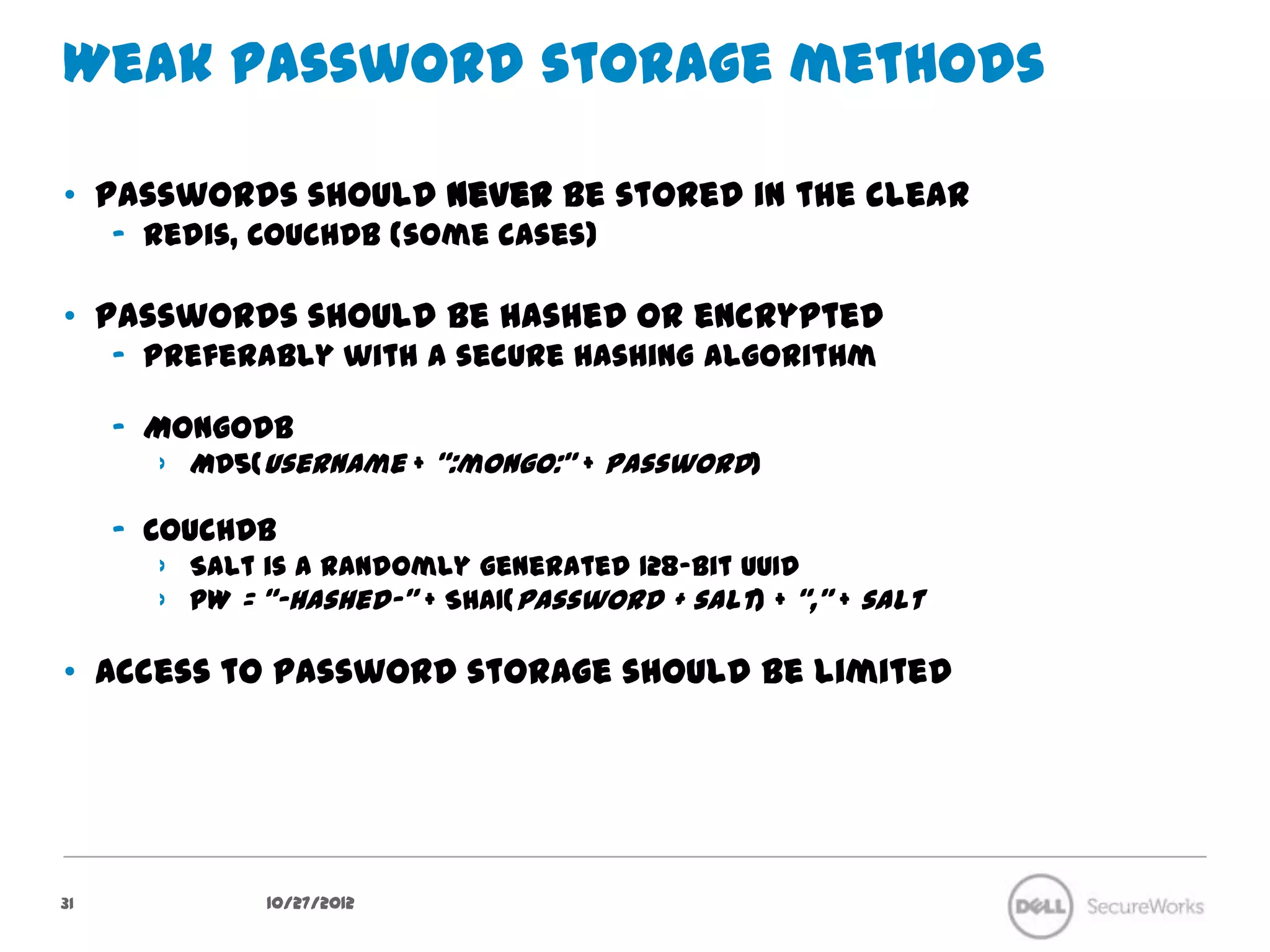

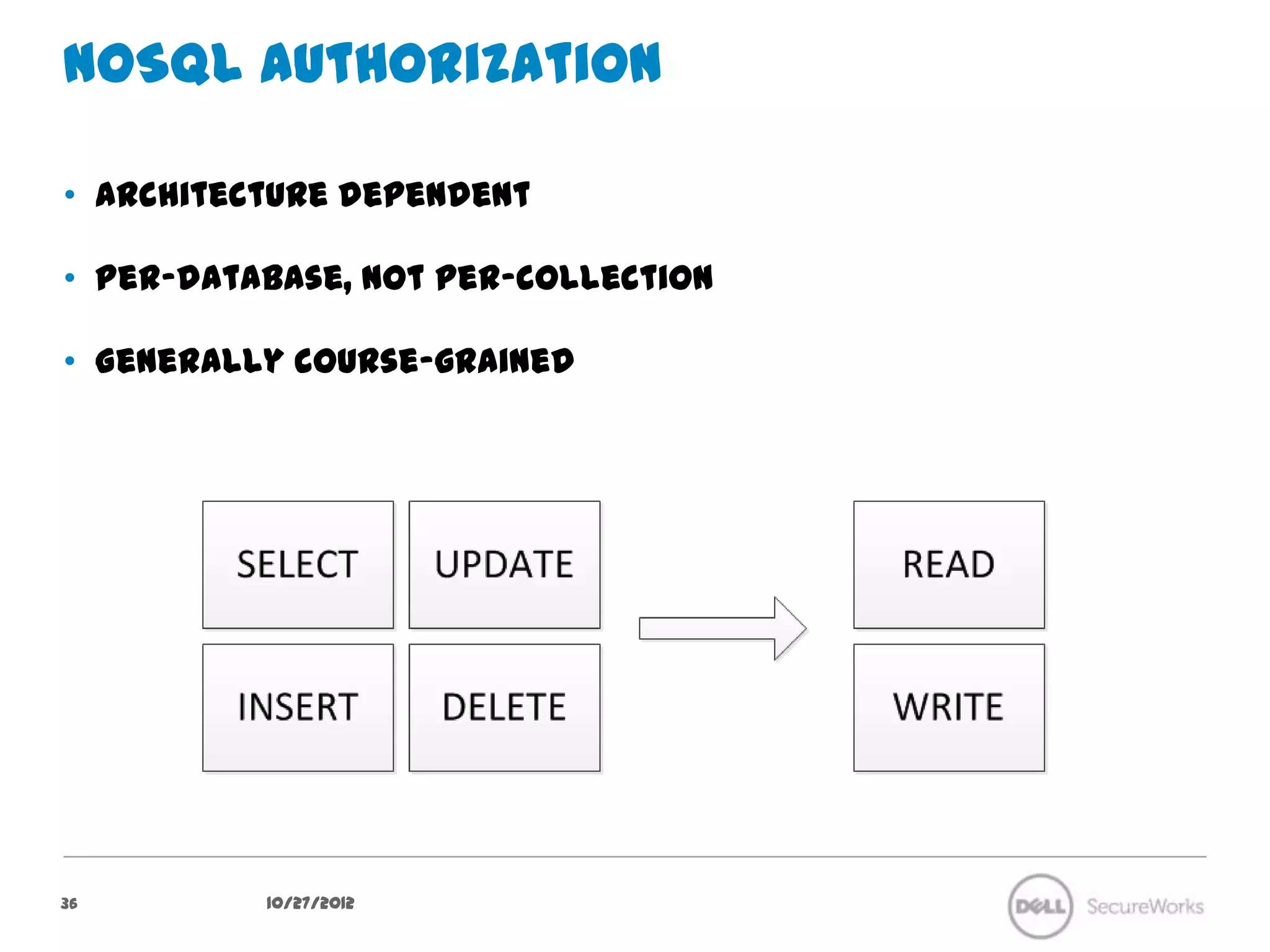

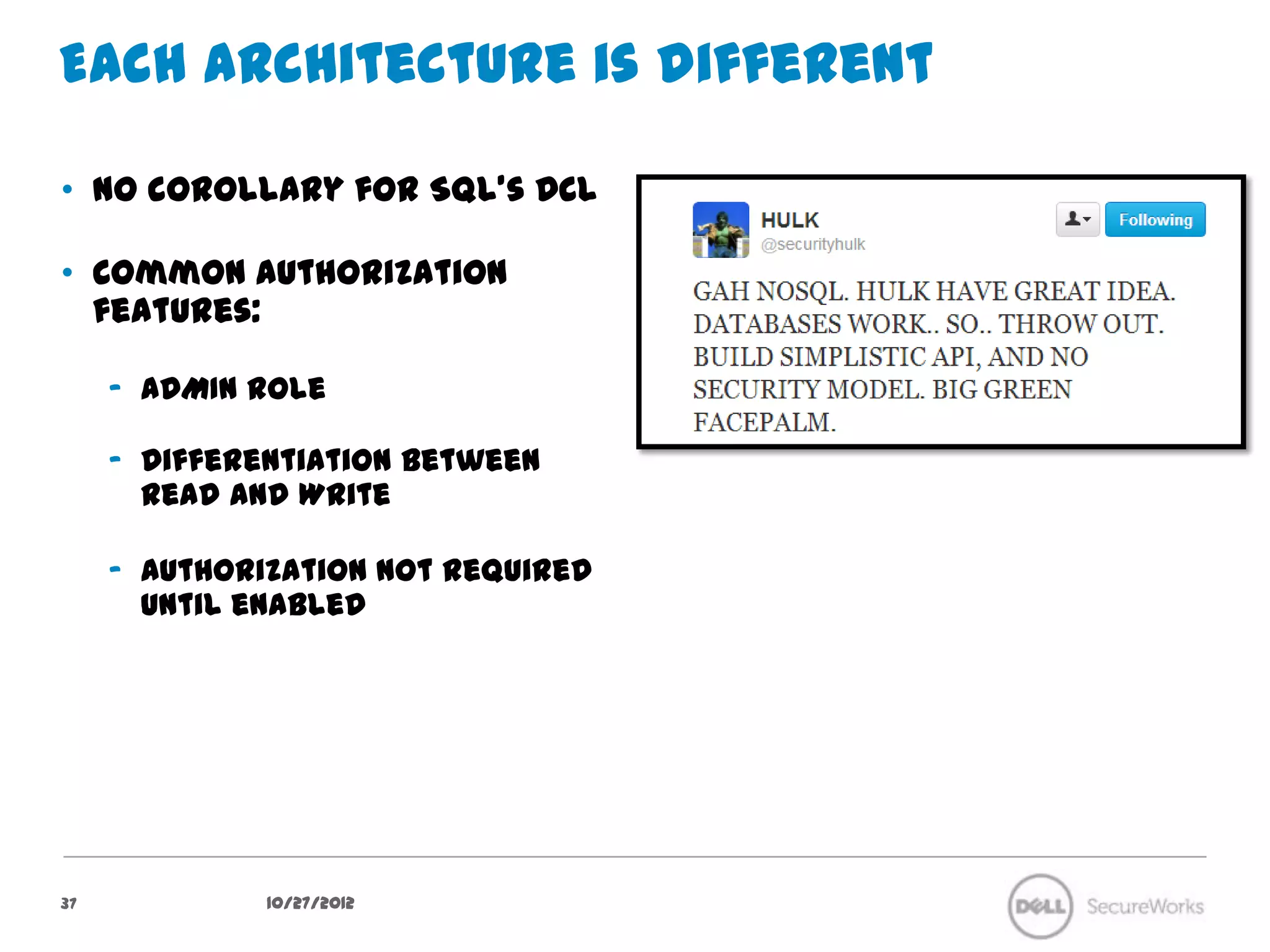

The document discusses security concerns regarding NoSQL databases. It covers common attack vectors like injection attacks that can affect both relational and NoSQL databases. It then focuses on specific issues in securing NoSQL deployments, including weak authentication methods, insecure password storage, lack of authorization support, and lack of confidentiality measures. The document advocates approaches like input validation, access control, and encryption to help mitigate risks in NoSQL systems.

![“Redis is designed to be accessed by trusted clients inside trusted

environments. This means that usually it is not a good idea to expose

the Redis instance directly to the internet or, in general, to an

environment where untrusted clients can directly access the Redis TCP

port or UNIX socket.” [redis.io]

5 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-5-2048.jpg)

![“The most effective way to reduce risk for MongoDB deployments is to

run your entire MongoDB deployment, including all MongoDB

components in a trusted environment” [mongodb.org]

6 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-6-2048.jpg)

![“When you start out fresh, CouchDB allows any request to be made by

anyone. [..] it should be obvious that putting a default installation into

the wild is adventurous. Any rogue client could come along and delete

a database.” [guide.couchdb.org]

7 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-7-2048.jpg)

