This document discusses various properties and concepts related to the z-transform, which is used to analyze discrete-time signals. It defines the z-transform and region of convergence. It then provides examples of calculating the z-transform for different signals. Key properties discussed include time shifting, scaling, time reversal, differentiation, and convolution. Theorems regarding the initial value and final value are also covered. Worked examples are provided to demonstrate applying the various properties and concepts.

![2

The Direct Z-Transform

The z-transform of a discrete time signal is defined as the power

series

(1)

Where z is a complex variable. For convenience, the z-transform of a

signal x[n] is denoted by

X(z) = Z{x[n]}

Since the z-transform is an infinite series, it exists only for those

values of z for which this series converges. The Region of

Convergence (ROC) of X(z) is the set of all values of z for which

this series converges.

We illustrate the concepts by some simple examples.

n

n

z

]

n

[

x

)

z

(

X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-2-2048.jpg)

![3

Example 1: Determine the z-transform of

the following signals

(a) x[n] = [1, 2, 5, 7, 0, 1]

Solution: X(z) = 1 + 2z-1+ 5z-2 + 7z-3 + z-5,

ROC: entire z plane except z = 0

(b) y[n] = [1, 2, 5, 7, 0, 1]

Solution: Y(z) = z2 + 2z + 5 + 7z-1 + z-3

ROC: entire z-plane except z = 0 and z = .

(c) z[n] = [0, 0, 1, 2, 5, 7, 0, 1]

Solution: z-2 + 2z-3 + 5z-4 + 7z-5 + z-7, ROC: all z except z=0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-3-2048.jpg)

![4

(d) p[n] = [n]

Solution: P(z) = 1, ROC: entire z-plane.

(e) q[n] = [n – k], k > 0

Solution: Q(z) = z-k, entire z-plane except

z=0.

(f) r[n] = [n+k], k > 0

Solution: R(z) = zk,

ROC: entire z-plane except z = .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-4-2048.jpg)

![5

Example 2: Determine the z-transform of

x[n] = (1/2)nu[n]

Solution:

ROC: |1/2 z-1| < 1, or equivalently |z| > 1/2

1

2

1

n

0

n

1

n

n

0

n

n

n

z

2

1

1

1

.......

z

2

1

z

2

1

1

z

2

1

z

2

1

z

]

n

[

x

)

z

(

X

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-5-2048.jpg)

![6

Example 3: Determine the z-transform of the

signal x[n] = anu[n]

Solution:

|

a

|

|

z

:|

ROC

az

1

1

.......

az

az

1

az

z

a

)

z

(

X

1

2

1

1

n

0

n

1

n

0

n

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-6-2048.jpg)

![7

Properties of z-transform

Linearity

If x1[n] X1(z)

and x2[[n] X2(z)

then

a1x1[n] + a2x2[n] a1X1(z) + a2X2(z)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-7-2048.jpg)

![8

Example: Determine the z-transform of

the signal x[n] = [3(2n) – 4(3n)]u[n]

Solution:

1

1

n

n

1

n

z

3

1

1

4

z

2

1

1

3

]

3

4

)

2

(

3

[

z

az

1

1

]]

n

[

u

a

[

z

Example 4: Determine the z-transform of

the signal (cosw0n)u[n]

2

0

1

0

1

1

jw

1

jw

0

n

jw

n

jw

0

z

w

cos

z

2

1

w

cos

z

1

z

e

1

1

2

1

z

e

1

1

2

1

]

n

[

u

n

w

cos

z

e

2

1

e

2

1

]

n

[

u

n

w

cos

0

0

0

0

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-8-2048.jpg)

![9

Time Shifting Property:

If x[n] X(z) then x[n-k] z-kX(z)

Proof:

since

then the change of variable m = n-k

produces

n

n

z

]

k

n

[

x

]]

k

n

[

x

[

z

)

z

(

X

z

z

]

m

[

x

z

z

]

m

[

x

]]

k

n

[

x

[

z

k

m

m

k

m

)

k

m

(

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-9-2048.jpg)

![10

Example: Find the z-transform of a unit step

function. Use time shifting property to find z-

transform of u[n] – u[n-N].

