This dissertation describes the development and pilot testing of tools to evaluate the international-mindedness and global engagement (IMaGE) of schools. The author conducted a literature review to define IMaGE and identify 8 factors ("radials") that influence it. Rubrics were created to measure each radial. The tools were pilot tested via case study at the author's international school in Japan. 10 faculty volunteers used the rubrics to assess the school's IMaGE, generating a "web chart." Results provided preliminary feedback on the school's IMaGE and identified areas for improvement. While limitations restrict reliability, the web chart showed potential as an evaluation tool if further developed and tested with larger samples. The study aimed to advance understanding of

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

9!

educationalists are currently drowning in a sea of seemingly similar terms” (Marshall 2007). There is

great variability between schools offering apparently similar experiences (Haywood 2007; Hayden

2011; Yamato 2003), and schools can become accredited, authorized or evaluated by a range of

agencies (Fertig 2007, 2015; Murphy 2012).

With clear descriptors for comparative purposes (Taylor 2013), any school might apply the

IMaGE tools, and each school would show a different pattern of degrees of quality: for example, a

multicultural international school, a local school offering an ‘internationalised’ curriculum, an

‘overseas school’ of one nation or a national school with a high immigrant population would each

have a unique IMaGE. In other words, “an international school may offer an education that makes no

claims to be international, while an international education may be experienced by a student that has

attended a school that has not identified itself as international” (Hayden & Thompson 1995),

Necessarily limited to the international dimensions of a school, the tool seeks only to

visualize the degrees of quality (characteristics) of the various radials (factors) that contribute to the

school’s IMaGE; quality here being used in a descriptive yet non-judgemental sense (Nikel & Lowe

2010), rather than Alderman and Brown’s (2005) “public and independent affirmation” as part of a

high-stakes external audit. Where it is possible that adherence to too restrictive a set of standards

might lead to isomorphism (schools becoming similar through competition), it is not a normative scale

in which some schools are ‘better than’ others (Shields 2015), but which illustrates a school’s unique

IMaGE in relation to others. I proposed that potential uses for the tools might include tracking a

school’s development of IMaGE over time, as a component of self-study for external bodies, as a

comparative tool for schools in a similar area or simply as an internal audit for a school exploring

issues of international education (Taylor 2013); “a culturally unbiased instrument or process for

measuring IM is [also] needed in the field.” (Duckworth, Levy & Levy 2005).

Since completing the EIC paper in 2012, I have come across further sources and

developments that have helped mature the web-chart visualization, including the updated and

comprehensive SAGE Handbook of Research in International Education (Hayden, Levy & Thompson

2015), Miri Yemini’s 2012 explorations of internationalization assessment in schools, Singh & Qi’s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-9-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

12!

Chapter 2: Literature Review

With such a rapidly-developing field of research, this could be a constantly fluid project,

adapting and evolving as the landscape of international education shifts. In this chapter, I review

literature on definitions of IMaGE, contemporary attempts and protocols used to measure or evaluate

IMaGE and key literature regarding factors that influence the development of IMaGE in a school. The

combined findings of the literature review will form the basis for the development of the prototype

IMaGE rubrics (Appendix 2).

2.1 Defining International Mindedness & Global Engagement

Although the International Schools Association’s (ISA 2011) self-study guide for

internationalism in education “offers no preconceived definitions or interpretation of internationalism

or international-mindedness”, instead opting to allow the school to “speak to and for itself”, Swain

(2007, in Singh & Qi 2013) argues that “defining and applying international-mindedness [...] might

be used as a basis for formal learning”. In my experience it is helpful to provide a common definition

for IMaGE that can be used by all stakeholders; given the potential future application for comparison

between schools (or within a changing school over time), it may be necessary to have a stable

reference for interpretation of the rubrics and questionnaires. In my EIC and RME assignments, I

stated that

“a school that promotes a high degree of IMaGE in its students demonstrates a commitment

to international understanding and education for a sustainable future. Through its

curriculum, faculty and learning opportunities it provides opportunities for its students to

appreciate and engage with a wide range of perspectives, cultures and values. Its learners

demonstrate compassion for others through their thoughts and actions, and are engaged in

meaningful service and action with the wider world.” (Taylor 2013, 2015).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-12-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

14!

cultural pluralism, efficacy, global centrism, and interconnectedness), were informative in developing

the radials and elements of the web chart.

The IBO stress that learners need to understand “their place in their local community as well

as in an increasingly interdependent, globalized world” in a process that “starts with self-awareness

and encompasses the individual and the local/national and cultural setting of the school as well as

exploring the wider environment.” (IBO 2009), and defining an internationally-minded individual as

one who “values the world as the broadest context for learning, develops conceptual understanding

across a range of subjects and offers opportunities to inquire, act and reflect” (IBO 2012a). Common

elements of IM definitions are found in much work, including a sense of ‘self’ and orientation in the

world, inter-connectedness, intercultural understanding and responsibility for the future and others

(Muller 2012; Skelton 2007; Skelton 2013; Hersey 2012; Duckworth, Levy & Levy 2005).

