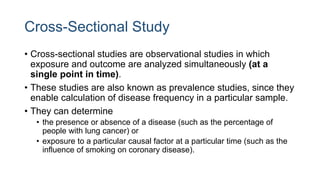

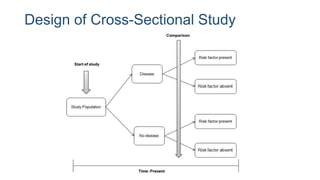

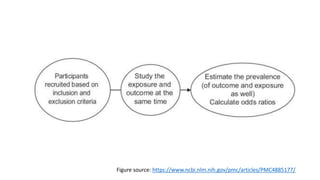

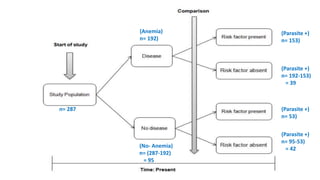

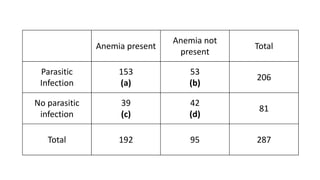

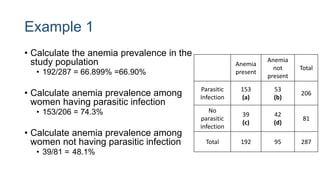

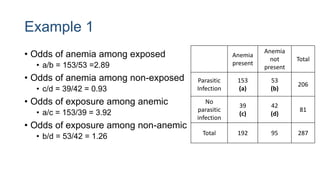

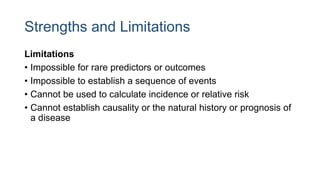

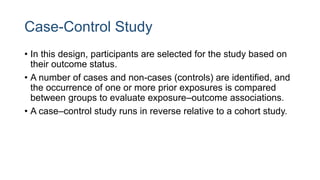

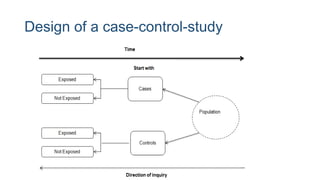

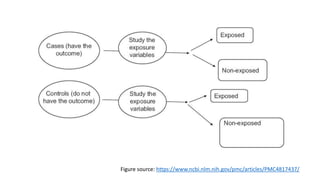

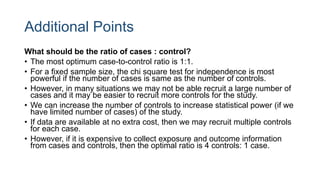

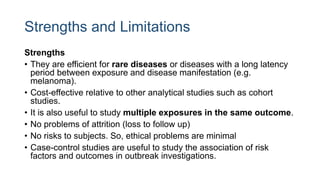

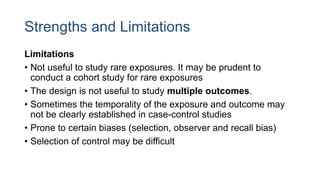

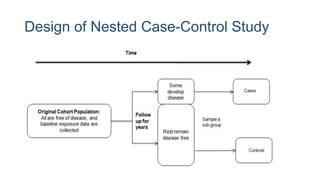

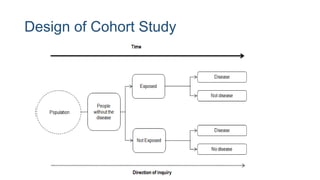

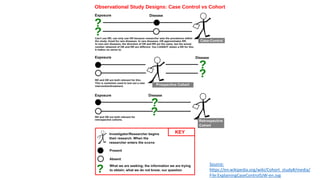

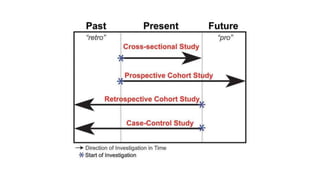

The document outlines various study designs used in research, particularly focusing on observational analytical methods such as cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies. It details their structures, strengths, limitations, and applications, providing specific examples like assessing anemia prevalence in pregnant women. The document emphasizes the importance of study design choice based on the research objective, outcomes, and population characteristics.