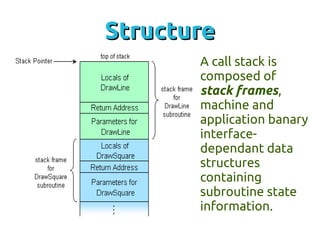

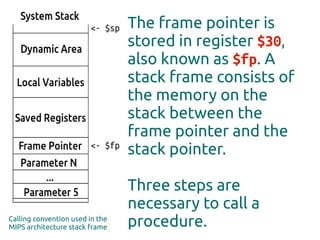

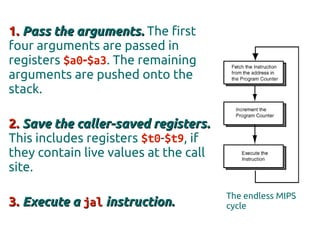

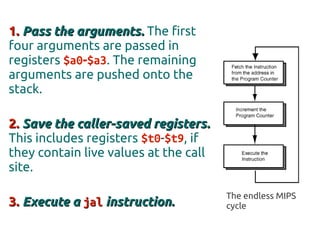

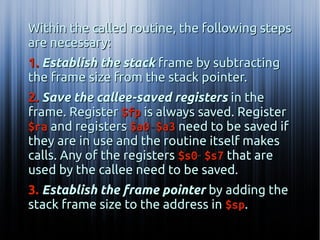

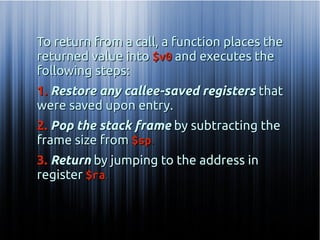

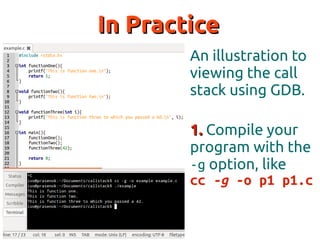

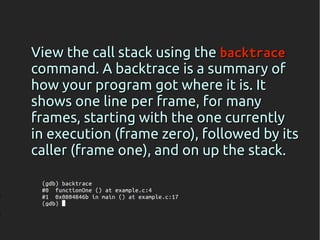

The call stack is a data structure that stores information about active subroutines in a computer program. It keeps track of the point to which each subroutine should return control when finished. Subroutines can call other subroutines, resulting in information stacking up on the call stack. The call stack is composed of stack frames containing state information for each subroutine. Debuggers like GDB allow viewing the call stack to see how the program arrived at its current state.