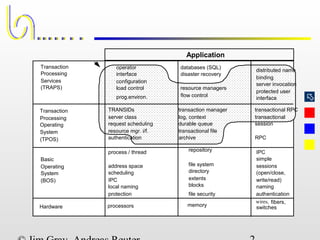

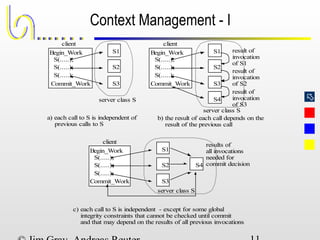

The document discusses transaction processing concepts including:

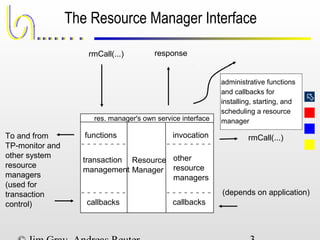

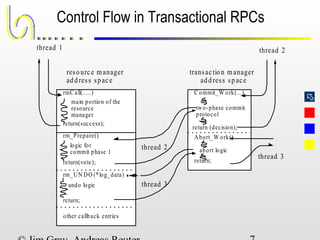

1) Transaction processing monitors (TP monitors) manage transactions and interface with resource managers like databases.

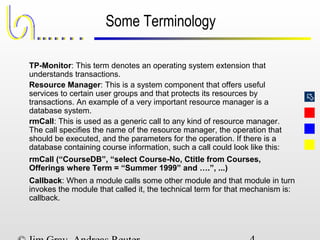

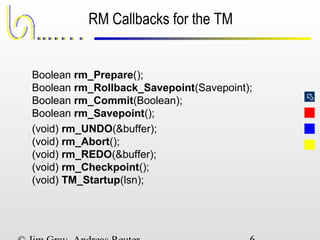

2) Resource managers provide services to users and protect resources using transactions. They interface with the TP monitor.

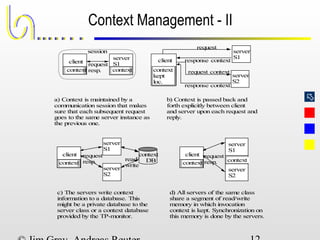

3) Context information like a user's position in a result set needs to be managed across multiple requests to ensure consistency.

![

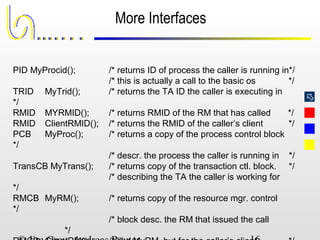

Some Interface Definitions

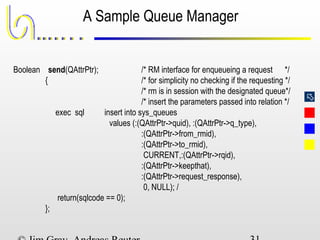

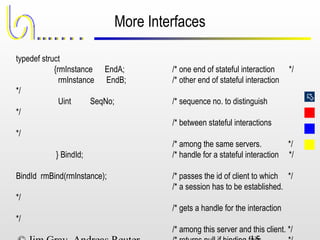

typedef struct /* handle for identifying the specific instantiation */

{ /* of a resource manager */

NODEID nodeid; /* node where process lives */

PID pid; /* process request is bound to */

TIMESTAMP birthdate; /* time of server creation */

} rmInstance; /* identifies a specific server */

typedef struct /* resource manager parameters */

{ Ulong CB_length; /* number of bytes in CB */

char CB_bytes [CB_length]; /* byte string */

} rmParams;

Boolean rmCall(RMNAME, /*inv. of RM named RMNAME */

Bindld* BoundTo, /* expl. with bind mechanism */

rmParams * InParams, /* params to the server */

rmParams * OutResults); /* results from server */](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/05tpmonorbs-150218104234-conversion-gate01/85/05-tp-mon_orbs-5-320.jpg)

![

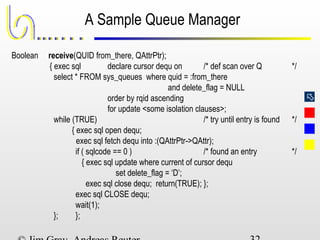

Name Binding for rmCalls

RMNAME address

name server

interface ptype

mailer farnode.mailserver

order entry

order entry

order entry

snode1.prod

snode2.prod

snode3.prod

sqldb database.server

***

***

***

***

***

RMTable

ResMgrName

rmid

RMactive

RMup

...

RMPR_chain

rm_entry[]

...

rm_Savepoint

rm_Prepare

rm_Commit

...

***

***

DebitCredit

DebitCredit

NearNode.1

NearNode.2

cached

part

of name

server

***DebitCredit NearNode.1

***DebitCredit NearNode.2

sqldb database.server ***

ProcessIx

busy

NextProcess

<RMNAME, EntryName>Step 1:

RM locally

available ?

Step 2

(yes):

Bind to

that

RMID

Step 2 (no):

Find a node

in the name

server;

send request

via RPC; do

local

binding at

that node

Step 3:

Find an idle

process

Step 4:

Find entry

point address

RPC to other node;

there it will be local

binding

Step 5: activate process at entry point address](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/05tpmonorbs-150218104234-conversion-gate01/85/05-tp-mon_orbs-18-320.jpg)