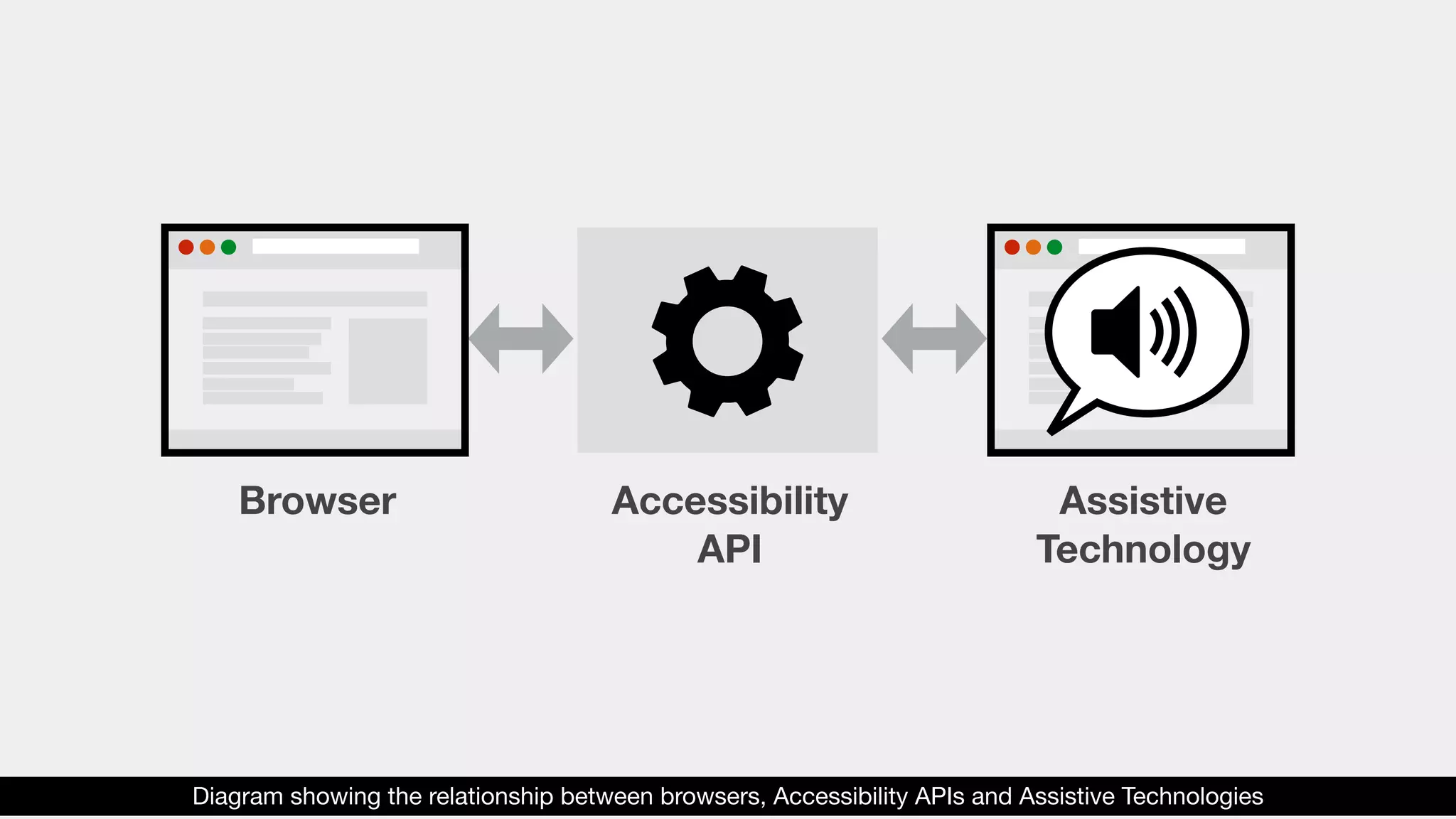

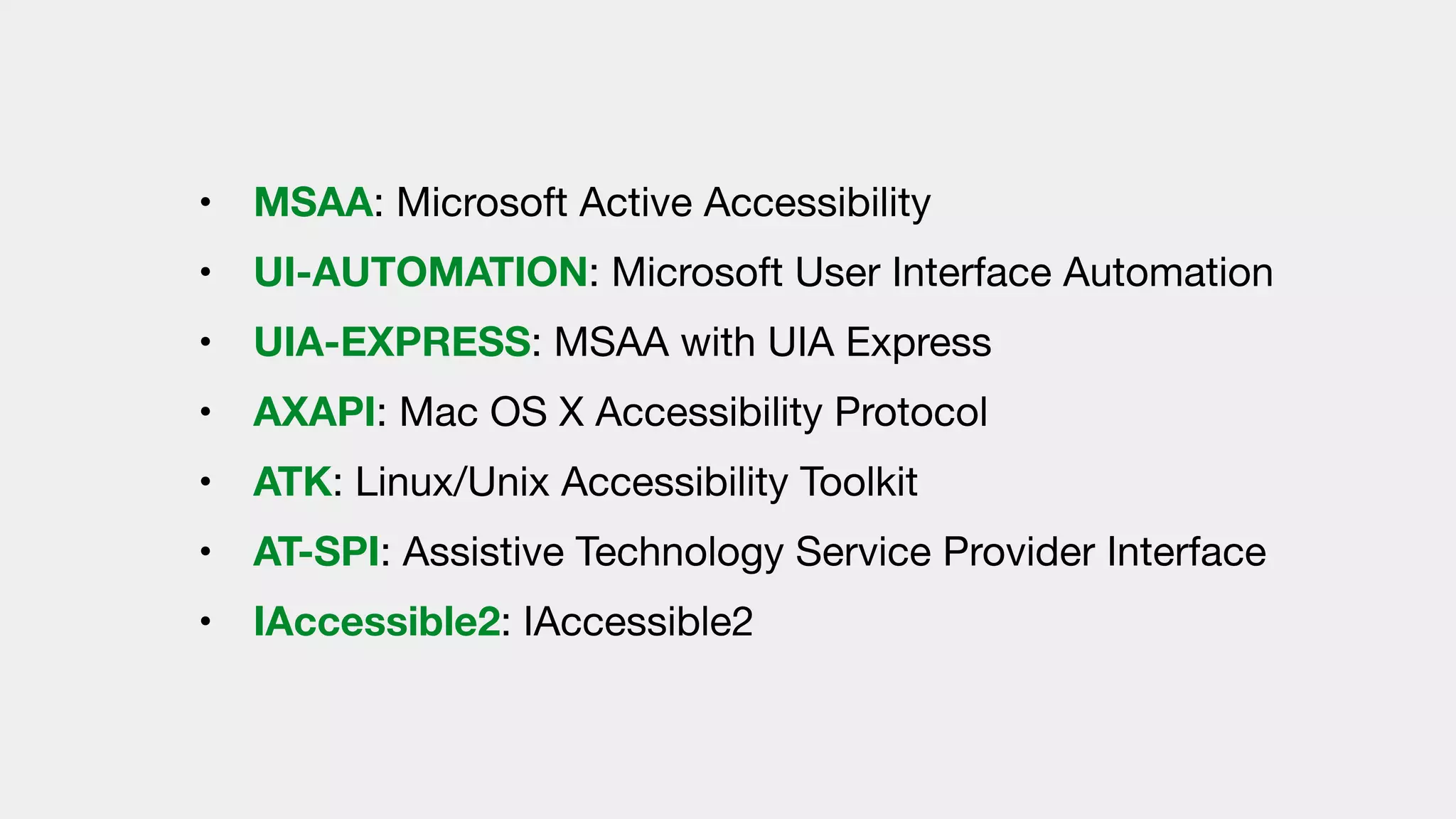

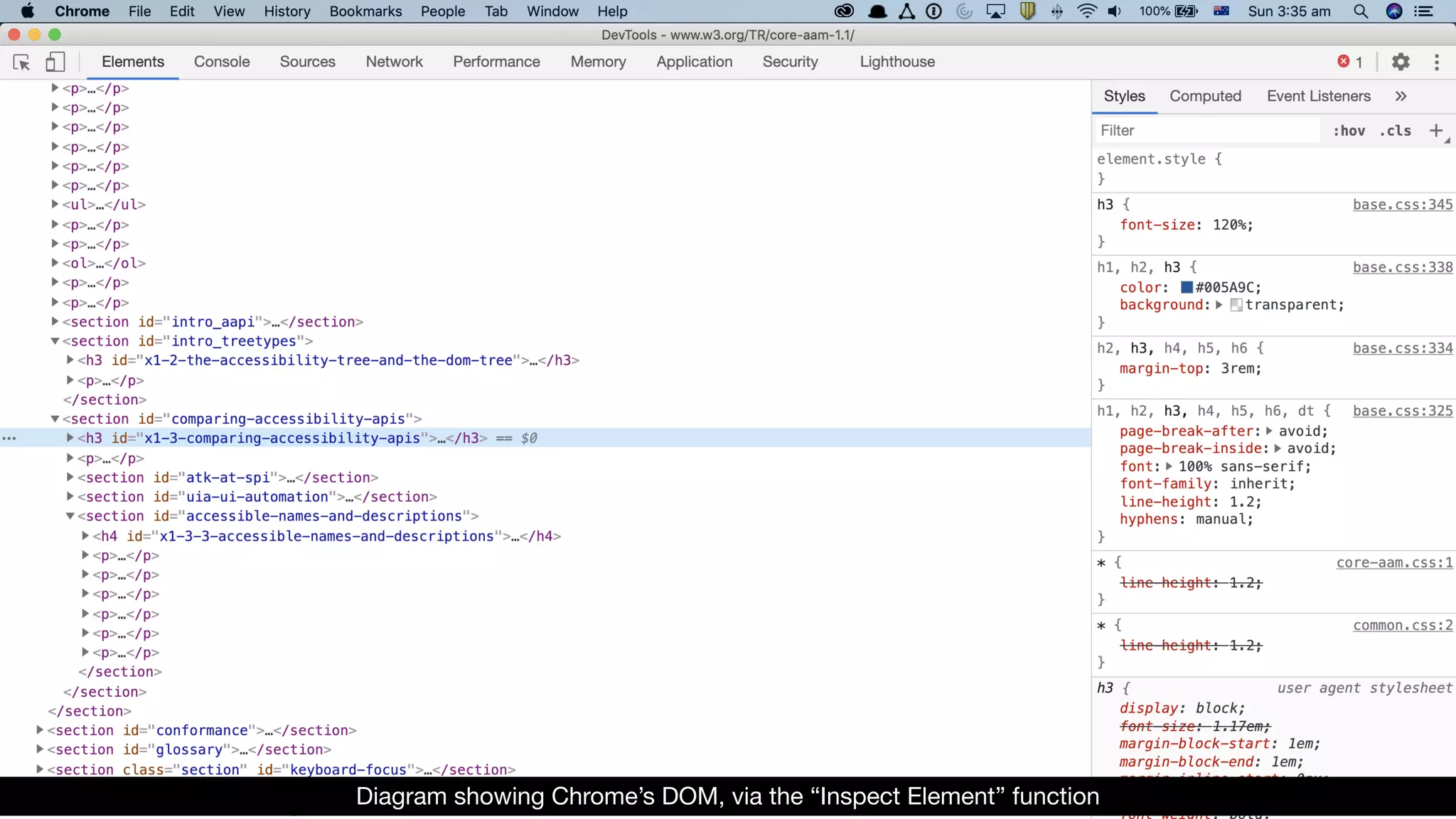

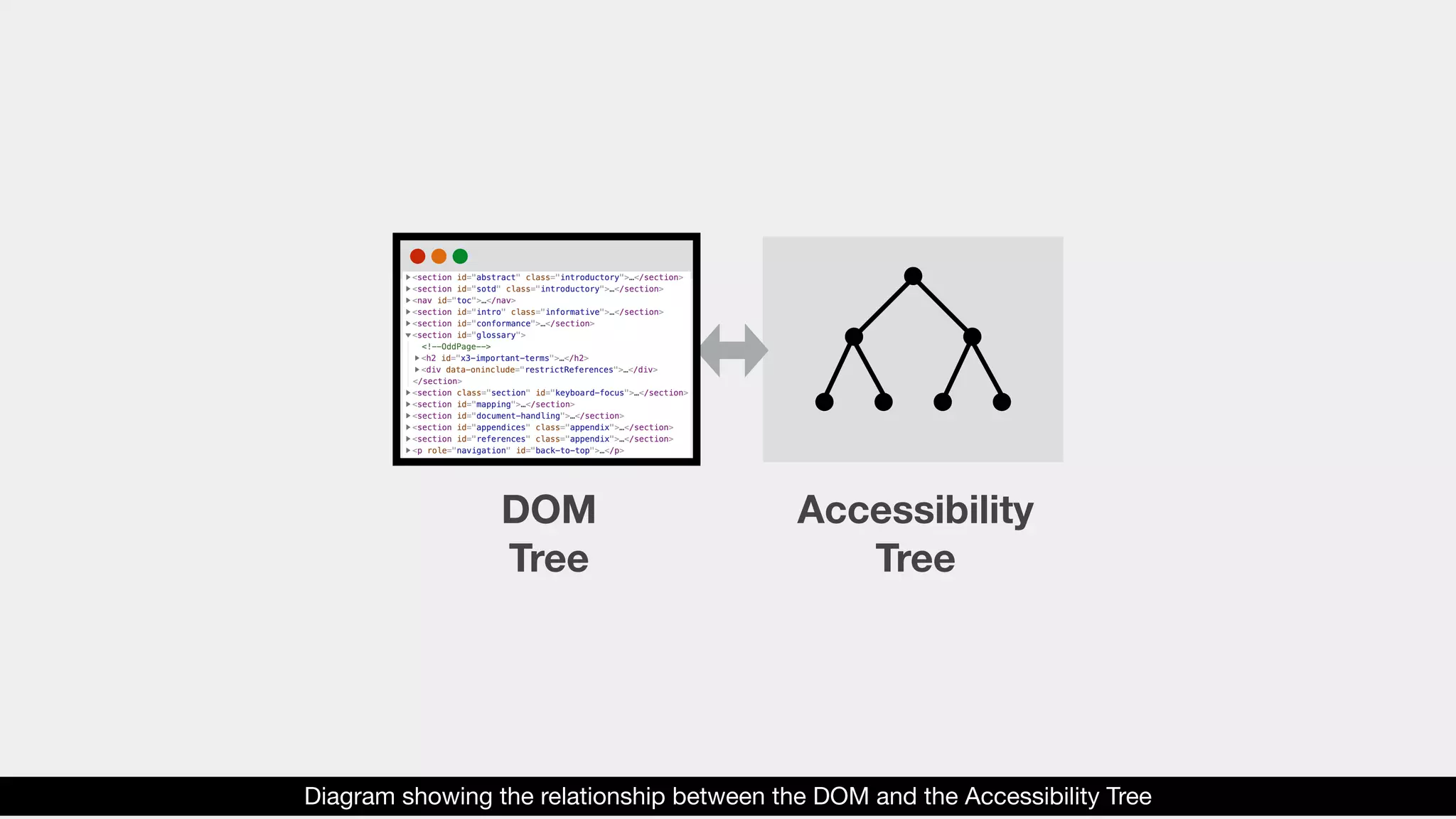

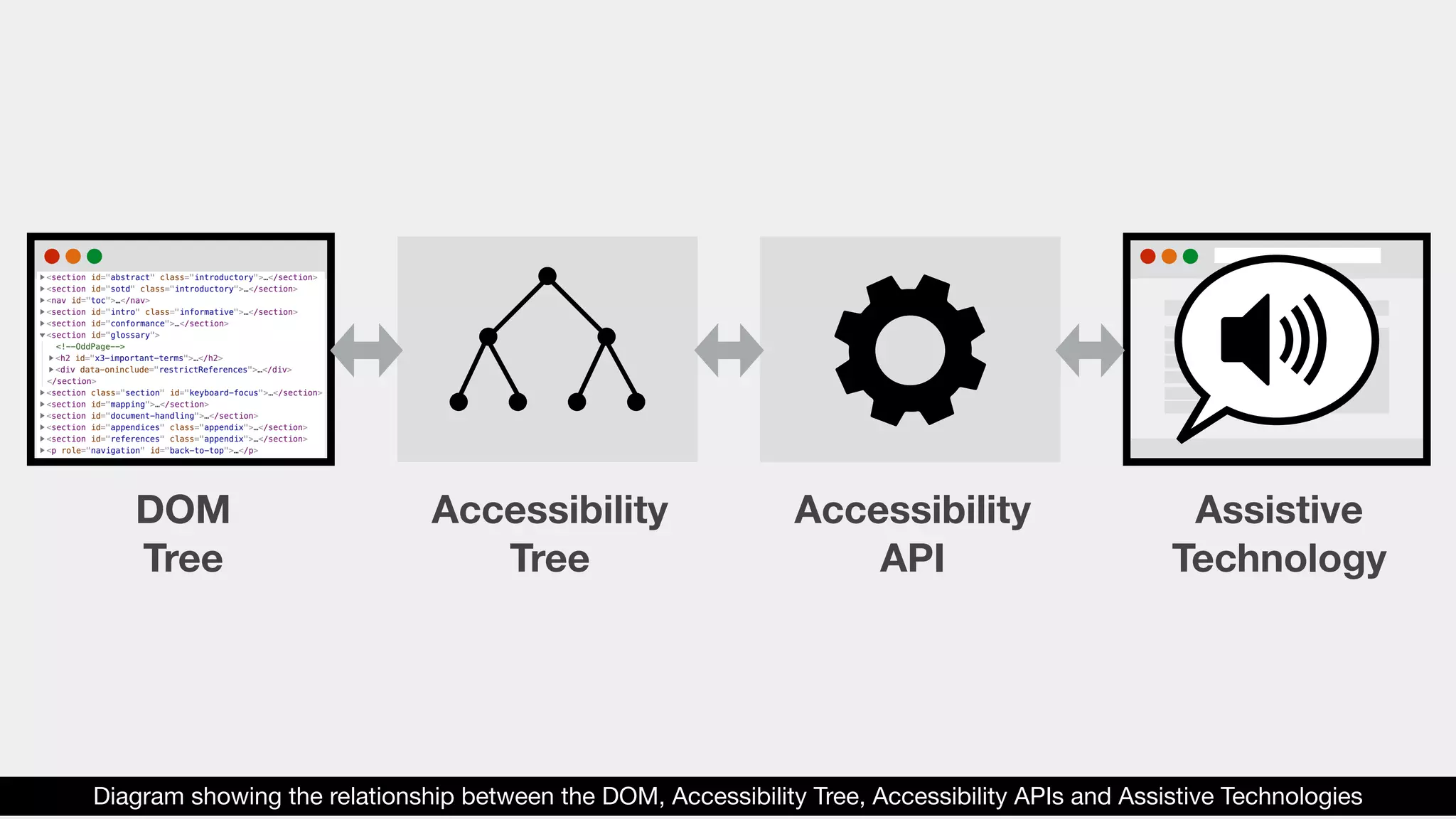

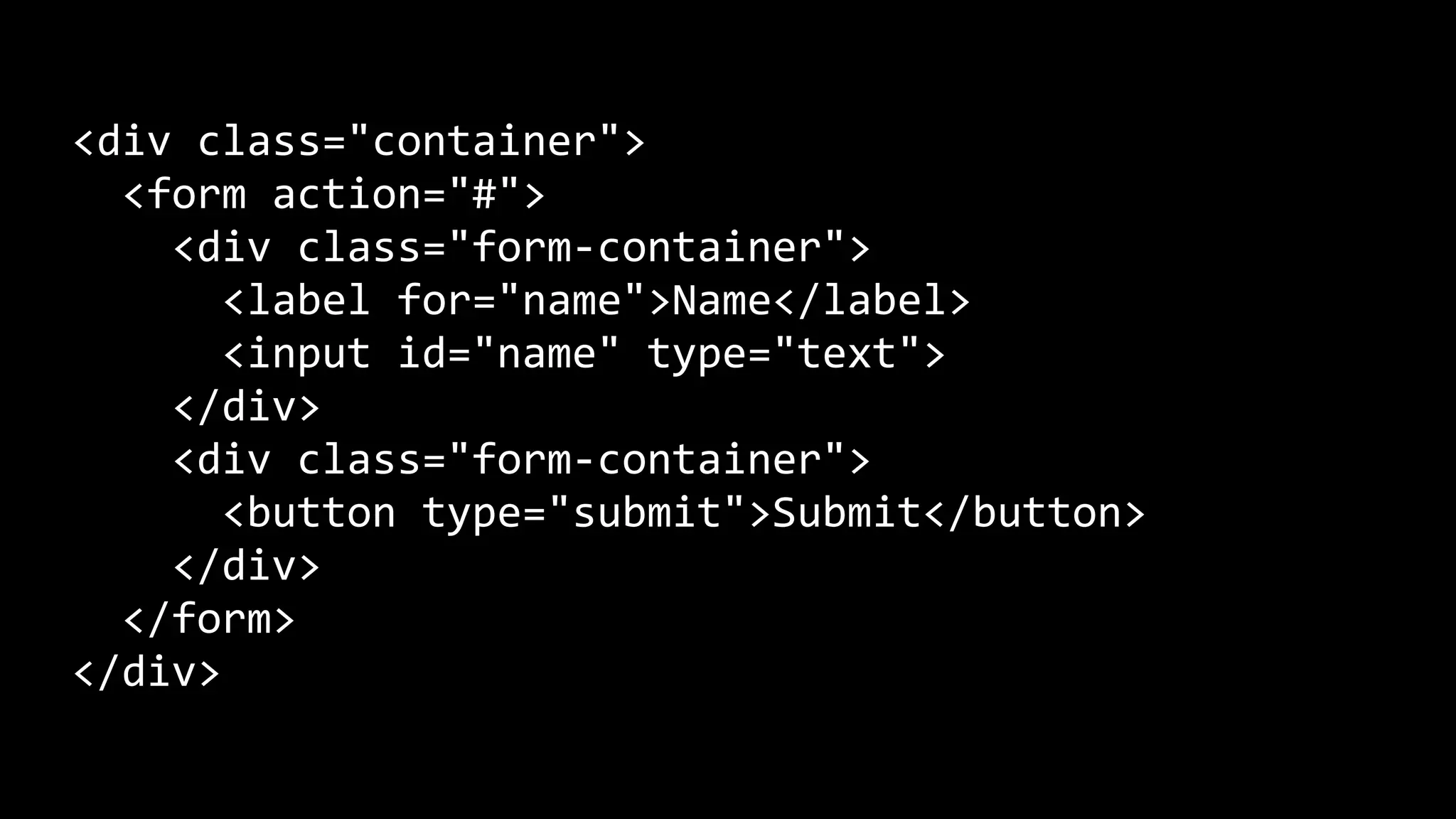