Building on the mindset of IM, and the sense of responsibility and action that comes through

some of the definitions so far, is global engagement (GE), defined by the IBO as a “commitment to

address humanity’s greatest challenges in the classroom and beyond, [...] developing opportunities to

engage with a wide range of locally, nationally and globally significant issues and ideas” (IBO

2012b). Engagement should be interpreted as the actions of an internationally-minded individual, and

may give more of the ‘observable outcomes’ of education for IM mentioned by Haywood (2015, p80).

A distinction should be made here between global engagement and global citizenship; terms that

sound similar but are again a source of potential confusion (Marshall 2007). Global citizenship should

be interpreted as the means through which a globally engaged individual takes action, “understood as

a multidimensional construct that hinges on the interrelated dimensions of social responsibility, global

competence, and global civic engagement” (Fig. 2, Morais & Ogden 2011). Global citizenship,

therefore, reflects a set of skills and a fluid body of knowledge that could be built into a school’s

curriculum (OXFAM 2016), a complex set of practices that has been included as its own radial in the

web chart. Global competence bears highlighting in the final definition, making clear that to be

successfully globally engaged, one must be armed with an appropriate set of skills and informed

global knowledge (Morais & Ogden 2011).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-14-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

15!

Figure 2: Morais & Ogden’s (2011) Global Citizenship Model

Interestingly former Director General of the IBO, George Walker, described international-

mindedness as a ‘20th century’ notion of ‘otherness’ or of events occurring in ‘distant, exotic’ places;

he preferred global-mindedness, with its suggestion of inter-connectedness, and with four components

that reflect “21st Century realities[...]: emotional intelligence, communication, (inter)cultural

understanding and collaboration” (Hill, 2000 & Walker, 2004 in Hersey 2012). Although this may

be in keeping (perhaps unintentionally) with language around the globalization of international

education (Cambridge 2002; Bates 2010; Bunnell 2008), I elected to use the compound term

international-mindedness and global engagement (IMaGE). Other than the obvious neatness of the

acronym and its suggestion of visualisation, its components can be easily recognized and interpreted,

even if the reader is not familiar with the literature.

Recognizing that technology and accessible international travel have removed many barriers

to global communication, learning and action (Hill, 2000 & Walker, 2004 in (Hersey 2012), studies of

IMaGE education offer new insights. We can see the shift from ‘international understanding’ as a

construct of ‘us vs. them’, to more inclusive international-mindedness as an inter-personal (or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-15-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

21!

2.3 Evolving the web-chart

Since 2012, some development has taken place in

the selection and description of the elements of the rubrics

and the structure of the web chart. Initial anecdotal

response to the web chart was positive, as an easily-

interpreted, multi-faceted graphic (Tague 2005). The

concentric design, with outward progression representing

an increasing quality echoes Hill’s (2006) cultural model of

interaction, as well as the Global Competence Aptitude

ModelTM

(Hunter, Singh & Habick, n.d., Fig 3), where the

inner (green) circles represent internal readiness, the blue

represent external readiness and which itself provides a

useful toolkit for development of skills and attributes in the

Global Citizenship Education radial.

Figure 3: Global Competence Aptitude ModelTM

,

from http://www.globallycompetent.com/model

In keeping with Nikel and Lowe’s (2010) model of the fabric of quality in education, I have

maintained the positioning of the radials to try to communicate the tensions between radials – some

have overlapping or complementary elements. For example, intercultural relationships are seen as

important in the Students & Transition, Faculty & Pedagogy and Community & Culture radials.

Building on the assertion that “a contextually relevant balance [...] does not imply equalization”

(Nikel & Lowe 2010), I have attempted to maintain balance through the distribution of ideas in the

radials and underlying elements. The Values & Ideology radial, with a high degree of commonality

across other measures of internationalism (IB 2014; CIS 2016; ISA 2011), has five contributing

elements, giving each a relatively high weighting in the development of the school’s IMaGE.

Contrastingly, in the Students & Transition radial, with seven elements and more varied approaches to

their teaching and measurement, each element therefore contributes slightly less to the overall IMaGE

of the school. Table 1 below presents a comparison of the ‘big ideas’ of the foundational resources I

have used, in an attempt to identify common themes and categories to inform the adjustment of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-21-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

24!

These adjustment, in alignment with Singh & Qi’s (2013) five concepts of 21st

century

international-mindedness, will be used to populate and describe the elements of the radials for the

IMaGE tool evaluation rubrics, and these will be discussed in the next section.

2.4 Influences on IMaGE: Web-chart radials and elements

Although the main focus of this paper is to pilot-test the prototype IMaGE tools (web chart

and rubrics), it is necessary to justify some of the choices made in the selection of radial elements and

their descriptors, with the complete list of elements presented in table 2. Some key sources used in the

development of the elements descriptors are presented under a few element columns of the prototype

rubrics in Appendix 2, as an example of how the completed rubrics might present their pedigree. The

standards outlined in the tools compared above offer much of the structure of the IMaGE tools, yet

there has been significant supplementation from literature sources. Although it is not possible in the

scope of this assignment to justify the choices of all four degrees of quality of all 49 identified

elements, I will justify some important or counter-intuitive choices and concepts that cross radials,

adding to the “tension in the fabric of quality” (Nikel & Lowe 2010).

