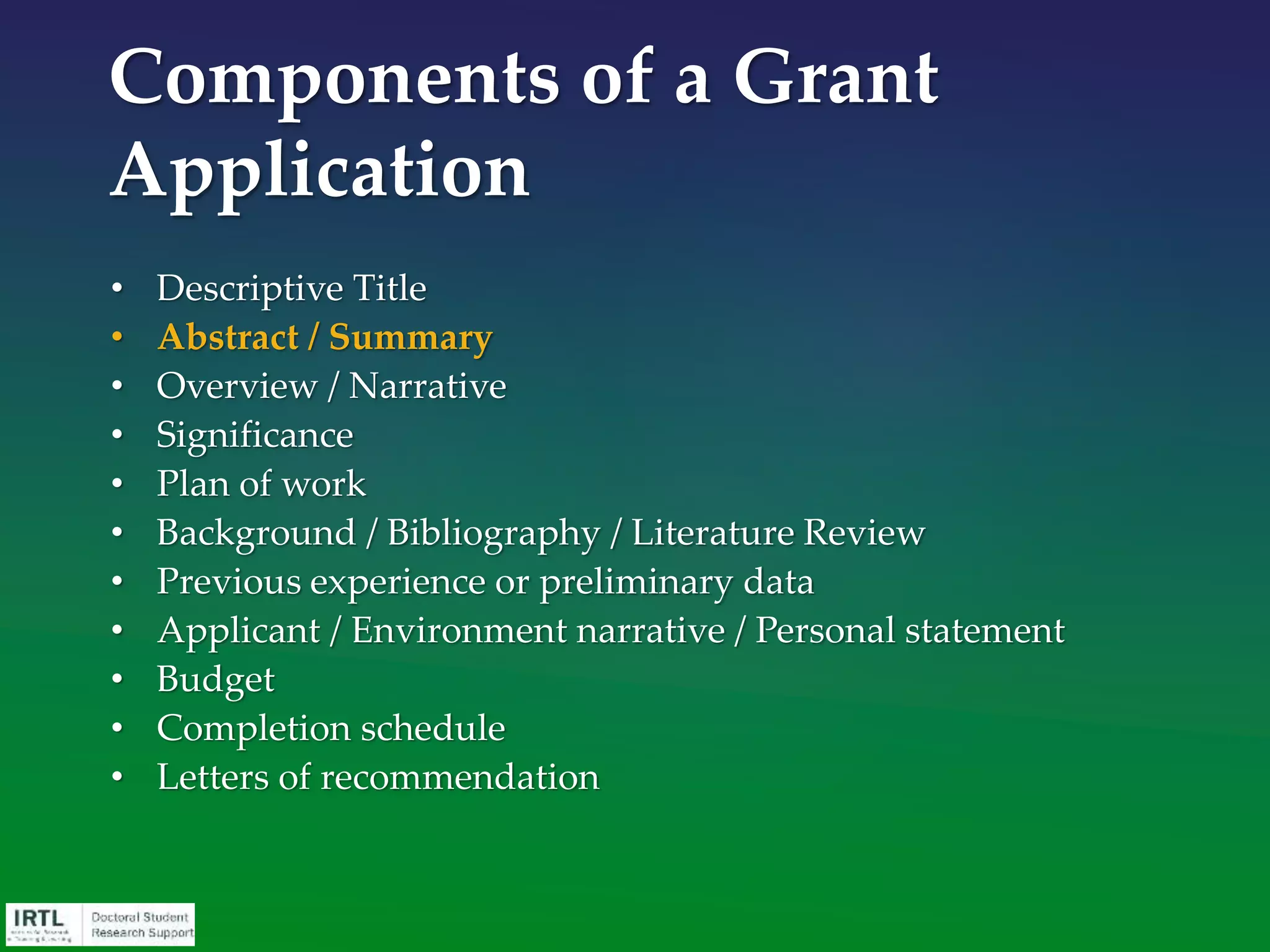

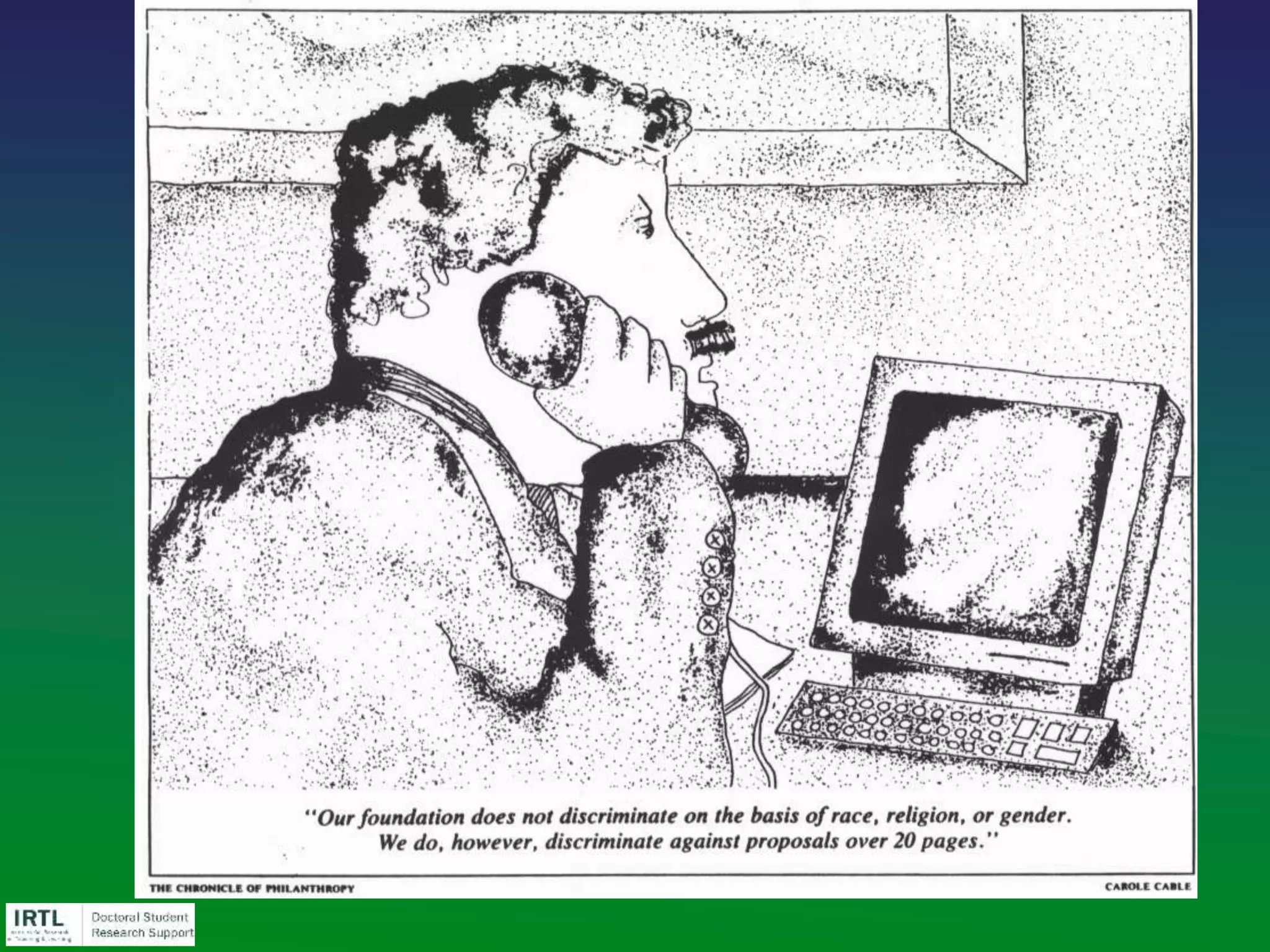

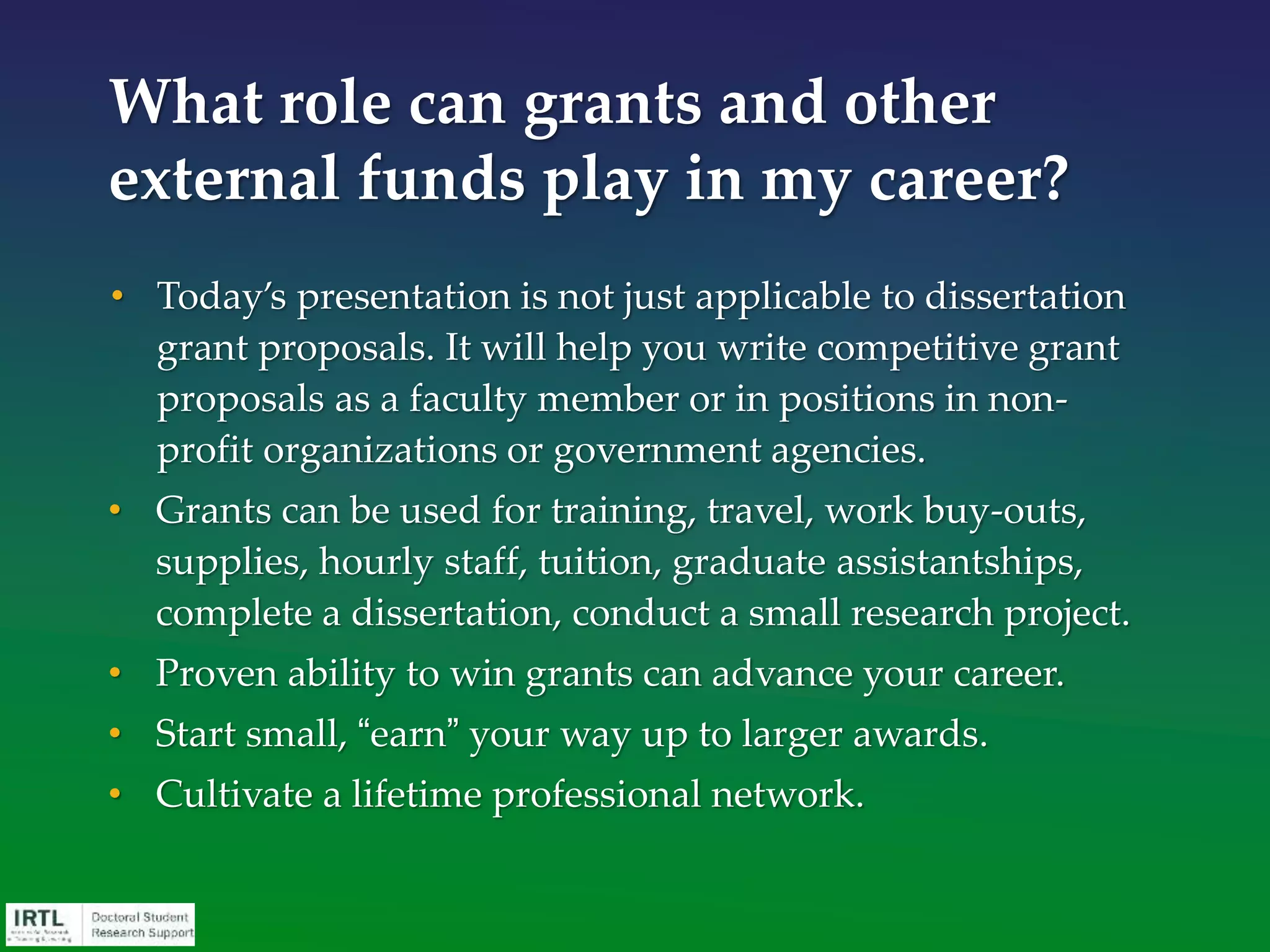