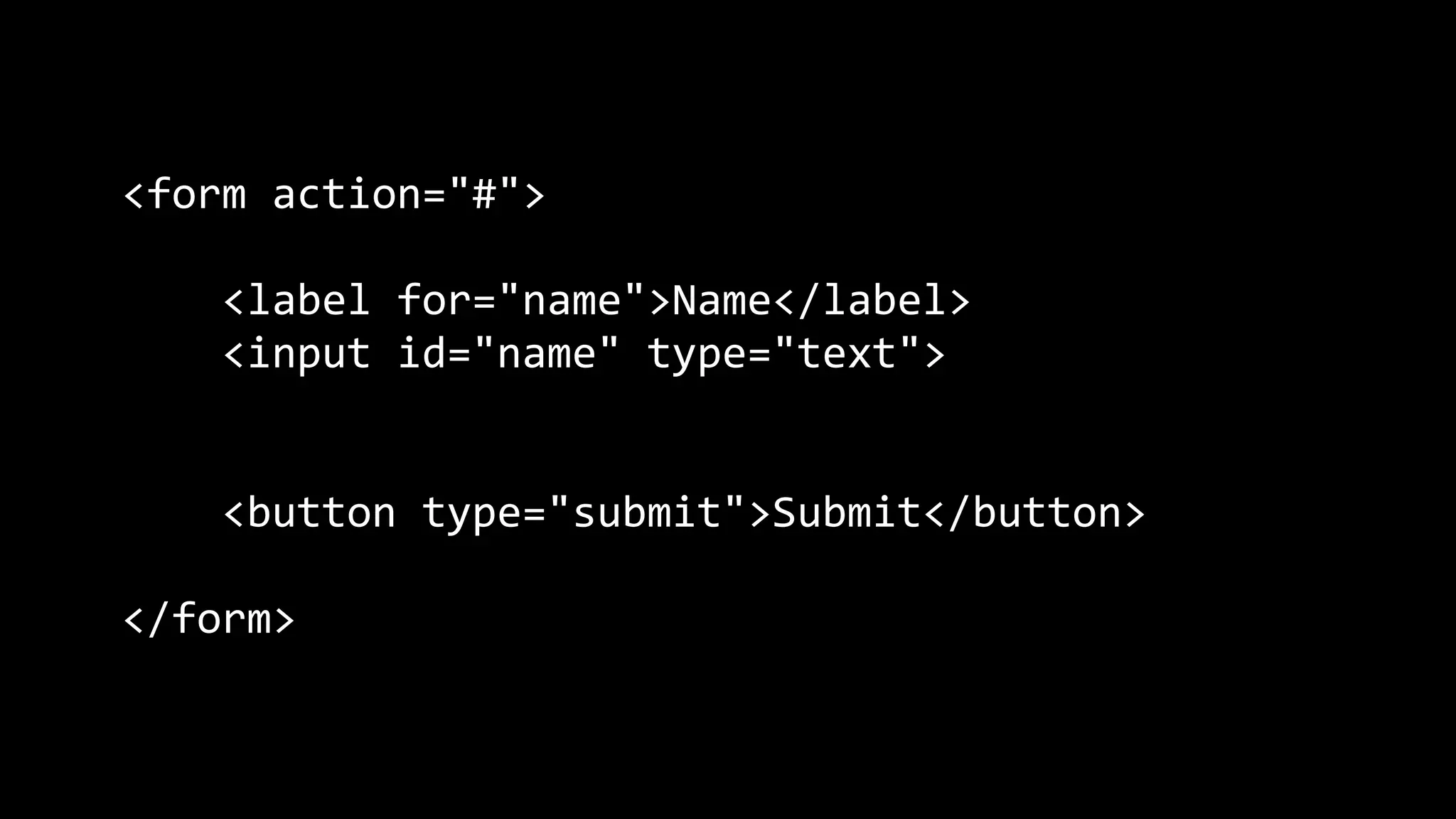

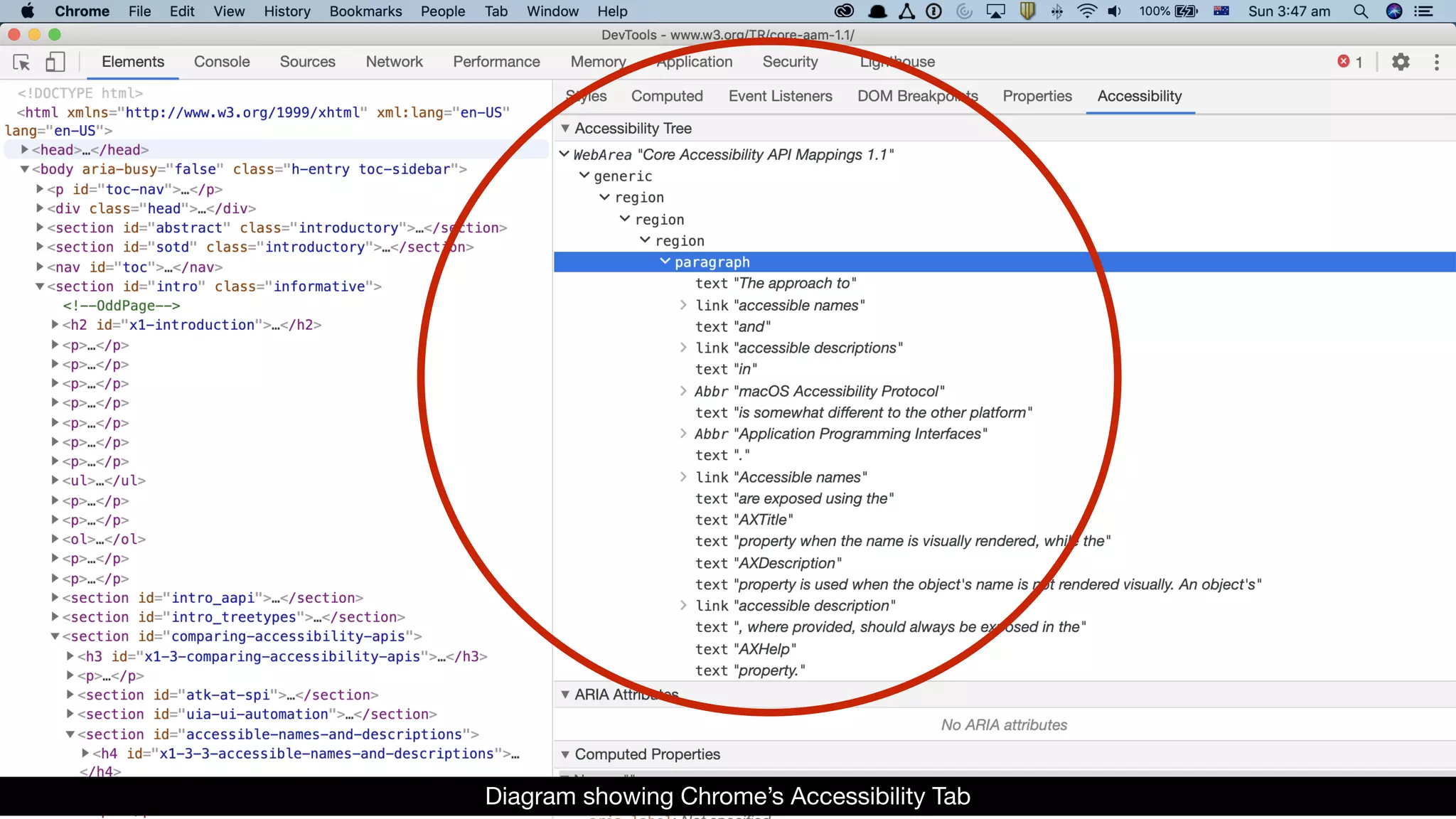

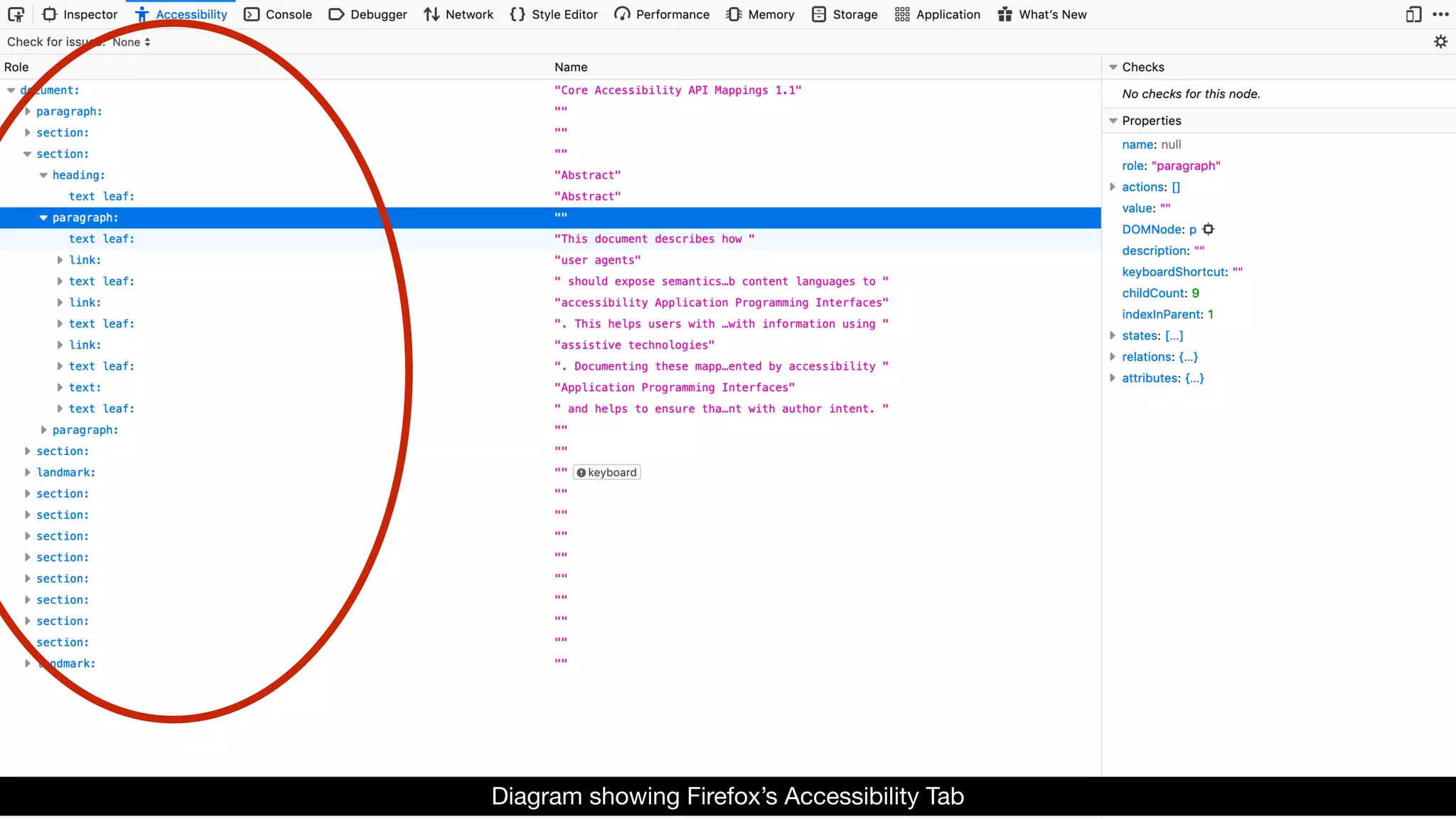

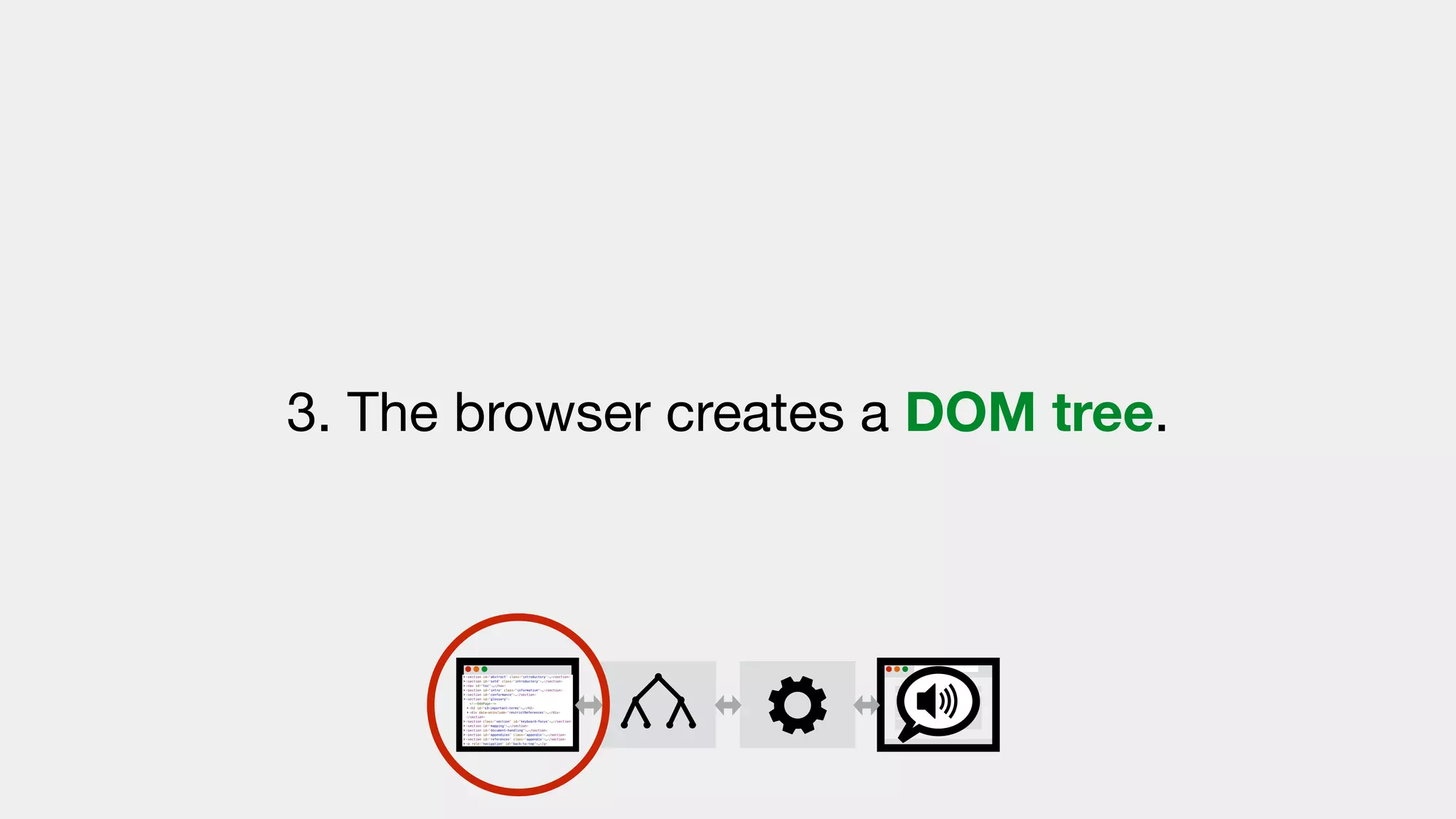

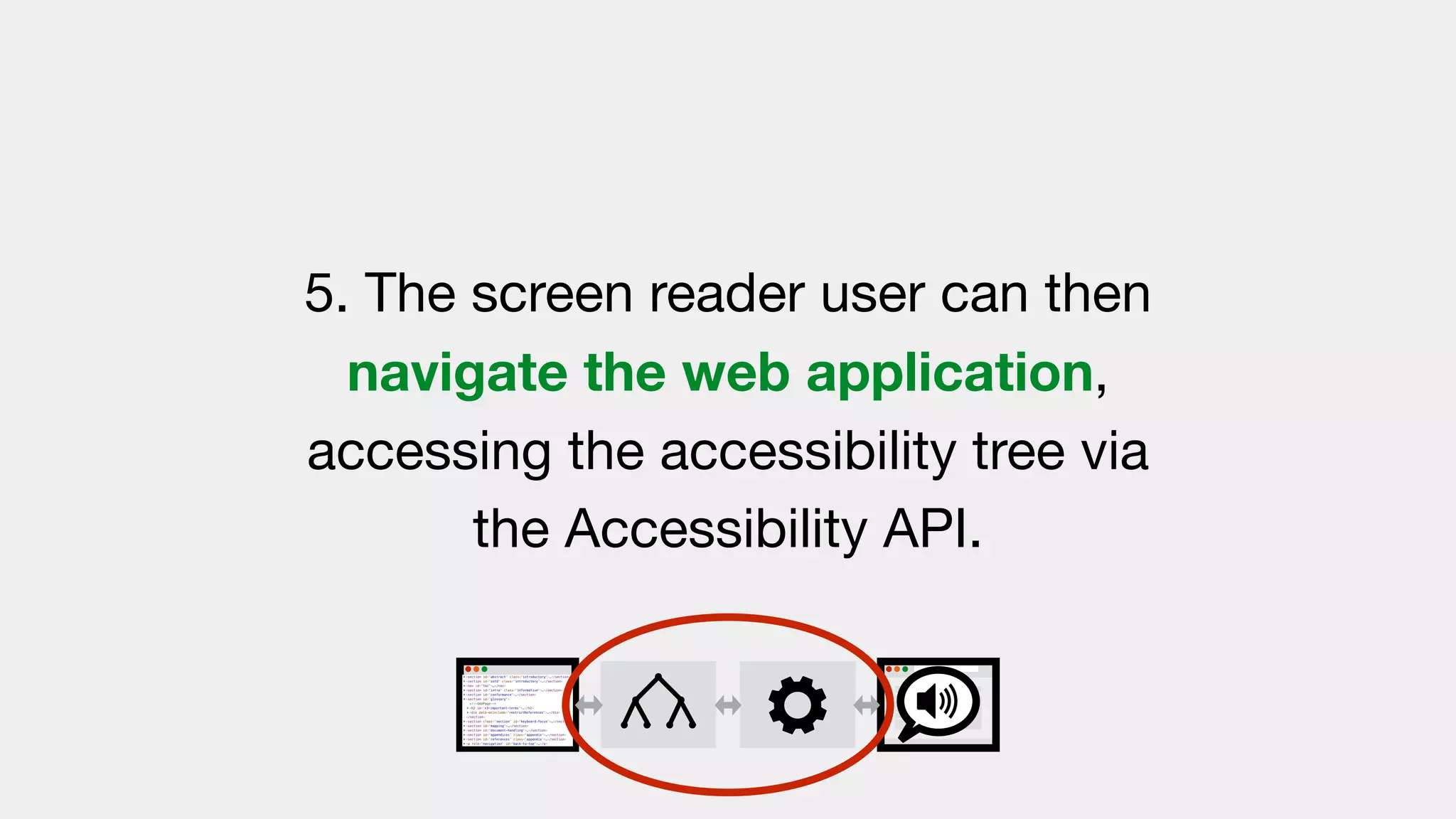

