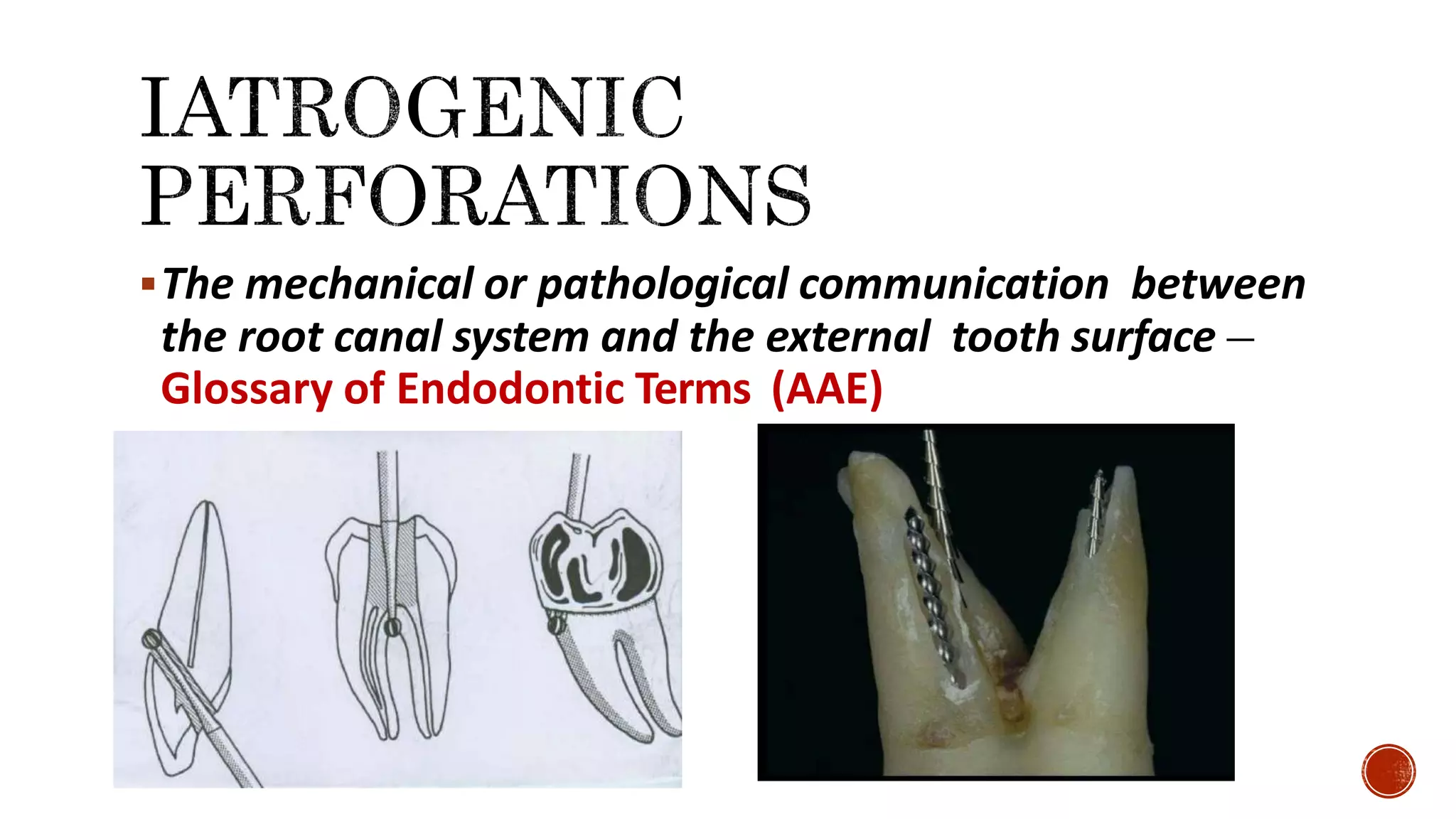

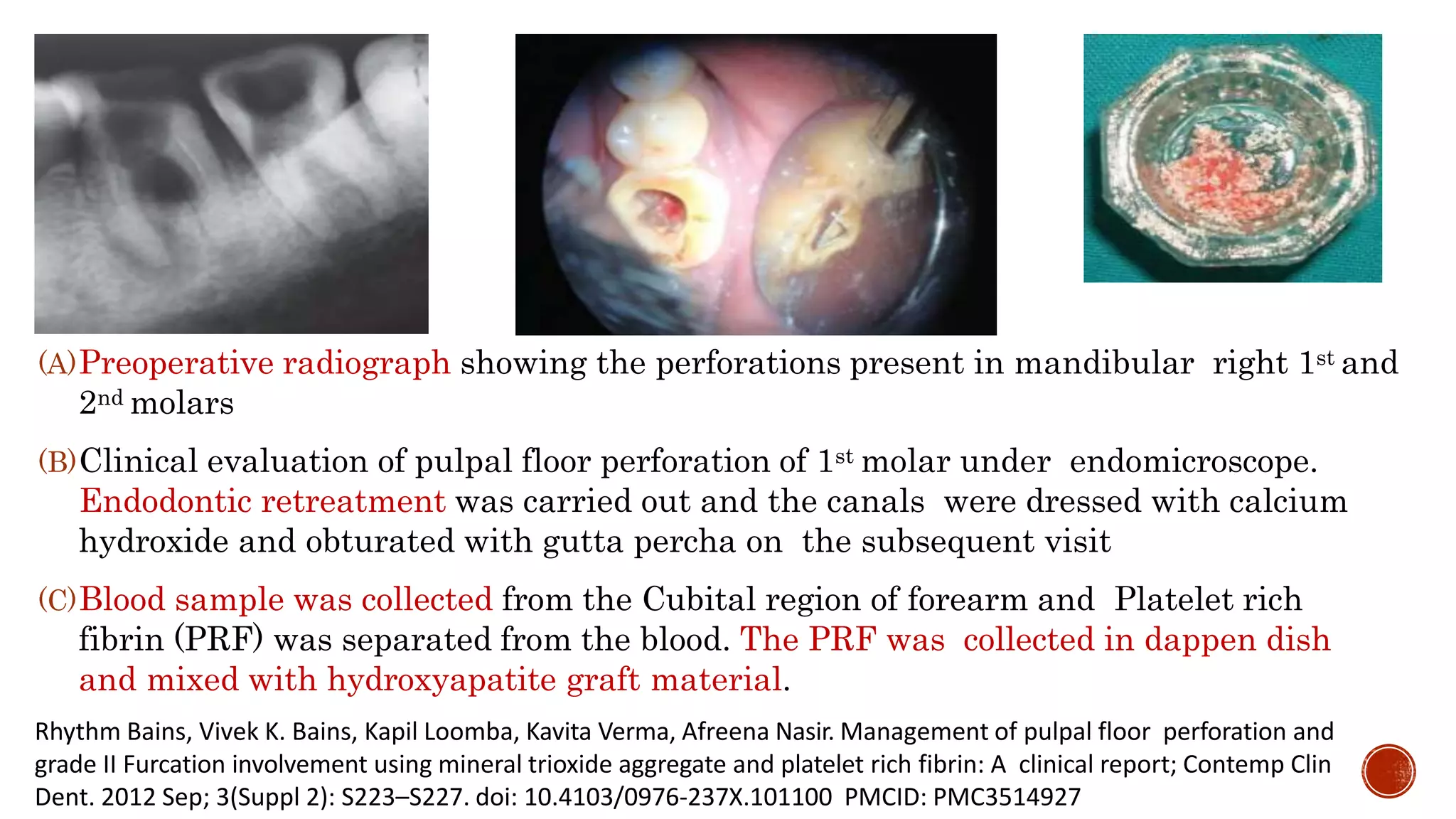

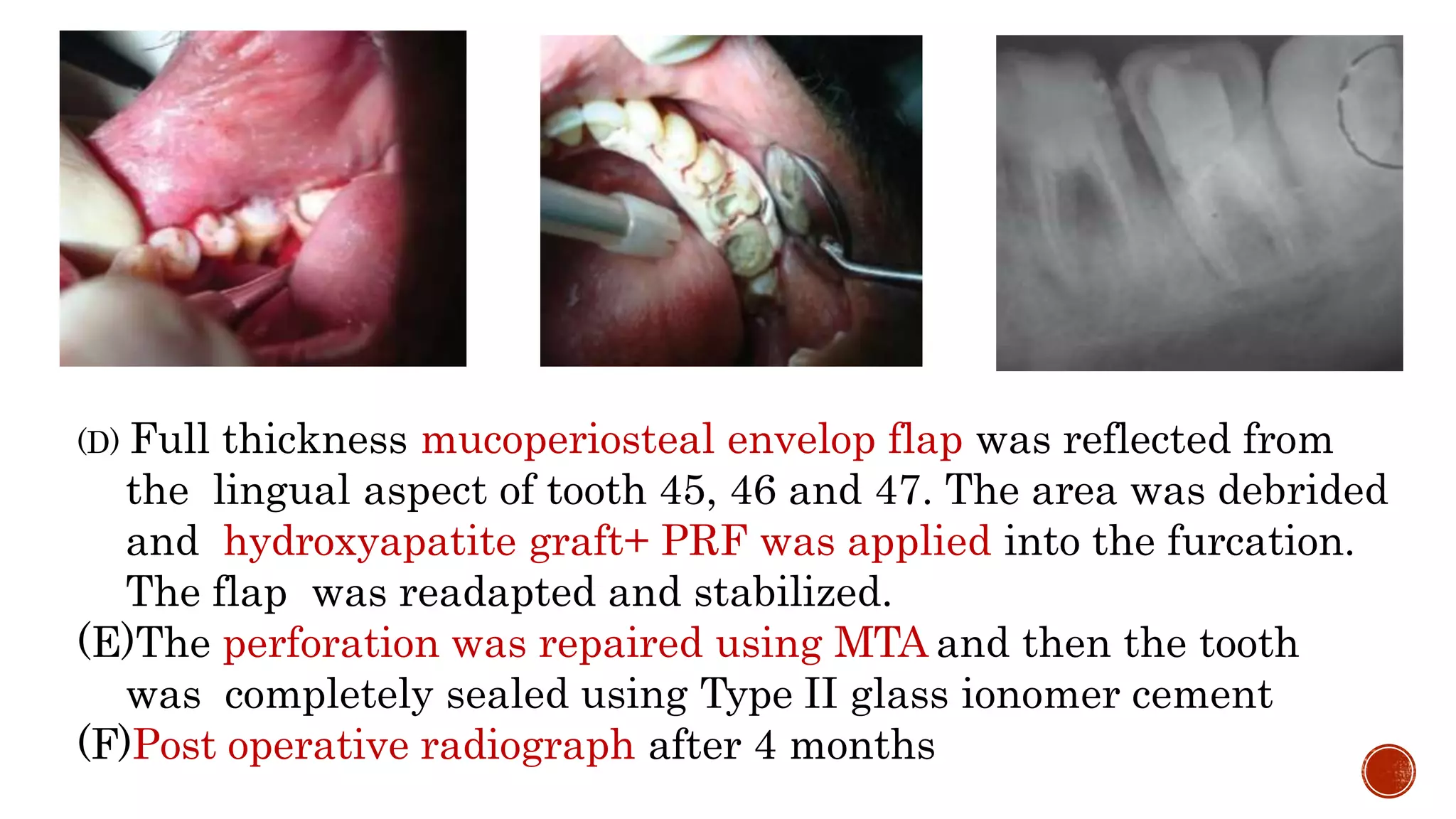