Structures from the ISA, CIS and IB are common in their description of elements of mission

and core values, for example. Where Sylvester (1998) noted that “the greatest challenge […] facing

multilateral international schools is one of worldview”, we have since seen the development – almost

homogenization (Fertig 2007) – of international school missions. In keeping with Cambridge (2003)

and Muller (2013), who discuss the internationalist and globalist missions of schools and the role of

internationalization language in the foundational documents of schools, the ‘Mission & Vision’ and

Core Values & Rules’ elements are identified. Internationalization is most likely a deliberate choice

(Cambridge 2002), with adoption of international standards balancing the idealistic internationalist

worldview mission of the school with the pragmatic realities of school business (Cambridge &

Thompson 2014); the adoption of international programmes not only providing market legitimacy and

brand recognition for the school (Murphy 2012), but also affording tools, resources and definitions for

their development in line with values and ideology.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-24-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

25!

Multilingualism sits alongside intercultural understanding and global engagement in the IB’s

conceptual framework for international-mindedness (IB 2013), yet its realisation reaches beyond the

simple acquisition of a second (or third) language (Nieto 2009; Singh & Qi 2013). Multilinguals

“experience the world differently […] because culturally important concepts and ways of thinking

[…] are embedded in language” (Duckworth, Levy & Levy 2005). Singh & Qi (2013) assert that an

effectively multilingual learner can make connections between languages, using them as a

“multimodal communication for international understanding”, leading to their classification of the

school’s contribution as post-monolingual language learning. Multilingualism, therefore influences

multiple radials and is clearly a shared responsibility of an international school, contributing to the

elements of ‘Promotions & Publications’ and ‘Access Languages’ the Values & Ideology radial,

‘Multilingual Support’ in Faculty & Pedagogy radial, ‘Curriculum Offerings’, ‘Multilingualism in the

Curriculum’ and ‘Communicating the Curriculum’ in the Core Curriculum radial and ‘Intercultural

Engagement’ in the Ethical Action radial.

Another wide-reaching concept is the perception of internationalism by groups and

individuals, including ‘Leadership Communication’ and ‘Recruitment’ in the Leadership, Policy and

Governance radial, ‘Students & Internationalism’ in the Students & Transition radial, ‘Faculty &

Internationalism’ and ‘Professional Development’ in the Faculty & Pedagogy radial, ‘Community,

Culture & Events’ in the Community & Culture radial, ‘Curriculum Frameworks’ and ‘Curriculum

Content and Materials’ in the Core Curriculum radial, and ‘Values Education’ in the Global

Citizenship Education radial. Where many attempts at measuring perceptions of IM have been made,

the development of true IM as an extension of self may be riddled with challenges (Skelton 2015),

perhaps harder still to accurately measure the impacts of the school on the student’s IMaGE (after

Hayden, Rancic & Thompson 2000). However, tools such as the Global Mindedness Scale, the Global

Citizenship Scale or the Global Competence Model might be put to use to measure perspectives of

students, teachers (including applicants), leadership and governance, as well as to inform strategic and

instructional planning.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-25-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

56!

Table 15: Evaluating the clarity of the web chart visualization (summary data, n=10)

To what extent do you agree with each of these statements? Mean STDEV Mode

2a The web chart is easy to understand without explanation. 3.8 0.79 4(7)

2b The web chart is easy to understand with background information. 4.4 0.52 4(6)

2c The web chart would be understandable to a non-educator. 3.2 1.03 2,3,4 (3 each)

Table 16: Evaluating the presentation and clarity of the rubrics (summary data, n=10)

To what extent do you agree with each of these statements? Mean STDEV Mode

4a The rubric descriptors are understandable to me. 4.4 0.7 5 (5)

4b The rubric descriptors are accurate, to the best of my knowledge. 4.2 0.79 4, 5 (4)

4c The rubric descriptors are comprehensive, to the best of my knowledge. 4.2 0.92 4 (5)

4d The rubric descriptors provided would be understandable to a non-teaching audience. 2.5 0.97 •! (7)

With high mean and consistent modal ratings for the ‘teacher-facing’ questions, accompanied

by low variability, there was general consensus from the volunteers that the IMaGE tools were useful

and clear, giving a positive response in terms of the operability and validity of the tools, with

generally positive comments regarding the web as a visualization, though one volunteer suggested a

bar chart might be clearer for the viewer, and another requested a more colourful presentation to

differentiate between pre-test and best-fit data. Volunteers could see a potential value in the IMaGE

tools for use by the school as a whole, or with a wider organization, with one commenting that the

web chart might be used “like a logo/mark next to a school […] on a website or brochure,” with

another observing that is a “strong visual when matched with the rubric to describe the fine points/

concepts.”