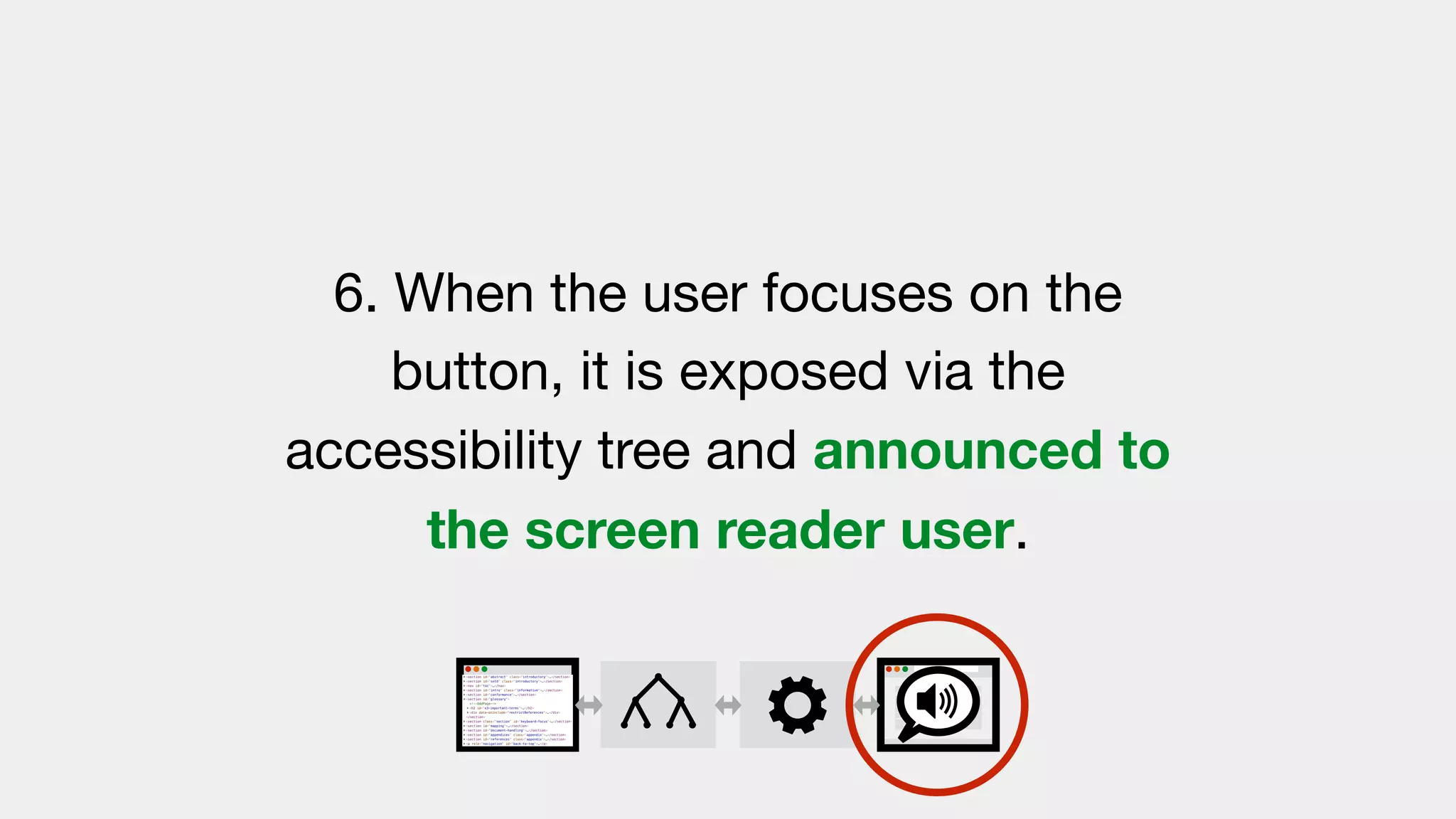

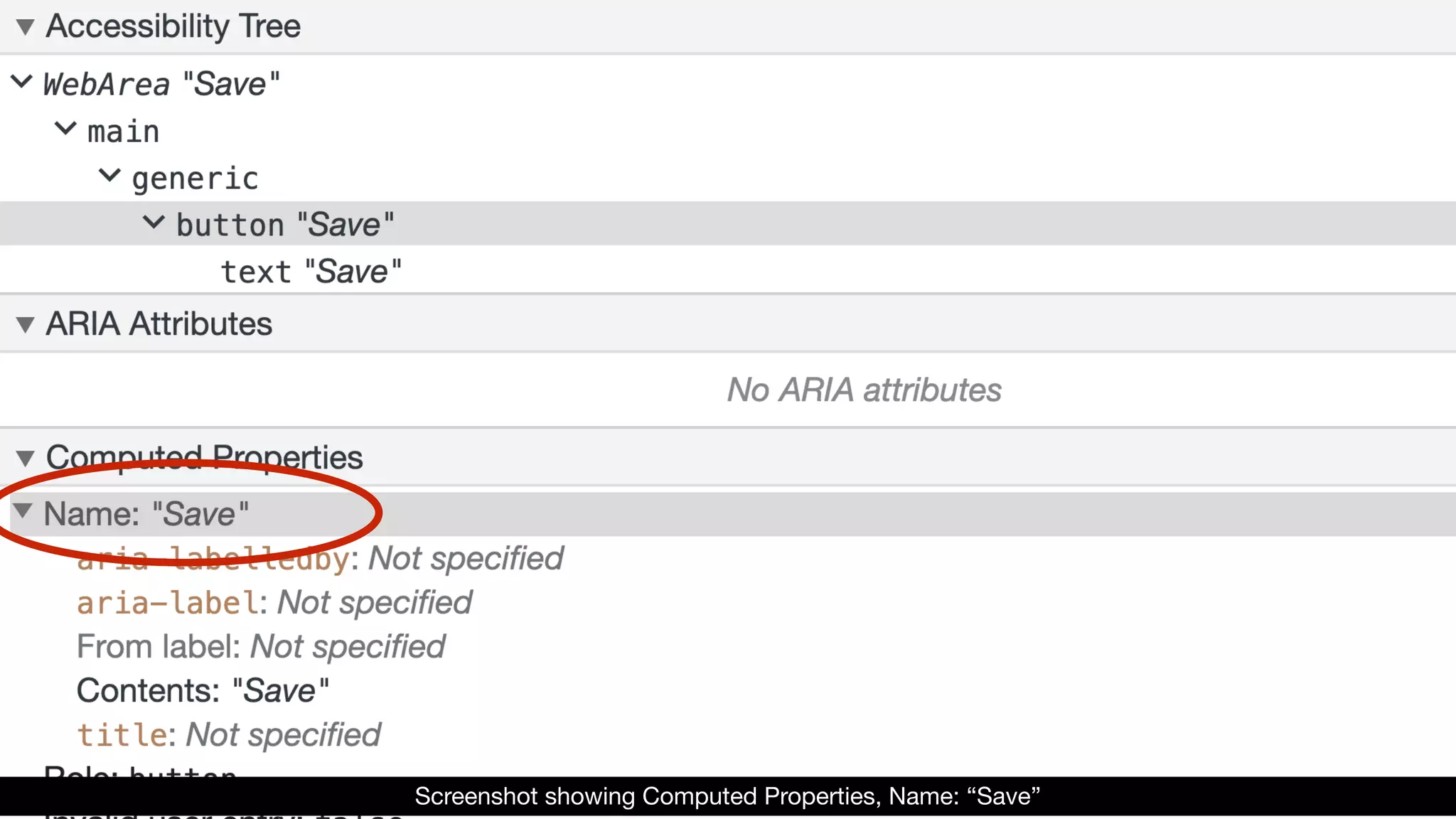

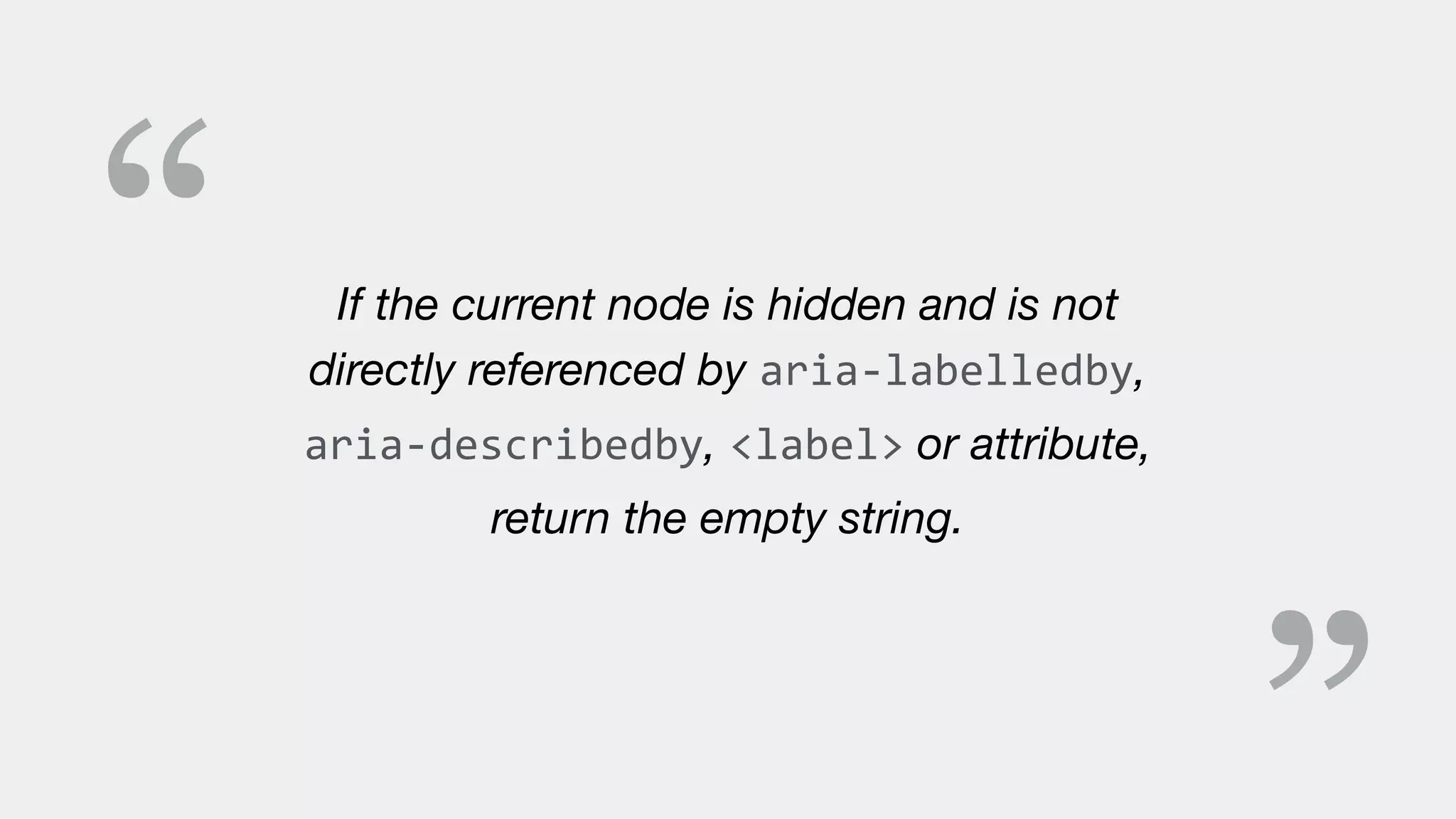

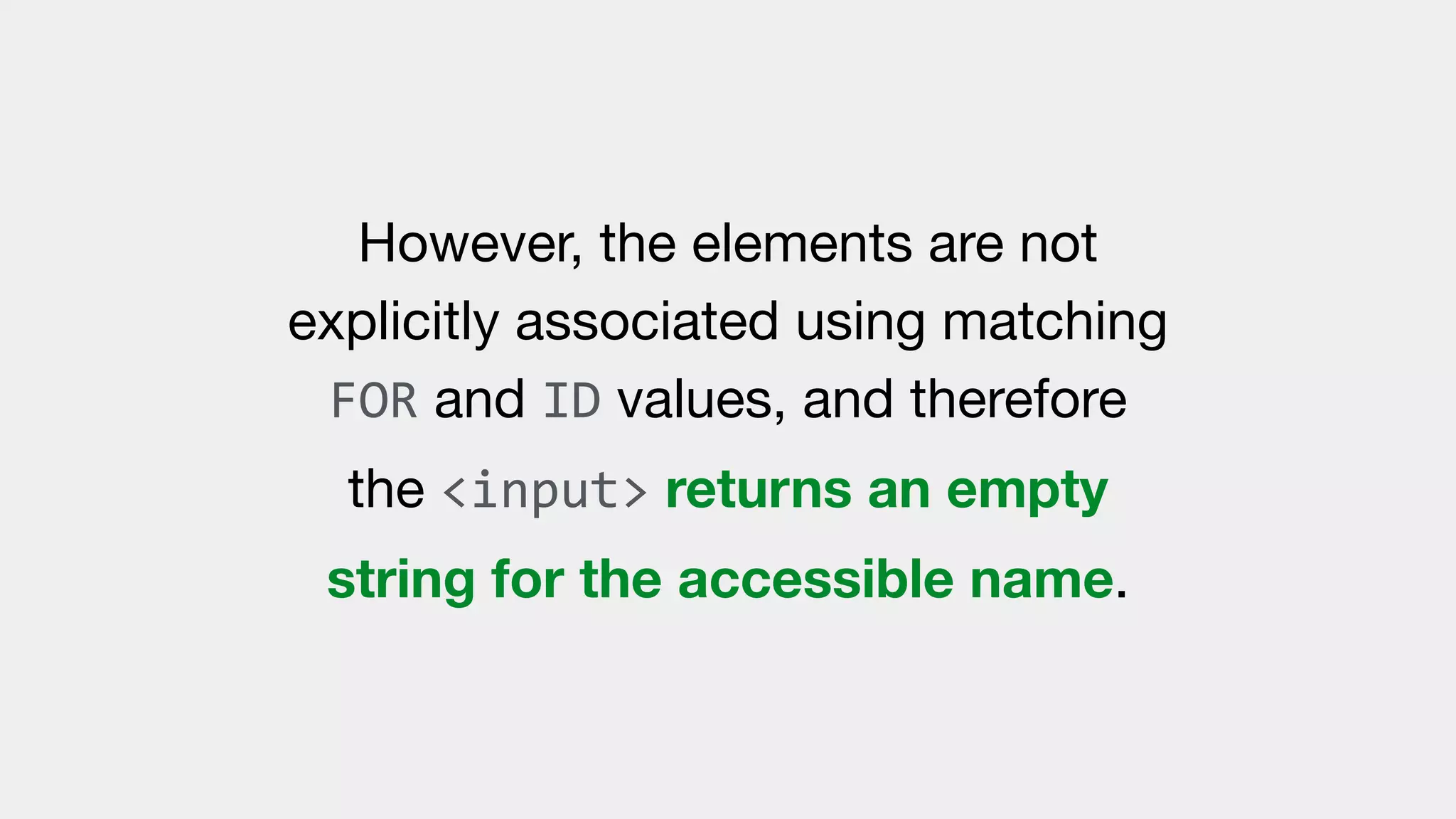

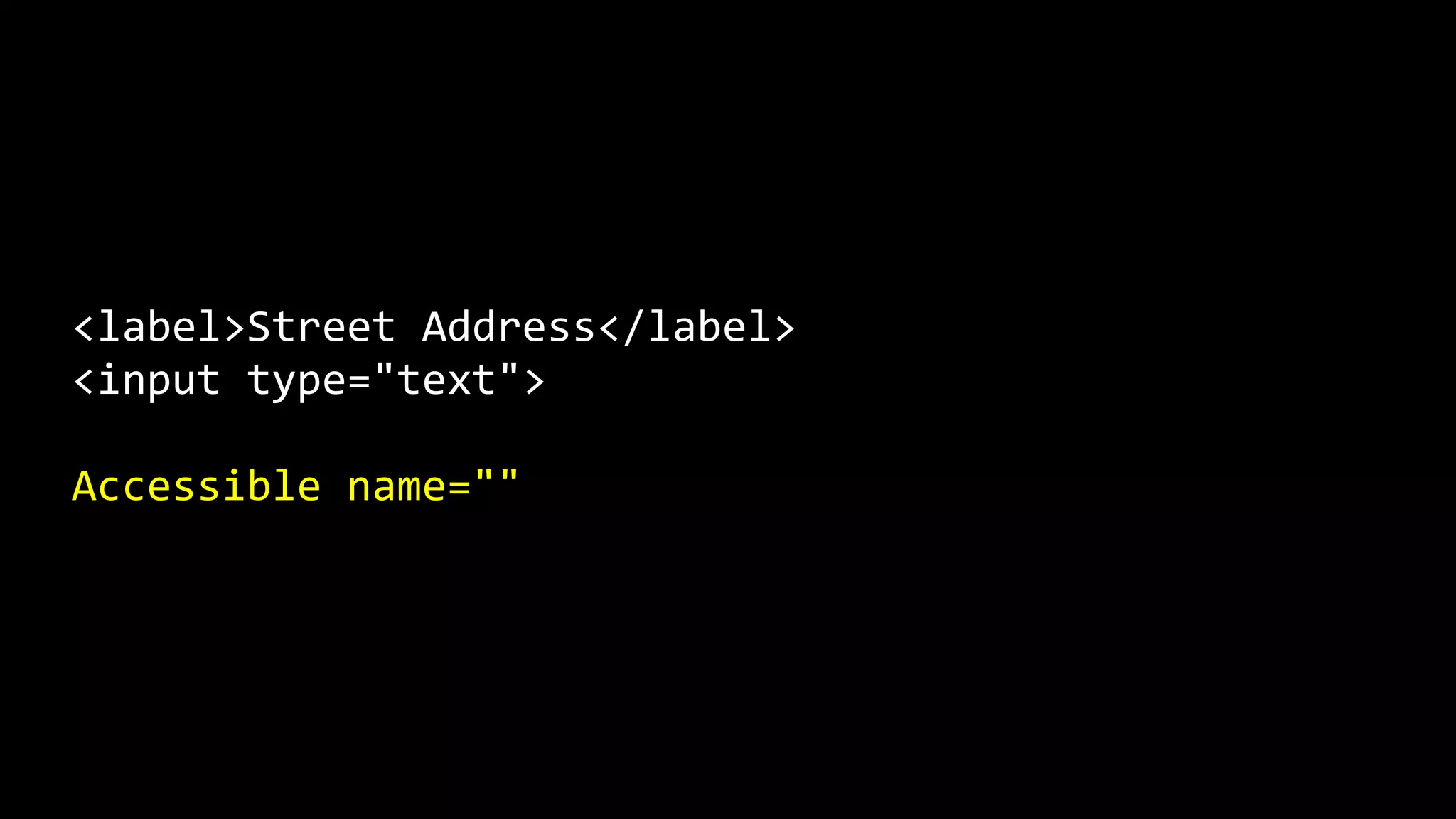

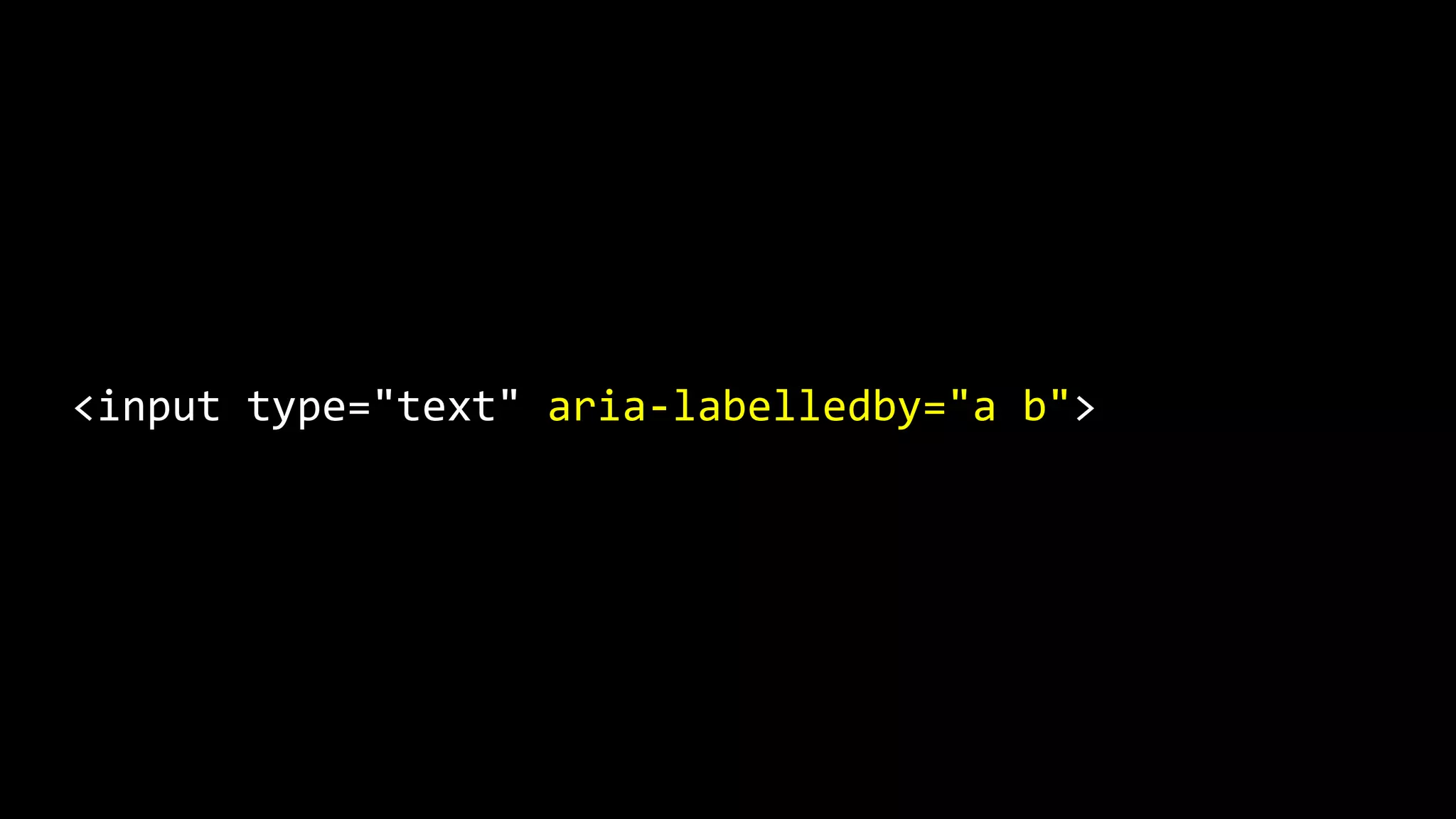