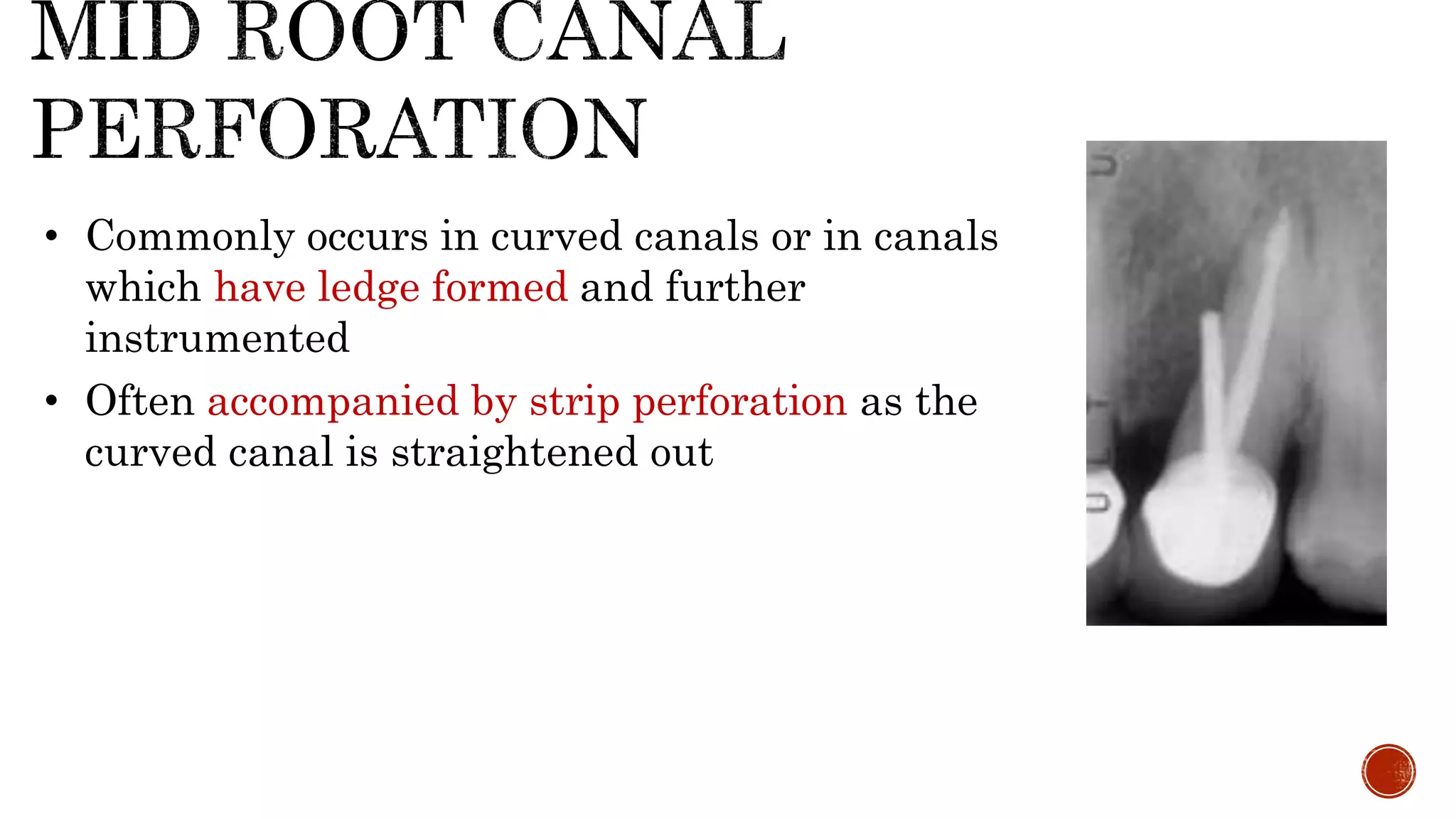

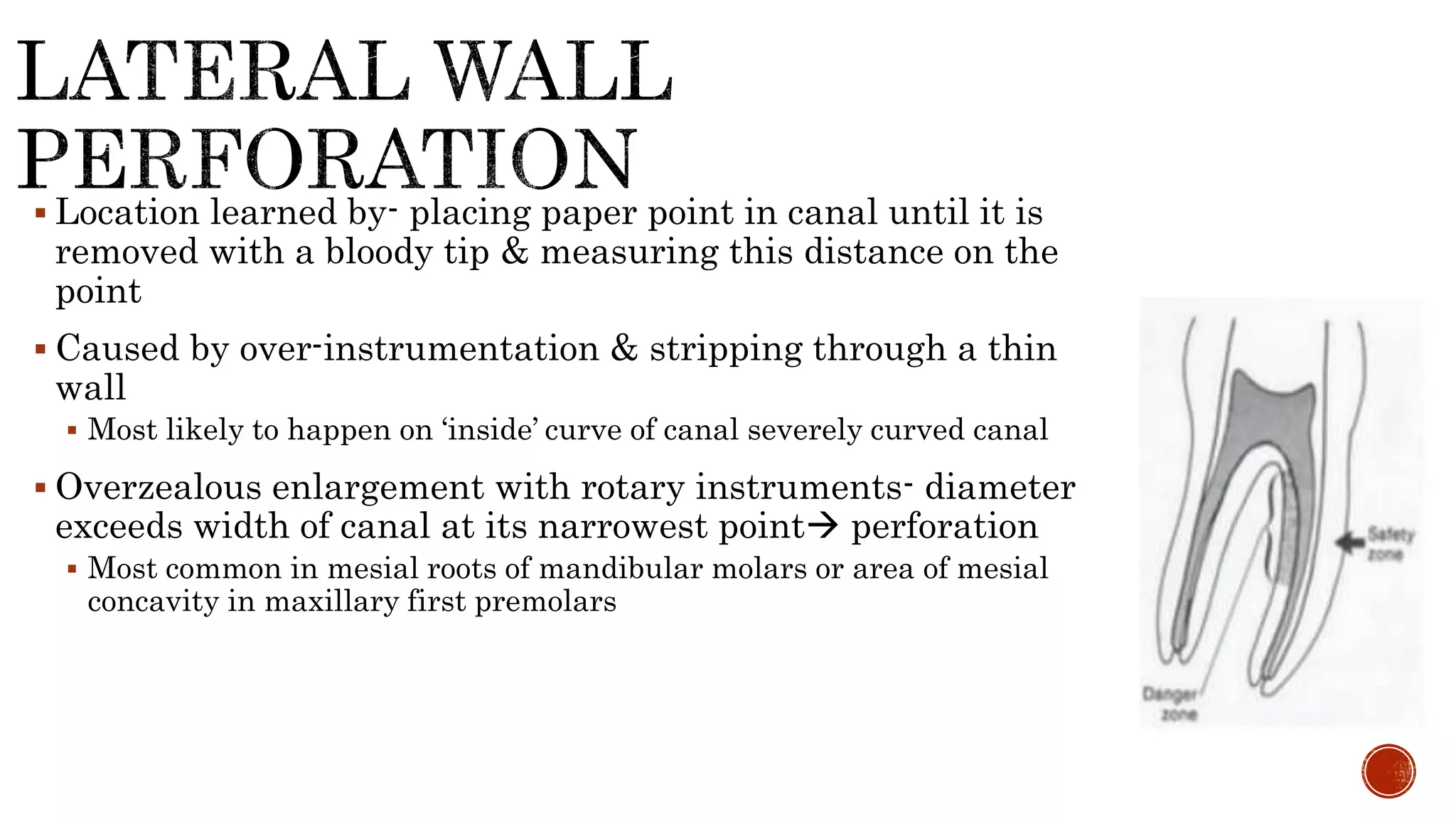

