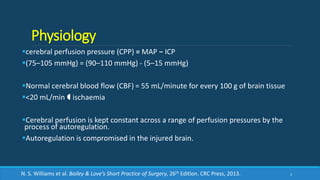

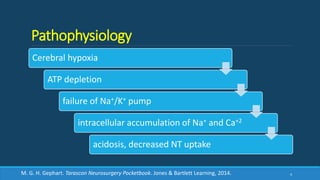

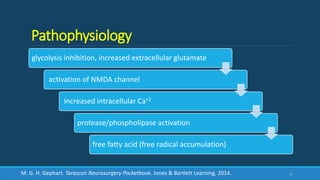

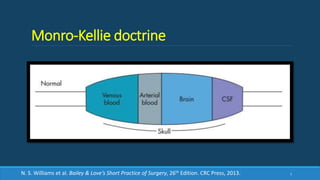

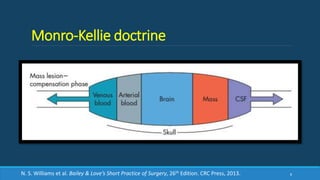

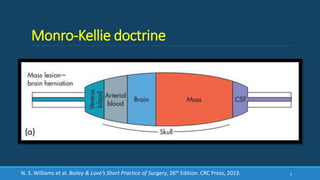

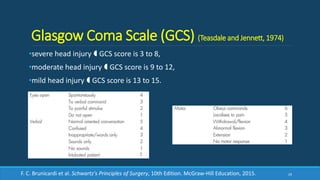

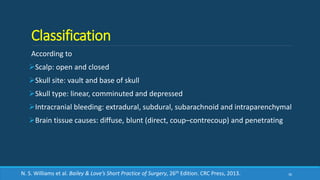

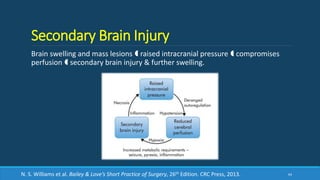

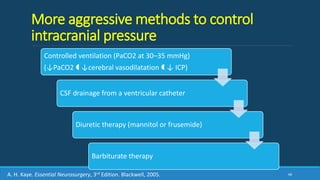

This document provides a comprehensive overview of head injury, detailing physiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology, initial evaluation, management, and outcomes. It emphasizes the importance of cerebral perfusion, classification of injuries, and the evaluation and management protocols, including CT scan criteria and indications for surgery. The content highlights critical considerations for assessing head injuries to ensure effective diagnosis and treatment.