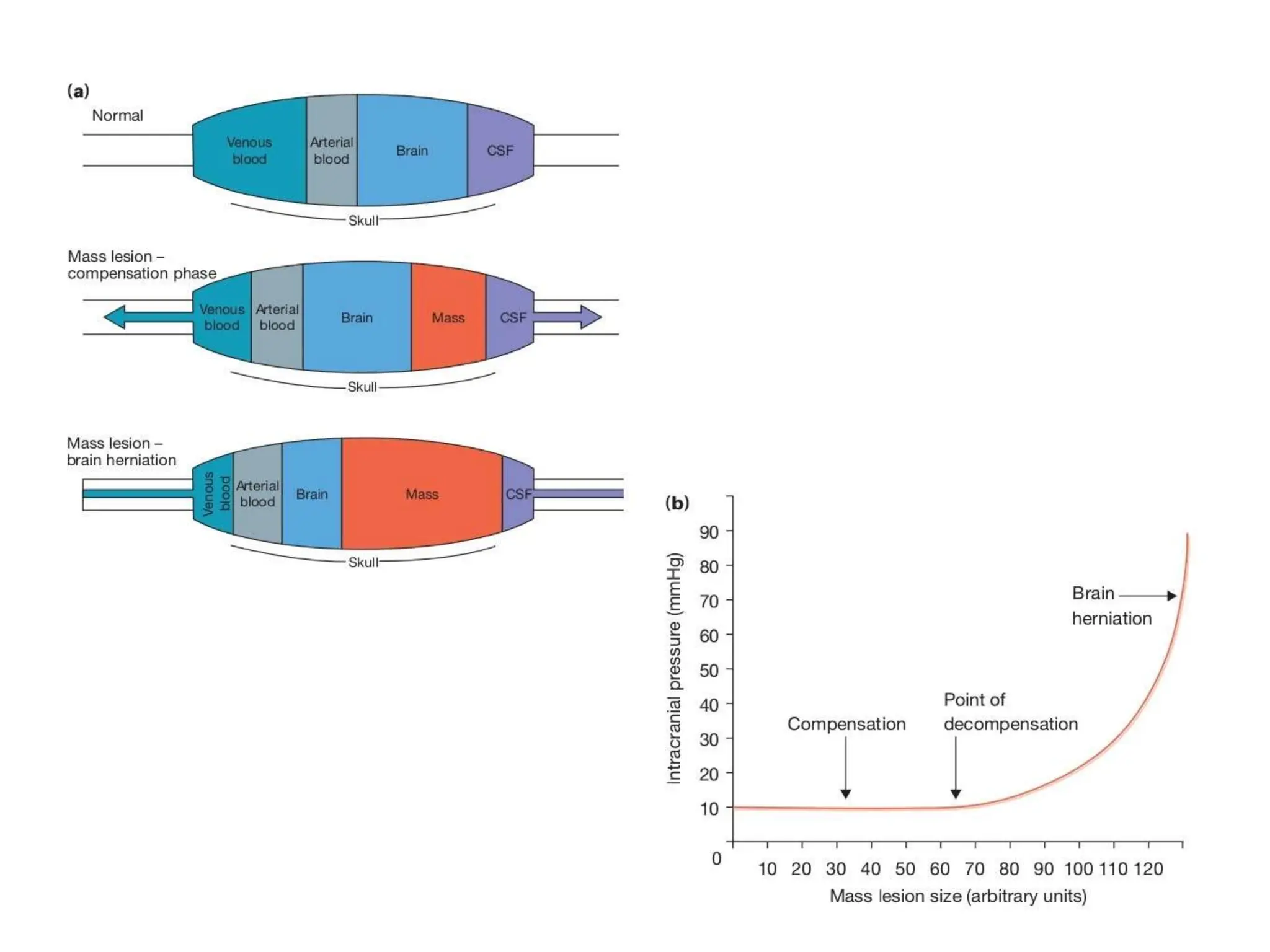

- Traumatic brain injury results from a primary impact injury and secondary injury in subsequent hours and days. Understanding intracranial pressure is key to minimizing secondary injury.