Comments were more cautious when it came to the rubrics the process, however. Where one

volunteer commented that “I have never seen any rubric for internationalism, so it’s about time that

the public is exposed to this kind of rubric,” a recurring theme was of some confusion in the wording

(or formatting errors), and a more significant concern about who would complete the rubrics if they

were to be used for comparative purposes. Furthermore, two volunteers expressed concern about the

inclusion of seemingly unrelated elements being included in some radials (for example transition or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-56-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

67!

References

Alderman, G. & Brown, R., 2005. Can Quality Assurance Survive the Market? Accreditation and

Audit at the Crossroads. Higher Education Quarterly, 59(4), pp.313–328. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2005.00300.x. [Accessed 6 July 2016]

Allen, D. & Tanner, K., 2006. Rubrics: tools for making learning goals and evaluation criteria explicit

for both teachers and learners. CBE life sciences education, 5(3), pp.197–203.

Bates, R., 2010. Schooling Internationally: Globalisation, Internationalisation and the Future for

International Schools. London: Routledge.

Beerkens, E. et al., 2010. Indicator projects on internationalisation: Approaches, methods and

findings [online]. A report in the context of the European project ‘Indicators for Mapping and

Profiling Internationalization’ (IMPI). European Commission. Available at: !

http://cdigital.uv.mx/handle/123456789/31235. [Accessed July 5, 2016].

Bennet, M.J., 2014. Intercultural Development Research Institute - DMIS. The Developmental Model

of Intercultural Sensitivity. Available at: http://idrinstitute.org/page.asp?menu1=15[Accessed

July 8, 2016].

BERA, 2011. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Resarch, [online]. British Educational Research

Association. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-

guidelines-for-educational-research-2011. [Accessed Jan 22, 2016].

Berger-Kaye, C., 2004. The complete guide to service learning: Proven, practical ways to engage

students in civic responsibility, academic curriculum, & social action, Golden Valley,

Minnesota, USA: Free Spirit Publishing. Available at:

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=6eiL_zTB-

AYC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=berger-

kaye&ots=YHash1A3LZ&sig=pirXjfP7vk6k4wa7swRdfWz8Hnc. [Accessed May 15, 2016].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-67-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

68!

Berger-Kaye, C., 2007. Bring Learning to Life: What Is Service-Learning? A Guide for Parents.

USA: National Service-Learning Clearinghouse. Available at: http://www.servicelearning.org

[Accessed May 15, 2016].

Berger-Kaye, C, 2009. Service-Learning: The Time Is Now. Middle Ground, 13(2), p.10.

Available at: http://search.proquest.com/openview/33fdde8e88ccdb7205ad4089871a52eb/1?pq-

origsite=gscholar&cbl=27602. [Accessed May 15, 2016].

Bilewicz, M. & Bilewicz, A., 2012. Who defines humanity? Psychological and cultural obstacles to

omniculturalism. Culture & Psychology, 18(3), pp.331–344.

Boone, H.N. & Boone, D.A., 2012. Analyzing likert data. Journal of extension, 50(2), pp.1–5.

Bryman, A., 2007. Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Journal of mixed

methods research, 1(1), pp.8–22.

Bunnell, T., 2008. International education and the “second phase”: a framework for conceptualizing

its nature and for the future assessment of its effectiveness. Compare: A Journal of Comparative

and International Education, 38(4), pp.415–426.

Cambridge, J., 2002. Global Product Branding and International Education. Journal of Research in

International Education, 1(2), pp.227–243.

Cambridge, J., 2003. Identifying the Globalist and Internationalist Missions of International Schools.

International Schools Journal, 22(2), pp.54–58.

Cambridge, J. & Carthew, C., 2015. Schools Self-Evaluating Their International Values: A Case

Study. In Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th

Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of

Research in International Education. pp. 283-288. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Accessed from: https://www-dawsonera-com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/

[Accessed 6 July 2016]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-68-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

69!

Cambridge, J. & Thompson, J., 2001. Internationalism, international-mindedness, multiculturalism

and globalisation as concepts in defining international schools. Unpublished paper. Available

online at: http://staff.bath.ac.uk/edsjcc/intmindedness.html(accessed 22 September 2003).

Cambridge, J. & Thompson, J., 2004. Internationalism and globalization as contexts for international

education. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 34(2), pp.161–175.

Campbell, D.T. & Fiske, D.W., 1959. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-

multimethod matrix. Psychological bulletin, 56(2), pp.81–105.

Carifio, J. & Perla, R.J., 2007. Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and

urban legends about Likert scales and Likert response formats and their antidotes. Journal of

Social Sciences, 3(3), pp.106–116.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. Morrison, K. 2007., Research Methods in Education. 6th

Edition

[online]. London, UK: Routledge. Available from: http://www.myilibrary.com?ID=85853

[Accessed 10 July 2016].

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K., 2013. Research Methods in Education, 7th

Edition. London,

UK: Routledge.

Council of International Schools (CIS), 2016a. CIS International Accreditation Protocols 2016.

Available at: http://www.cois.org/page.cfm?p=2444[Accessed July 7, 2016].

Council of International Schools (CIS), 2016b. Global Citizenship. Council of International Schools

(CIS). Available at: http://www.cois.org/page.cfm?p=1801 [Accessed May 4, 2016].