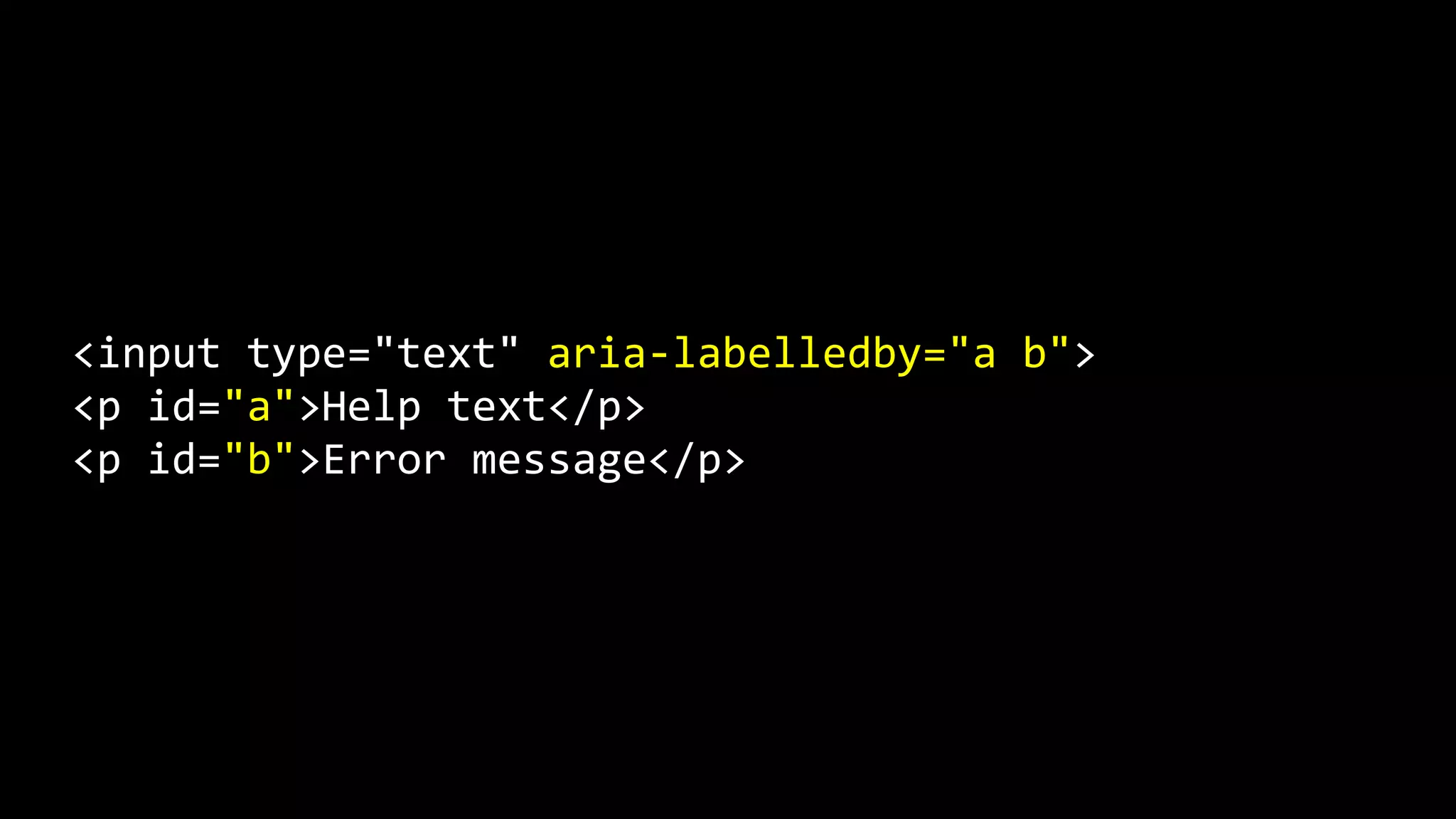

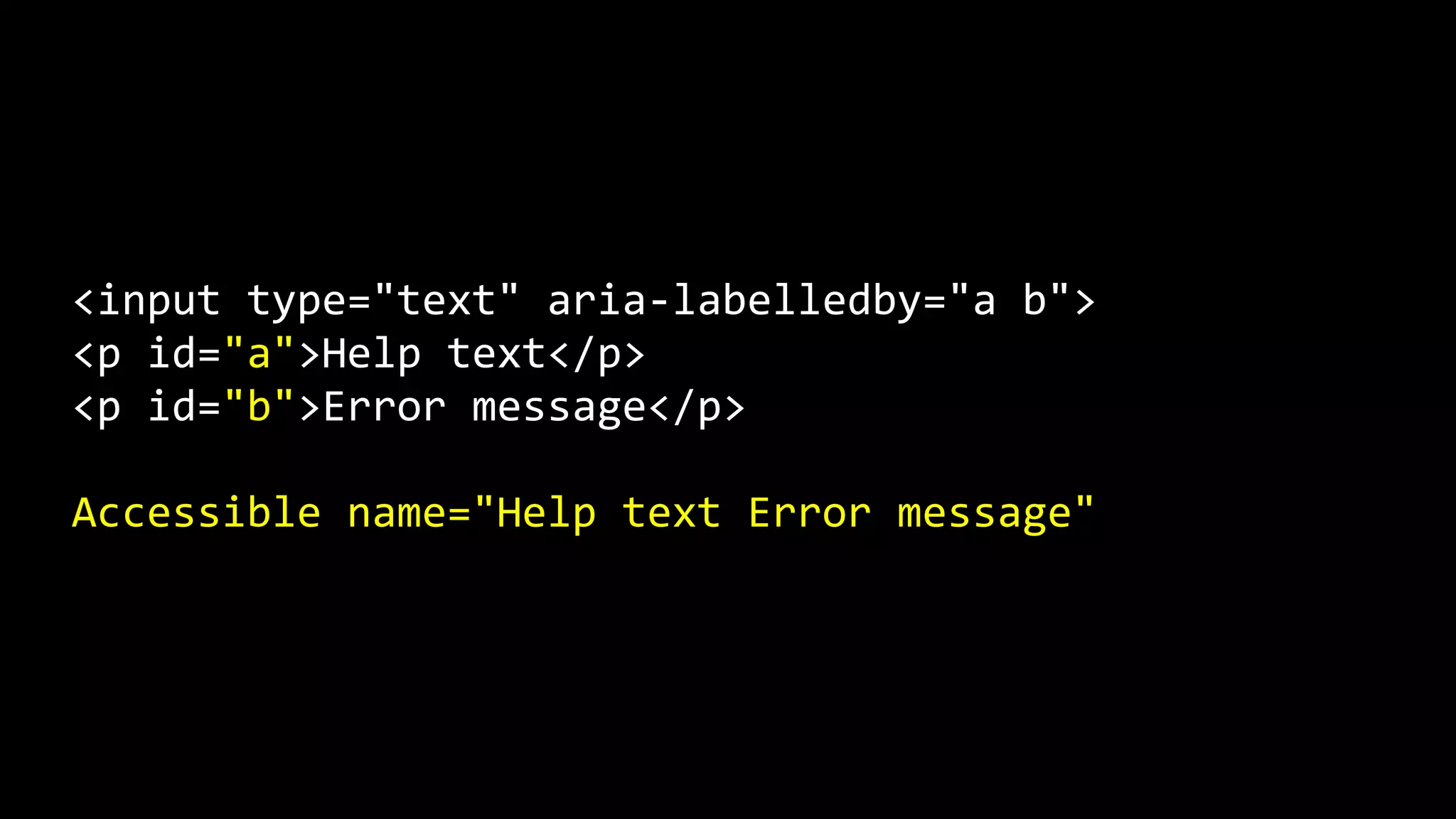

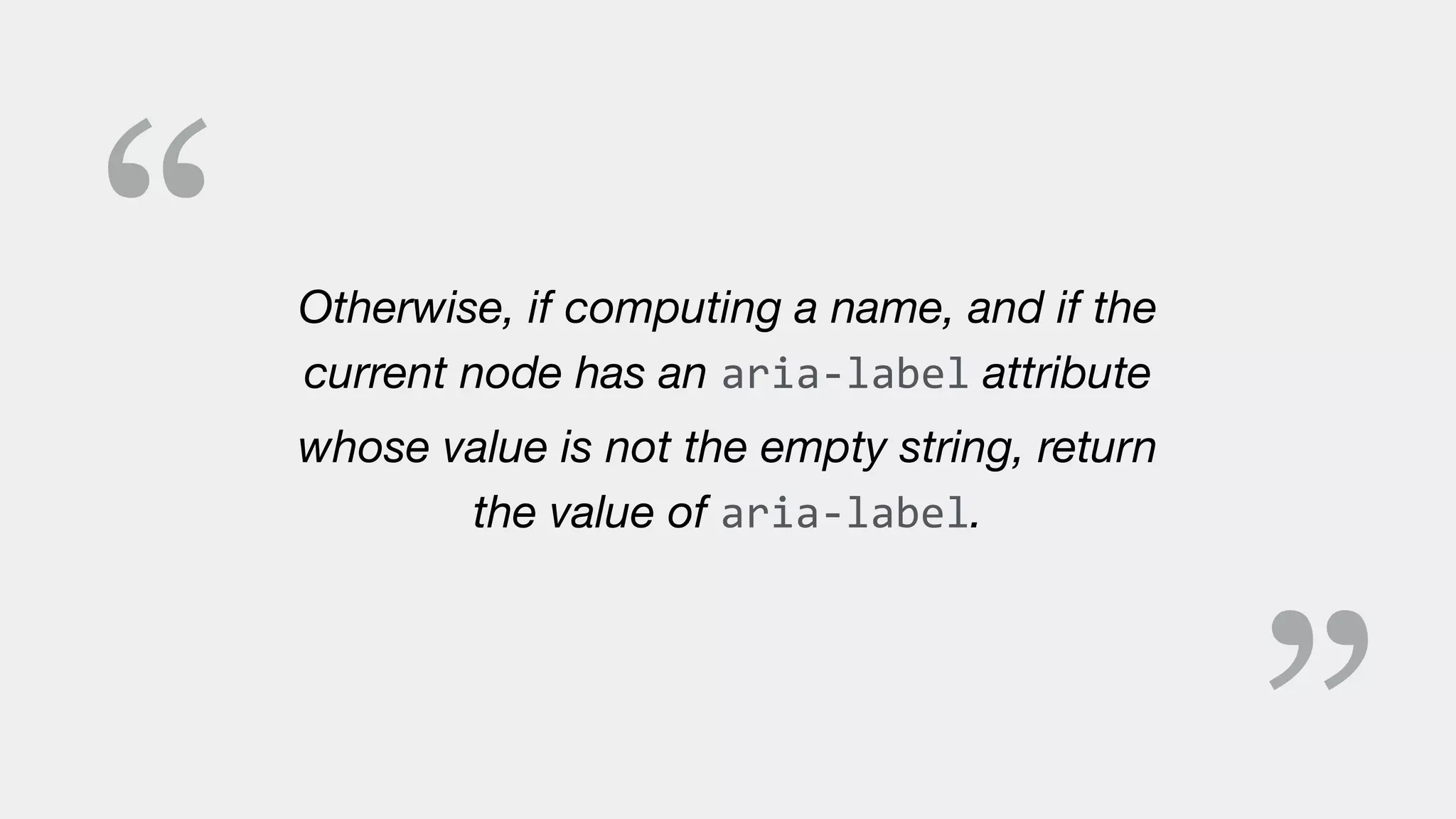

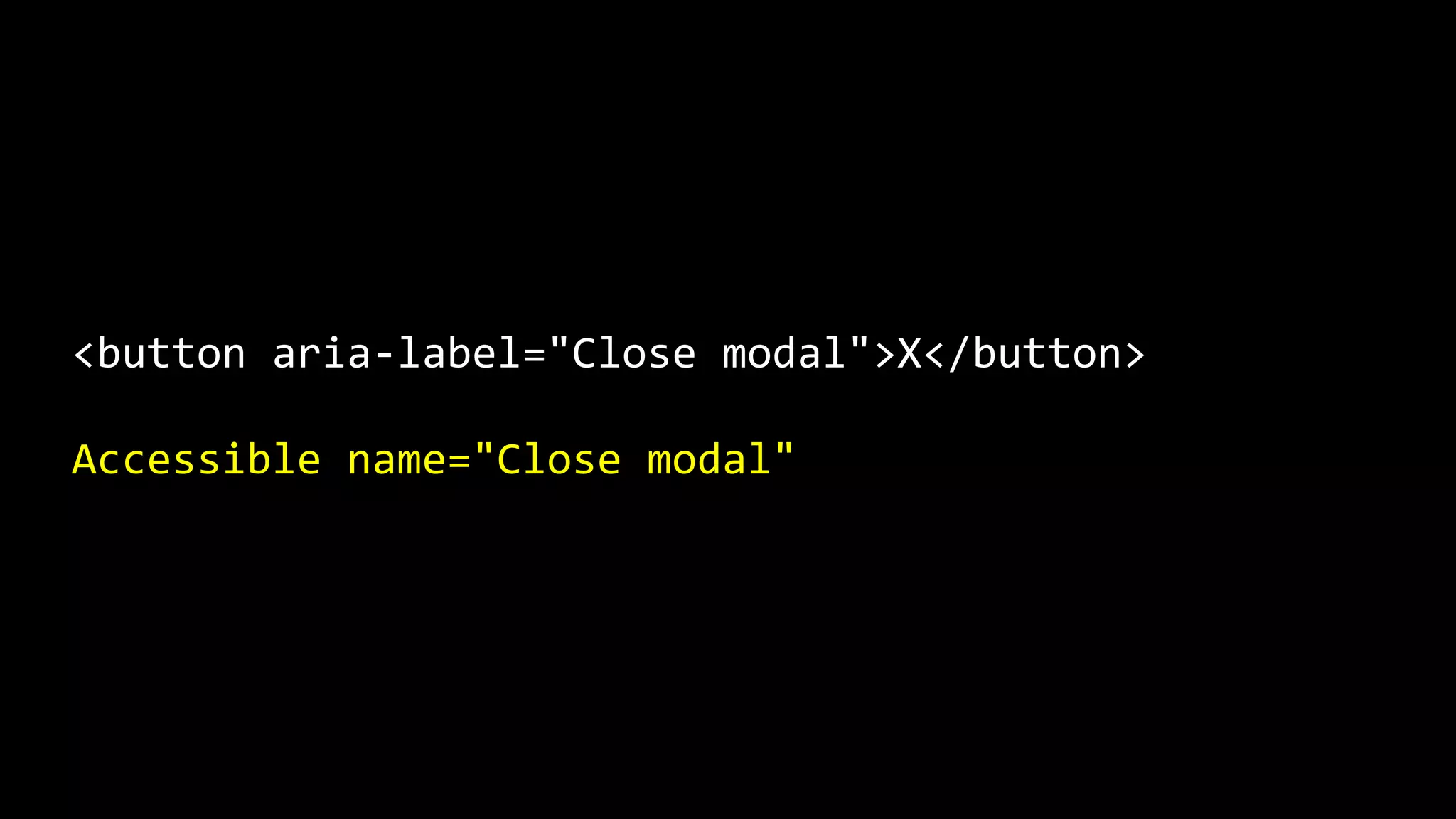

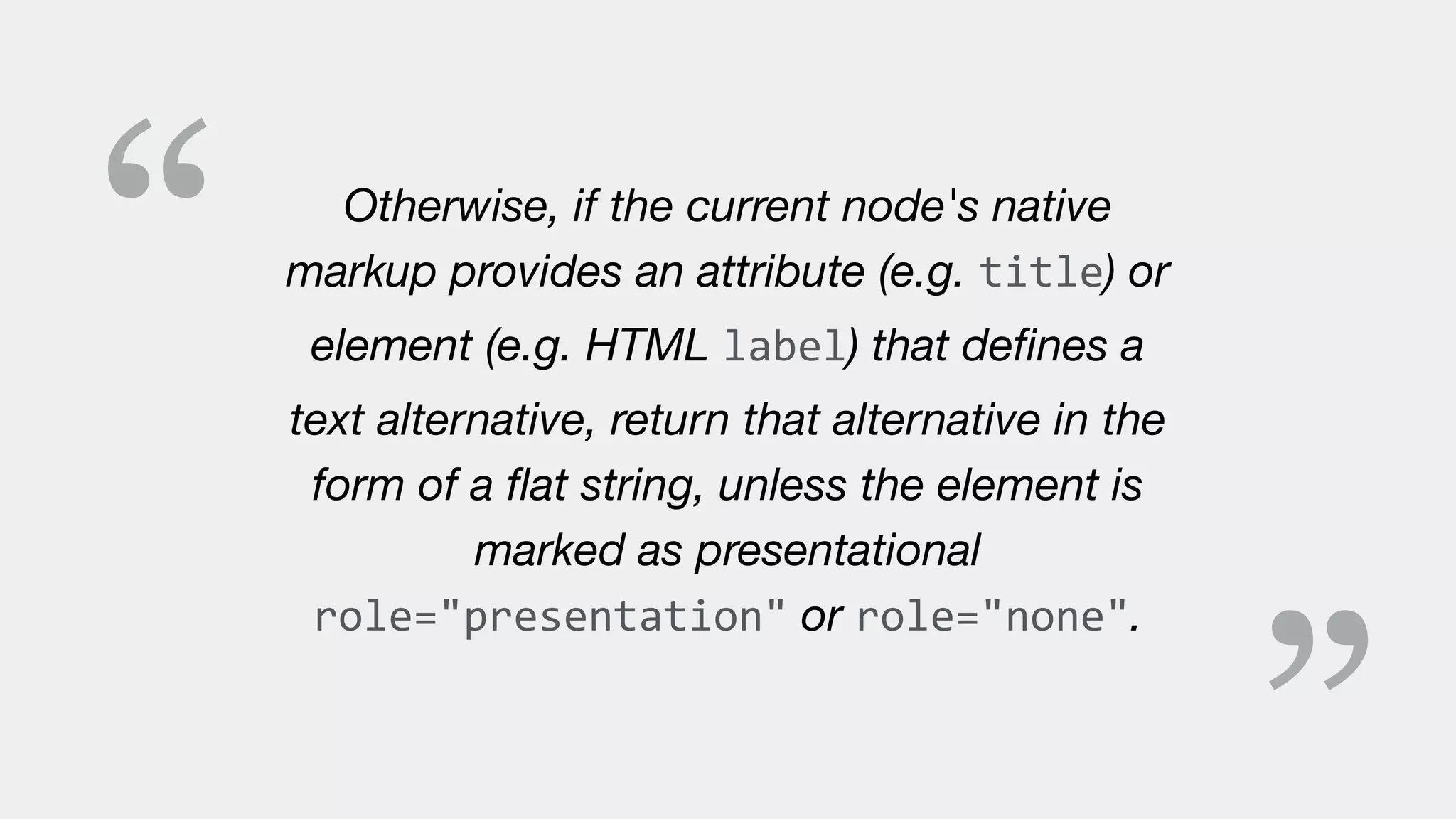

