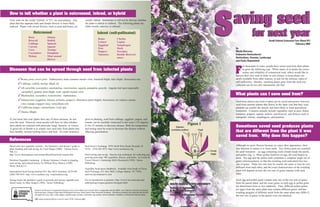

The document provides guidance on saving seeds from various plants, focusing on the benefits of seed saving such as cost savings and self-sufficiency. It explains the differences between inbred, outcrossed, and hybrid plants, including how genetic variations affect seed characteristics and the challenges in ensuring seed purity. Additionally, it offers tips for selecting healthy plants and methods for harvesting and storing seeds to minimize disease risks.