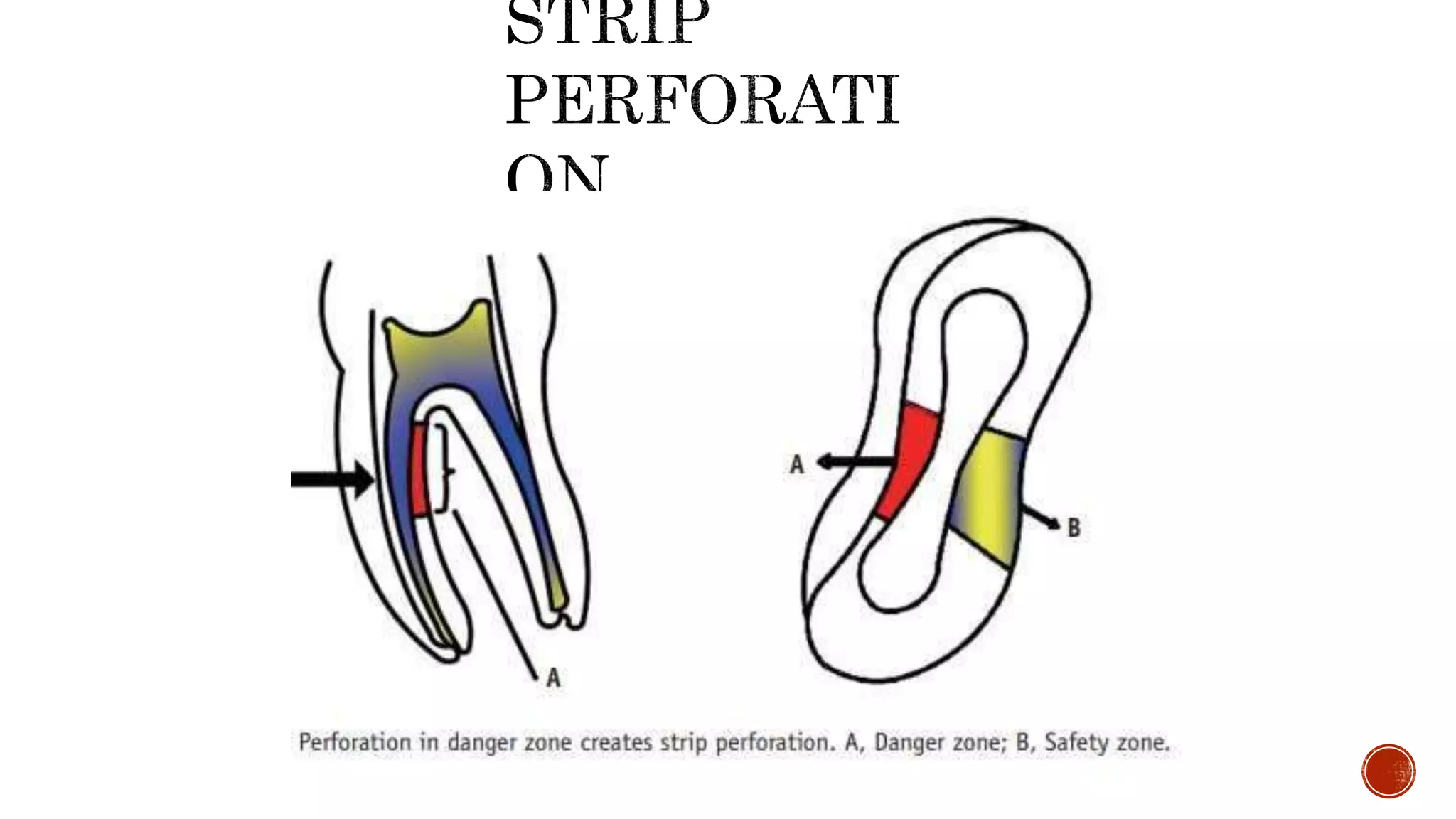

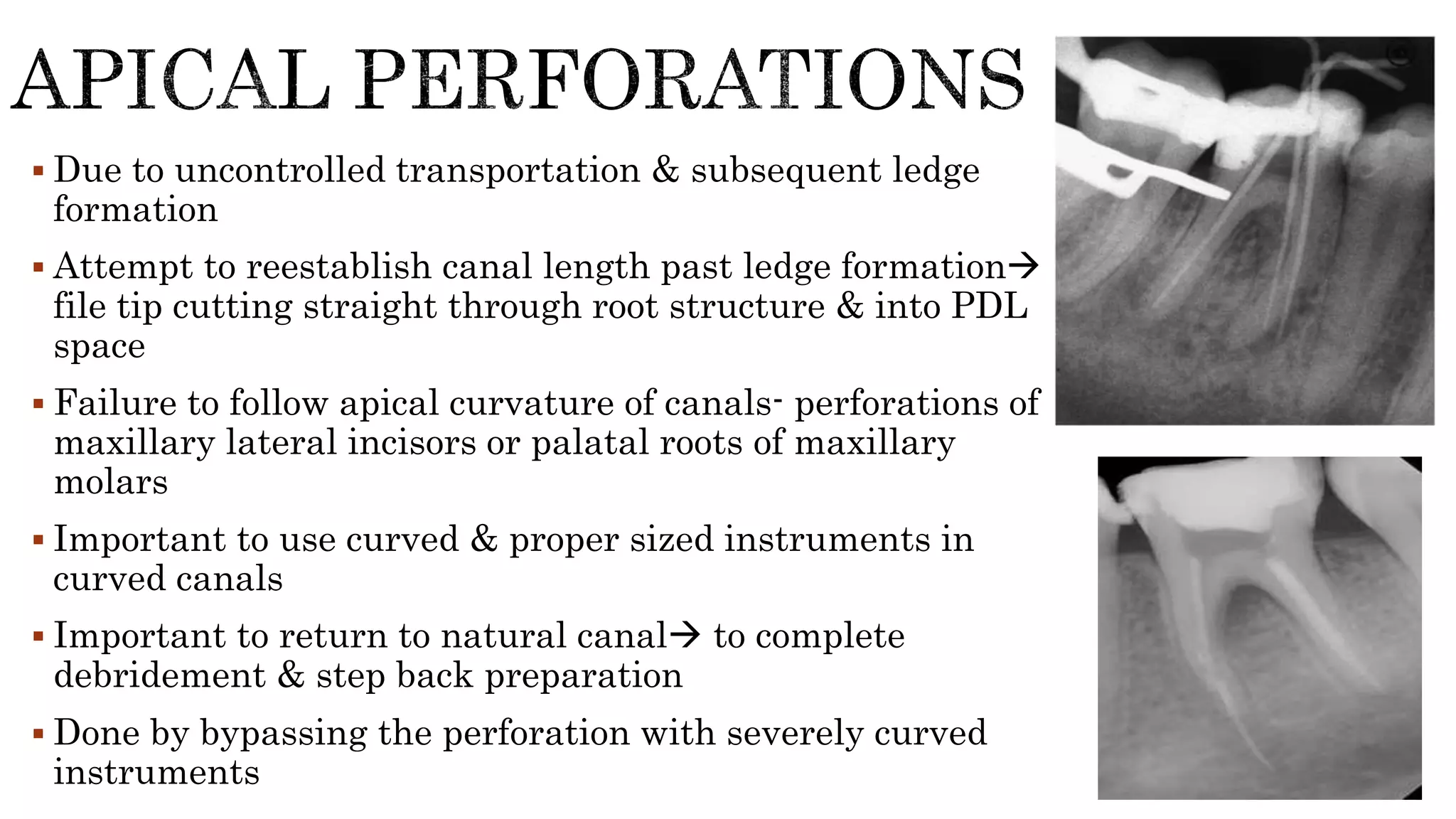

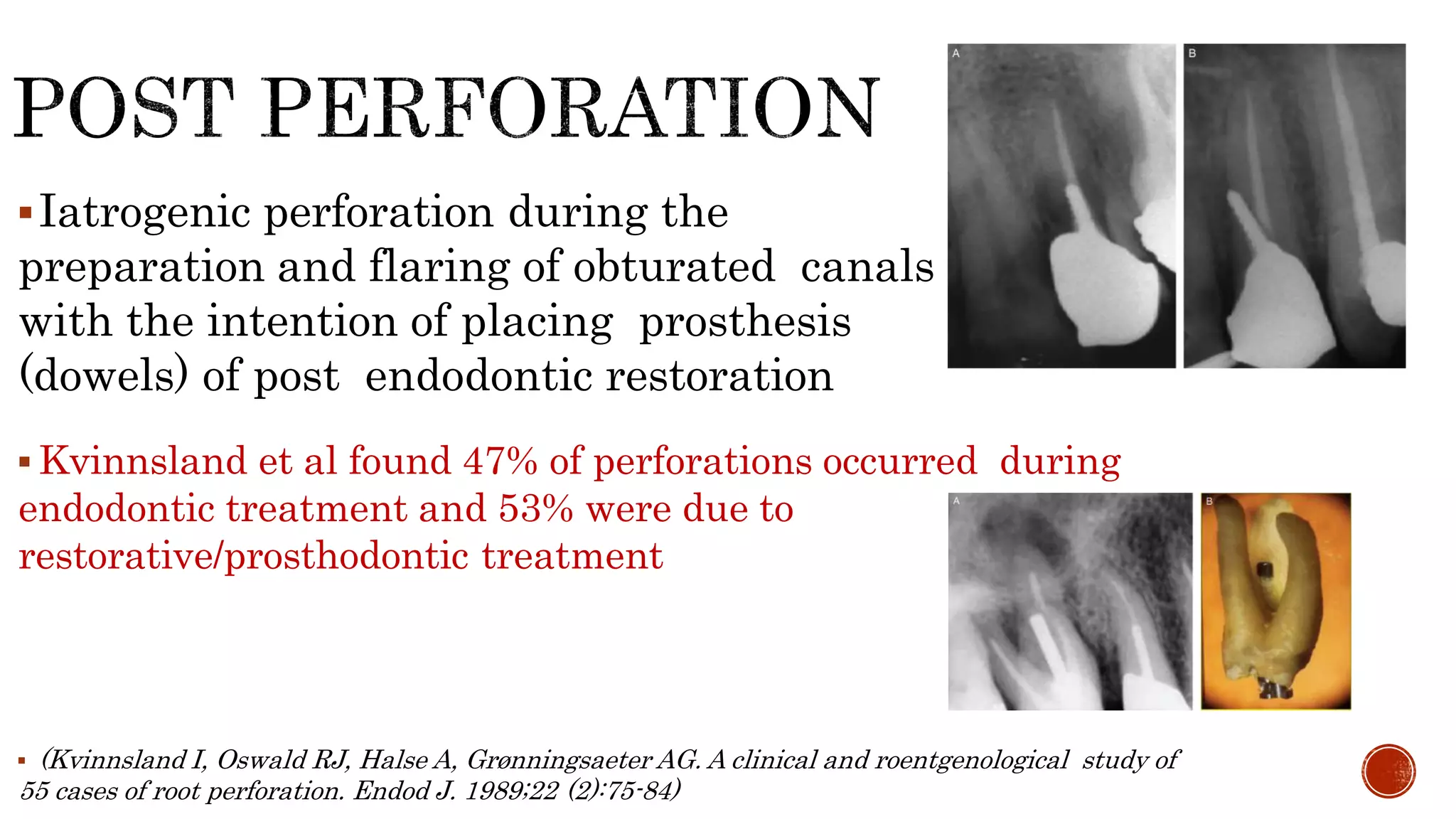