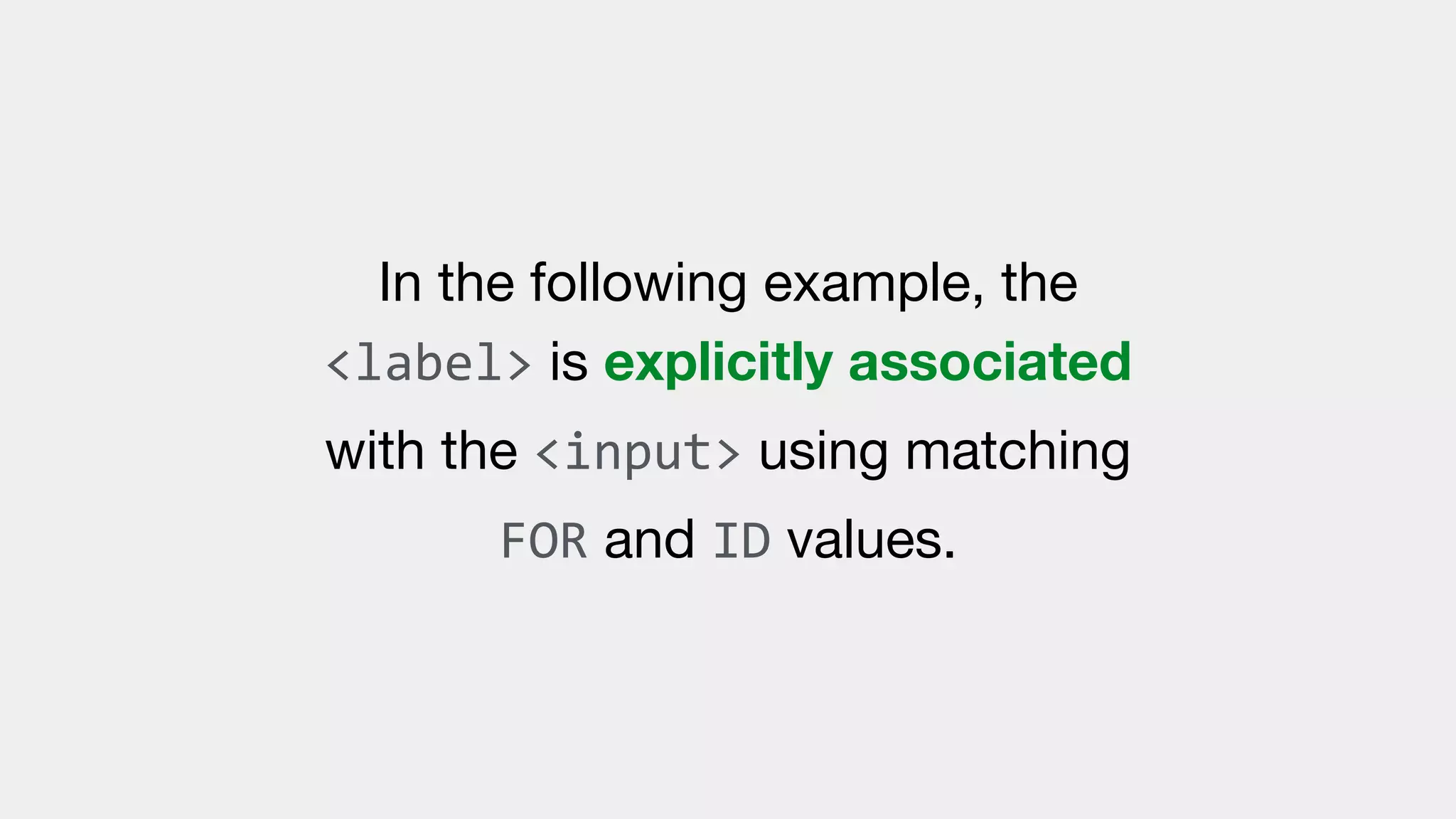

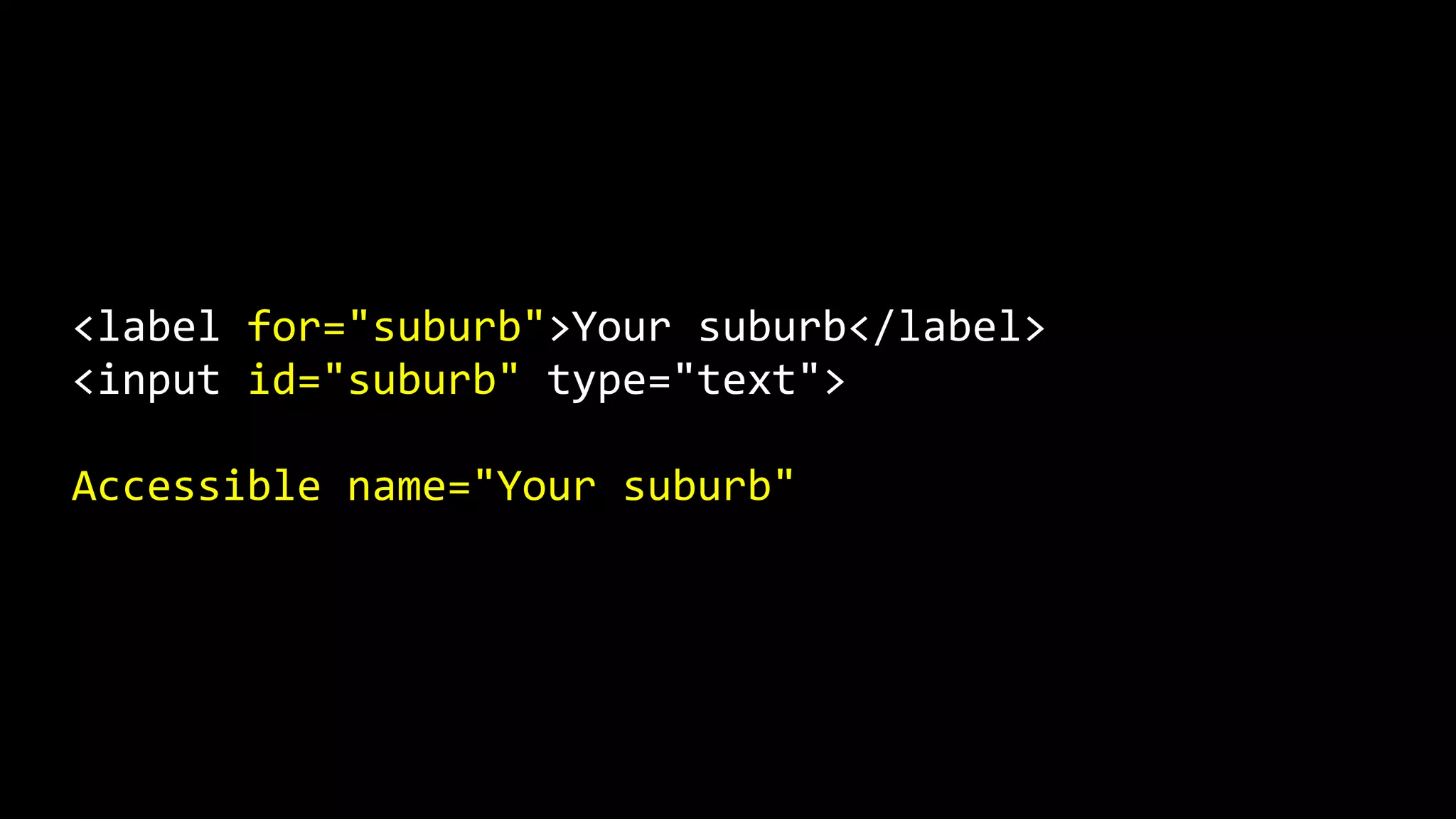

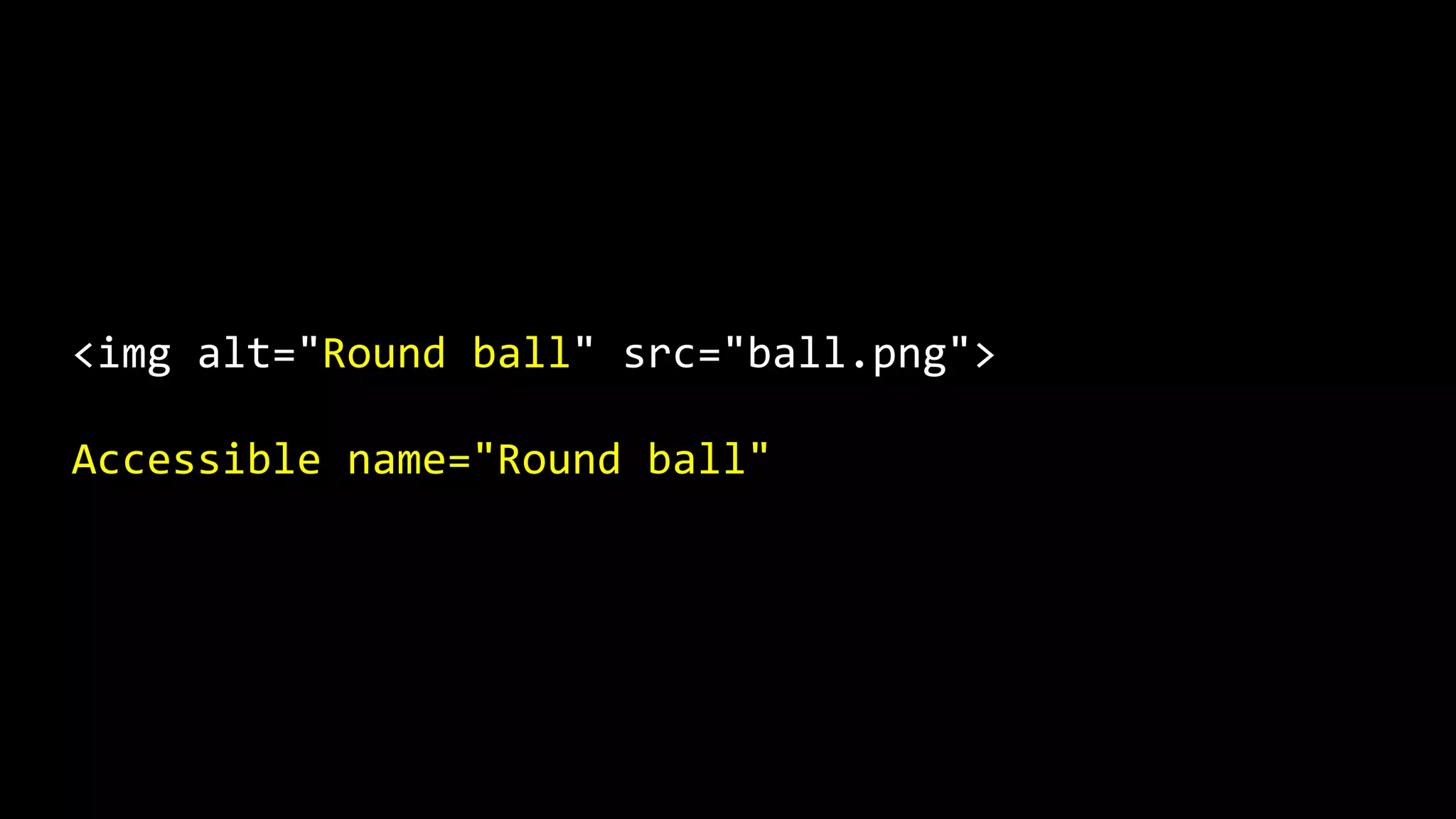

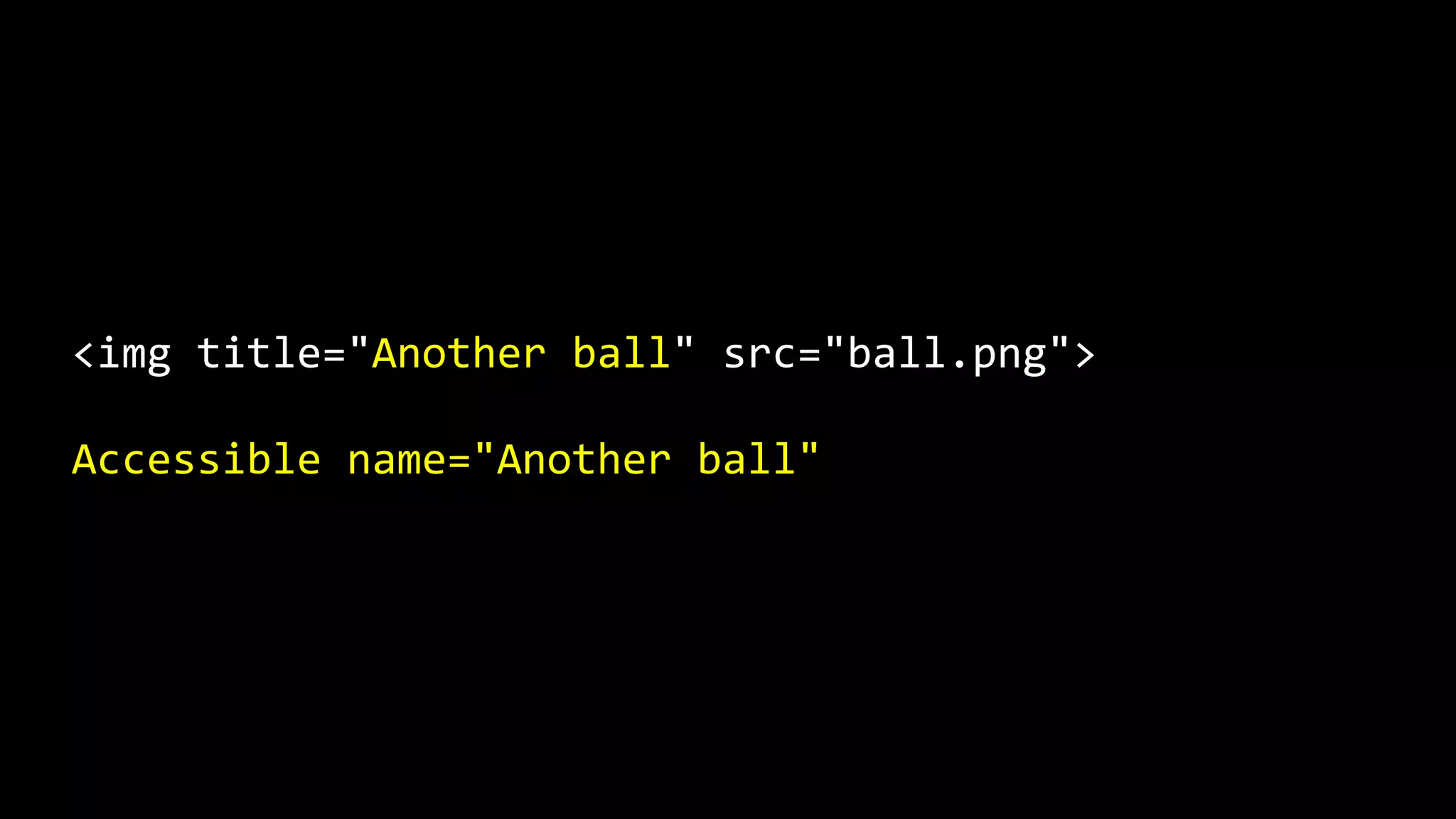

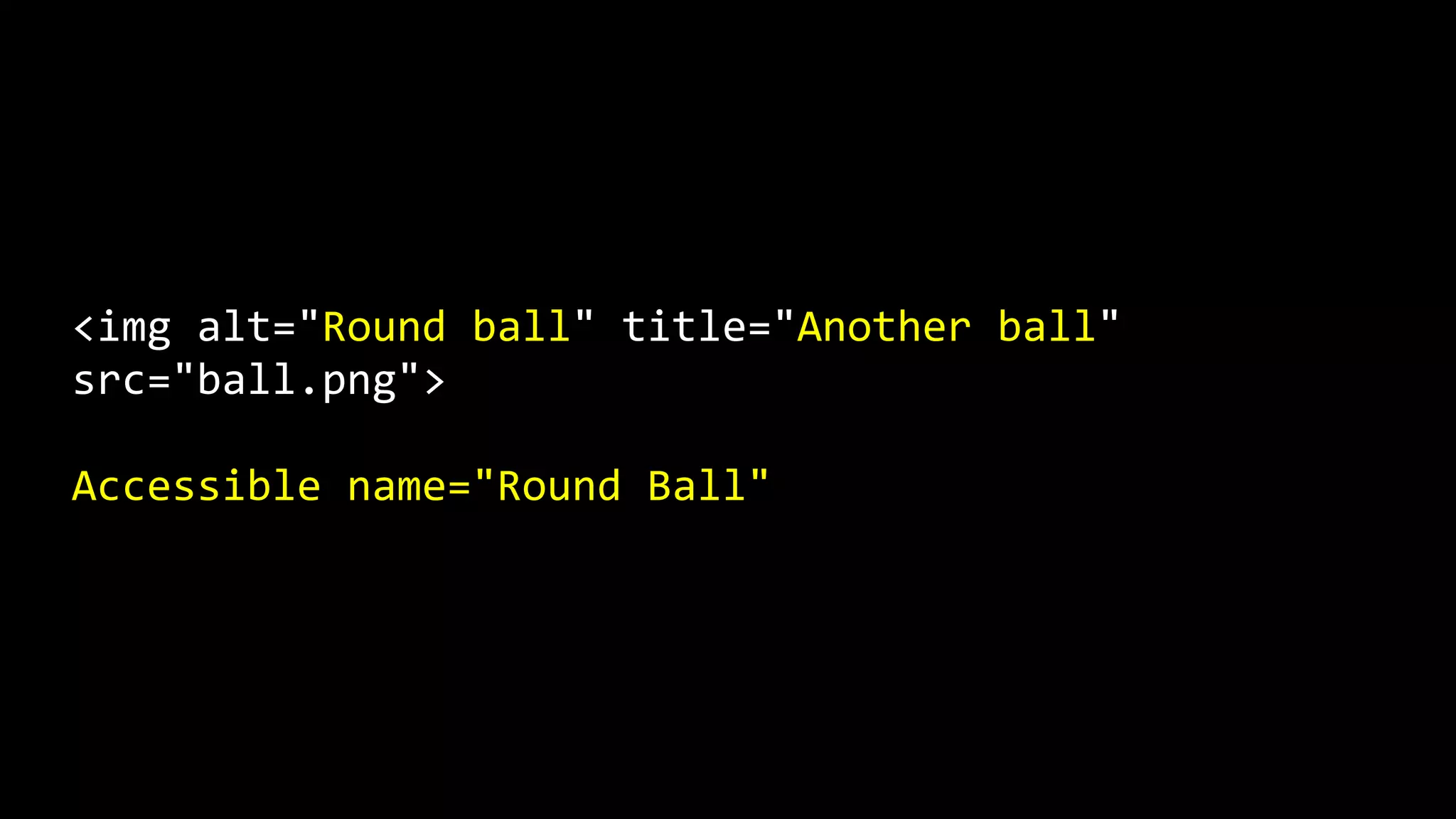

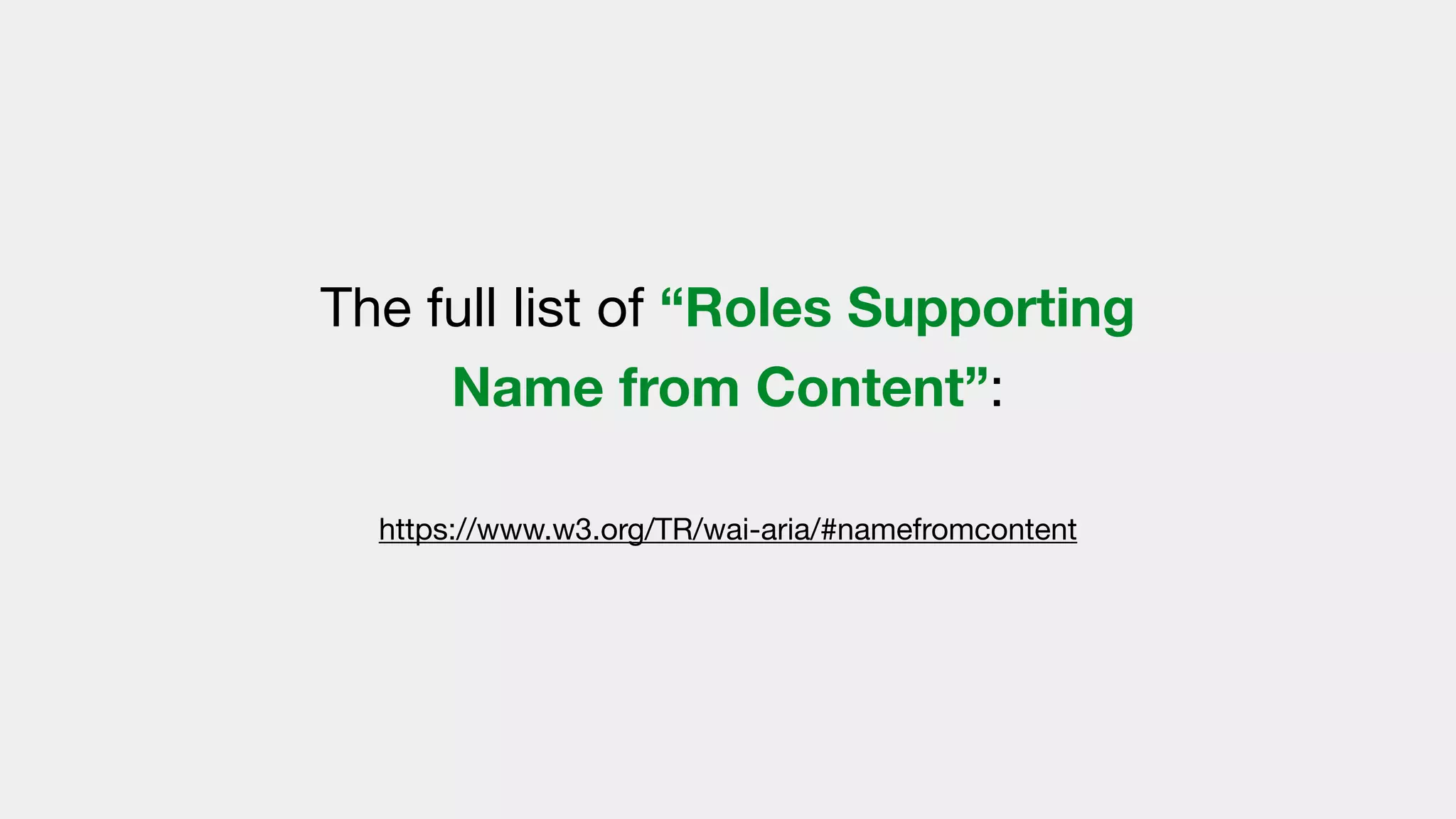