The z-transform of u[n] can be found as

Now the z-transform of u[n]-u[n-N] may be

found as follows:

1

2

1

0

n

n

n

n

z

1

1

.......

z

z

1

z

z

]

n

[

u

]]

n

[

u

[

z

1

N

1

N

1

z

1

z

1

z

1

1

z

z

1

1

]]

N

n

[

u

]

n

[

u

[

z

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-10-2048.jpg)

![11

Scaling in the z-domain

If x[n] X(z)

Then anx[n] X(a-1z)

For any constant a, real or complex.

Proof:

Example 5: Determine the z-transform of the signal

an(cosw0n)u[n].

Solution: since

z

a

X

z

a

]

n

[

x

z

]

n

[

x

a

]

n

[

x

a

z 1

n

n

1

n

n

n

n

2

0

1

0

1

0

z

w

cos

z

2

1

w

cos

z

1

]

n

[

u

)

n

w

[cos(

z

2

2

0

1

0

1

0

n

z

a

w

cos

az

2

1

w

cos

az

1

]]

n

[

u

n

w

cos

a

[

z

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-11-2048.jpg)

![12

Time reversal

If x[n] X(z) then x[-n] X(z-1)

Proof:

Example 6: Determine the z-transform of

u[-n].

Solution: since z[u[n]] = 1/(1 – z-1)

Therefore,

Z[u[-n]] = 1/(1-z)

m m

1

m

1

m

n

n

)

z

(

X

z

]

m

[

x

z

]

m

[

x

z

]

n

[

x

]]

n

[

x

[

z](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-12-2048.jpg)

![13

Differentiation in the z - Domain

x[n] X(z) then nx[n] = -z(dX(z)/dz)

Tutorial 4: Q1: Prove the differentiation

property of z – transform.

Example 7: Determine the z-transform of the

signal x[n] = nanu[n].

Solution:

2

1

1

1

n

1

n

az

1

az

az

1

1

dz

d

z

]]

n

[

u

na

[

z

az

1

1

]]

n

[

u

a

[

z

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-13-2048.jpg)

![14

Convolution of two sequences

If x1[n] X1(z) and x2[n] X2(z) then

x1[n]*x2[n] X1(z)X2(z)

Proof:

The convolution of x1[n] and x2[n] is defined as

k

2

1

2

1 ]

k

n

[

x

]

n

[

x

]

n

[

x

*

]

n

[

x

]

n

[

x

The z-transform of x[n] is

n

n

n

2

1

n

n

z

k

n

x

]

k

[

x

z

]

n

[

x

)

z

(

X

Upon interchanging the order of the summation

and applying the time shifting property, we obtain

z

X

z

X

z

]

k

[

x

z

X

z

k

n

x

k

x

)

z

(

X 1

k

2

k

1

2

n

n

2

k

1

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-14-2048.jpg)

![15

Example 8: Compute the convolution

of the signals x1[n] = [1, -2, 1] and

Solution:

X1(z) = 1 – 2z-1 + z-2

X2(z) = 1 + z-1 + z-2 + z-3 + z-4 + z-5

Now X(z) = X1(z)X2(z) = 1 – z-1 – z-6 + z-7

Hence x[n] = [1, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, -1, 1]

Note: You should verify this result from the

definition of the convolution sum.

elsewhere

,

0

5

n

0

,

1

]

n

[

x2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-15-2048.jpg)

![16

Correlation of two sequences

If x1[n] X1(z) and x2[n] X2(z)

then rx1x2[k] = X1(z)X2(z-1)

Tutorial 4 Q2: Prove this property.

The Initial Value Theorem:

If x[n] is causal then )

z

(

X

lim

]

0

[

x

z

Proof:

....

z

]

2

[

x

z

]

1

[

x

]

0

[

x

z

]

n

[

x

)

z

(

X 2

1

0

n

n

Obviously, as z , z-n 0 since n >0, this

proves the theorem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-16-2048.jpg)

![17

Final Value Theorem

If x[n] X(z), then )

z

(

X

z

1

lim

]

[

x 1

1

z

Tutorial 4 Q3: Prove the Final Value

Theorem

Example 9: Find the final value of

2

1

1

z

8

.

0

z

8

.

1

1

z

2

)

z

(

X

Solution: 2

1

1

1

1

z

8

.

0

z

8

.

1

1

z

2

z

1

)

z

(

X

z

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

z

5

.