Denscombe, M., 2008. Communities of practice a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach.

Journal of mixed methods research, 2(3), pp.270–283.

Denscombe, M., 2014. The Good Research Guide: For Small-scale Social Research Projects,

London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-69-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

70!

Duckworth, R.L., Levy, L.W. & Levy, J., 2005. Present and future teachers of the world’s children

How internationally-minded are they? Journal of Research in International Education, 4(3),

pp.279–311.

Durrant, G.B., 2009. Imputation methods for handling item!nonresponse in practice: methodological

issues and recent debates. International journal of social research methodology, 12(4), pp.293–

304.

Fail, H., 2007. The potential of the past in practice: Life histories of former international school

students. In Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of

Research in International Education. pp. 103-112. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Accessed from: https://www-dawsonera.com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/

[Accessed 6 July 2016]

Fail, H., Thompson, J. & Walker, G., 2004. Belonging, identity and Third Culture Kids Life histories

of former international school students. Journal of Research in International Education, 3(3),

pp.319–338. Available at: http://jri.sagepub.com/content/3/3/319.short.

Fertig, M., 2007. International school accreditation: Between a rock and a hard place? Journal of

Research in International Education, 6(3), pp.333–348.

Fertig, M., 2015. Quality Assurance in National and International Schools: Accreditation,

Authorization and Inspection. In Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (7th

Edition). The SAGE

Handbook of Research in International Education. pp. 447-457.

Fielding, N.G.F., Fielding, J.L.N.G. & Fielding, J.L., 1986. Linking data,

Fraenkel, J., Hyun, H. & Wallen, N., 2012. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education 8th

ed., McGraw-Hill Education.

Hayden, M. & Thompson, J., 1995. International Schools and International Education: a relationship

reviewed. Oxford Review of Education, 21(3), pp.327–345.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-70-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

71!

Hayden, M.C., Rancic, B.A. & Thompson, J.J., 2000. Being International: Student and teacher

perceptions from international schools. Oxford Review of Education, 26(1), pp.107–123.

Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/030549800103890.

Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (Eds), 2007. The SAGE Handbook of Research in International

Education. (6th Edition, online). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. Accessed from:

https://www-dawsonera-com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/ [Accessed 6 July

2016]

Hayden, M., 2011. Transnational spaces of education: the growth of the international school sector.

Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(2), pp.211–224.

Hayden, M., Mary, H. & Thompson, J., 2013. International Schools and International Education:

Improving Teaching, Management and Quality, Taylor & Francis. Available at:

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=v8MYnV4GEbsC.

Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (Eds), 2015. The SAGE Handbook of Research in International

Education. (7th Edition). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Haywood, T., 2007. A simple typology of international-mindedness and its implications for education.

In Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of Research

in International Education. pp. 79-89. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. Accessed from:

https://www-dawsonera-com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/ [Accessed 6 July

2016]

Hersey, M., 2012. The development of global-mindedness: School leadership perspectives. Florida

Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL. Available at:

http://fau.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fau%3A3862/datastream/OBJ/download/development_

of_global-mindedness.pdf.

Hett, E.J., 1991. The development of an instrument to measure global-mindedness, San Diego, USA:

University of San Diego Press.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-71-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

72!

Hill, I., 2000. Internationally-minded schools. The International Schools Journal, 20(1), p.24.

Hill, I., 2006. Student types, school types and their combined influence on the development of

intercultural understanding. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(1), pp.5–33.

Hill, I., 2015. The history and development of international-mindedness. In Hayden, M., Levy, J. &

Thompson, J. (7th Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of Research in International

Education. pp. 20-34. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. Accessed from:

https://goo.gl/UWTyld [Accessed 6 July 2016]

Hill, I., 2013. International-mindedness: Ian Hill explores the emergence of the term “internationally

minded.” International School Magazine, 15(2), pp.13–14.

Hunter, C., Singh, P. & Habick, T., Global Competence Aptitude Assessment® - Global Competence

ModelTM

. Global Competence Aptitude Assessment. Available at:

http://www.globallycompetent.com/model/[Accessed July 8, 2016].

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2009. The Diploma Programme: A basis for

practice, International Baccalaureate Organization.

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2012a. What is international mindedness? [Online].

IB Answers. Available at: https://ibanswers.ibo.org/app/answers/detail/a_id/3341/~/what-is-

international-mindedness%3F [Accessed May 1, 2016].

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2012b. What is global engagement? [Online]. IB

Answers. Available from: https://ibanswers.ibo.org/app/answers/detail/a_id/3338/related/1/

session/L2F2LzEvdGltZS8xNDYyMDgzOTU3L3NpZC9VUW51eW5QbQ== [Accessed May

1, 2016].

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2013. What is an IB Education? [Online]. Available

from: http://www.ibo.org/globalassets/digital-tookit/brochures/what-is-an-ib-education-en.pdf

[Accessed May 1, 2016].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-72-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

73!

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2014. Programme Standards and Practices [Online].