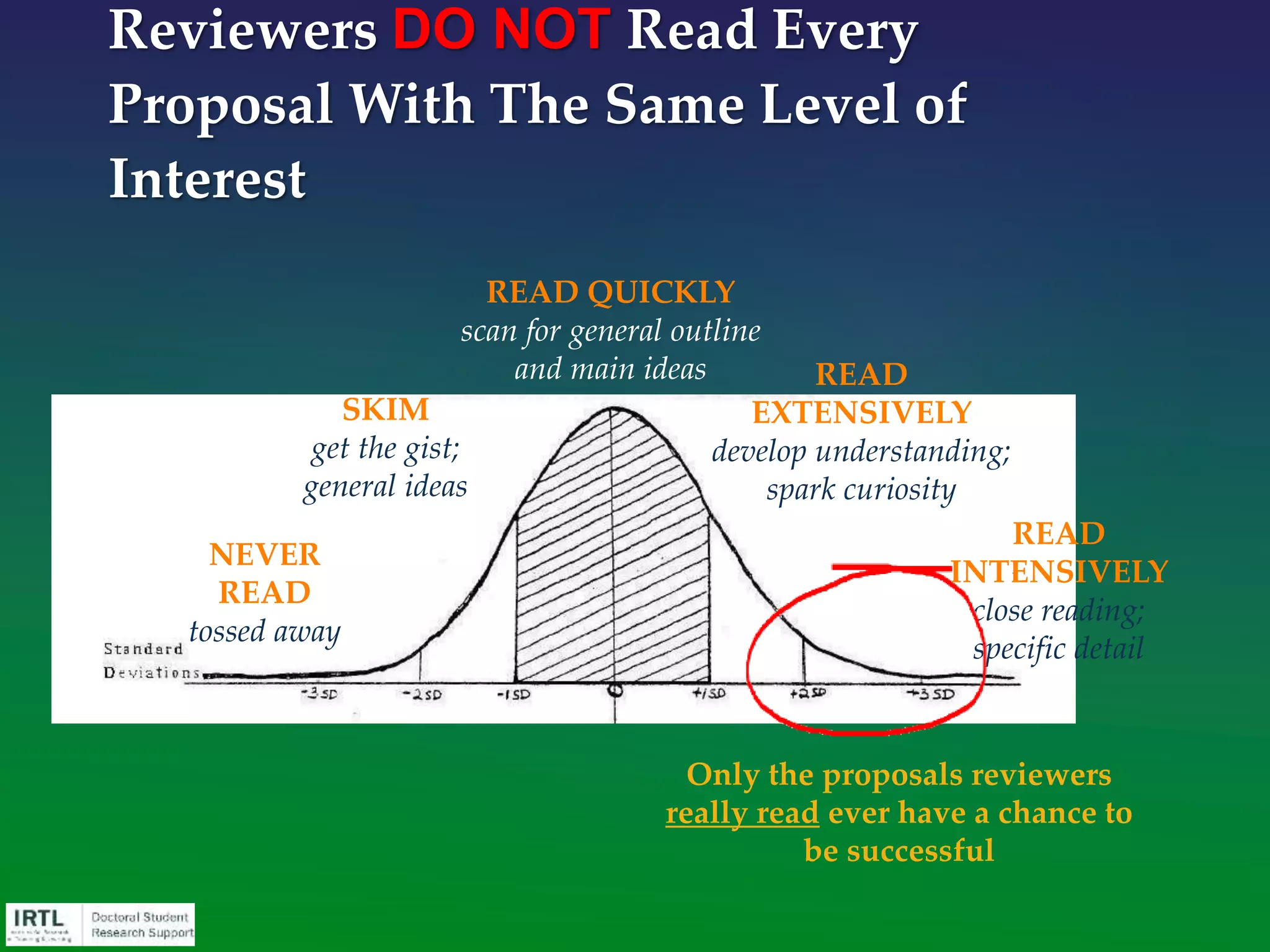

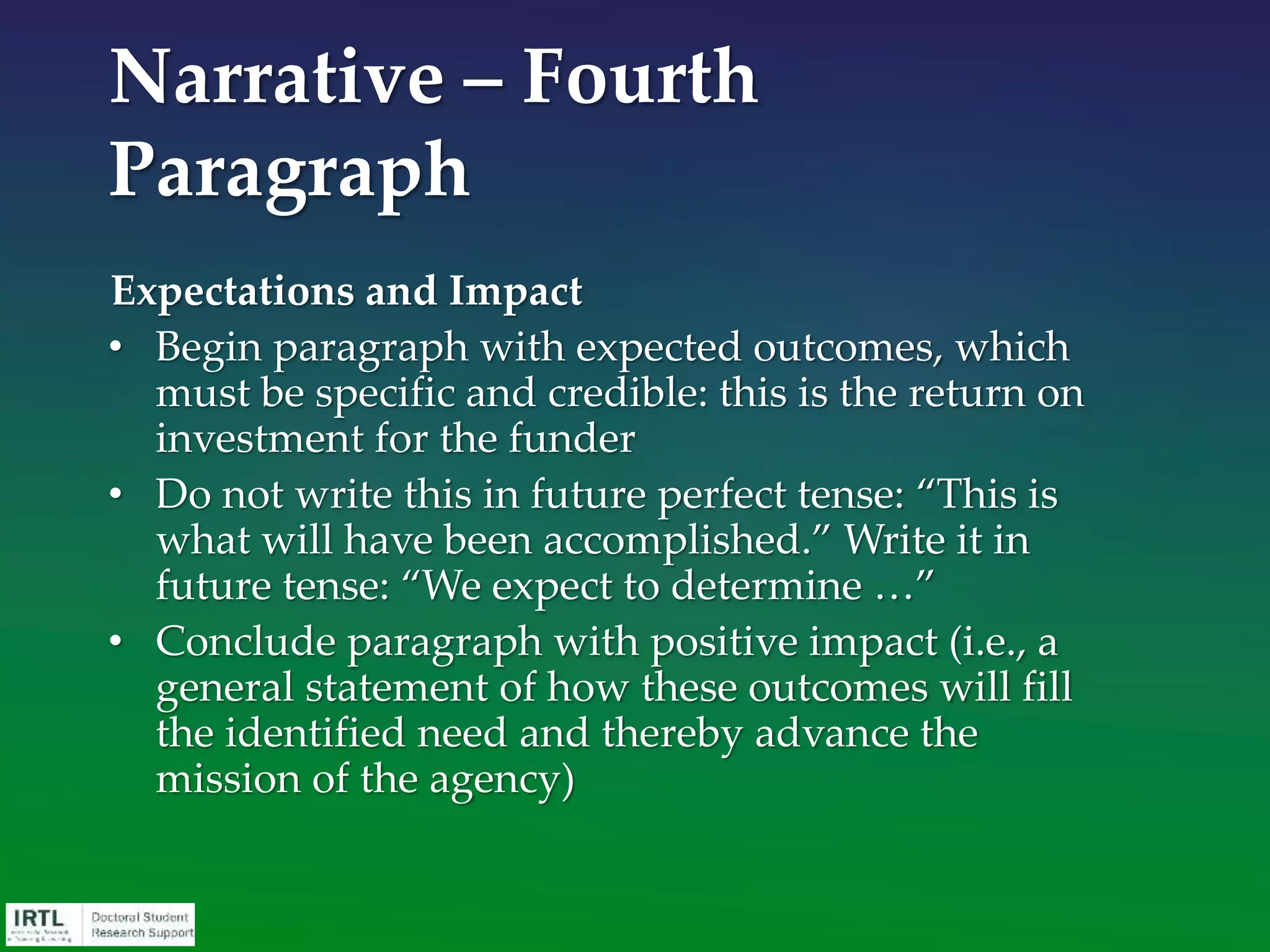