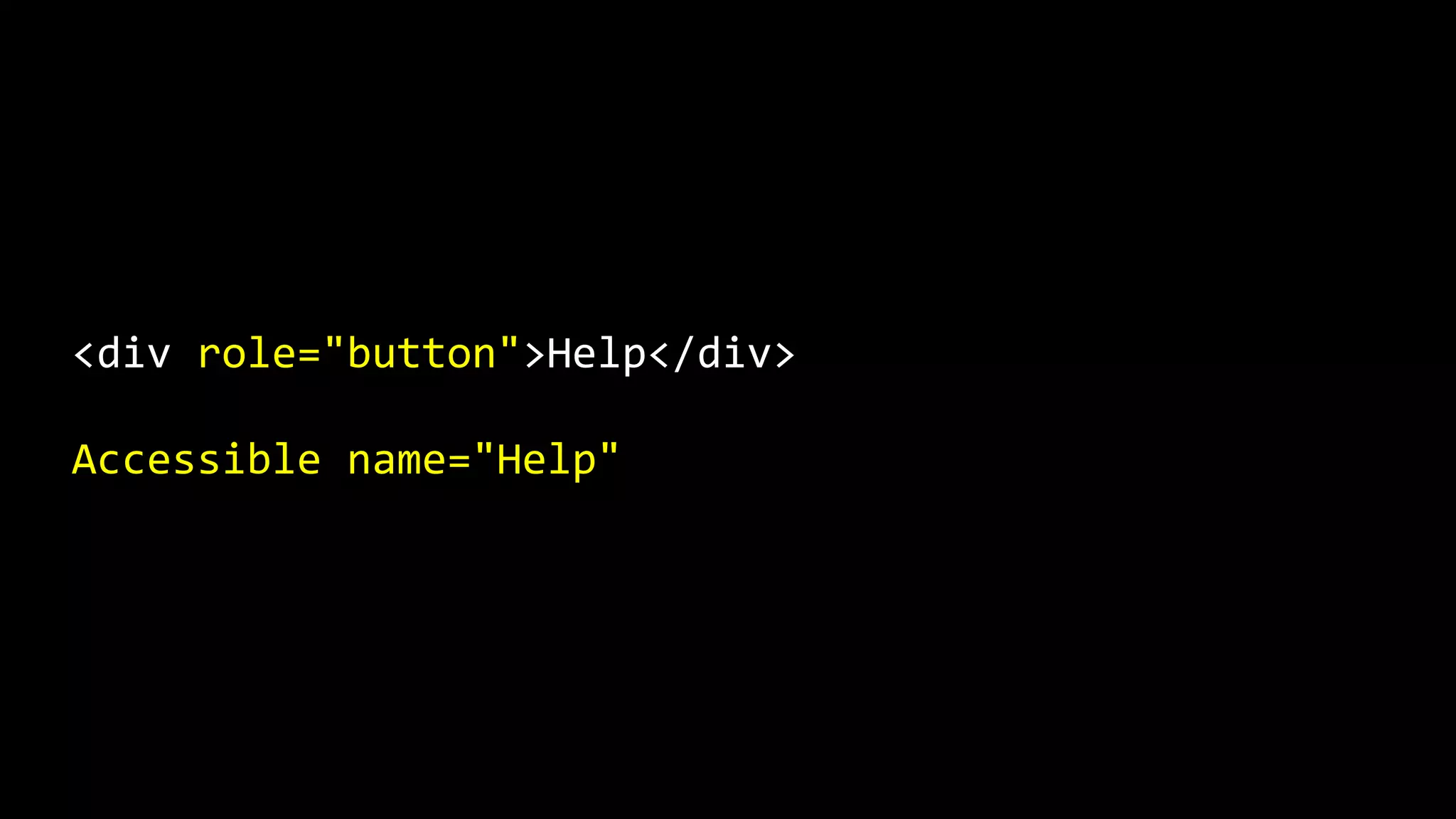

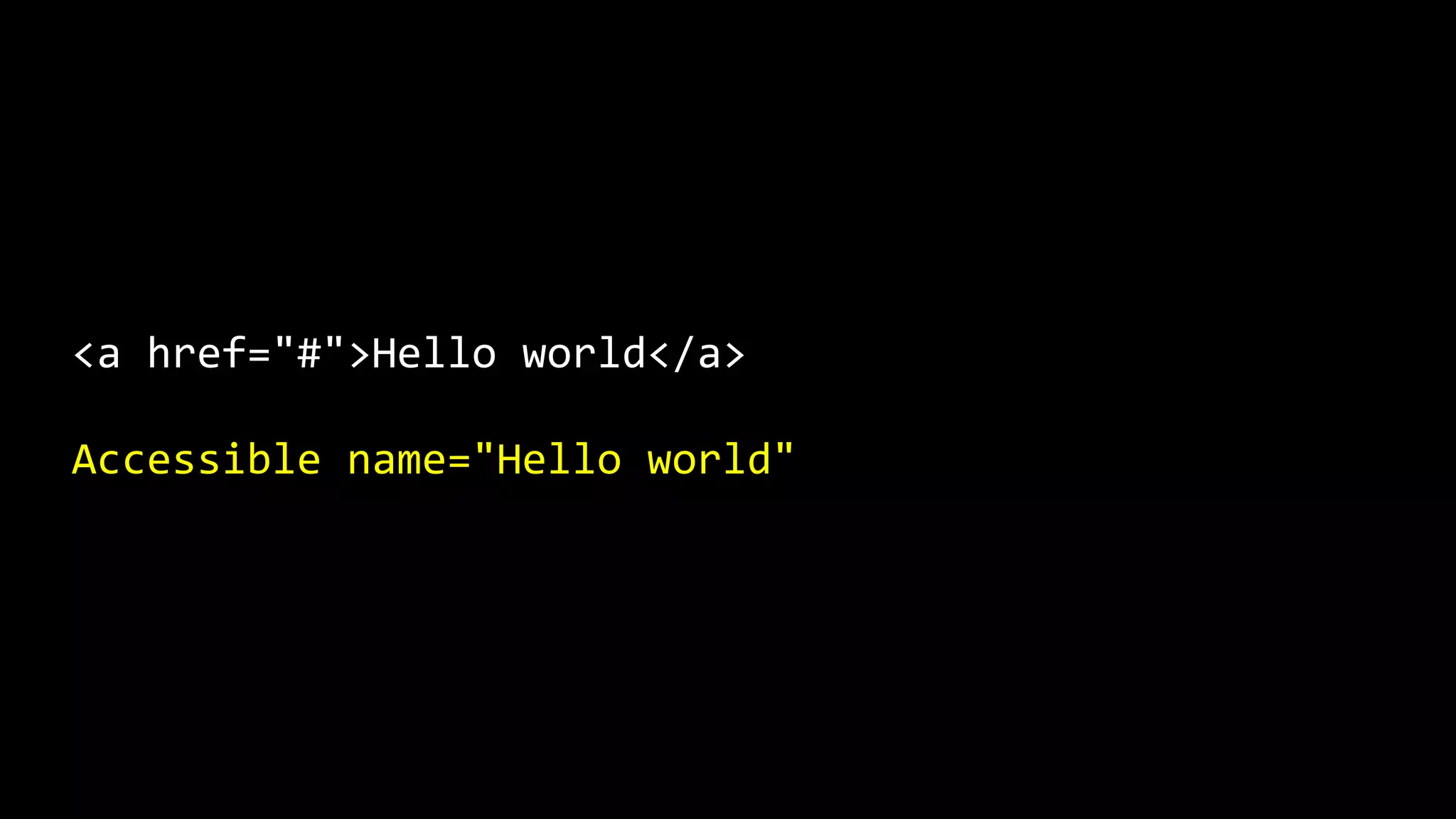

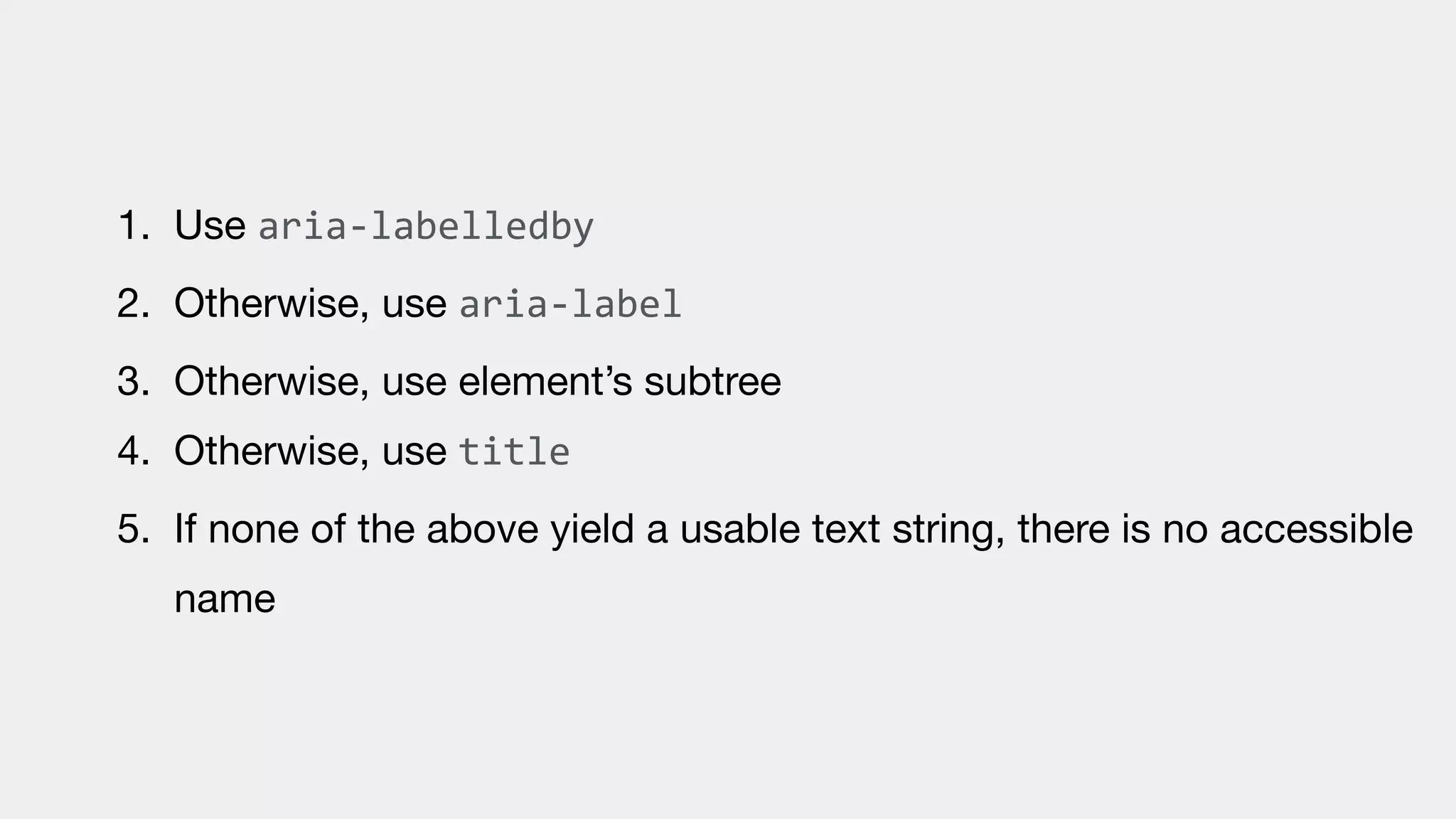

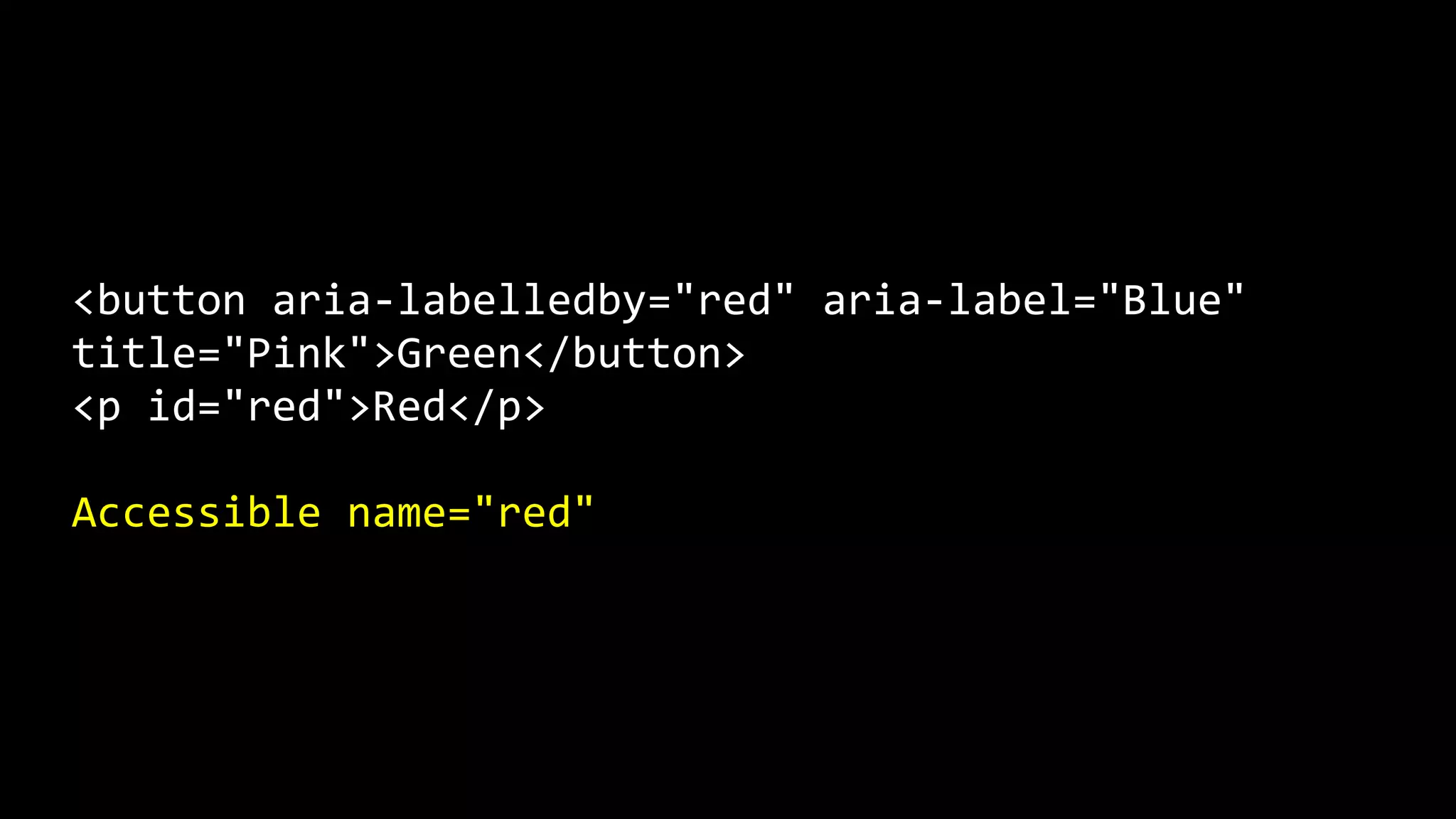

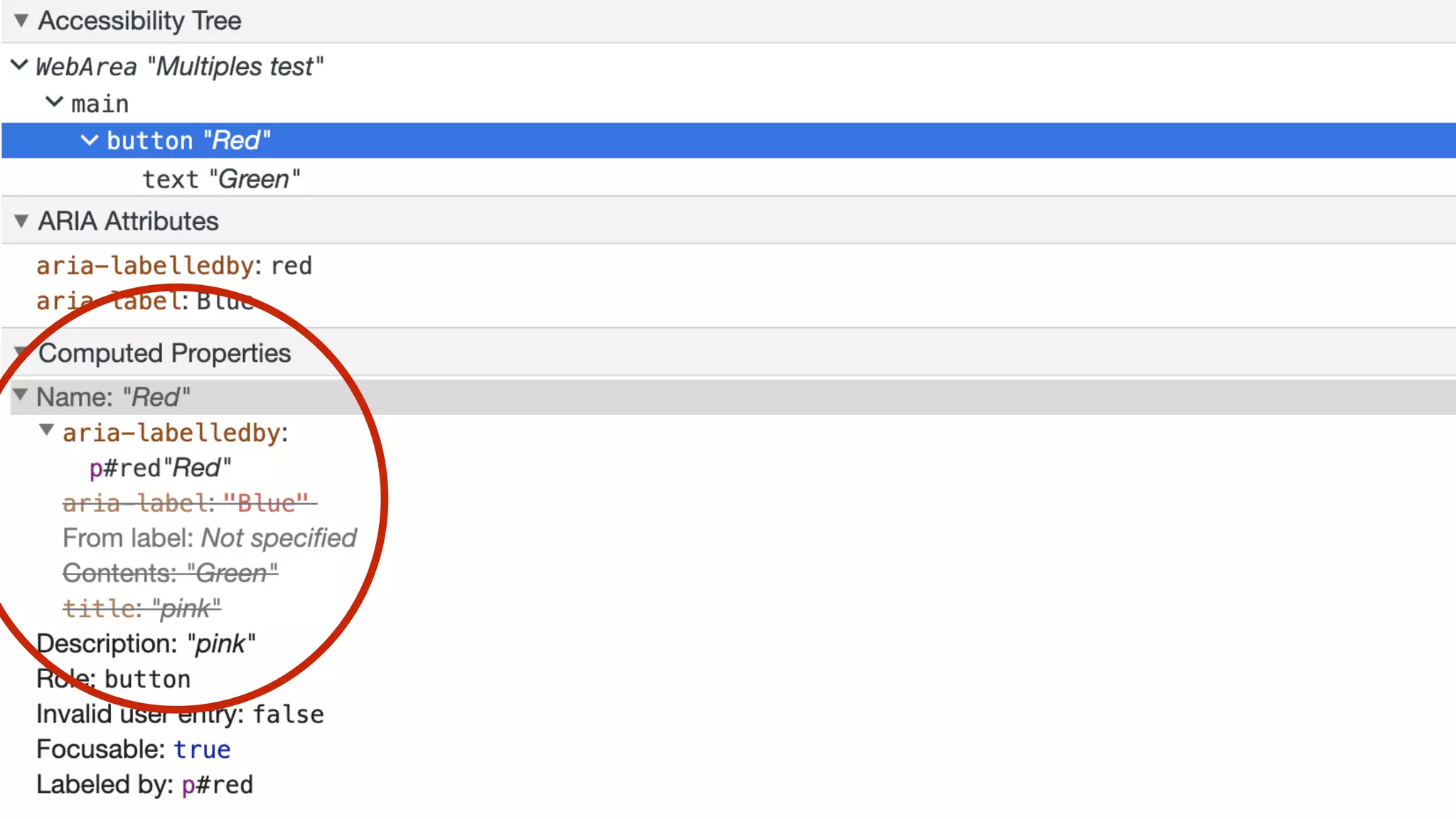

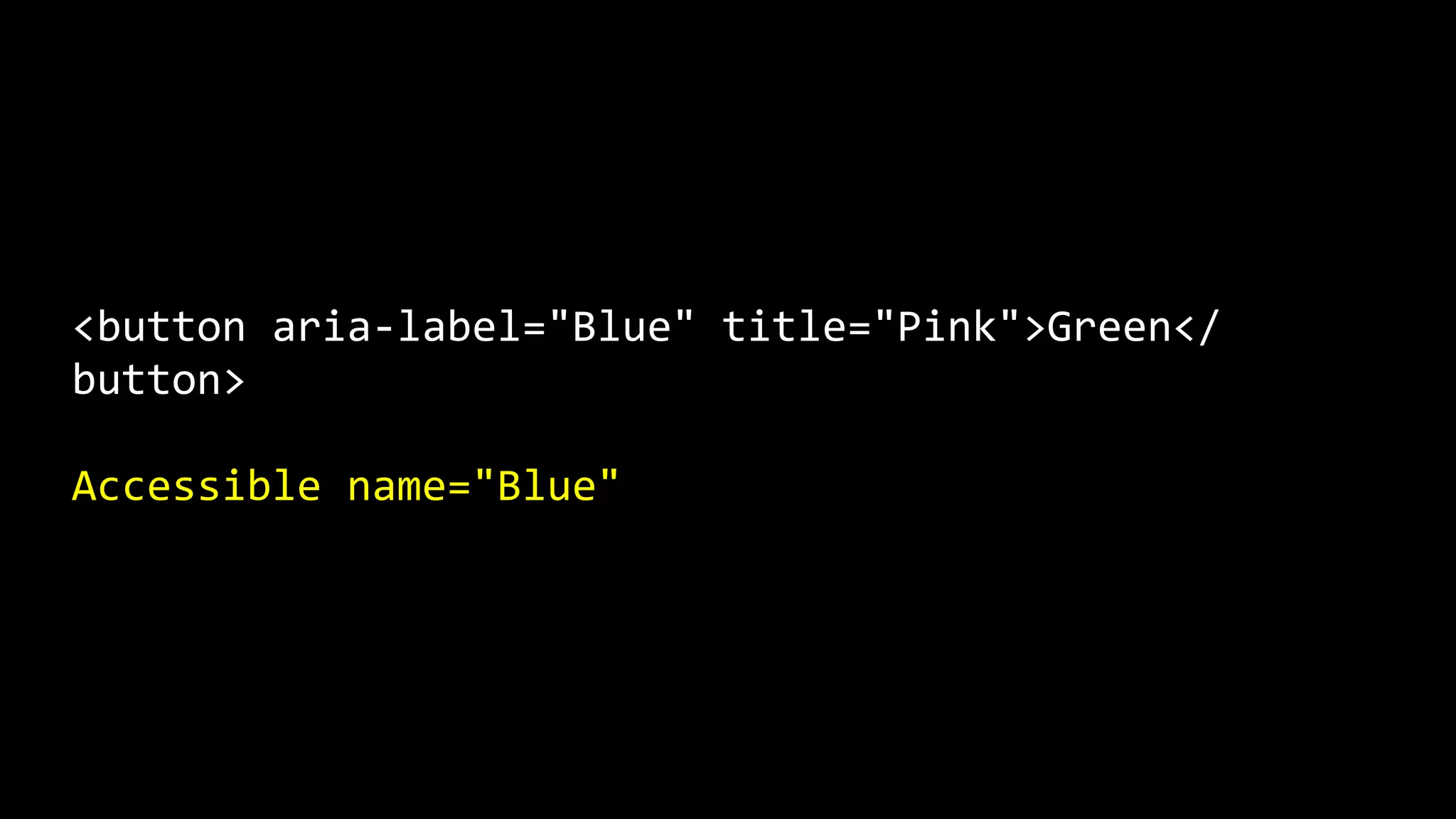