0

1

z

2

z

5

.

0

1

z

1

z

2

z

1

The final value theorem yields

10

2

.

0

2

z

8

.

0

1

z

2

lim

]

[

y 1

1

1

z

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-17-2048.jpg)

![19

Power Series Method

Example 2: Determine the z-transform of

2

1

z

5

.

0

z

5

.

1

1

1

)

z

(

X

By dividing the numerator of X(z) by its

denominator, we obtain the power series

...

z

z

z

z

1

z

z

1

1 4

16

31

3

8

15

2

4

7

1

2

3

2

2

1

1

2

3

x[n] = [1, 3/2, 7/2, 15/8, 31/16,…. ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-19-2048.jpg)

![20

Power Series Method

Example 2:Determine the z-transform of

2

1

1

z

z

2

2

z

4

)

z

(

X

By dividing the numerator of X(z) by its

denominator, we obtain the power series

x[n] = [2, 1.5, 0.5, 0.25, …..]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-20-2048.jpg)

![21

Partial Fraction Method:

Example 1: Find the signal corresponding to

the z-transform

2

1

3

z

z

3

2

z

)

z

(

X

Solution:

5

.

0

z

1

z

z

5

.

0

z

5

.

0

z

5

.

1

z

5

.

0

z

z

3

2

z

)

z

(

X 2

3

2

1

3

5

.

0

z

4

1

z

1

z

1

z

3

5

.

0

z

1

z

z

5

.

0

z

)

z

(

X

2

2

5

.

0

z

z

)

4

(

1

z

z

z

1

3

)

z

(

X

or 1

1

1

z

5

.

0

1

1

4

z

1

1

z

3

)

z

(

X

]

n

[

u

5

.

0

4

]

n

[

u

]

1

n

[

]

n

[

3

]

n

[

x

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-21-2048.jpg)

![22

Partial Fraction Method:

Example 2: Find the signal corresponding to the z-

transform

2

1

1

z

2

.

0

1

z

2

.

0

1

1

)

z

(

Y

Solution:

2

3

2

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

z

)

z

(

Y

2

2

2

2

.

0

z

1

.

0

2

.

0

z

75

.

0

2

.

0

z

25

.

0

2

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

z

z

)

z

(

Y

2

2

.

0

z

z

1

.

0

2

.

0

z

z

75

.

0

1

z

z

25

.

0

)

z

(

Y

2

1

1

2

.

0

1

.

0

1

1

z

2

.

0

1

z

2

.

0

z

2

.

0

1

1

75

.

0

z

2

.

0

1

1

25

.

0

]

n

[

u

2

.

0

n

5

.

0

]

n

[

u

2

.

0

75

.

0

]

n

[

u

2

.

0

25

.

0

]

n

[

y

n

n

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-22-2048.jpg)

![23

The One-Sided z-Transform

The one-sided or unilateral z-transform of a signal

x[n] is defined by

0

n

n

z

]

n

[

x

)

z

(

X

Characteristics:

•It does not contain information about the

signal x[n] for negative values of time.

• It is unique only for causal signals.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-23-2048.jpg)