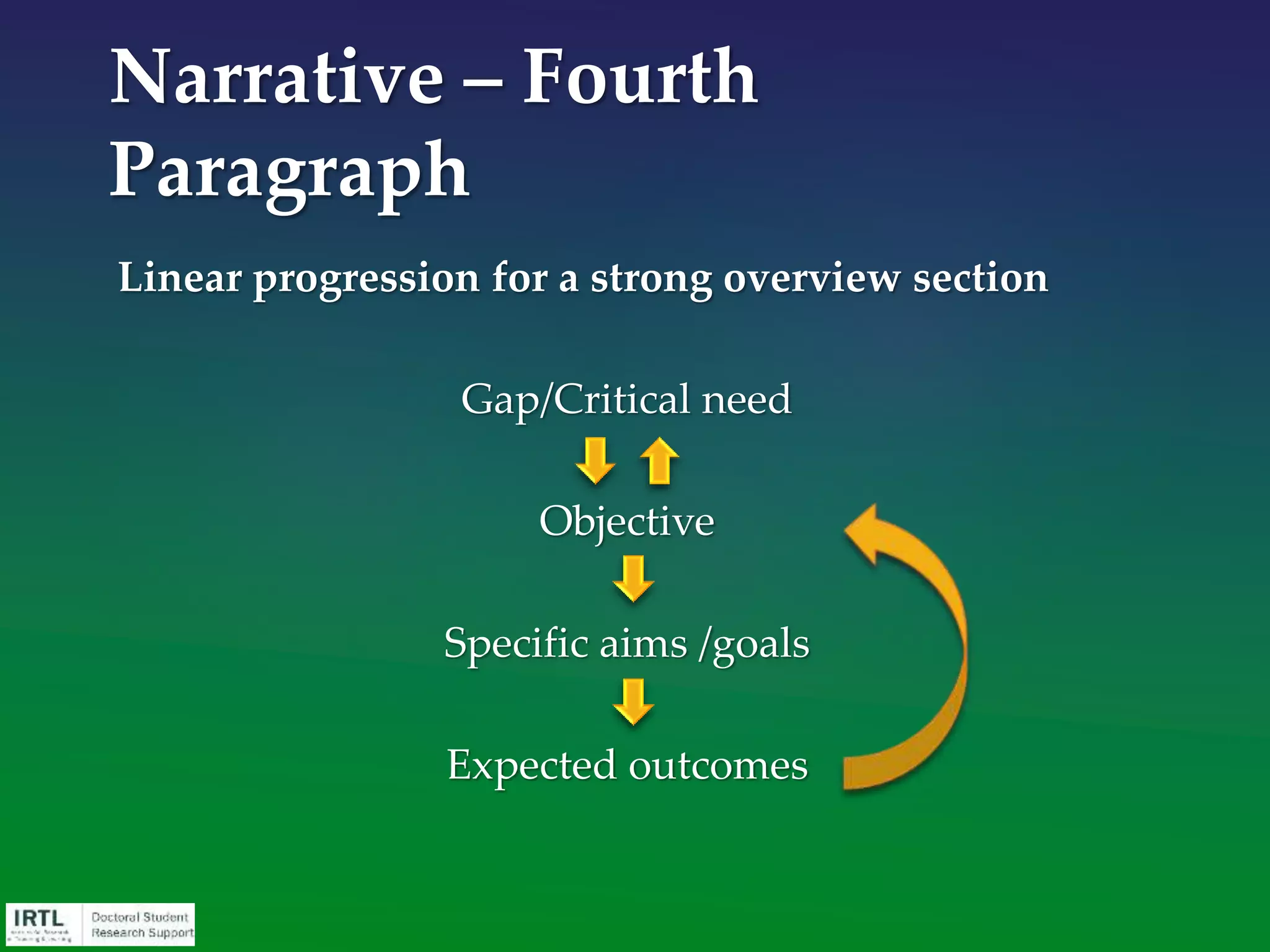

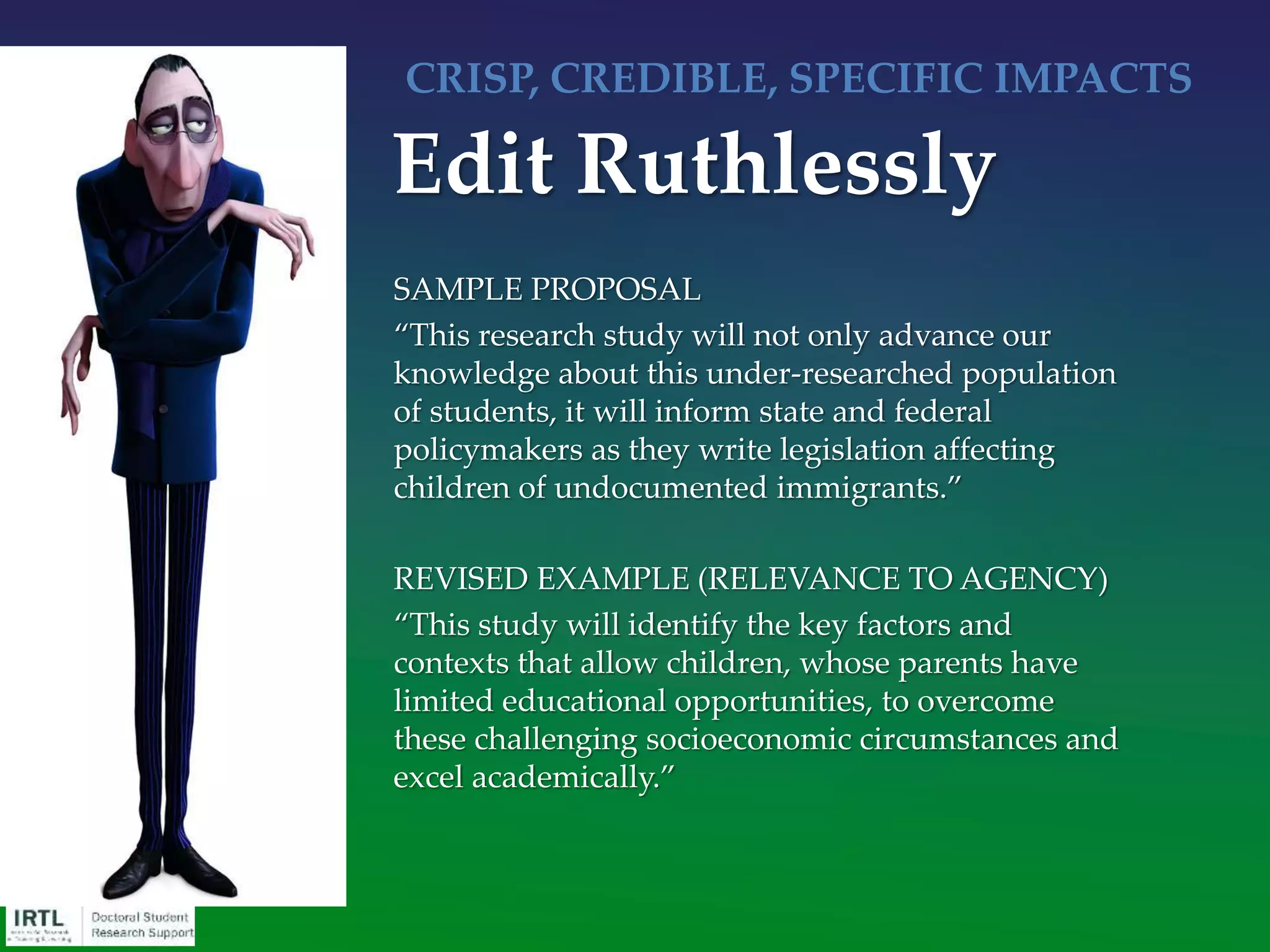

The document is a workshop guide for doctoral students on writing competitive grant applications, emphasizing the importance of understanding grant writing components and funding sources. It provides tips on proposal framing, effective communication, and strategies to increase the likelihood of gaining funding. Key advice includes identifying a compelling need and solution, and tailoring proposals to align with funding agency missions.

