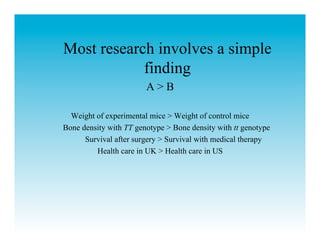

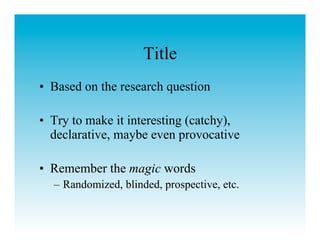

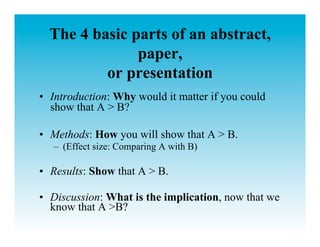

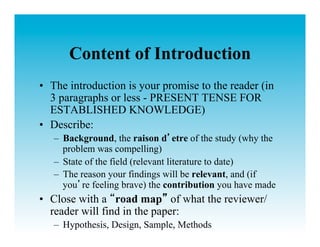

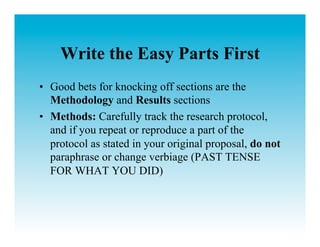

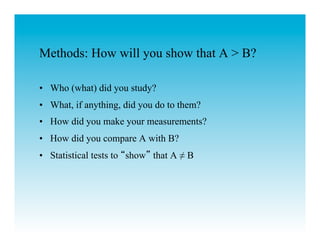

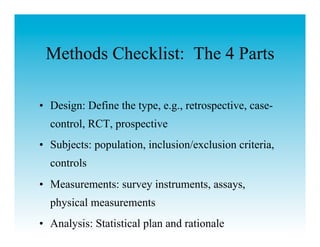

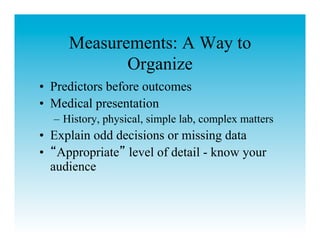

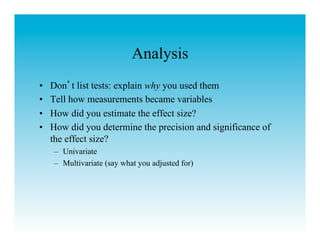

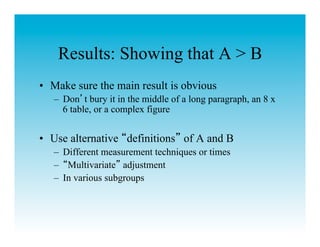

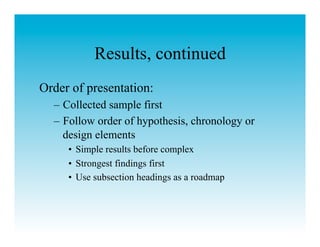

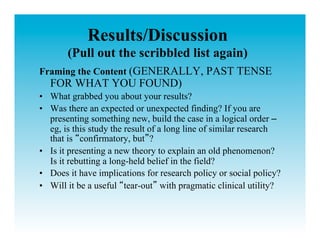

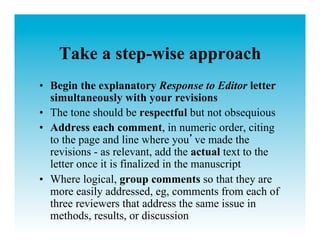

This document provides an overview and outline for a presentation on writing research papers and managing reviews. It discusses frameworks for timely presentation of research and reviews, including the Writer's Algorithm which outlines good writing habits and the typical sections of a paper. The presentation style is meant to be interactive, encouraging attendees to interrupt and share. Key aspects that will be covered include determining the audience and journals, writing the title, abstract, introduction and conclusion, and organizing the methods, results and discussion sections. Guidance is provided on writing each section and ensuring a logical flow that clearly presents the findings and their implications.