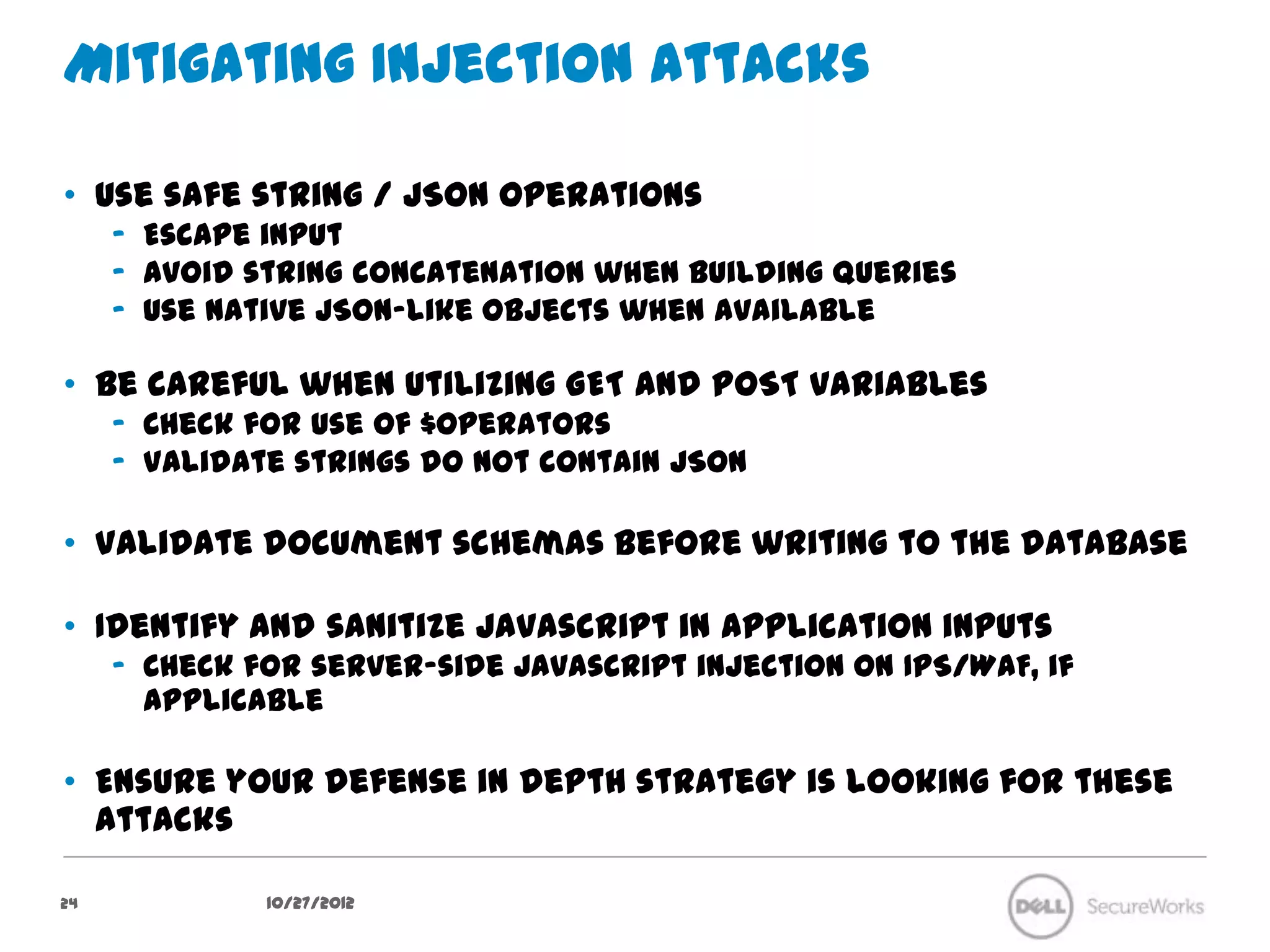

![PHP’s Superglobals

• PHP automatically converts superglobal values to multidimensional

arrays

– $_POST – for working with HTTP POST data

– $_GET – for working with HTTP GET data

• This is very handy when working with web forms

– <input type=“text” name=“person[name]” value=“”>

– Can be referenced via $_POST[‘person’][‘name’]

• PHP also uses arrays to represent MongoDB documents

– $user = array(

‘email' => ‘will@localhost',

‘password' => ‘mmmfrenchtoast',

‘date_created' => ‘2012-06-15’

);

21 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-21-2048.jpg)

![PHP’s Superglobals

• Adversaries can weaponize superglobals by inserting MongoDB

comparison operations in HTTP GET or POST keys

– forgot_password.php?

email=will@localhost&security_question[$ne]=1

– Array (

“email” => “will@localhost”,

“security_question” => array(“$ne” => 1)

);

• Kudos to Bryan Sullivan @ Adobe for identifying and reporting this

http://blogs.adobe.com/asset/files/2011/04/NoSQL-But-Even-Less-Security.pdf

22 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-22-2048.jpg)

![Local-only security model

• “When you start out fresh, CouchDB allows any request to be made

by anyone. [..] Everybody has privileges to do anything.

Neat.” [guide.couchdb.org]

• “If there are no admin users, one may access the database from the

localhost interface without authenticating.” [mongodb.org]

• Limited security by default

• Localhost only

• Rapid development

• Ease of use

• Growing pains

• Authentication methods don’t always effectively scale beyond localhost

27 10/27/12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nosqlnosecurityr2-121026152208-phpapp01/75/NoSQL-no-security-27-2048.jpg)