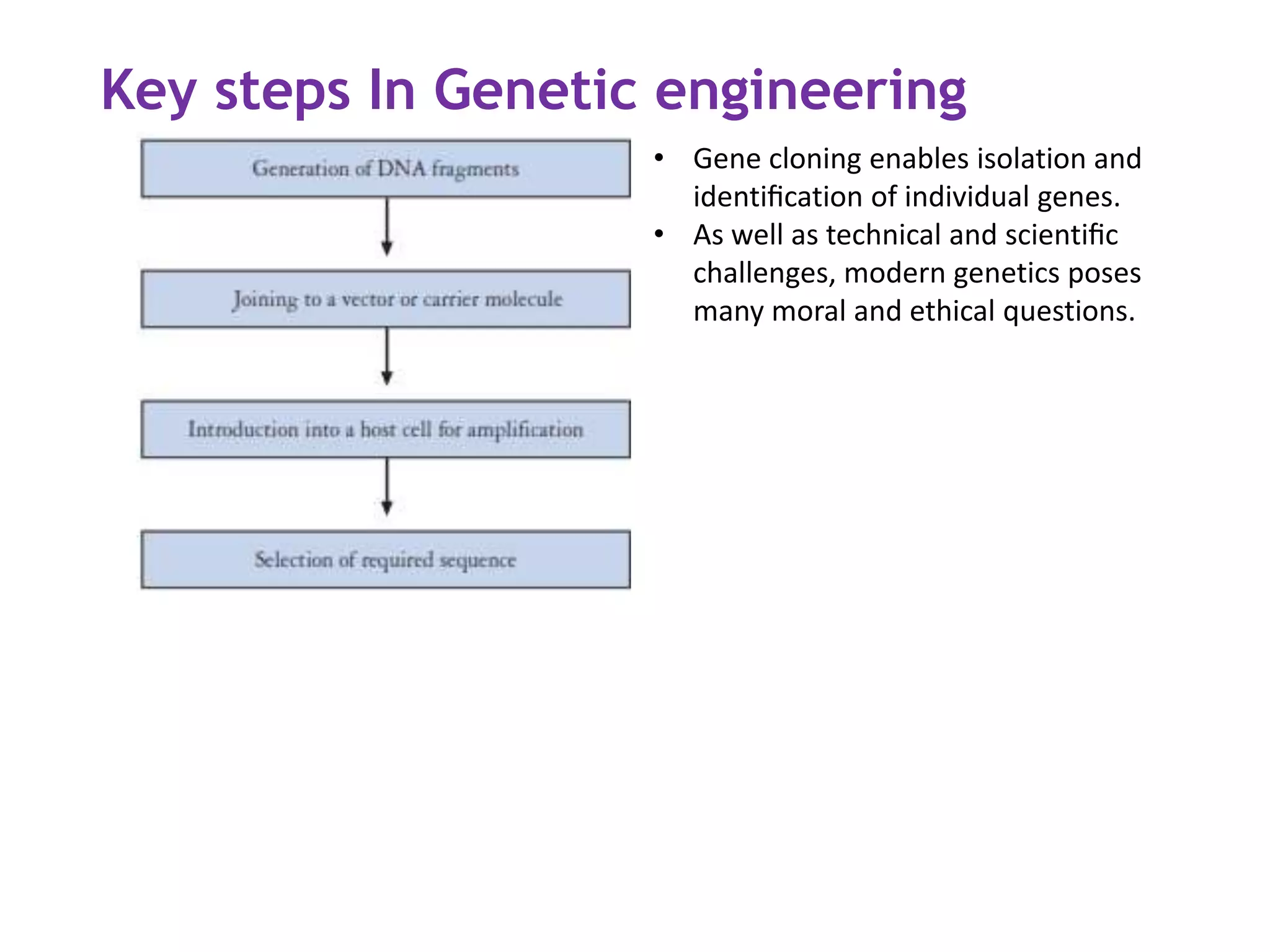

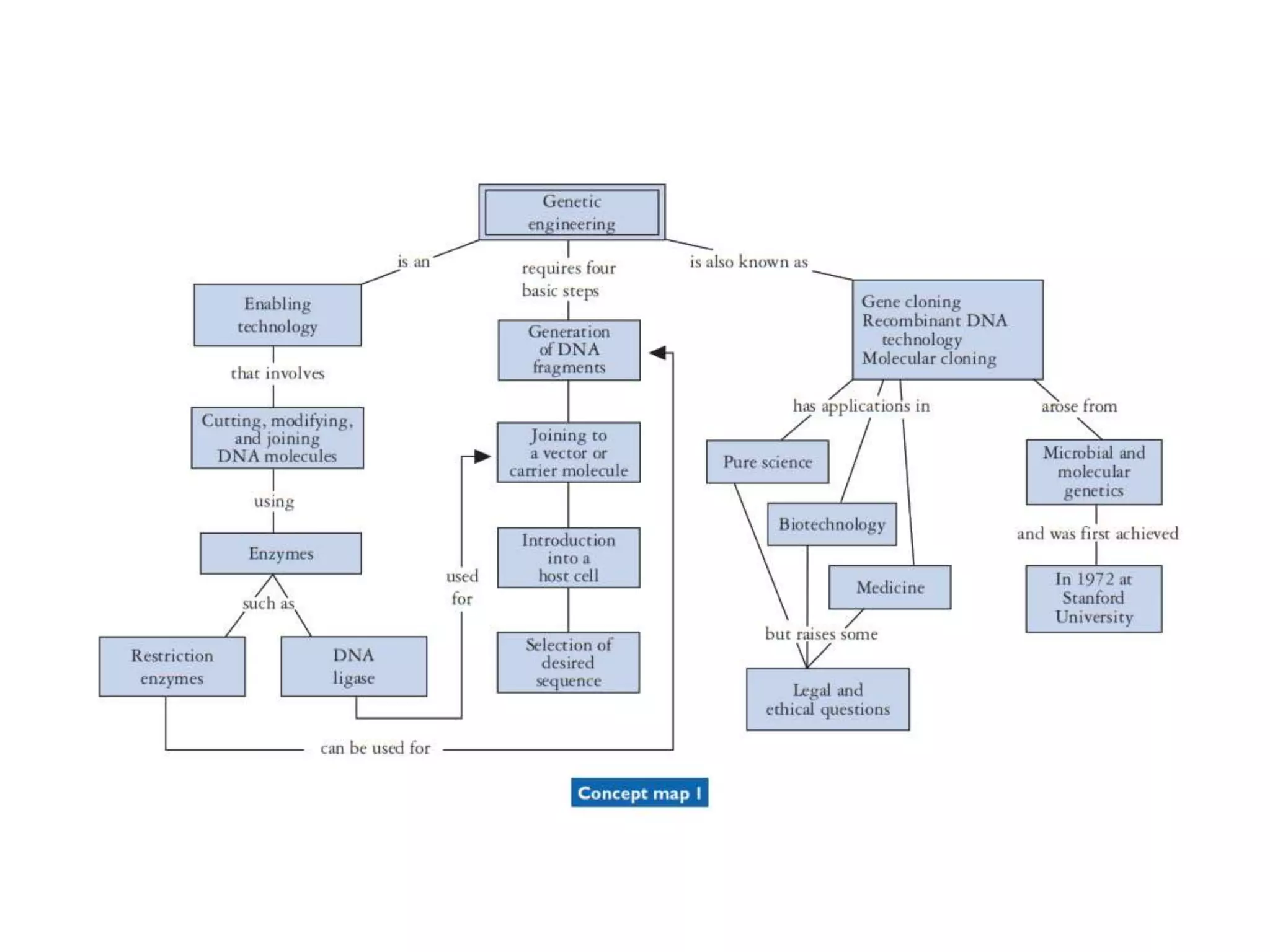

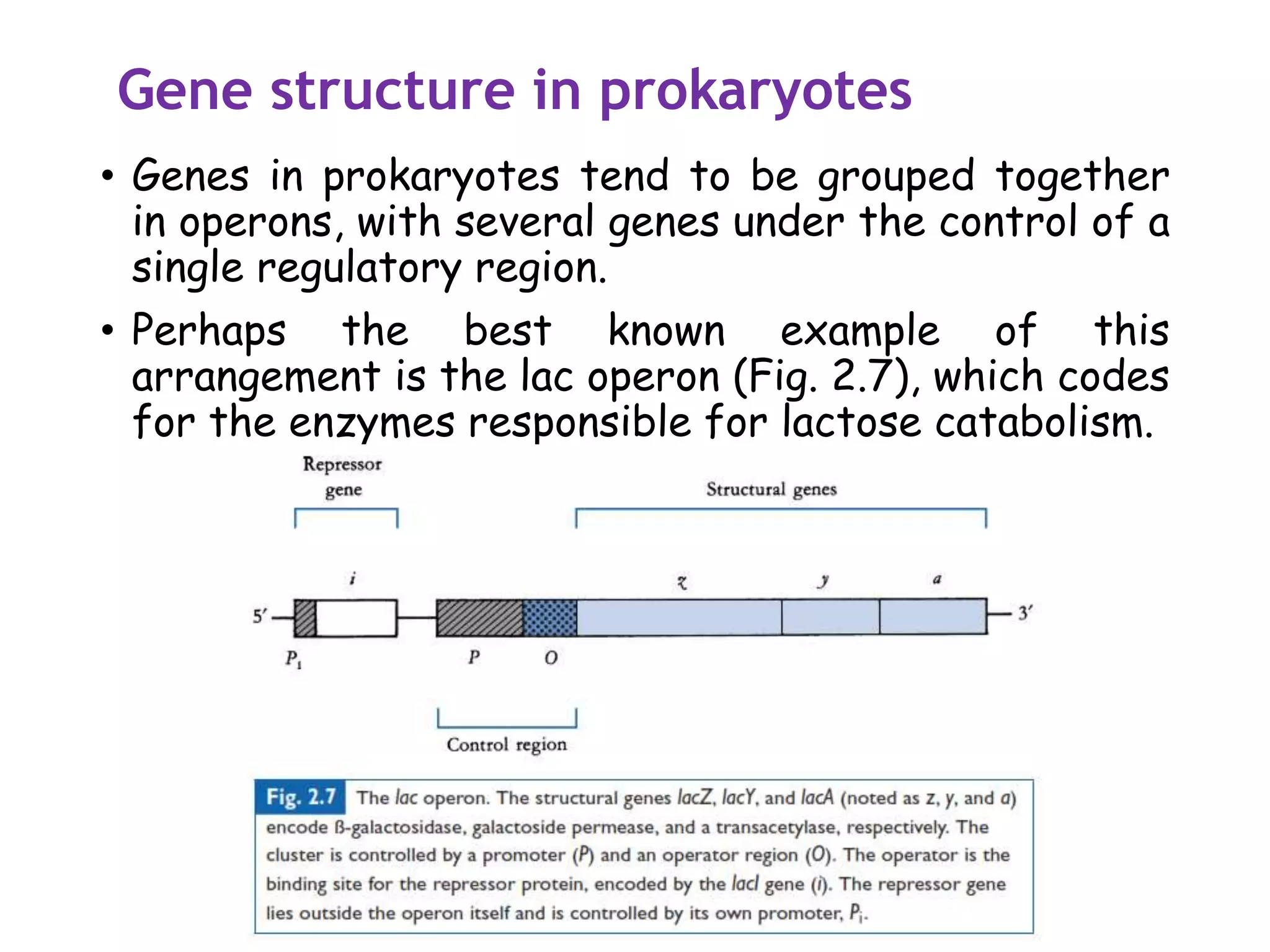

The document provides a comprehensive overview of genetic engineering, covering its definitions, historical developments, and key techniques including gene cloning, restriction enzymes, and DNA ligases. It explains the differences in gene structure and function between prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and outlines the intricacies of gene expression and regulation. Additionally, it discusses the ethical considerations surrounding genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and presents the roles of various enzymes involved in DNA manipulation.