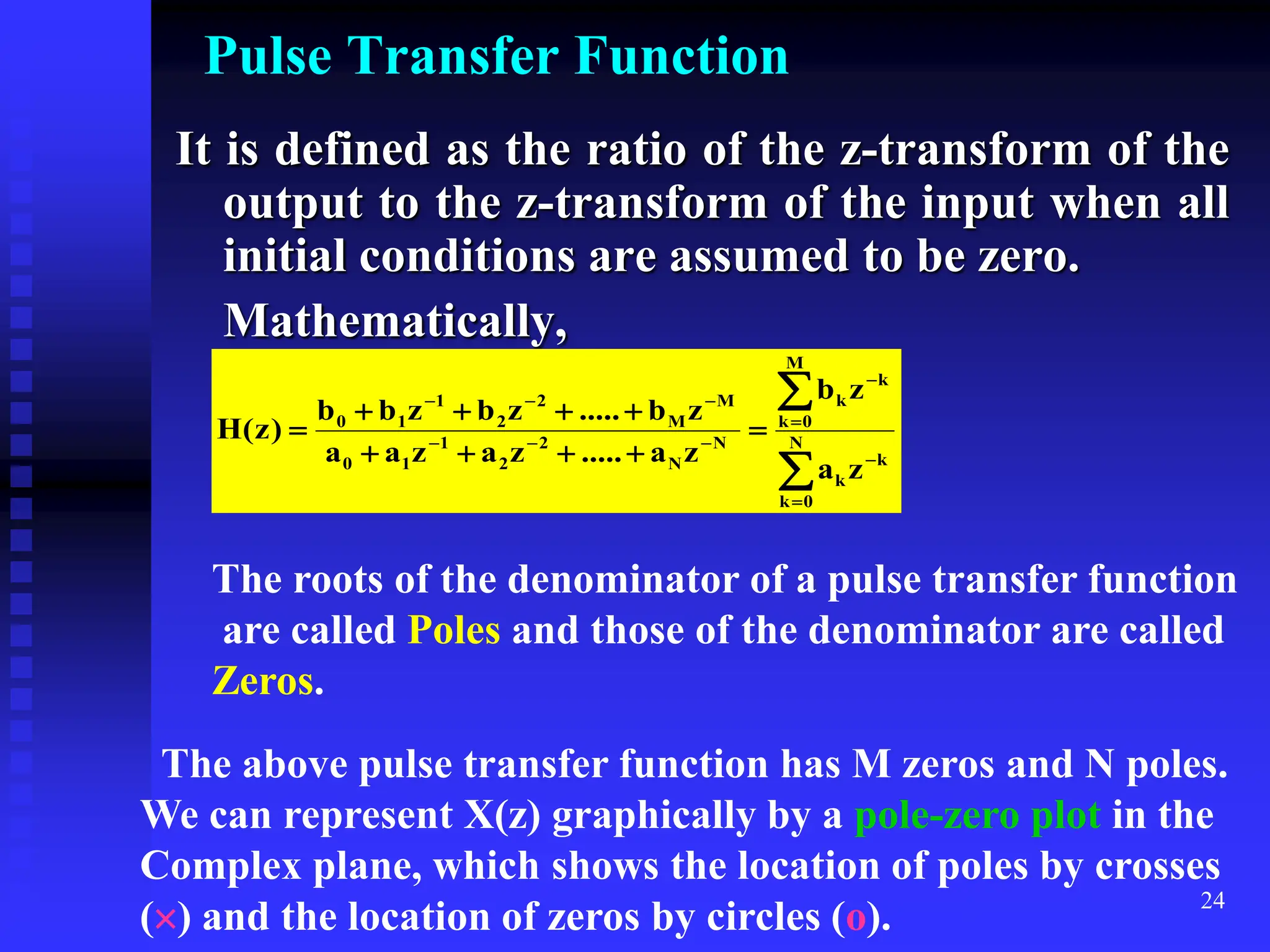

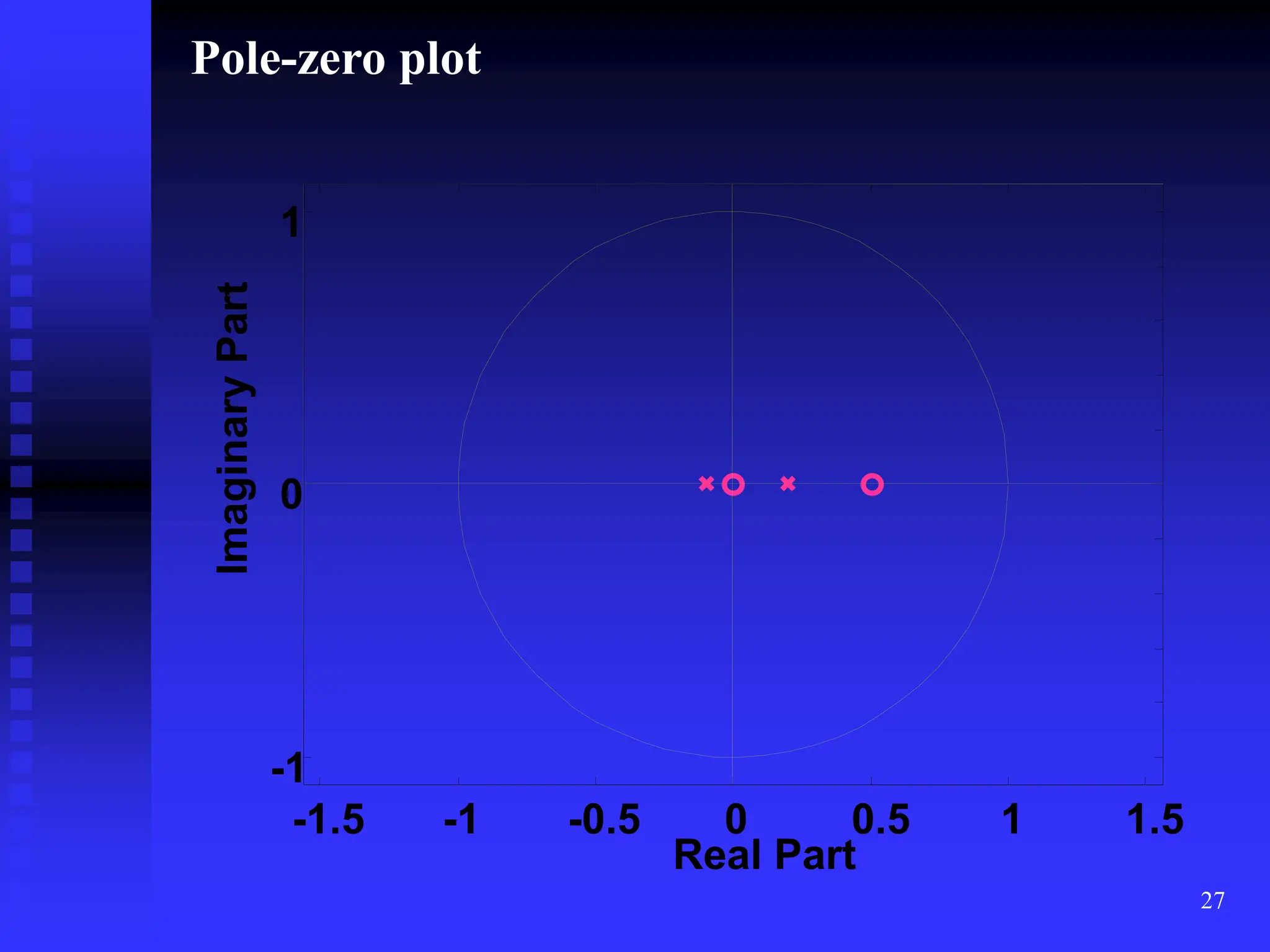

![26

Example: A system is characterized by

by the difference equation

y[n] – 0.1y[n-1] – 0.02 y[n-2] = 2x[n] – x[n-1].

Find the system transfer function and unit

impulse response.

Solution: Taking the z-transform of both sides of the

difference equation (ignoring the initial

conditions) we have

Y(z) – 0.1 z-1Y(z) – 0.02z-2Y(z) = 2X(z) – z-1X(z)

Y(z) [ 1 –0.1z-1 – 0.02z-2 ]= X(z [2 – z-1]

2

1

1

z

02

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

2

)

z

(

X

)

z

(

Y

This transfer function has two poles (i.e. z = -0.1, 0.2) and

Two zeros at z =0, 0.5. This shows that the system is

BIBO stable. The Pole-zero plot is given on the next slide.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-26-2048.jpg)

![28

To find the unit impulse response, we

compute the inverse z-transform of H(z) by

using partial fraction expansion:

1

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

2

z

2

02

.

0

z

1

.

0

z

z

z

2

z

02

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

2

)

z

(

H

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

.

0

z

4

2

.

0

z

2

1

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

1

z

2

z

)

z

(

H

1

1

z

1

.

0

1

1

4

z

2

.

0

1

1

2

1

.

0

z

z

4

2

.