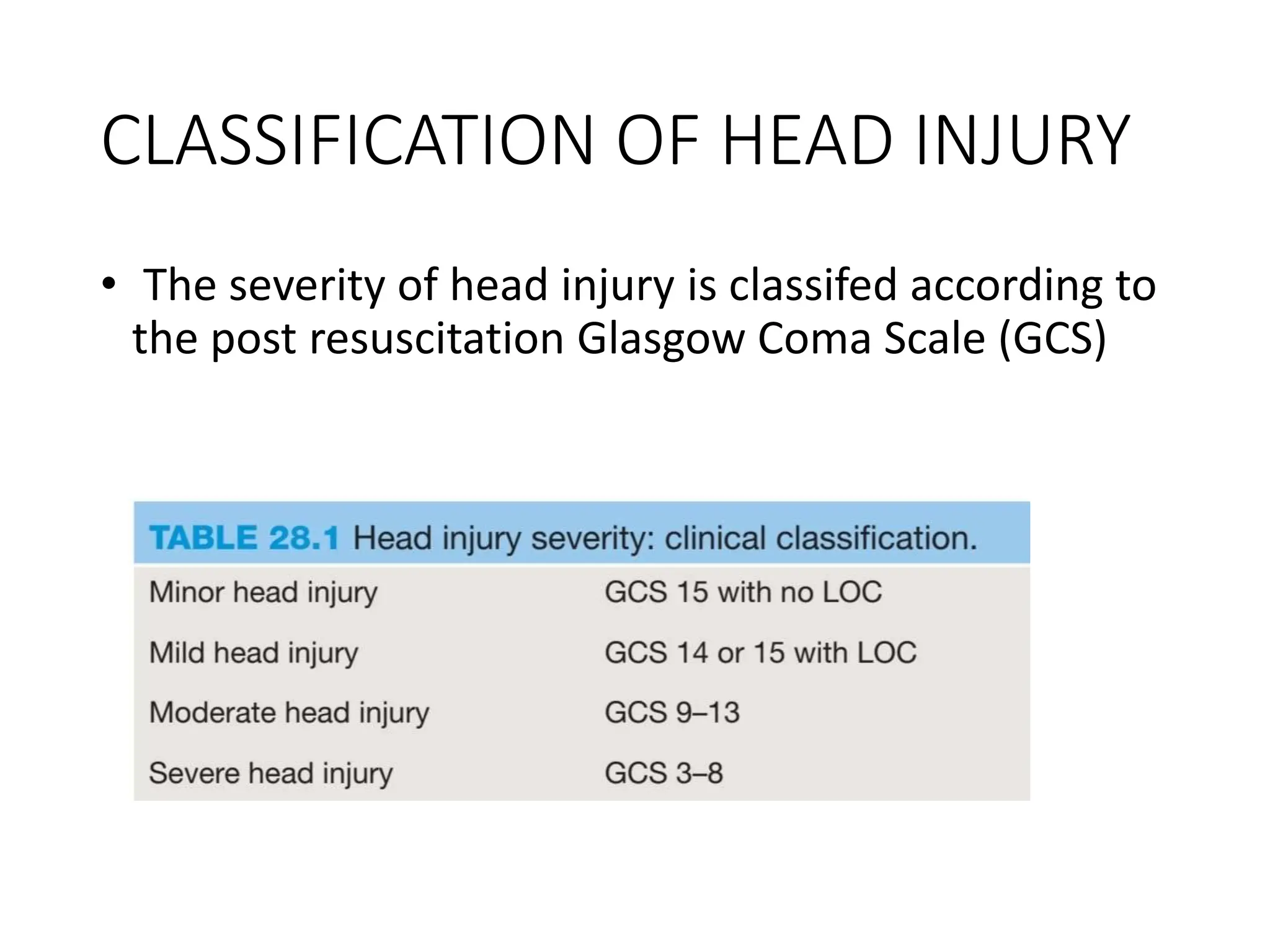

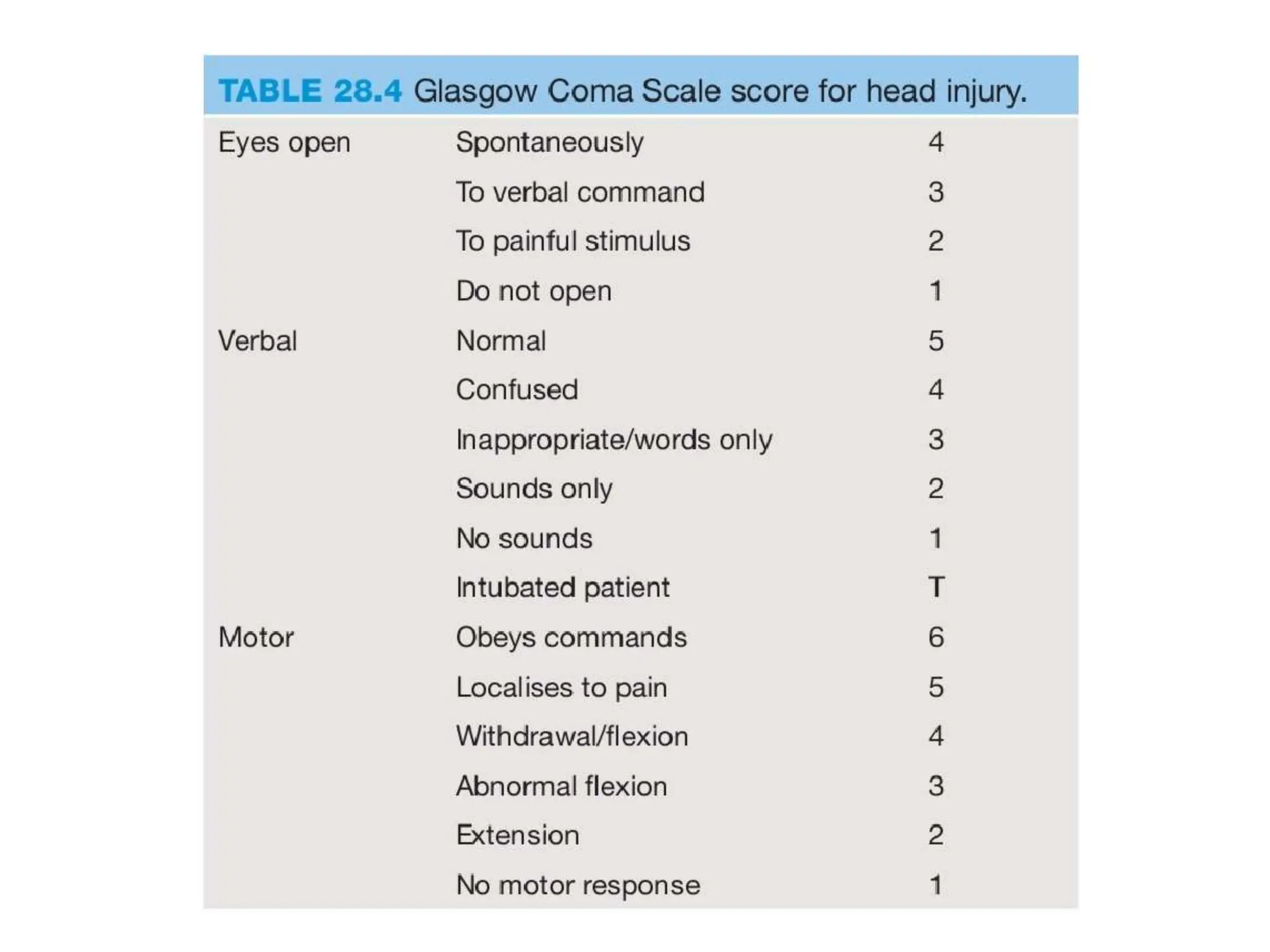

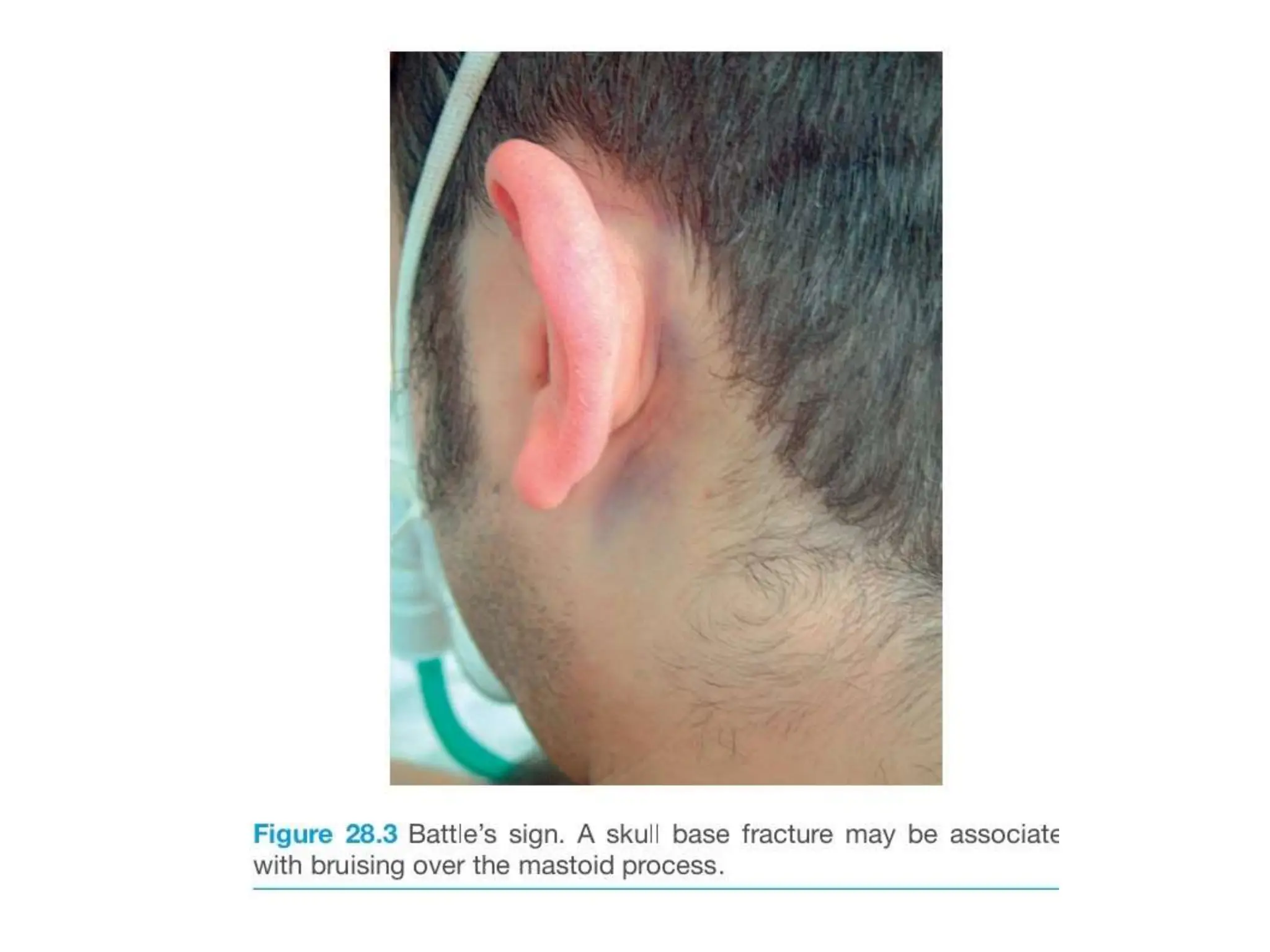

- Moderate and severe TBI require resuscitation per ATLS guidelines. A thorough history including mechanism of injury and neurological progression is important. Examination should check pupils, GCS, and spine.