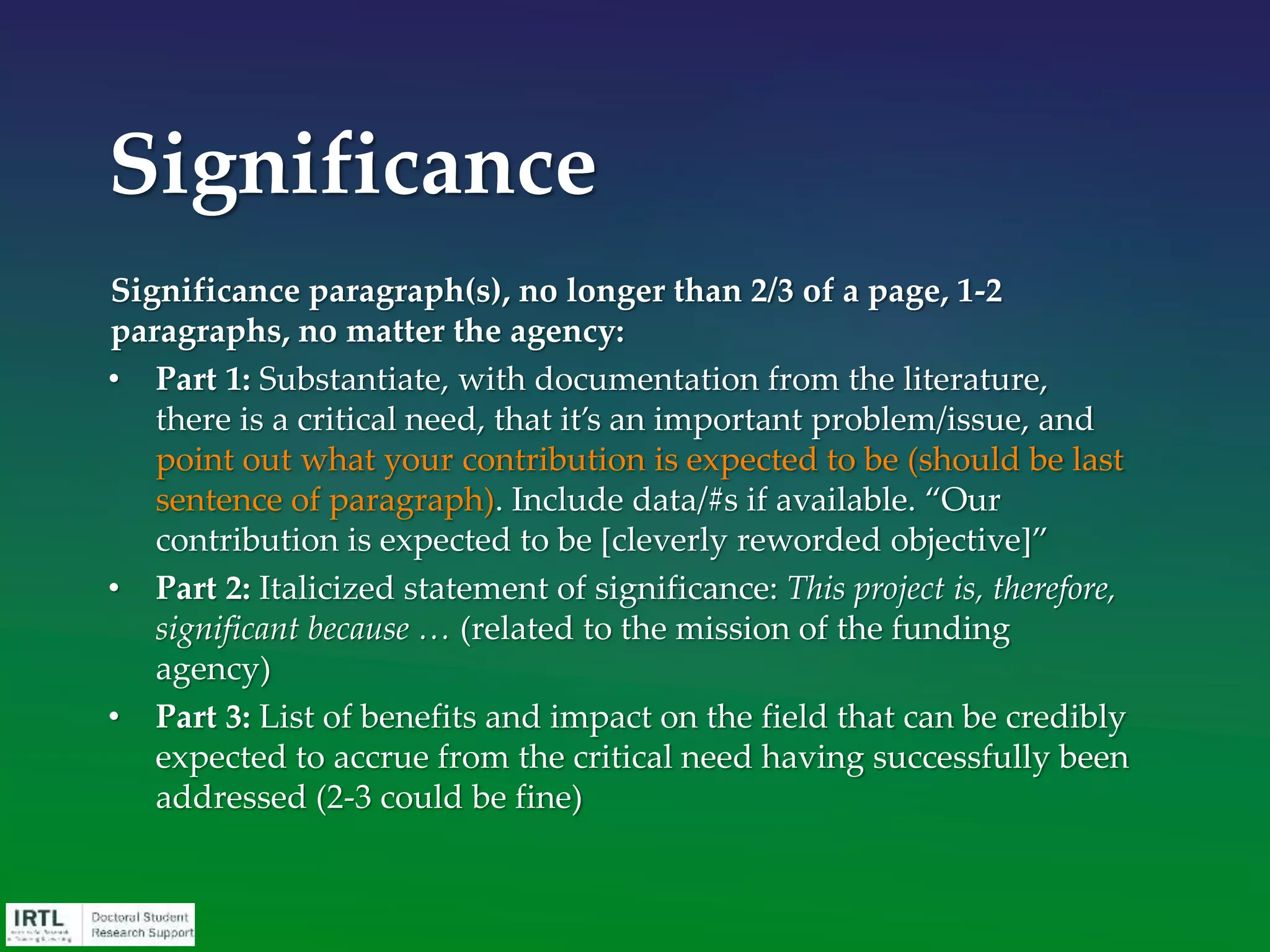

![Significance paragraph(s), no longer than 2/3 of a page, 1-2

paragraphs, no matter the agency:

• Part 1: Substantiate, with documentation from the literature,

there is a critical need, that it’s an important problem/issue, and

point out what your contribution is expected to be (should be last

sentence of paragraph). Include data/#s if available. “Our

contribution is expected to be [cleverly reworded objective]”

• Part 2: Italicized statement of significance: This project is, therefore,

significant because … (related to the mission of the funding

agency)

• Part 3: List of benefits and impact on the field that can be credibly

expected to accrue from the critical need having successfully been

addressed (2-3 could be fine)

Significance](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2015-03grantwritingworkshop-150401120921-conversion-gate01/75/2015-03GrantWriting-103-2048.jpg)