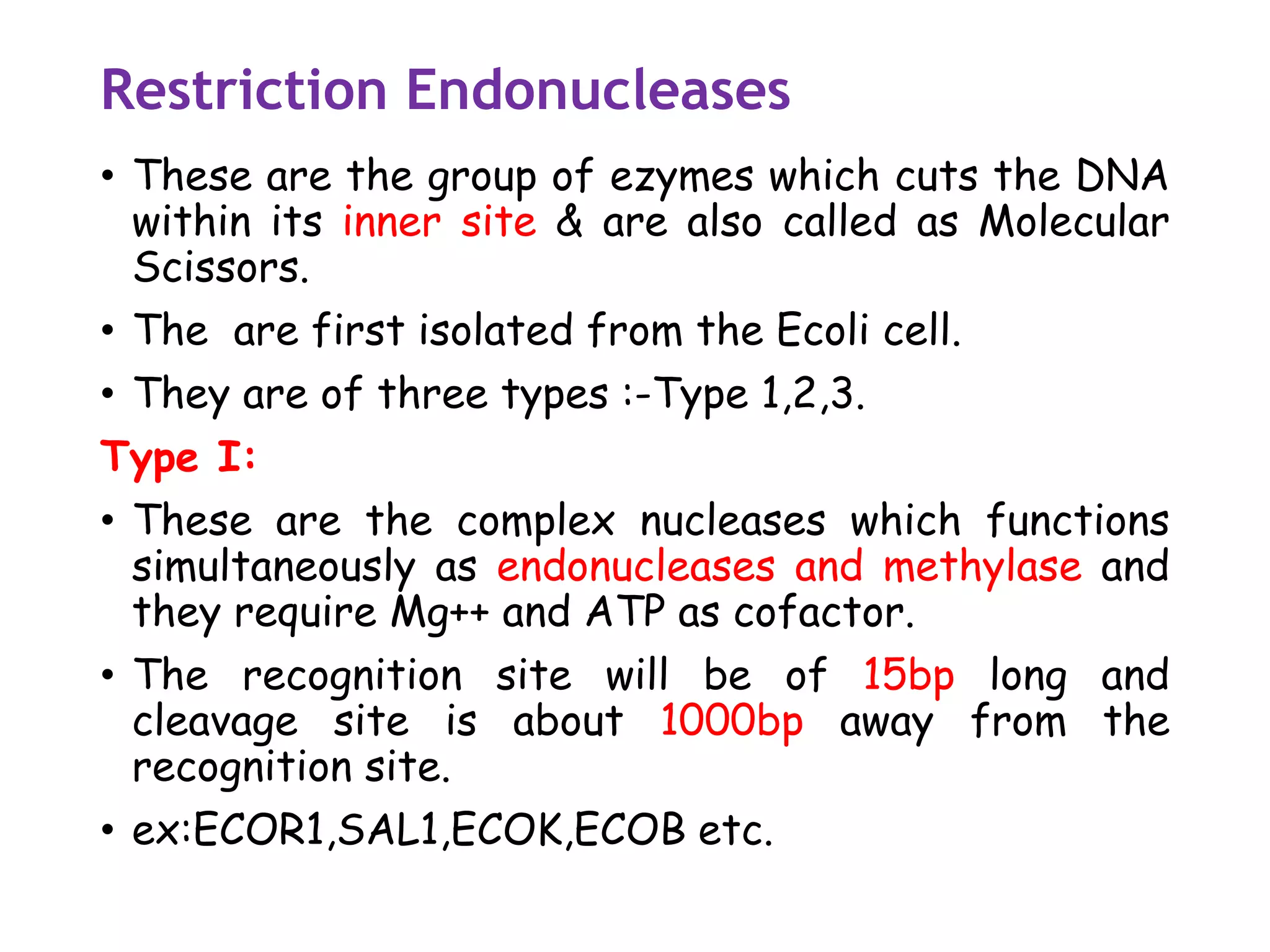

![STICKY END CUTTERS

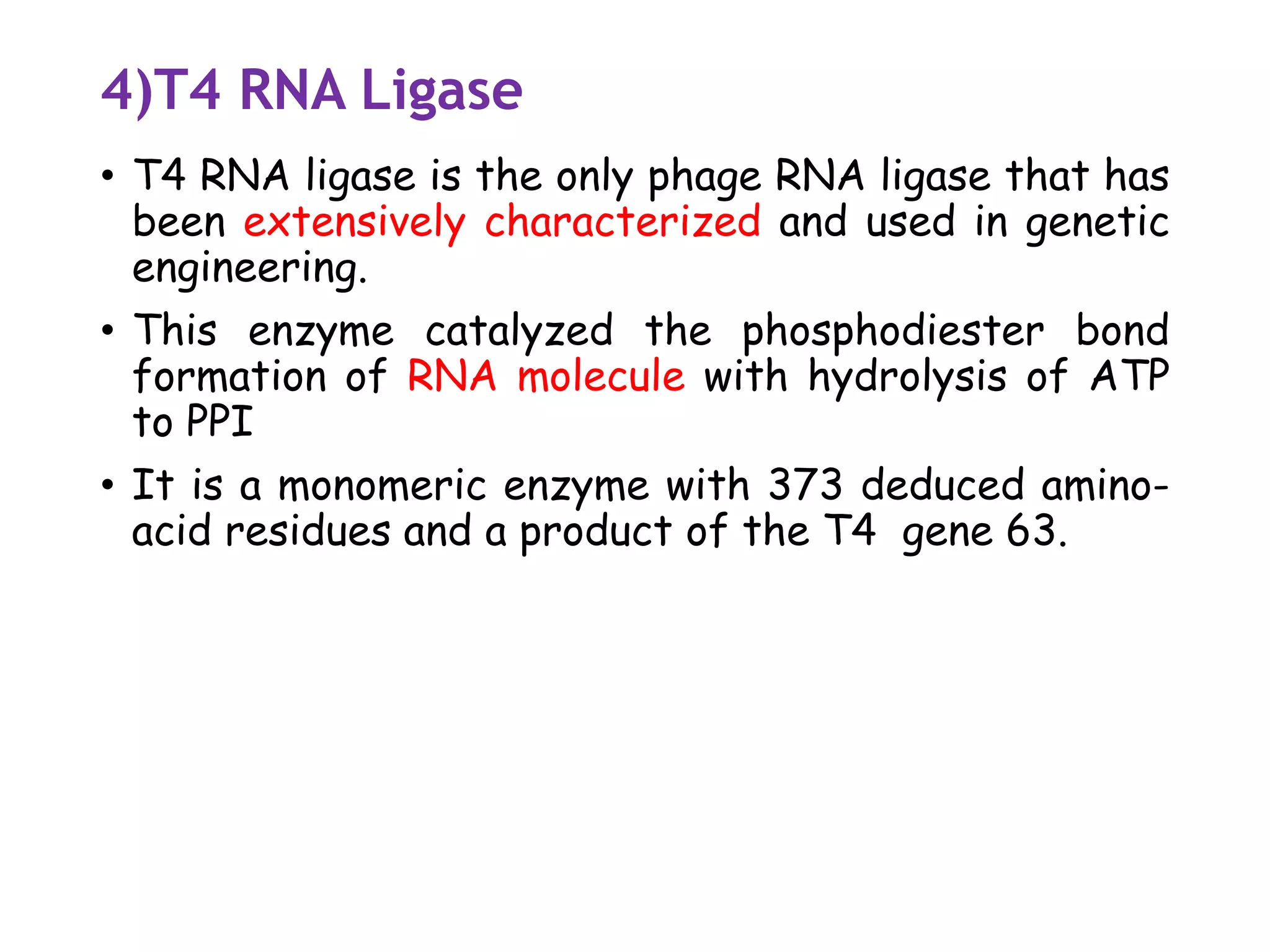

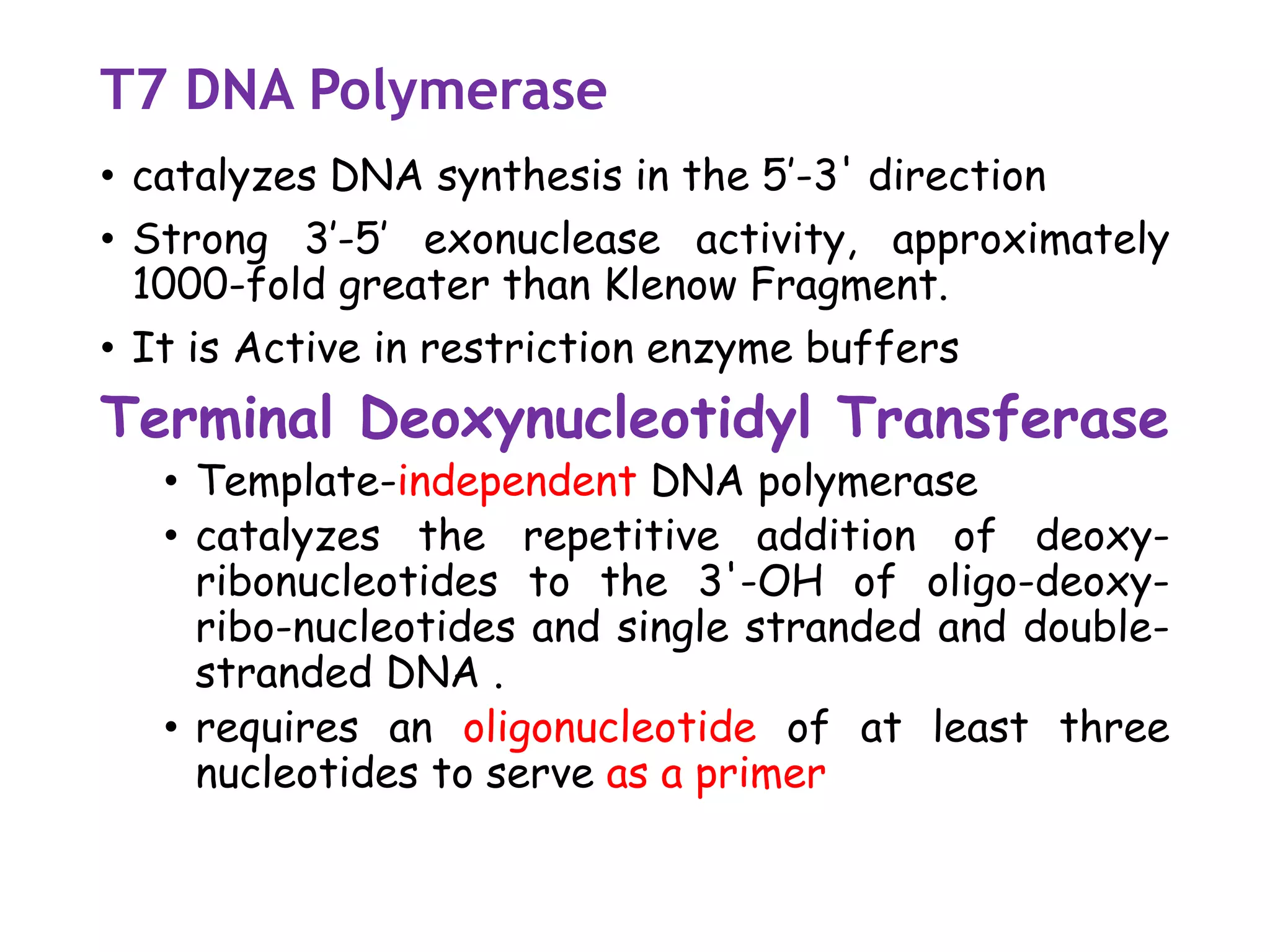

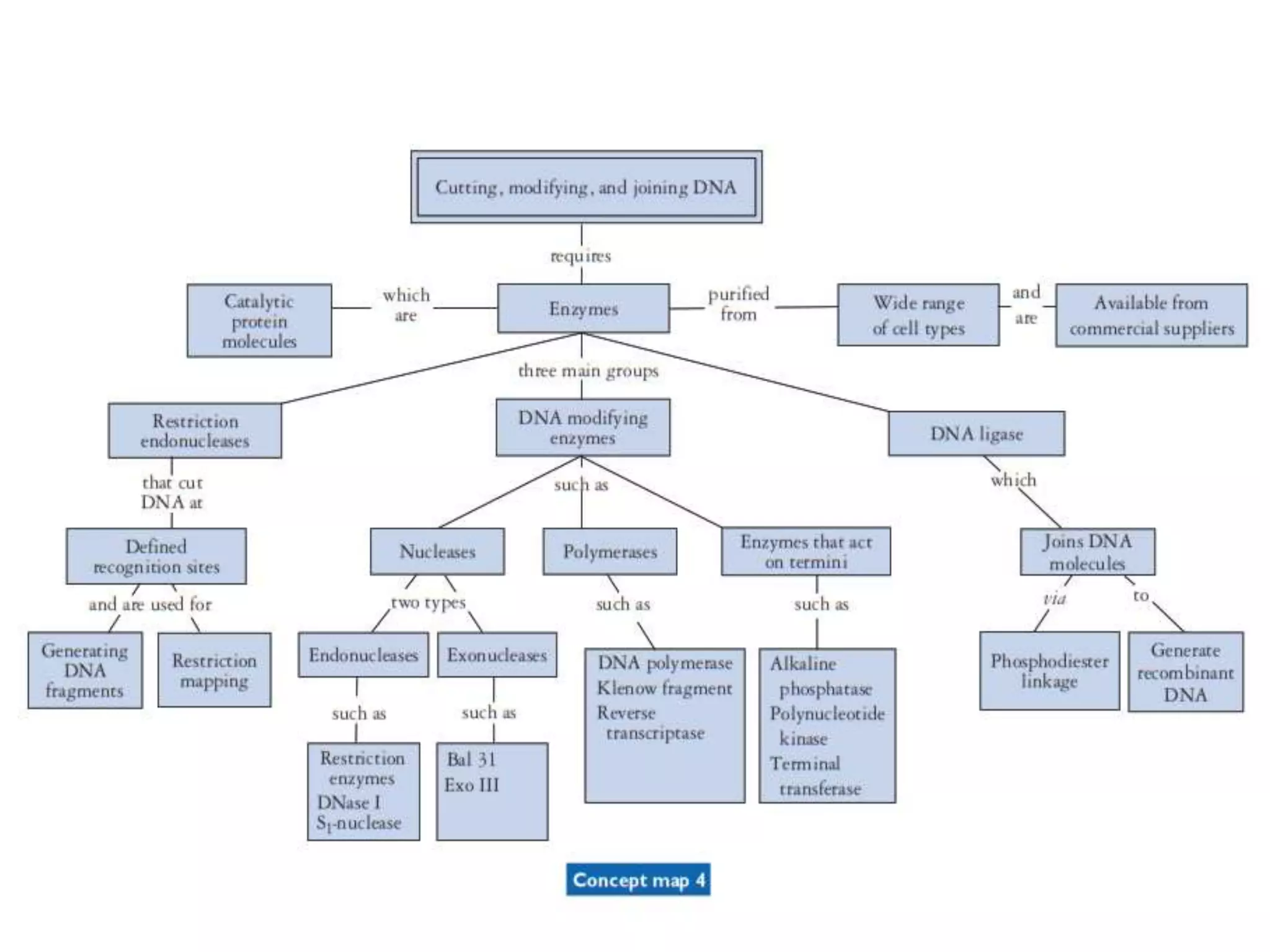

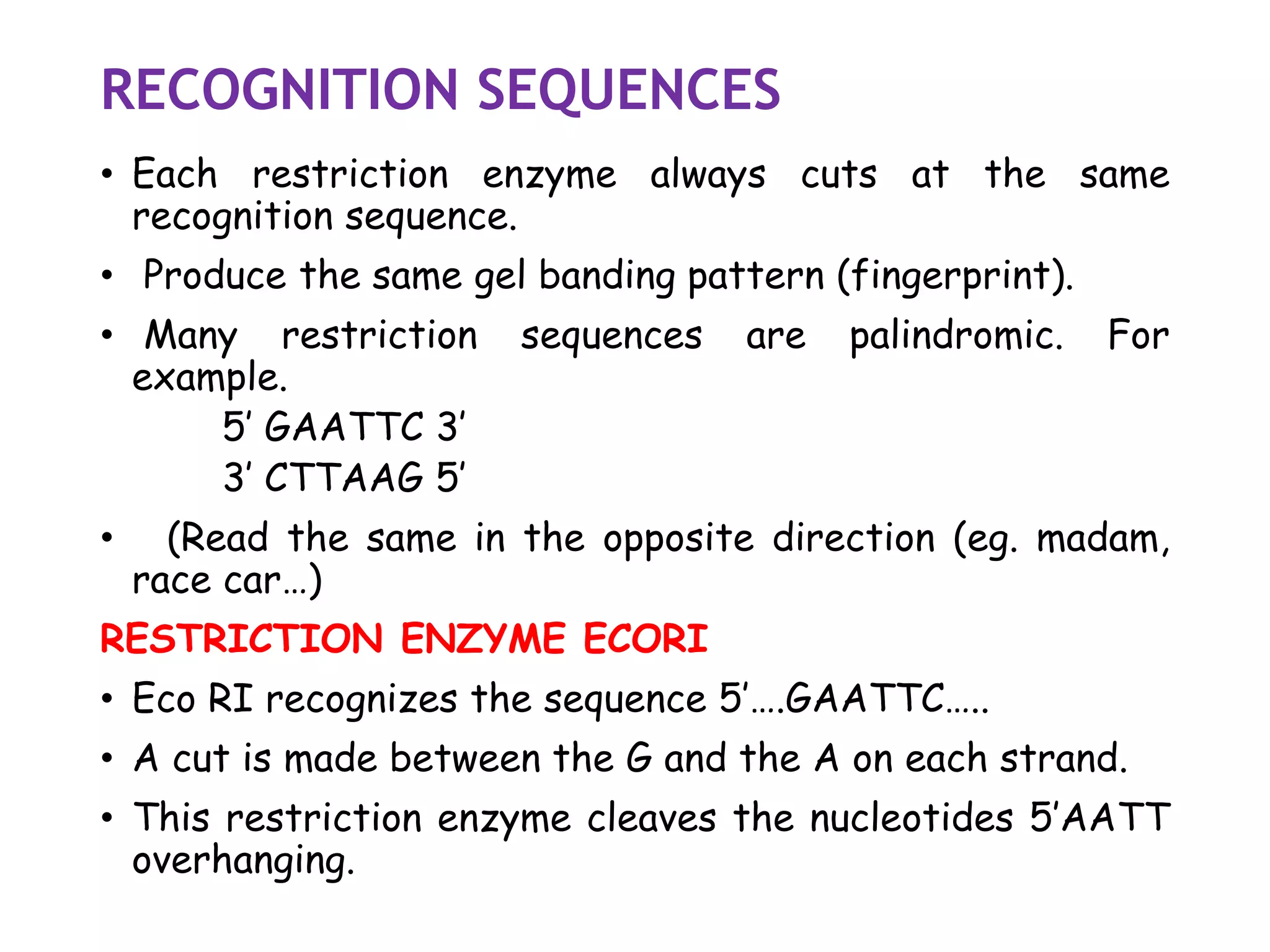

Most restriction enzymes make staggered cuts.

Staggered cuts produce single stranded

"sticky-ends".

o

o

DNA from different sources

easily because of sticky-end

can be spliced

overhangs.

o

Hindlll

•

A - A - T - T - C T 7

I

IEcoRI I I I I

[ I ] ! + 1 ' ! p

( I- + C - T- T- A - A - G •

t](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-200312055538/75/1-introduction-to-genetic-engineering-and-restriction-enzymes-35-2048.jpg)