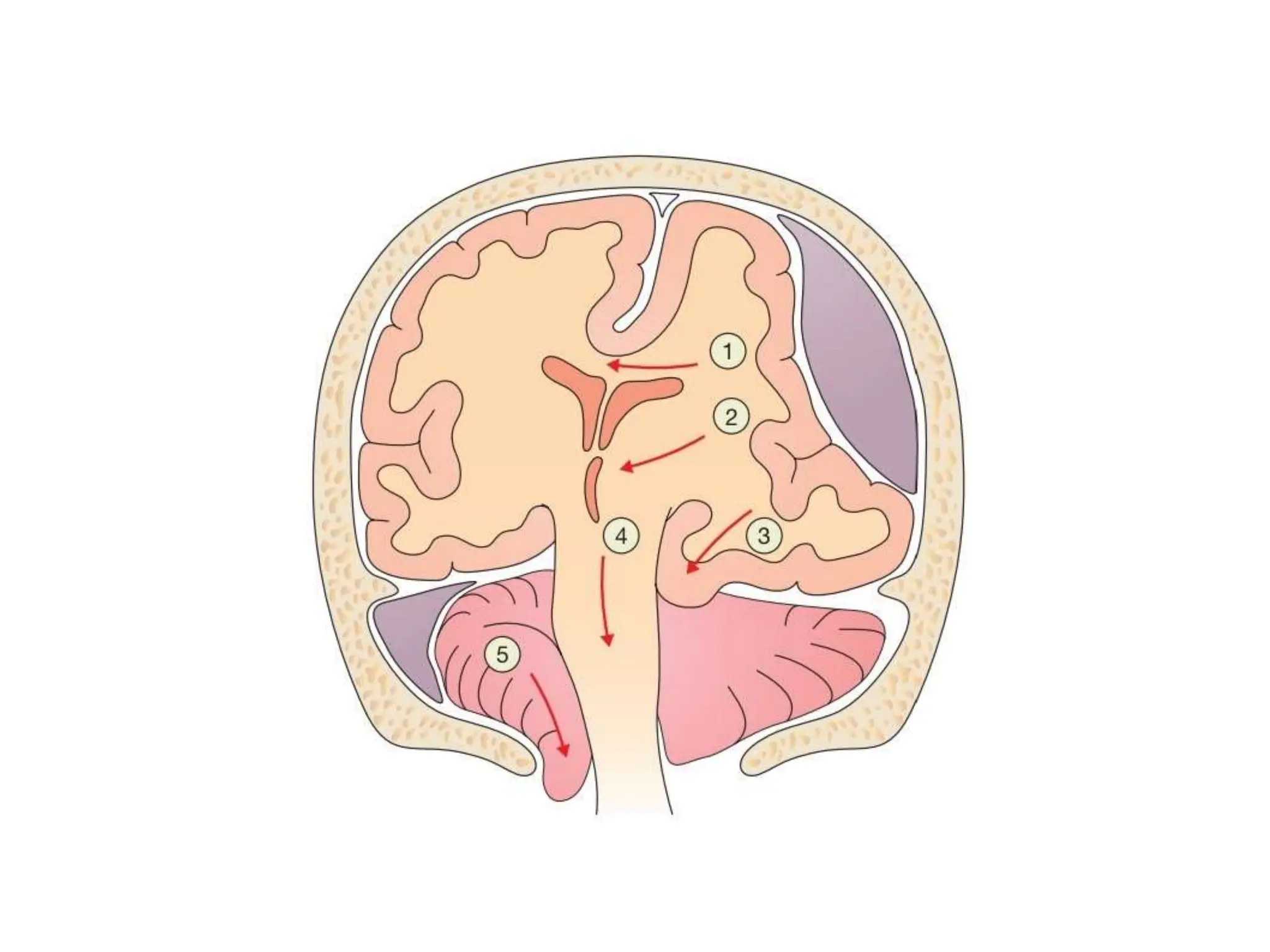

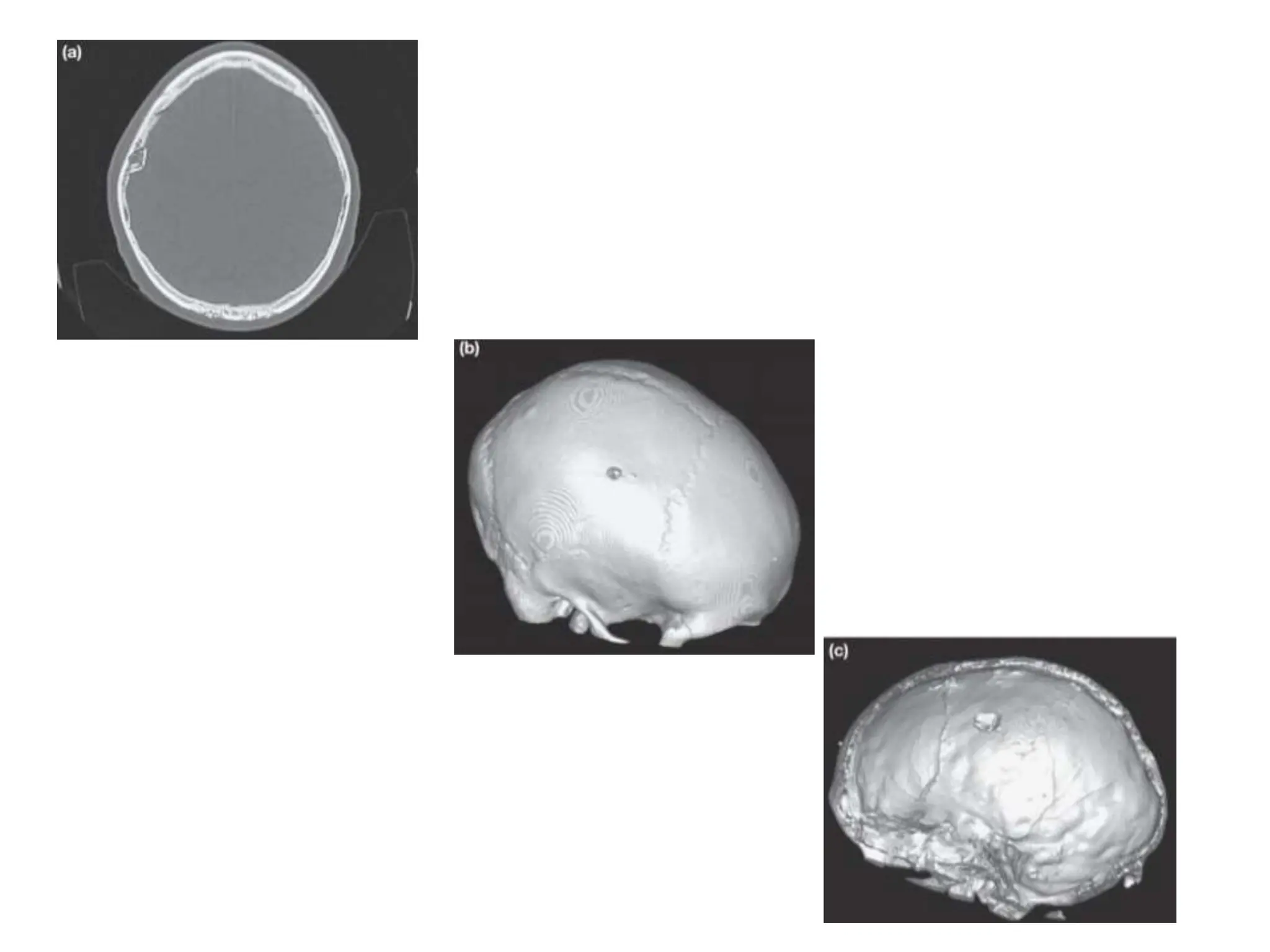