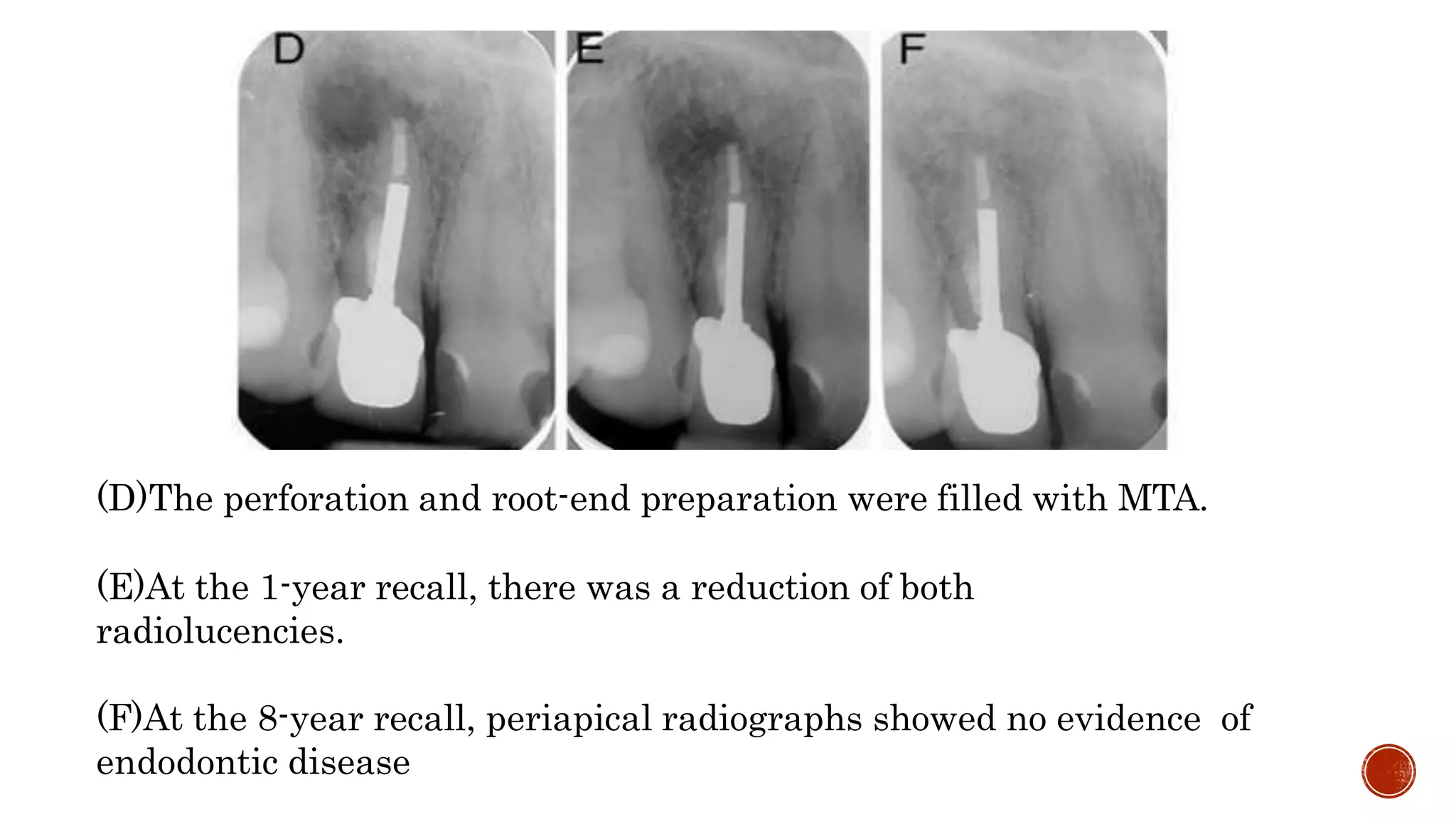

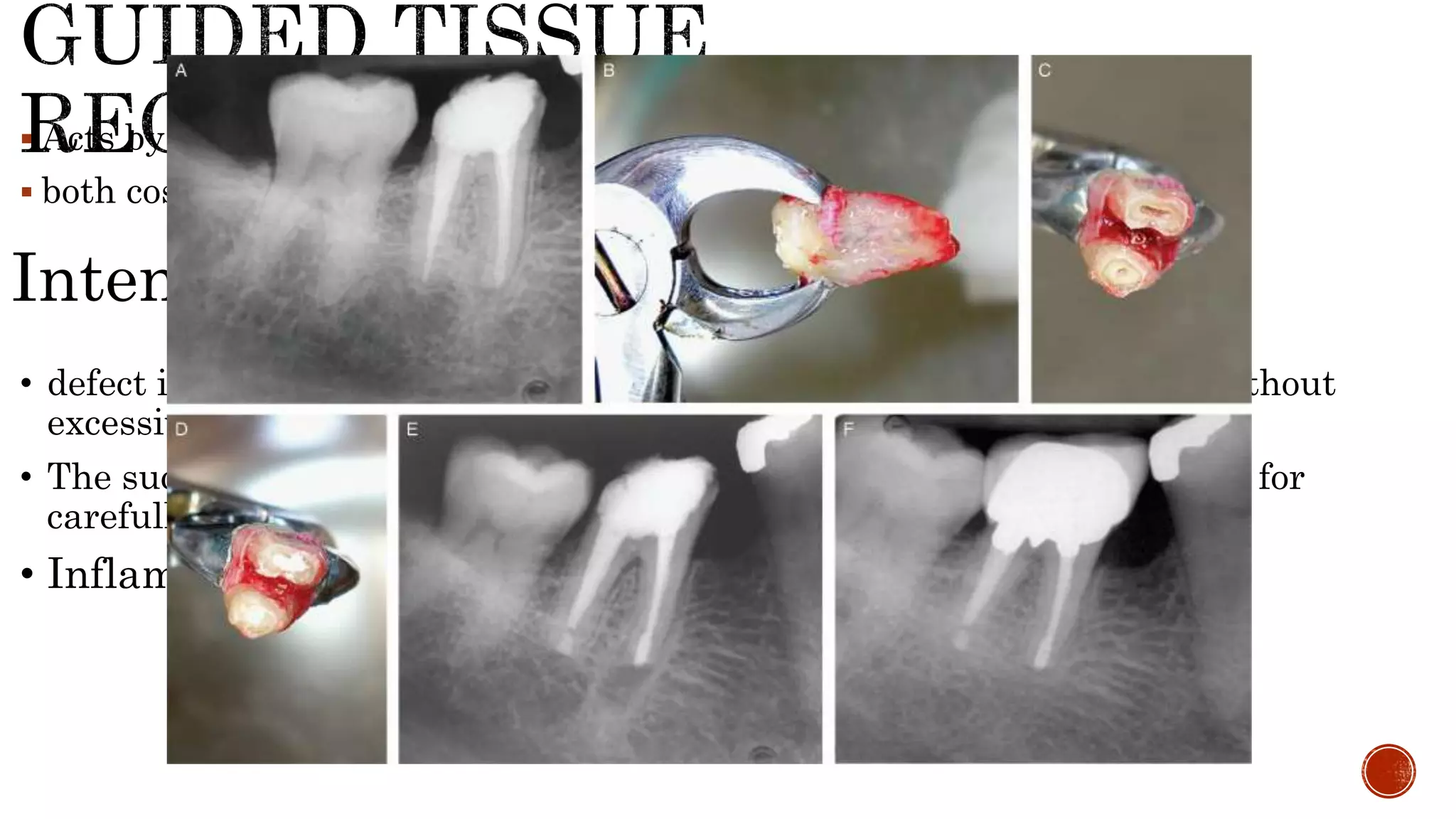

The document discusses various types of iatrogenic root perforations in dentistry, outlining their predisposing factors, classifications, and treatment approaches. It emphasizes the importance of timely intervention, the prognosis related to the size and location of perforations, and the use of specific sealing materials for effective repair. Additionally, it highlights preventive measures and the consequences of improper instrumentation methods during endodontic procedures.