Available from: http://www.ibo.org/globalassets/publications/become-an-ib-school/programme-

standards-and-practices-en.pdf [Accessed May 1, 2016].

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), 2016. Postcards to the Director General [Online].

The IB Community Blog. Available from: http://blogs.ibo.org/blog/2016/03/16/postcards-to-the-

director-general/ [Accessed July 7, 2016].

International Schools Association (ISA), 2011. Internationalism in Schools - a Self-Study Guide,

[Online] Available at: http://isaschools.org/portfolio-view/internationalism-in-schools-a-self-

study-guide/.

Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J. & Turner, L.A., 2007. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods

Research. Journal of mixed methods research, 1(2), pp.112–133.

Jonsson, A. & Svingby, G., 2007. The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational

consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), pp.130–144.

Ladson-Billings, G., 1992. Culturally relevant teaching: The key to making multicultural education

work. Research and multicultural education: From the margins to the mainstream, pp.106–

121. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=N4KOAgAAQBAJ

&oi=fnd&pg=PA102&dq=ladson+billings+education&ots=suIp_jsbi&sig=SUDdB_6_3hlP5u

t4a9PlubLJsE8.

Ladson!Billings, G., 1995a. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy.

Theory into practice, 34(3), pp.159–165. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675.

Ladson-Billings, G., 1995b. Multicultural Teacher Education: Research, Practice, and Policy.

Available at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED382738 [Accessed May 1, 2016].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-73-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

74!

Lauder, H., 2007. International schools, education and globalization: towards a research agenda. In

Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of Research in

International Education. pp. 441-449. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. Accessed from:

https://www-dawsonera-com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/ [Accessed 6 July

2016]

Lowe, J., 1998. International and comparative education. The International Schools Journal, 17(2),

p.18.

Lindsay, J. & Davis, V., 2012. Flattening classrooms, engaging minds: Move to global collaboration

one step at a time. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Pearson Higher Ed.

MacBeath, J., 2005. Schools Must Speak for Themselves: The Case for School Self-Evaluation,

London, UK: Routledge.

Marshall, H., 2007. The Global Education Terminology Debate: Exploring Some of the Issues. In

Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th

Edition, online). The SAGE Handbook of Research in

International Education. pp. 108–121. United Kingdom: Routledge. Accessed from:

https://www-dawsonera-com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/9780857023742/ [Accessed 6 July

2016]

McLafferty, C. & Onwuegbuzie, A.J., 2006. A dimensional resolution of the qualitative-quantitative

dichotomy: Implications for theory, praxis, and national research policy. In annual meeting of the

Mid-South Educational Research Association, Birmingham, AL.

McCaig, N.M., 1994. Growing up with a world view: Nomad children develop multicultural skills.

Foreign Service Journal, 9, pp.32–39.

Morais, D.B. & Ogden, A.C., 2011. Initial Development and Validation of the Global Citizenship

Scale. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15(5), pp.445–466.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-74-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

75!

Morales, A., 2015. Factors Affecting Third Culture Kids (TCKs) Transition. Journal of International

Education Research (JIER), 11(1), pp.51–56. Available at:

http://cluteinstitute.com/ojs/index.php/JIER/article/view/9098[Accessed May 1, 2016].

Muller, G.C., 2012. Exploring characteristics of international schools that promote international-

mindedness. Teachers College, Columbia University. Available at:

http://gradworks.umi.com/34/94/3494836.html. [Accessed 6 July 2016]

Murphy, E., 2012. International School Accreditation: Who Needs It? In Hayden, M. & Thompson, J.

International Education, Principles and Practice [Online]. p.212-223. London: Kogan Page.

Available from https://goo.gl/e3SrPs. [Accessed 10 July 2016]

Nieto, S., 2009. Language, Culture, and Teaching: Critical Perspectives, Routledge.

Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AdyNAgAAQBAJ.

Nikel, J. & Lowe, J., 2010. Talking of fabric: a multi!dimensional model of quality in education.

Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 40(5), pp.589–605.

OXFAM. 2016. Global Citizenship Guides [Online]. United Kingdom: Oxfam Education GB.

Available at: http://www.oxfam.org.uk/education/global-citizenship/global-citizenship-guides

[Accessed February 14, 2016a].

Ritzer, G., 1983. The “McDonaldization” of Society. Journal of American culture, 6(1), pp.100–107.

Singh, M. & Qi, J., 2013. 21st century international mindedness: An exploratory study of its

conceptualisation and assessment, University of Western Sydney.

Shields, R., 2015. Measurement and Isomorphism in International Education. In Hayden, M., Levy, J.

& Thompson, J., 2015. The SAGE Handbook of Research in International Education. (7th

Edition). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. pp.477-487.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-75-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

76!

Skelton, M., 2007. International mindedness and the Brain: The Difficulties of" Becoming. The SAGE

handbook of research in international education, pp.379–389.

Skelton, M., 2013. International-mindedness: Martin Skelton examines definitions and issues.

International School Magazine, 15(2), pp.13–14.