0

z

z

2

)

z

(

H

and, the unit impulse response is

H[n] = -2(0.2)nu[n] + 4(-0.1)nu[n]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-28-2048.jpg)

![29

Response of systems with non-zero initial

conditions

We can use z-transform to solve the difference

equation that characterizes a causal, linear, time

invariant system. The following expressions are

especially useful to solve the difference

equations:

z[y[(n-1)T] = z-1Y(z) +y[-T]

Z[y(n-2)T] = z-2Y(z) + z-1y[-T] + y[-2T]

Z[y(n-3)T] = z-3Y(z) + z-2y[-T] + z-1y[-2T] +

y[-3T]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-29-2048.jpg)

![30

Tutorial 5 Q1: Determine the step response of

the system

y[n]=ay[n-1] + x[n], -1 < a < 1

when the initial condition is y[-1] = 1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-30-2048.jpg)

![31

Example: Consider the following difference

equation:

y[nT] –0.1y[(n-1)T] – 0.02y[(n-2)T] = 2x[nT] –

x[(n-1)T]

where the initial conditions are y[-T] = -10 and y[-

2T] = 20. Find the output y[nT] when x[nT] is the

unit step input.

Solution:

Computing the z-transform of the difference

equation gives

Y(z) – 0.1[z-1Y(z) + y[-T]] – 0.02[z-2Y(z) + z-1y[-T]

+ y[-2T]] = 2X(z) – z-1X(z)

Substituting the initial conditions we get

Y(z) – 0.1z-1Y(z) +1 – 0.02z-2Y(z) + 0.2z-1 –0.4 =

(2 – z-1)X(z)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-31-2048.jpg)

![32

6

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

1

1

z

2

)

z

(

Y

z

02

.

0

z

1

.

0

1 1

1

1

2

1

6

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

1

z

2

z

02

.

0

z

2

.

0

1

)

z

(

Y 1

1

1

2

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

2

1

z

1

.

0

1

z

2

.

0

1

z

1

z

2

.

0

z

6

.

0

4

.

1

z

02

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

1

z

2

.

0

z

6

.

0

4

.

1

)

z

(

Y

1

.

0

z

2

.

0

z

1

z

z

2

.

0

z

6

.

0

z

4

.

1 2

3

1

.

0

z

830

.

0

2

.

0

z

567

.

0

1

z

136

.

1

z

)

z

(

Y

1

1

1

z

1

.

0

1

1

830

.

0

z

2

.

0

1

1

567

.

0

z

1

1

136

.

1

)

z

(

Y

and the output signal y[nT] is

]

nT

[

u

)

1

.

0

(

830

.

0

]

nT

[

u

)

2

.

0

(

567

.

0

]

nT

[

u

136

.

1

]

nT

[

y n

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-32-2048.jpg)

![34

Example: Determine the unit impulse response of

the system characterized by the difference

equation

y[n] = 2.5y[n-1] – y[n-2] + x[n] – 5x[n-1] + 6x[n-2]

Solution: Taking the z-transform of both sides of

the above difference equation and ignoring all

initial conditions, we obtain the following pulse

transfer function:

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

1

1

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

z

1

z

5

.

2

1

z

1

z

3

1

z

2

1

z

1

z

3

1

z

2

1

z

z

5

.

2

1

z

6

z

5

1

)

z

(

H

and therefore

]

1

n

[

u

5

.

2

]

n

[

]

n

[

h

1

n

2

1

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-34-2048.jpg)

![36

Example: Determine the frequency response

function H(w) and the magnitude |H(w)|dB for the

LTI system characterized by the difference

equation

y[n] = 1.8y[n-1] – 0.81y[n-2] + x[n] + 0.95x[n-1]

Solution: The pulse transfer function is

2

1

1

2

1

1

z

9

.

0

1

z

95

.

0

1

z

81

.

0

z

8

.

1

1

z

95

.

0

1

)

z

(

H

Now the frequency response function may be obtained as

2

jw

jw

e

9

.

0

1

e

95

.