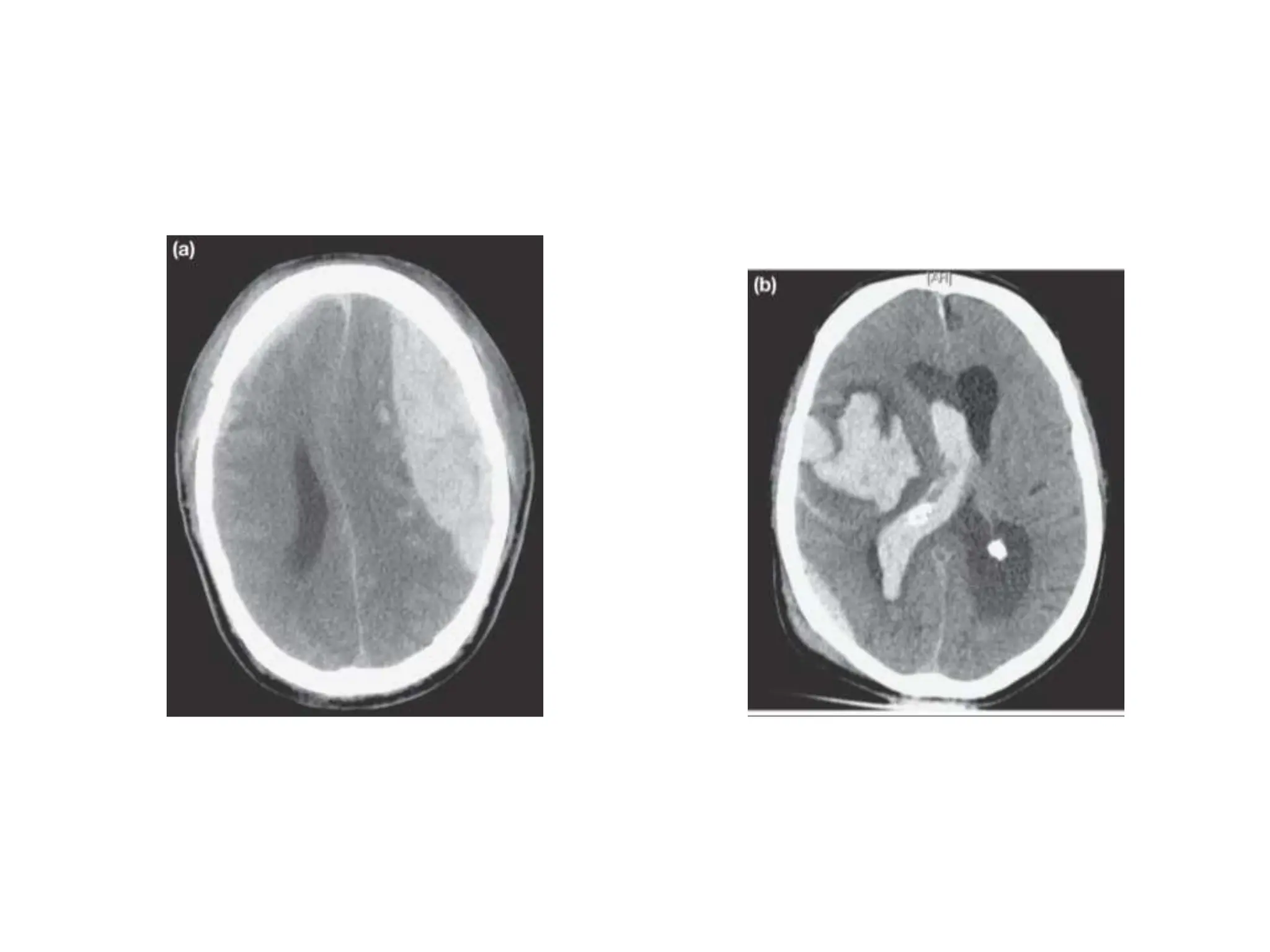

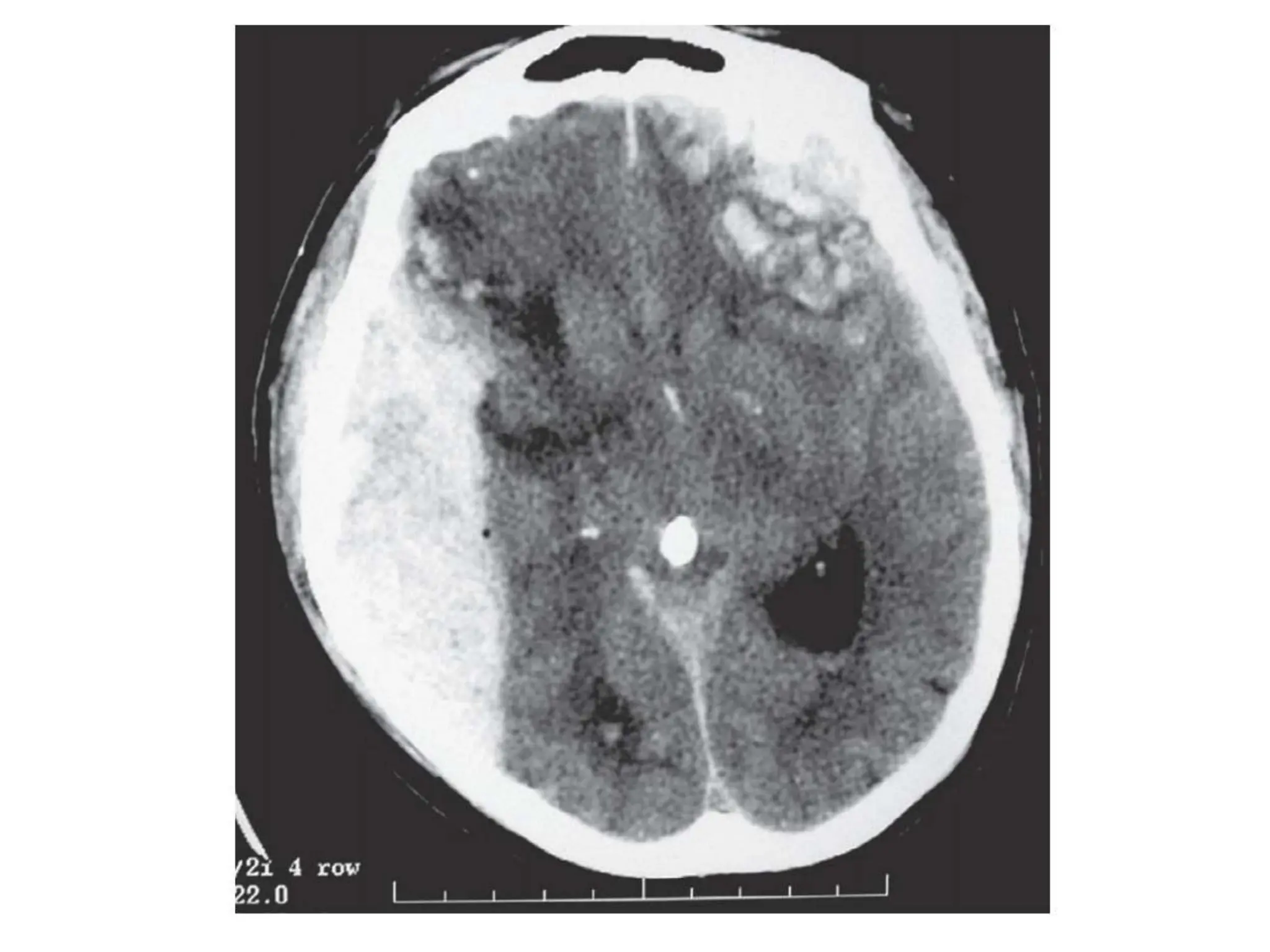

- Common surgical pathologies include extradural hematoma, subdural hematoma, contusions, and diffuse axonal injury which can be seen on CT and require different management.