Snowball, L., 2007. Becoming more internationally-minded: International teacher certification and

professional development. In Hayden, M., Levy, J. & Thompson, J. (6th Edition, online). The

SAGE Handbook of Research in International Education. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Accessed from: https://www-dawsonera.com.ezproxy1.bath.ac.uk/readonline/ 9780857023742/

[Accessed 6 July 2016] pp.247–255.

Swain, G., 2007. Is a global mindset in your DNA? Thunderbird Magazine, 60, pp.24–30.

Sylvester, B., 1998. Through the lens of diversity: inclusive and encapsulated school missions.

International education: Principles and practice, pp.184–196.

Taylor, S., 2013. A Web Chart of the International Dimension of a School [MA Assignment]. i-

Biology | Reflections. Available at: https://ibiologystephen.wordpress.com/2013/10/03/a-web-

chart-of-the-international-dimension-of-a-school-ma-assignment/ [Accessed February 14, 2016].

Taylor, S., 2015. The IMaGE of an international school. Plan of a small-scale case study to pilot-test a

web chart of the international dimension of a school. [Unpublished MA assignment]

Useem, R.H. & Downie, R.D., 1976. Third-Culture Kids [Online]. Today’s Education. Available at:

http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ157665 [Accessed May 1, 2016].

Van Hook, S.R., 2005. Themes and Images That Transcend Cultural Differences in International

Classrooms. Online Submission. Available at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED490740. [Accessed 6

July 2016]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-76-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor (sjytlr) University of Bath MA Education (International Education)

!

!

77!

Van Hook, S.R., 2011. Modes and models for transcending cultural differences in international

classrooms. Journal of Research in International Education, 10(1), pp.5–27. Available at:

http://jri.sagepub.com/content/10/1/5.abstract. [Accessed 6 July 2016]

Woolf, M., 2005. Avoiding the missionary tendency. International Educator, 14(2), p.27. Available

at: http://search.proquest.com/openview/6a1560b2b205b9d28b515297300f329f/1?pq-

origsite=gscholar. [Accessed 8 May 2016]

Wylie, M., 2008. Internationalizing curriculum: Framing theory and practice in international schools.

Journal of Research in International Education, 7(1), pp.5–19. Available at:

http://jri.sagepub.com/content/7/1/5.abstract.

Yamato, Y., 2003. Education in the market place: Hong Kong’s international schools and their

modes of operation, Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong.

Yemini, M., 2012. Internationalization assessment in schools: Theoretical contributions and practical

implications. Journal of Research in International Education, 11(2), pp.152–164.

Yin, R.K., 2009. Case study research: Design and methods 4th ed. In United States: Library of

Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

Zilber, E., 2009. Third Culture Kids - The Children of Educators in International Schools [Online],

John Catt Educational Ltd. Available from: http://books.google.co.jp/books/about/

Third_Culture_Kids_The_Children_of_Educa.html? hl=&id=SOjzeqaFEA0C. [Accessed 6 July

2016]

Zschokke, S. & Vollrath, F., 1995. Web construction patterns in a range of orb-weaving spiders

(Araneae). European journal of entomology, 92(3), pp.523–541.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-77-320.jpg)

![!

93!

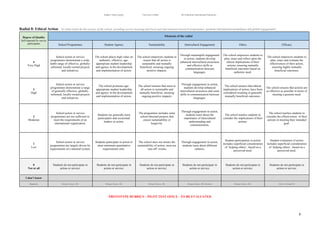

Appendix 4: Participant Rubric Responses (Raw Data)

The following tables present the raw collected data for the surveys, including pre-test ratings, ratings

for individual elements of each radial, overall ‘best-fit’ratings for each radial and a feedback rating on

the clarity of the radial’s descriptors. Also included: mean and standard deviation data for each rating,

based on (n=10), along with t-test significance date (P=0.05) for comparison between pre-test and

best-fit radials for each radial. Finally, notes and observations obtained through the survey feedback

questionnaire and follow-up discussions have been transcribed under the appropriate sections.

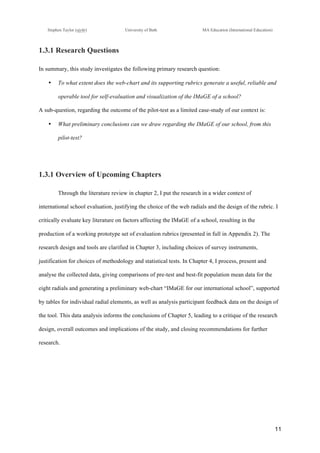

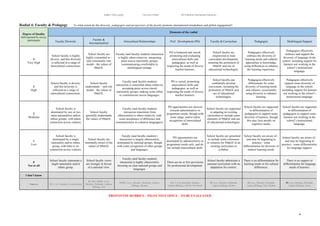

Radial 1: Values & Ideology (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Mission & Vision, Core Values & Rules] But not clear whether the mission and core values

are being followed.”

●! “[Access languages] The ‘Low’ (1) descriptor is mistakenly a repeat of the ‘Moderate’ (2)

descriptor”

●! “[Access languages] Two of the descriptors are the same.” (clarified in conversation - level 1

was an error.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-91-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor MA International Education Dissertation Drafting!