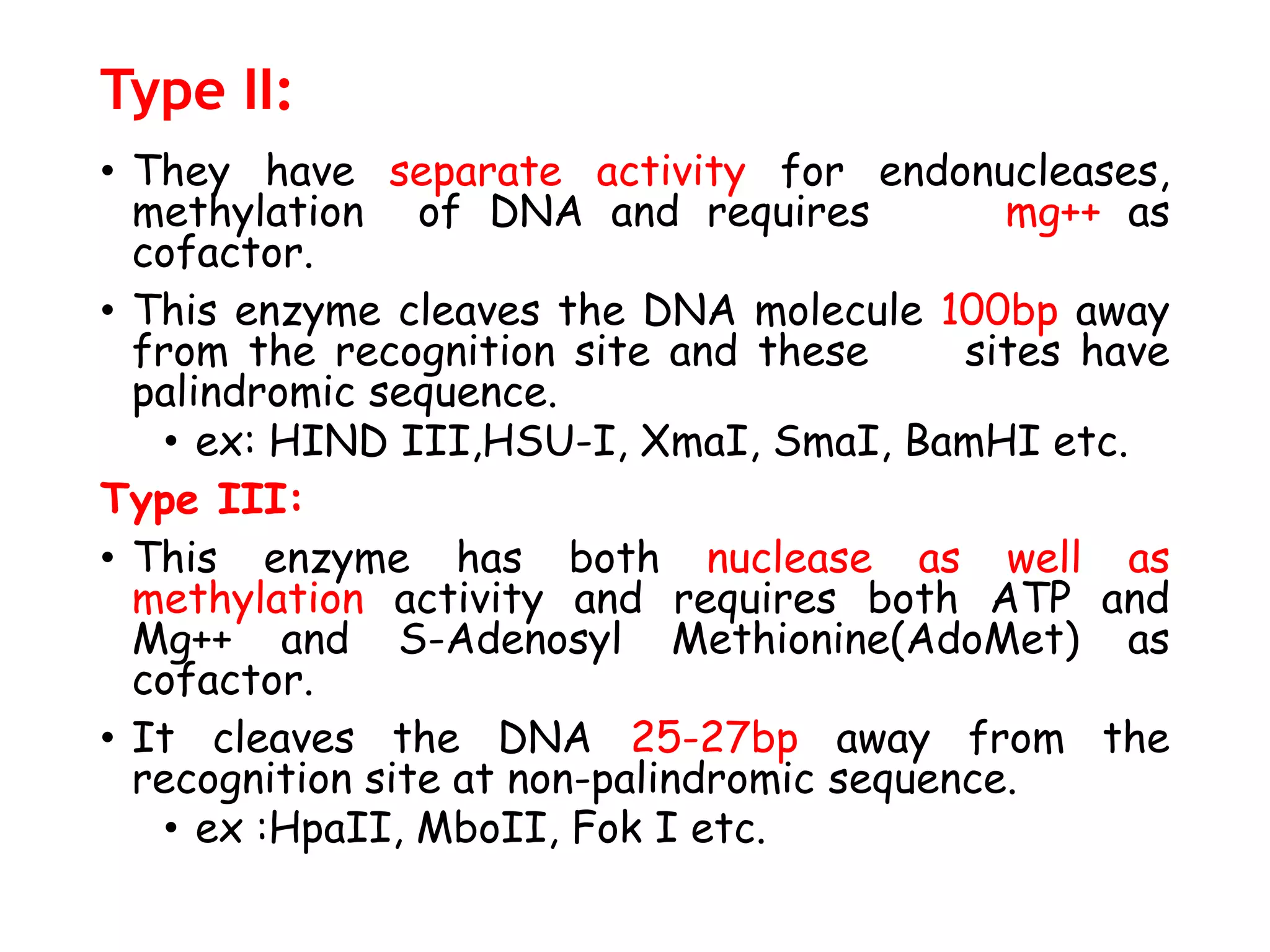

![BLUNT END CUTTERS

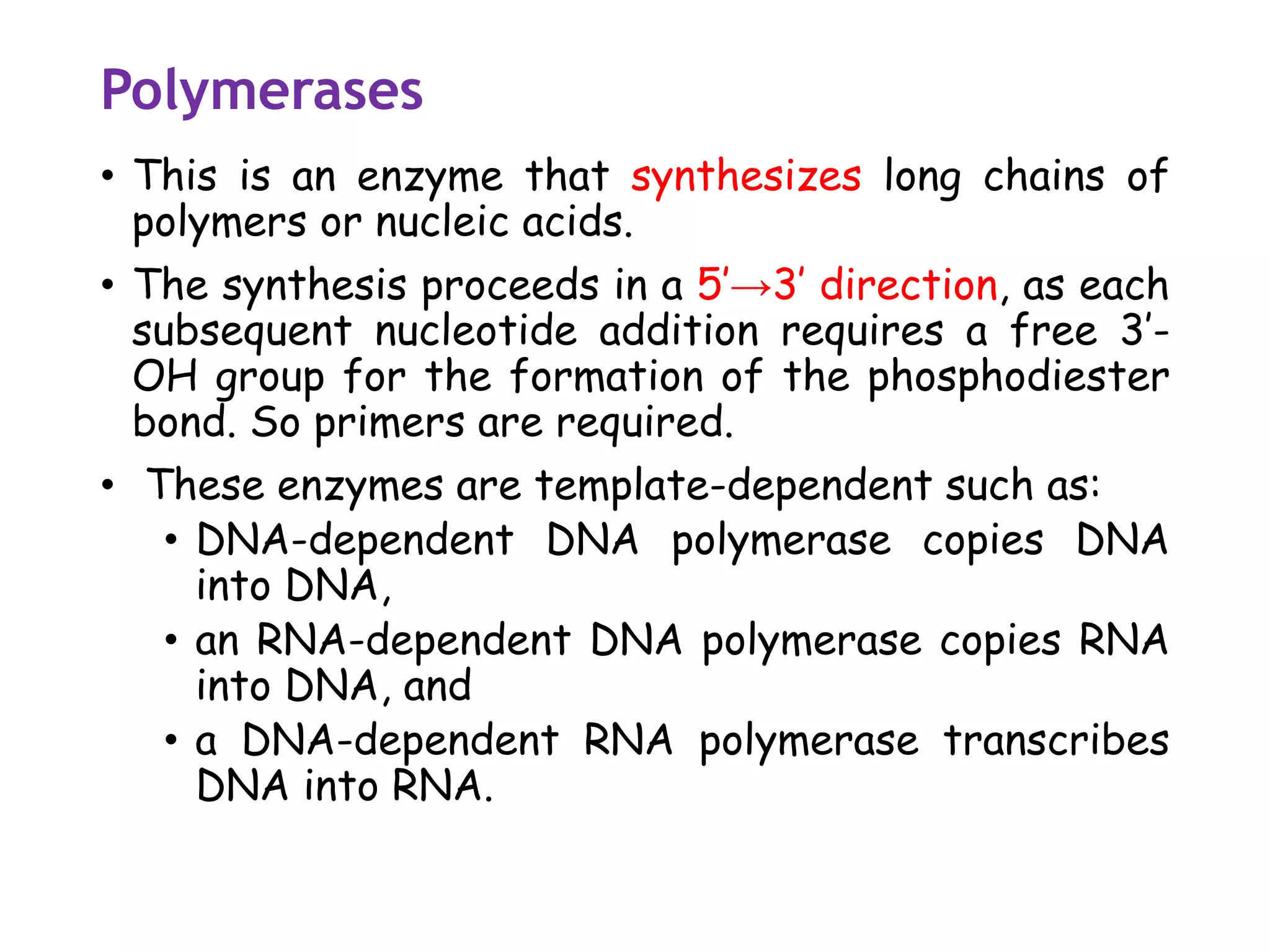

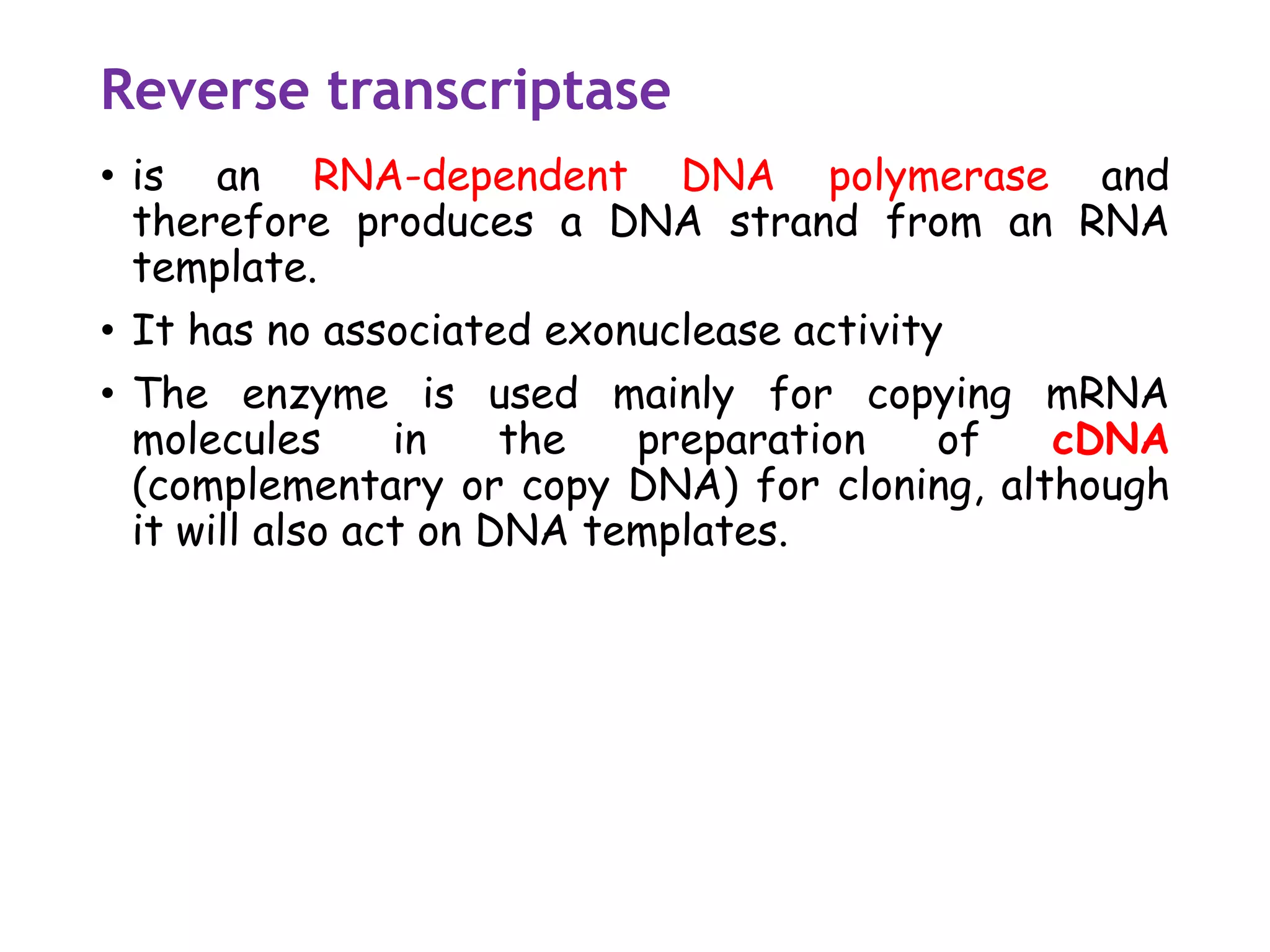

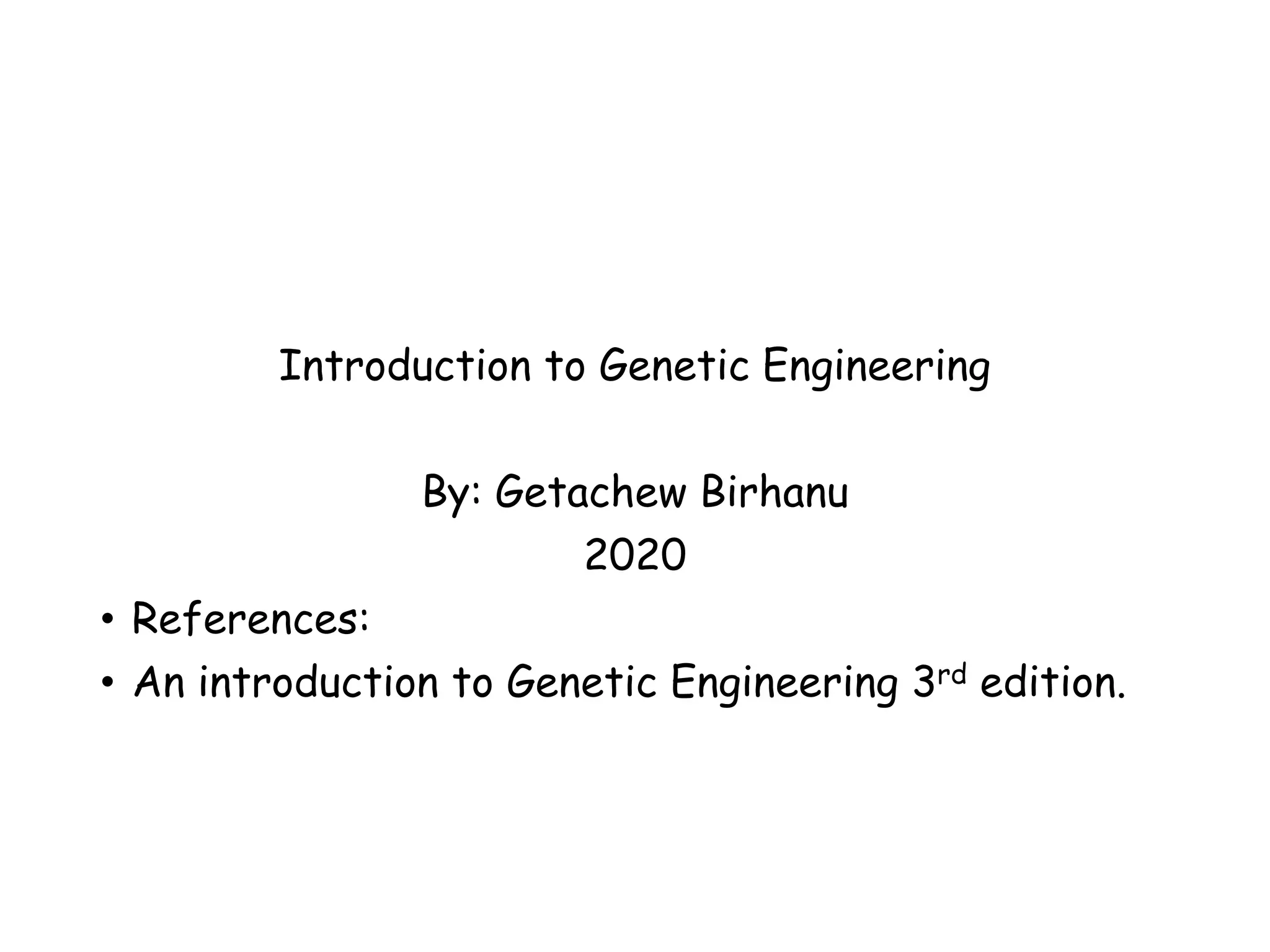

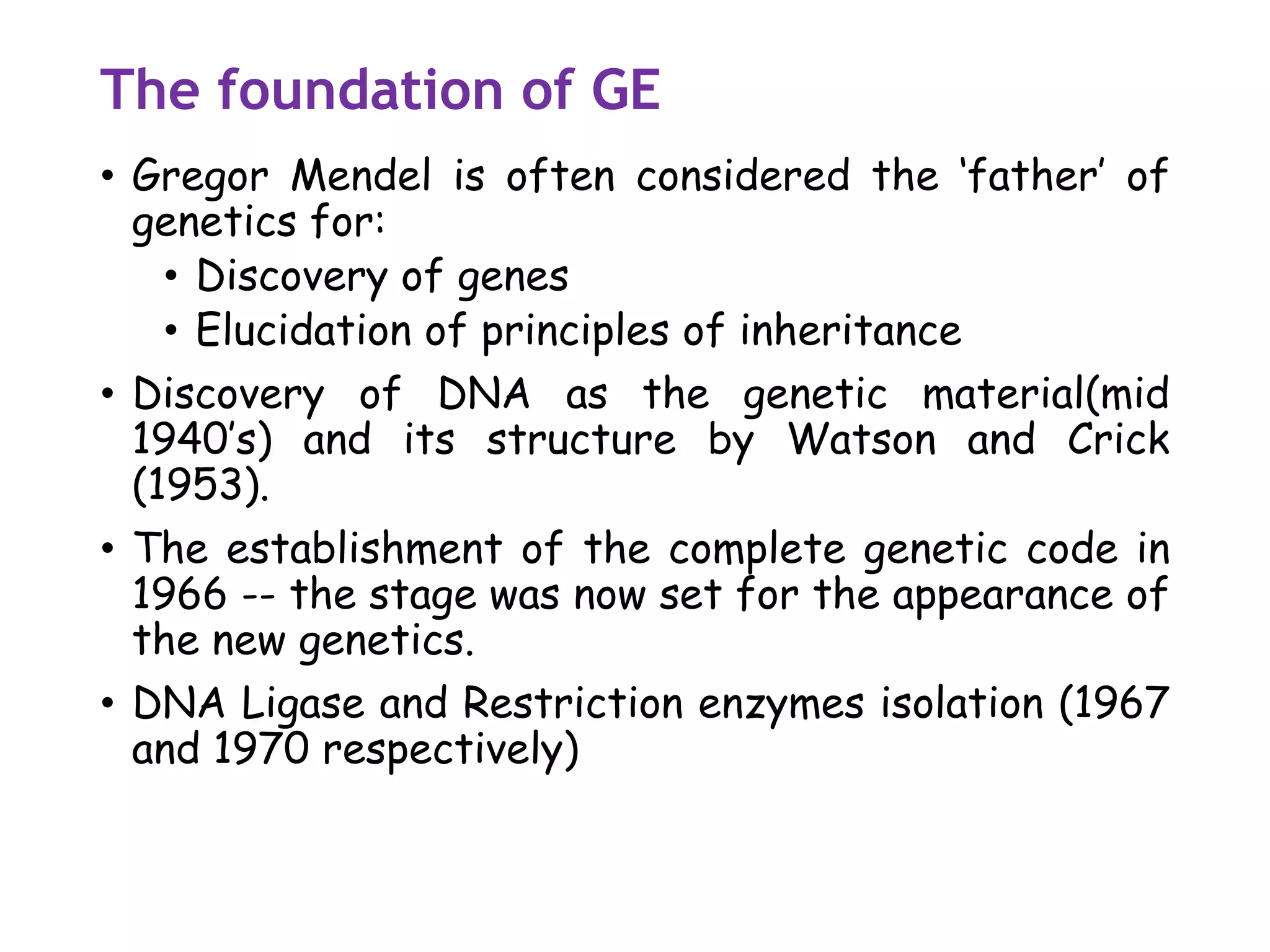

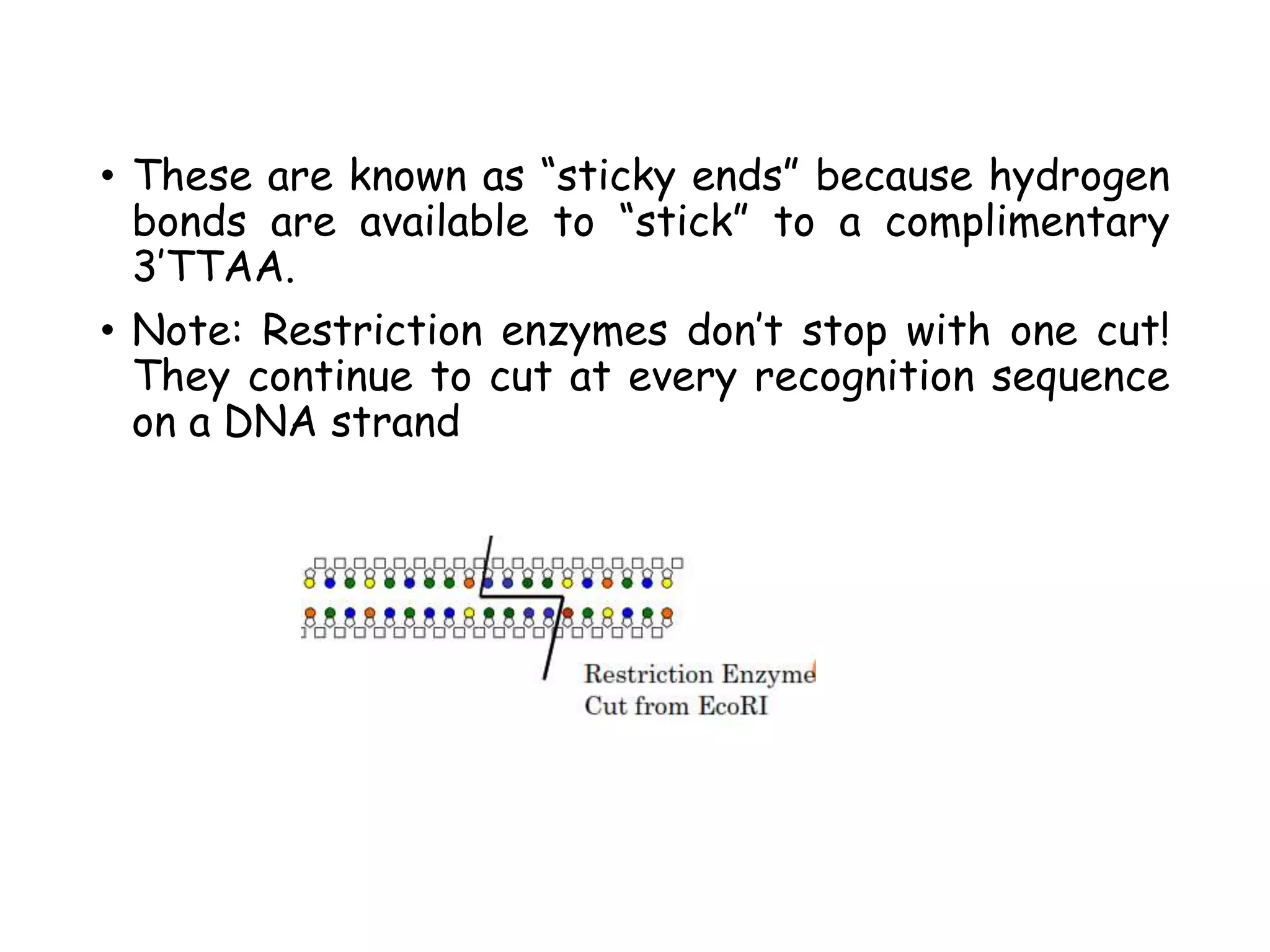

o Some restriction enzymes cut DNA at opposite

o They leave blunt ended DNA fragments