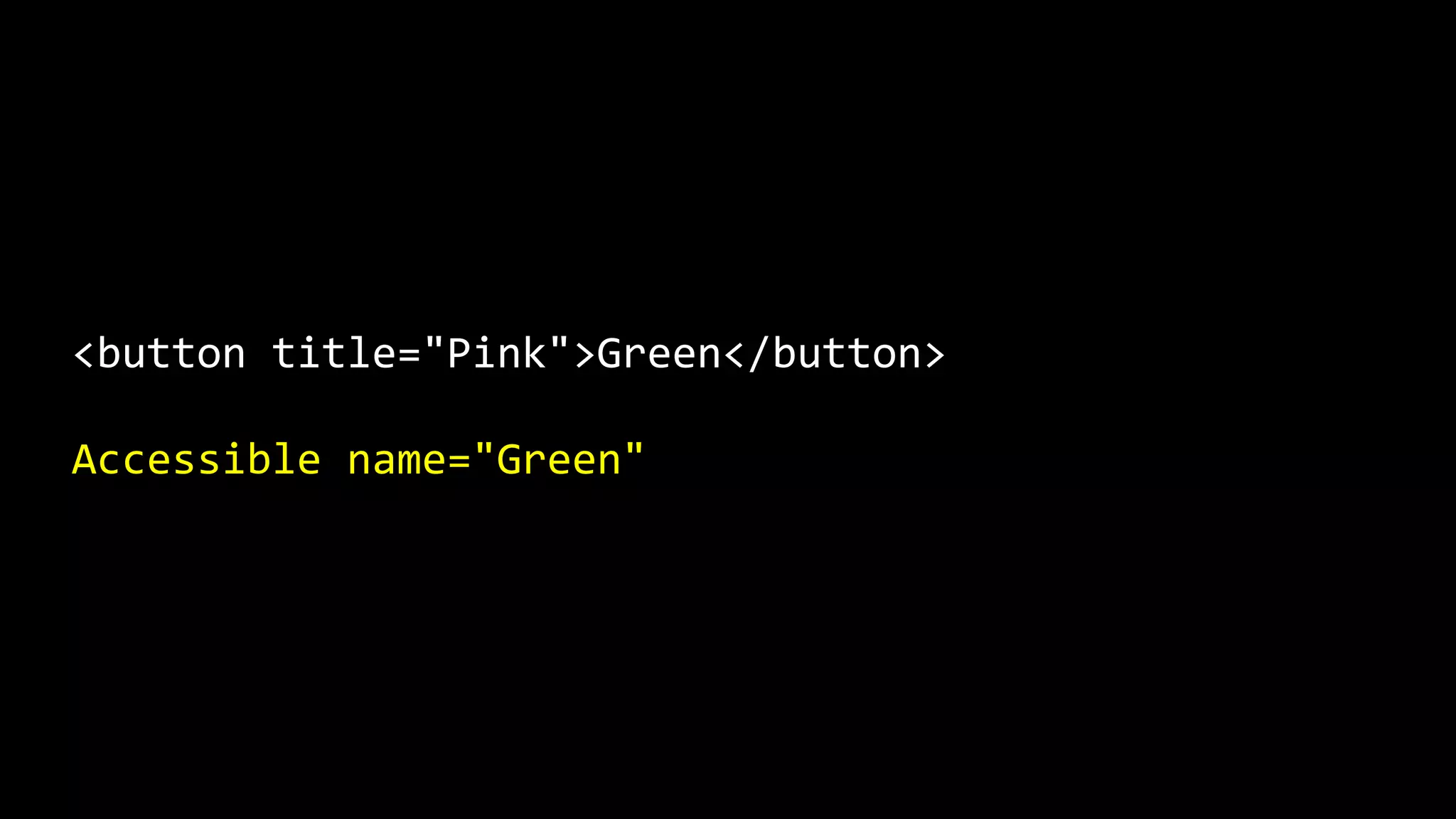

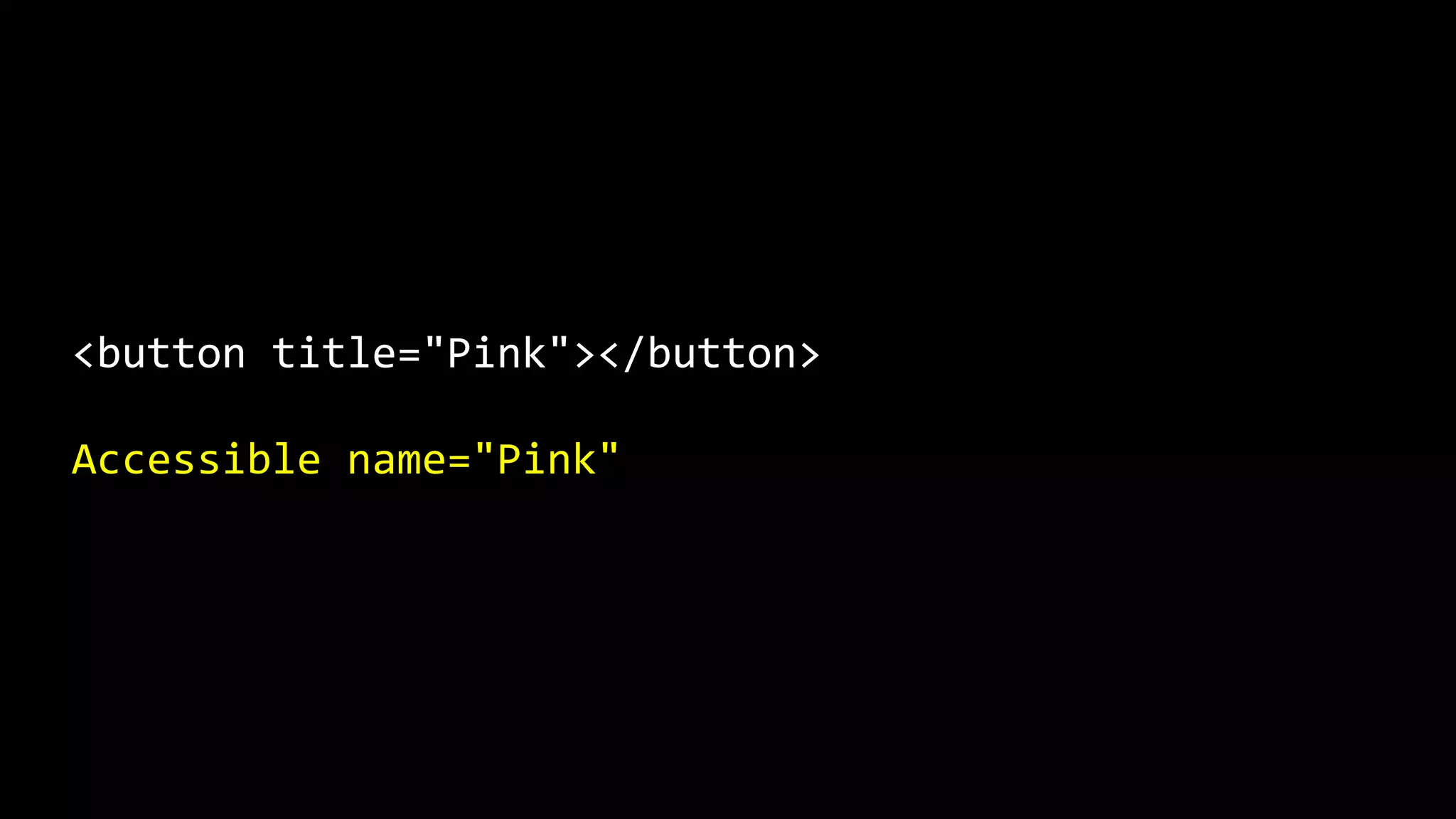

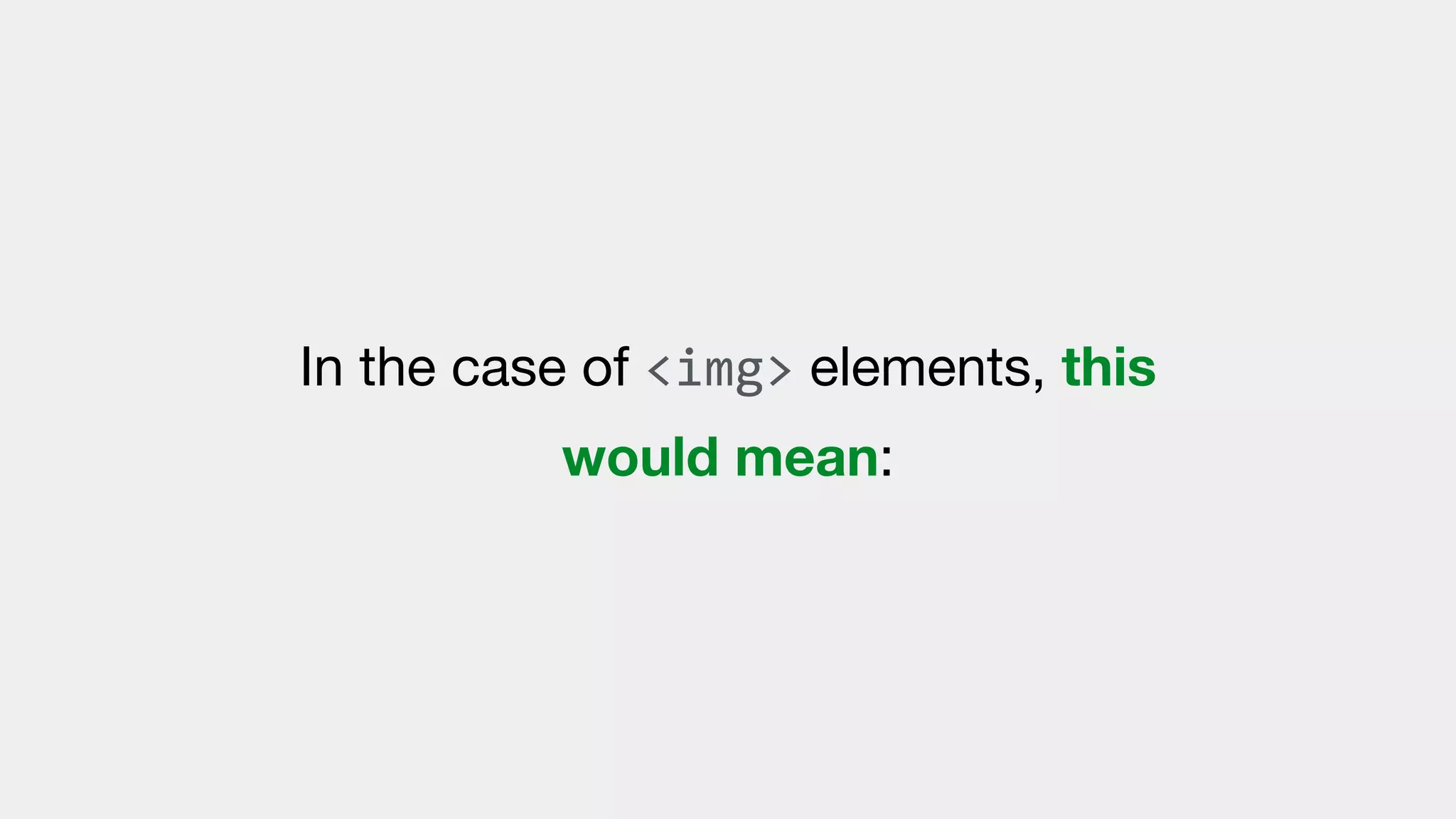

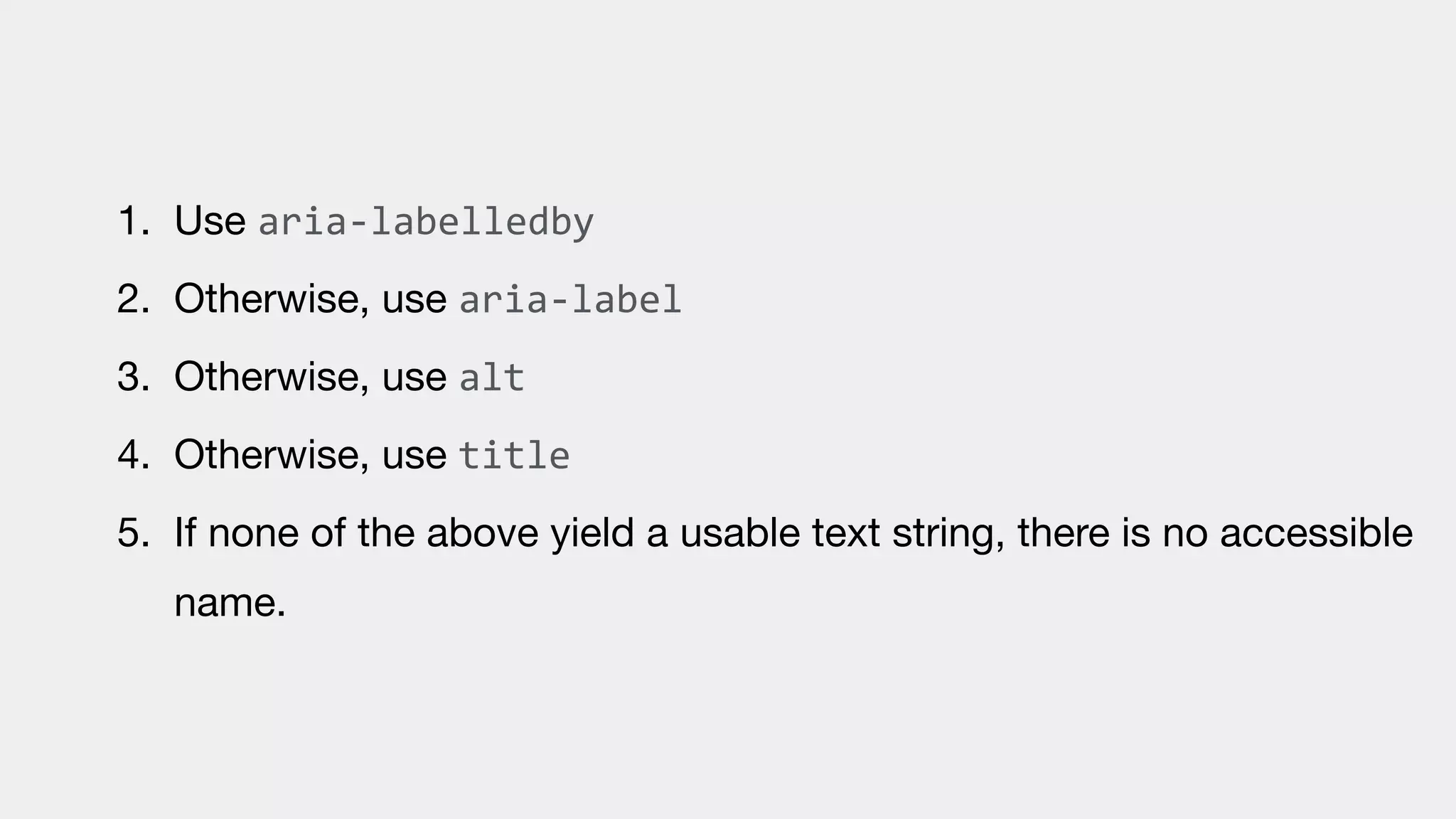

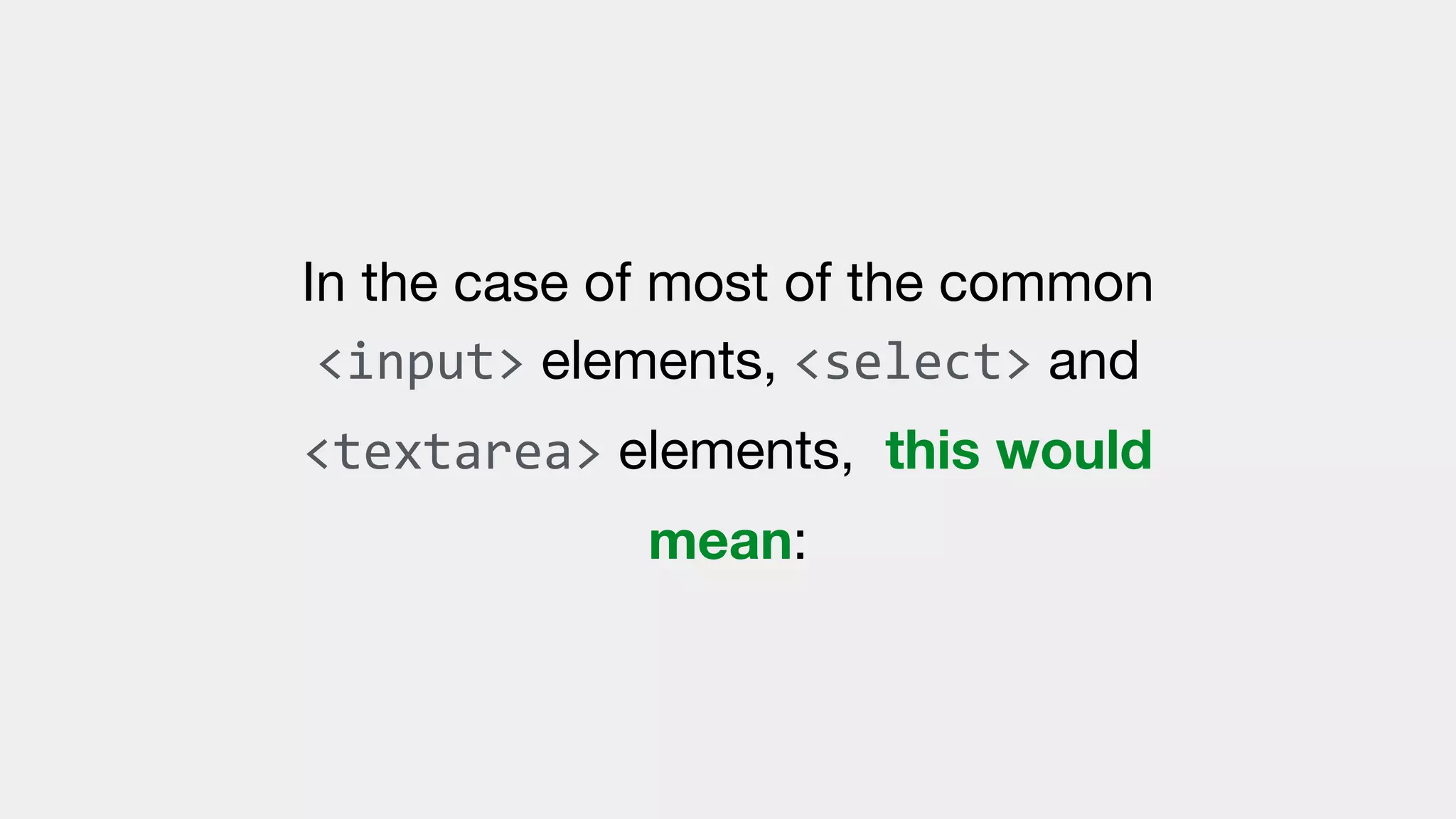