How international is our school? Pilot-testing a web-chart of the international dimensions of a school. !

98!

Radial 2: leadership, Policy & Governance (n=10)

Note the high number of ‘I don’t know’ responses for this radial.

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Recruitment] [Responded ‘I don’t know’] Believe that admin looks for ‘best fit’ for the job

regardless of nationality.

●! “[Leadership diversity] “host nationality and nominal culture” should be reversed.

Radial 3: Students & Transition (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Overall] It seems like ‘transition’ doesn’t fit in here.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-92-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor MA International Education Dissertation Drafting!

How international is our school? Pilot-testing a web-chart of the international dimensions of a school. !

98!

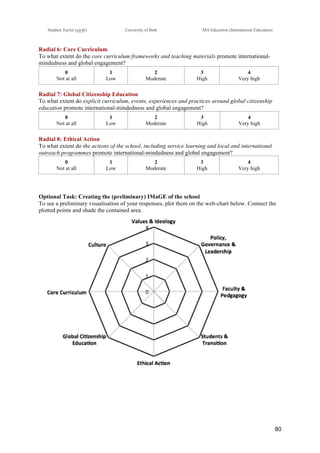

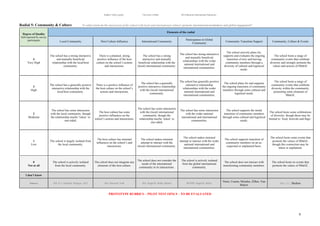

Radial 4: Faculty & Pedagogy (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Pedagogies] happens a more in elementary school than secondary school.”

●! “[Differentiation for multilingual support] really depends on the course. Langauge courses

seem to be better.”

Radial 5: Community & Culture (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Participation in global communities] this seems to happen by individuals more than by the

school?”

●! “[Participation in global communities] We have a strong tie with international community in

volunteering and entertainment (music, bands, choir, etc), but no yet strong in international

academic or science competition (besides a few like math olympiad etc)

●! “[Participation in global communities] we could improve in this area some more.”

●! “[Community, culture & events] we do somewhat, could do more.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-93-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor MA International Education Dissertation Drafting!

How international is our school? Pilot-testing a web-chart of the international dimensions of a school. !

98!

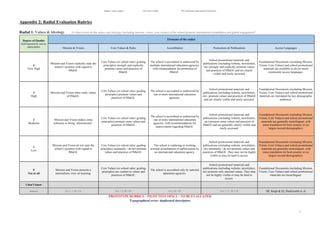

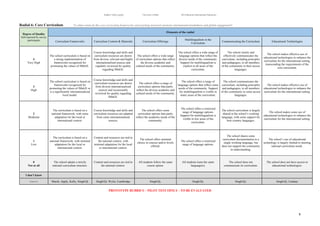

Radial 6: Core Curriculum (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Communicating the Curriculum] Seen more later in the year with parent evening for

families in multi-languages.”

●! “[Overall] I expected to rate this more highly overall, (as we’re an IB World School).”

Radial 7: Global Citizenship Education (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Educational technology (responded ‘don’t know’] Not sure what this strand means.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-94-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor MA International Education Dissertation Drafting!

How international is our school? Pilot-testing a web-chart of the international dimensions of a school. !

98!

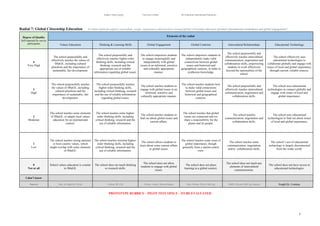

Radial 8: Ethical Action (n=10)

Volunteer comments:

●! “[Overall] The school seems to be engaging in more globally-informed programs, but still

doesn’t always look @ long-term sustainability (island clean-ups causing more garbage than

is picked up)

●! “Service learning is stronger, where local and international outreach programmes are

weaker.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-95-320.jpg)

![!

Stephen Taylor MA International Education Dissertation Drafting!

How international is our school? Pilot-testing a web-chart of the international dimensions of a school. !

98!

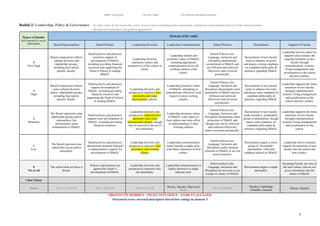

Optional comments on the purpose and clarity of the chart:

•! “Would a graph presentation be more clear? Like how we do ATLs (approaches to learning) on

the report card?” (Note: refers to a bar chart).

•! “Add some colours to the web chart.”

•! “Strong visual when matched with the rubric to describe the fine points of the ideas/ concepts.”

•! “This is useful for any parents who are looking for an “excellent” international school”

•! “The web can be used like a logo mark next to the school [on a website/brochure]”

•! “I have never seen any rubric for internationalism, so it’s about time that the public is exposed to

this kind of rubric.”

•! “I am used to seeing these - not sure if it is common outside academia.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylordisspublic-170115052914/85/How-International-Is-Our-School-MA-Dissertation-97-320.jpg)