base

o These are called blunt end cutters

c-T

I i

I 1

c-T

I I

A-G A-G

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

q1

l

I

f

f

I

I

I

1

t

Alul If

fI I It t

T-C G-A T- € G-A

c~c c~c

I I

c-c,

I

I

G - c l

q

I 1I

1Haelll I 1

- l h h h] { '- ±f ( - '

[el h h h](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-200312055538/75/1-introduction-to-genetic-engineering-and-restriction-enzymes-36-2048.jpg)

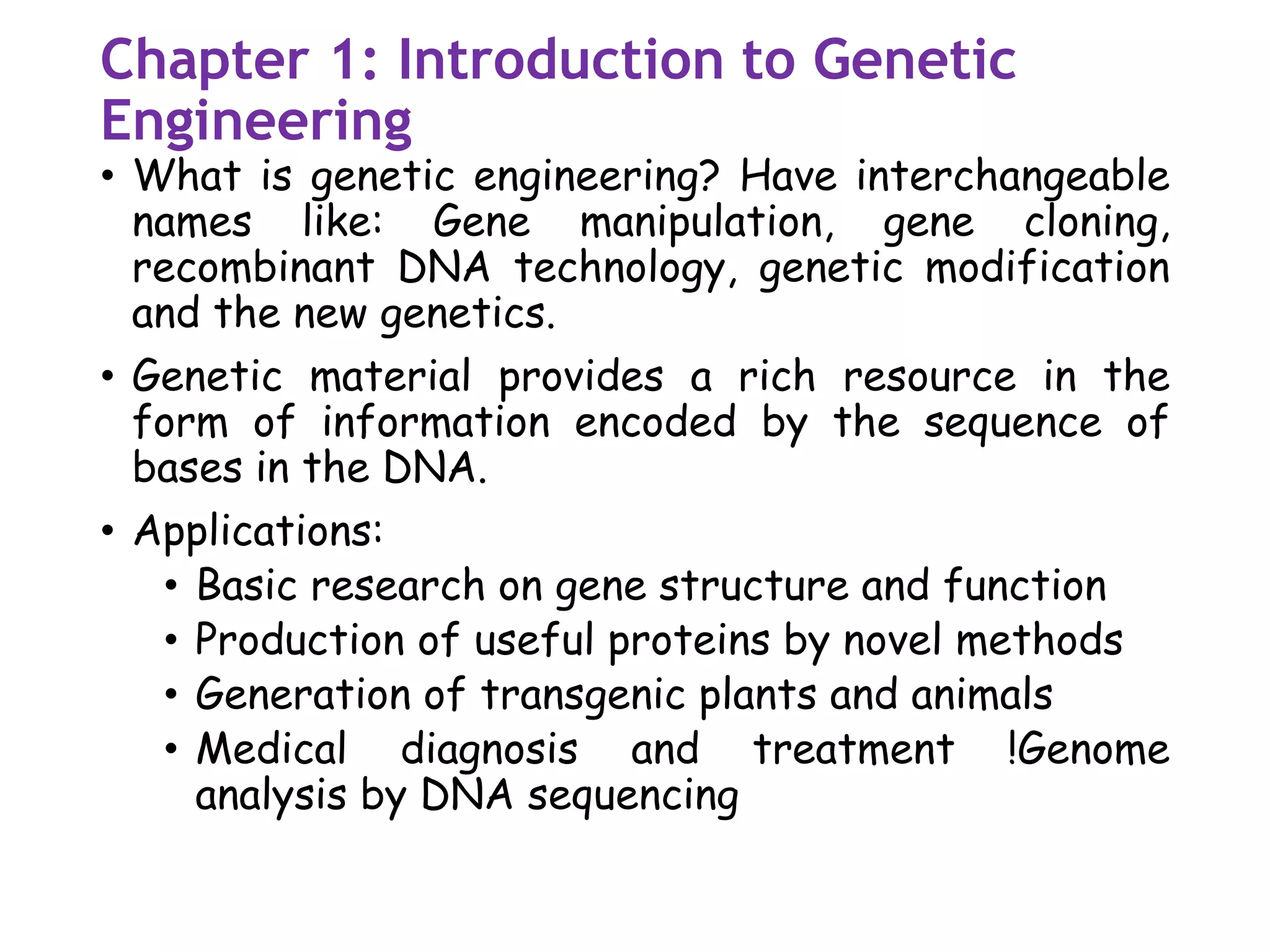

![3)Taq DNA ligase [NAD+ as cofactor]

• The gene encoding thermostable ligases have been

identified from several thermophilic bacteria.

• Several of this ligase have been cloned and

expressed to high levels in E.coli

• It is used in the detection of mutation as

thermostable DNA ligase and retain their activities

after exposure to higher temp for multiple rounds

• it detects mutation in mammalian DNA during

amplification reactions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-200312055538/75/1-introduction-to-genetic-engineering-and-restriction-enzymes-41-2048.jpg)