0

1

w

H

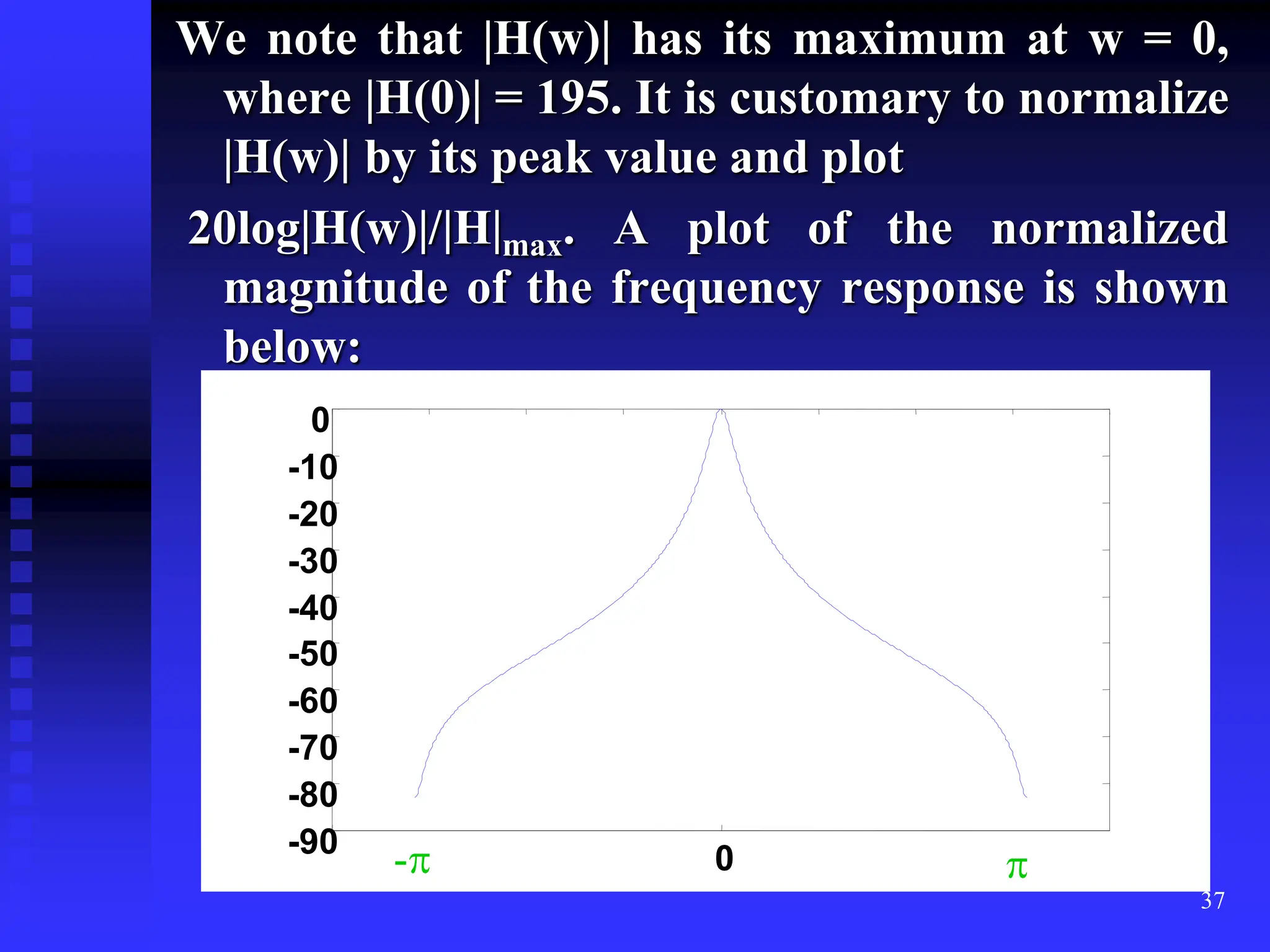

The magnitude response is

w

cos

8

.

1

81

.

1

w

cos

9

.

1

9025

.

1

|

)

w

(

H

|

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-36-2048.jpg)

![38

Example: Find the frequency response for the

system

y[n] = -0.1y[n-1] + 0.2y[n-2] + x[n] + x[n-1]

Solution: The system function is

2

1

1

z

2

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

1

)

z

(

H

Now

)

z

z

(

2

.

0

)

z

z

(

08

.

0

05

.

1

z

z

2

z

2

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

1

z

2

.

0

z

1

.

0

1

z

1

)

z

(

H

)

z

(

H 2

2

1

1

2

2

1

1

1

w

cos

8

.

0

w

cos

16

.

0

45

.

1

w

cos

2

2

|

)

z

(

H

)

z

(

H

|

|

)

w

(

H

| 2

e

z

1

2

jw

w

cos

8

.

0

w

cos

16

.

0

45

.

1

w

cos

2

2

|

)

w

(

H

| 2

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecz-transform-240123171651-ec7c8102/75/Z-transform-and-Properties-of-Z-Transform-38-2048.jpg)