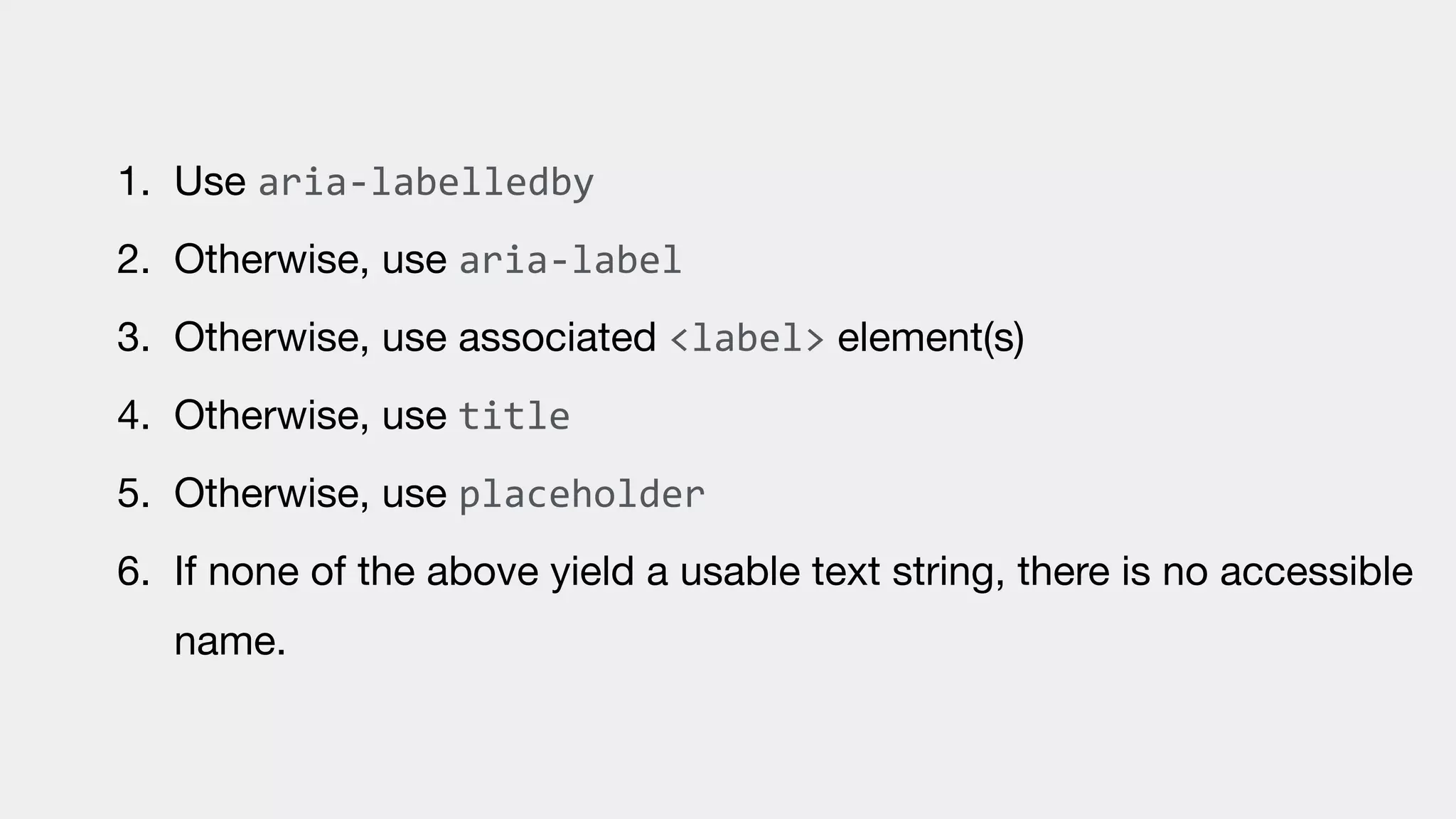

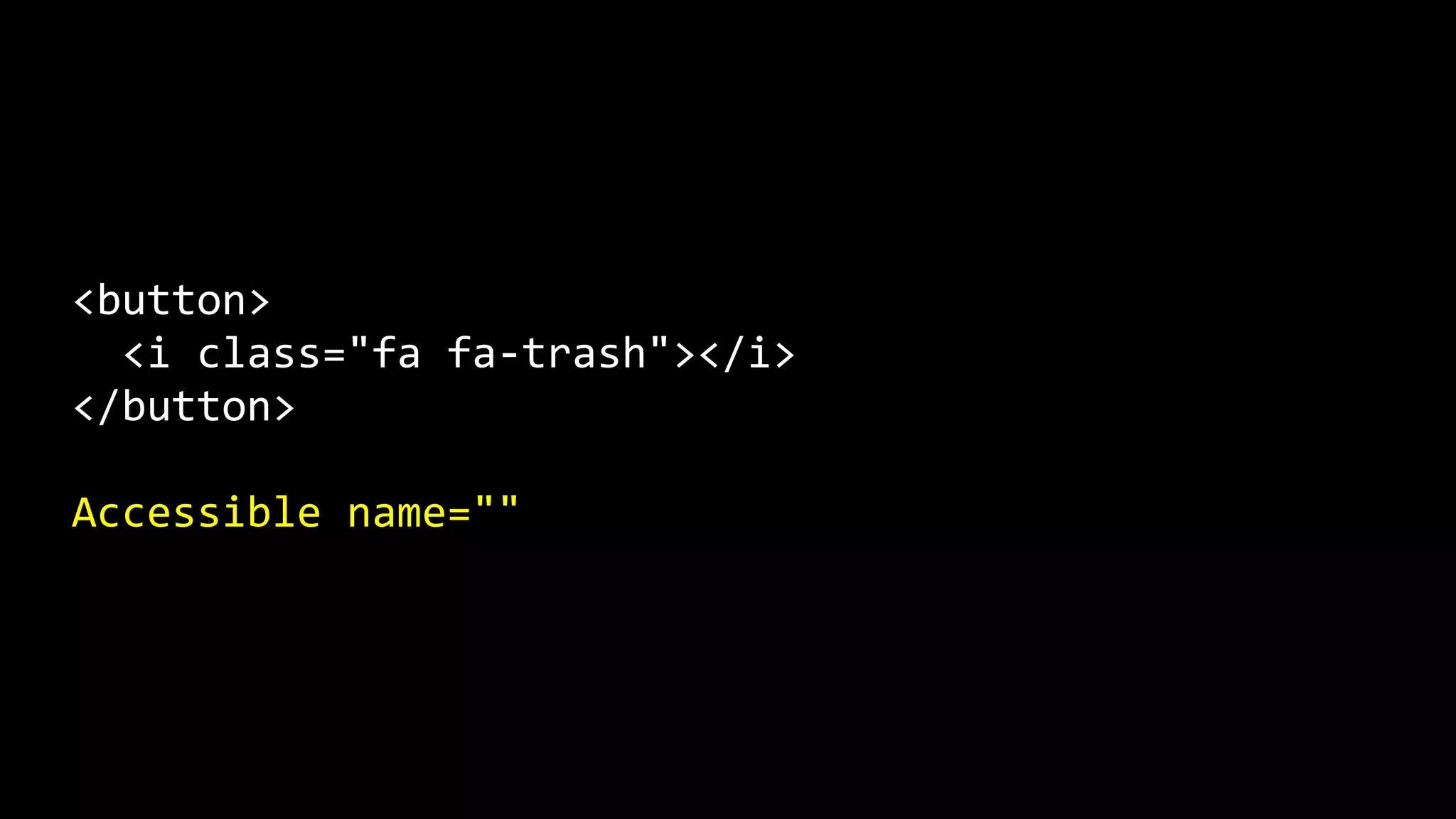

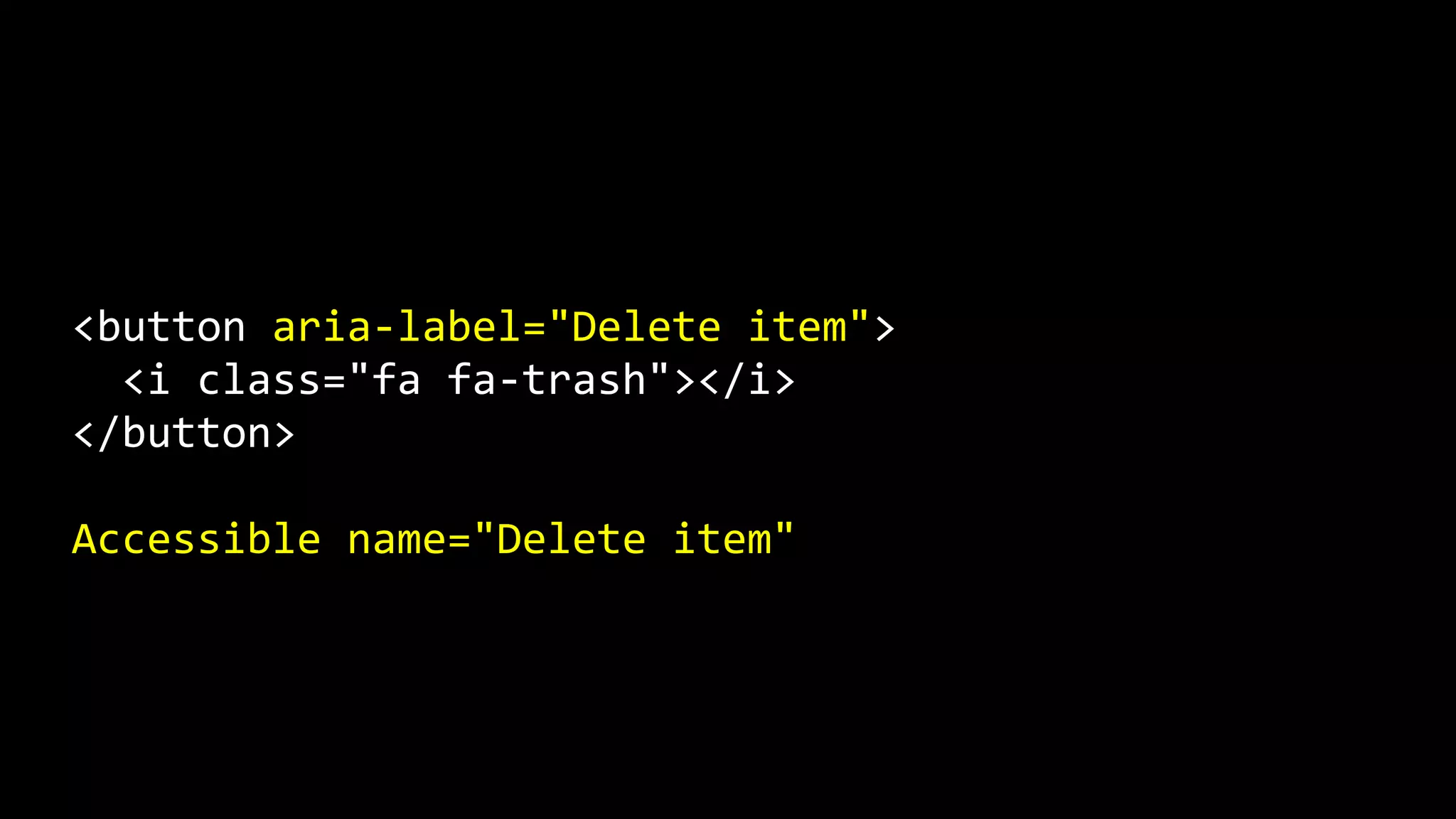

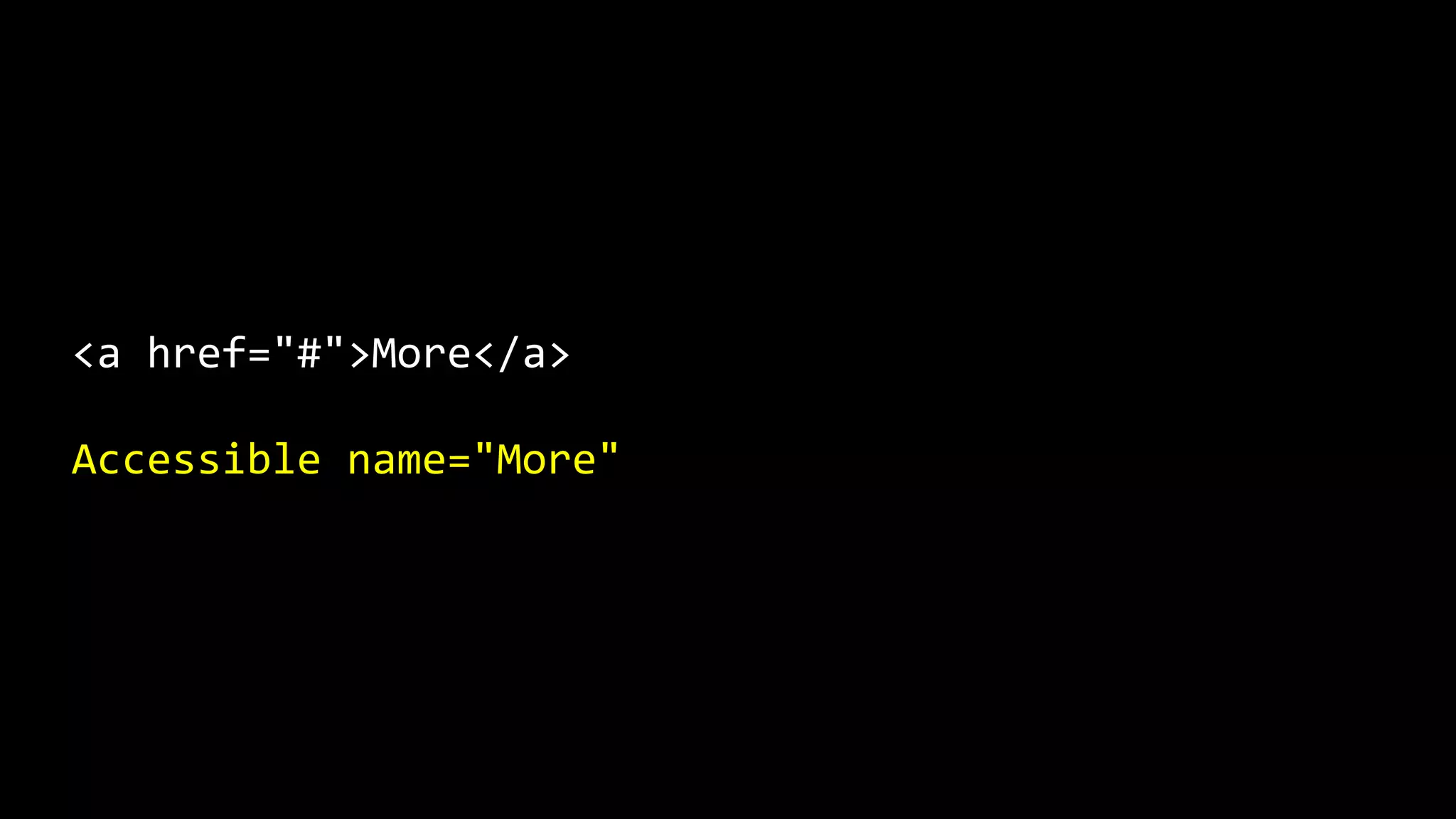

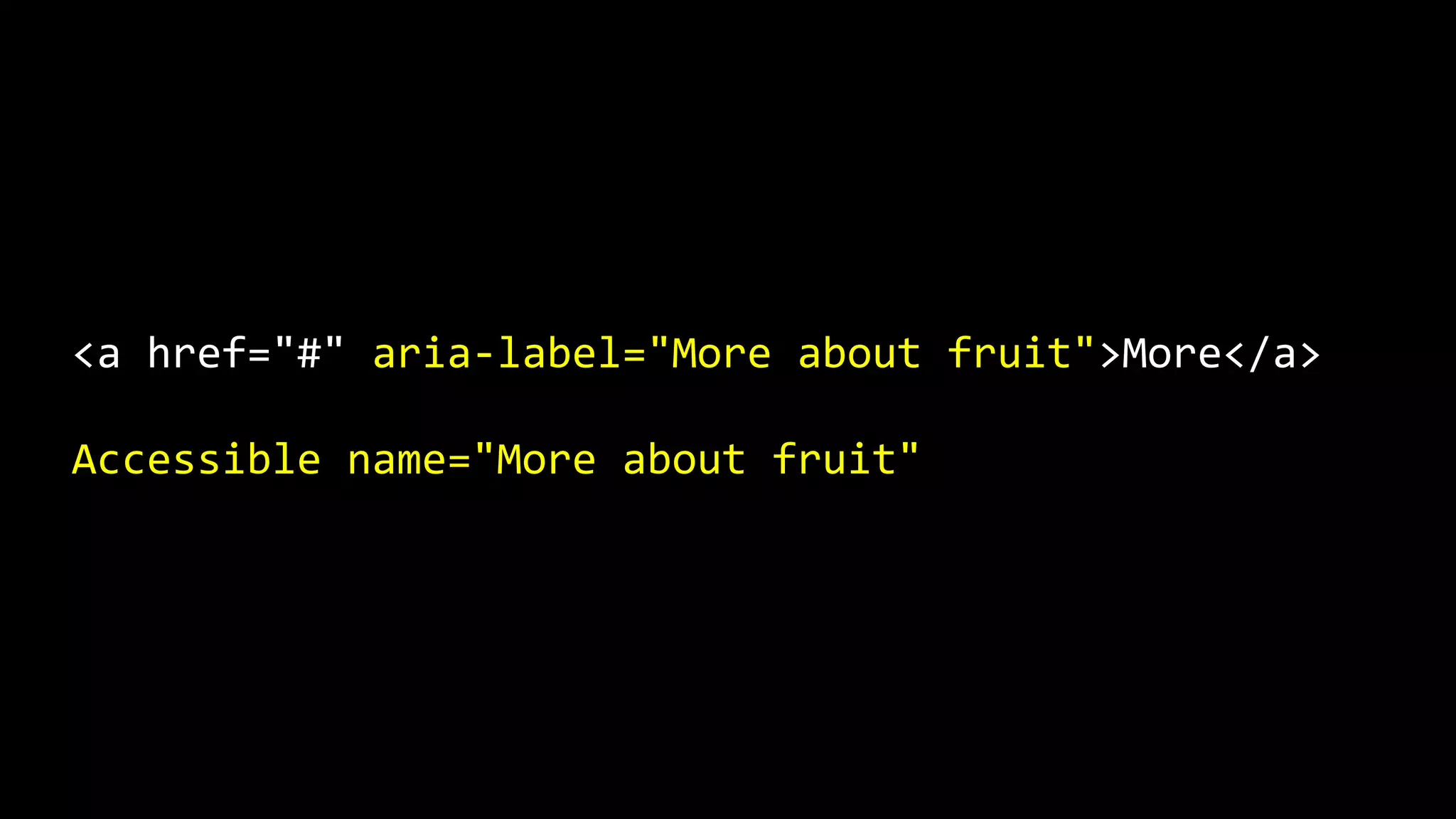

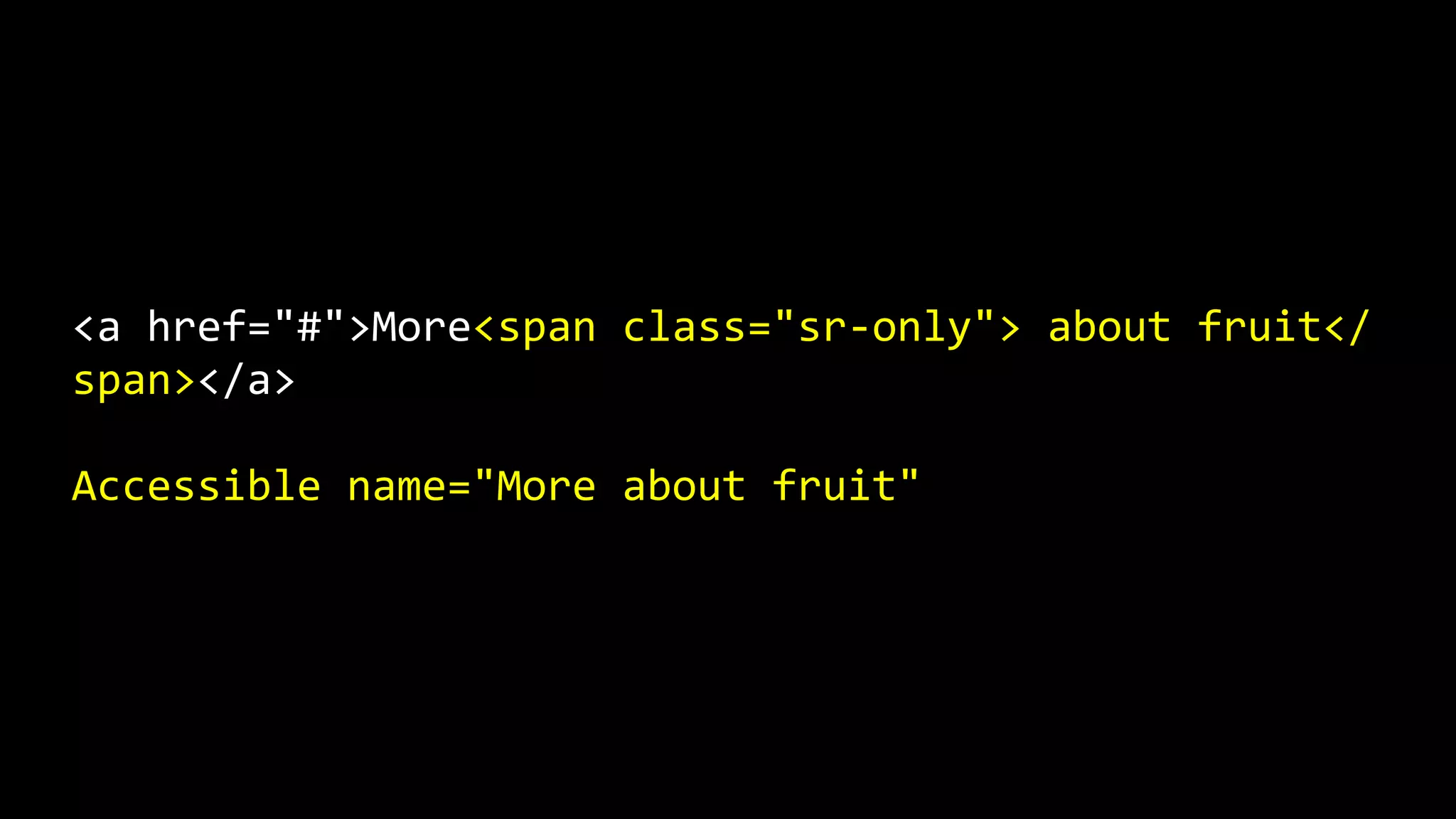

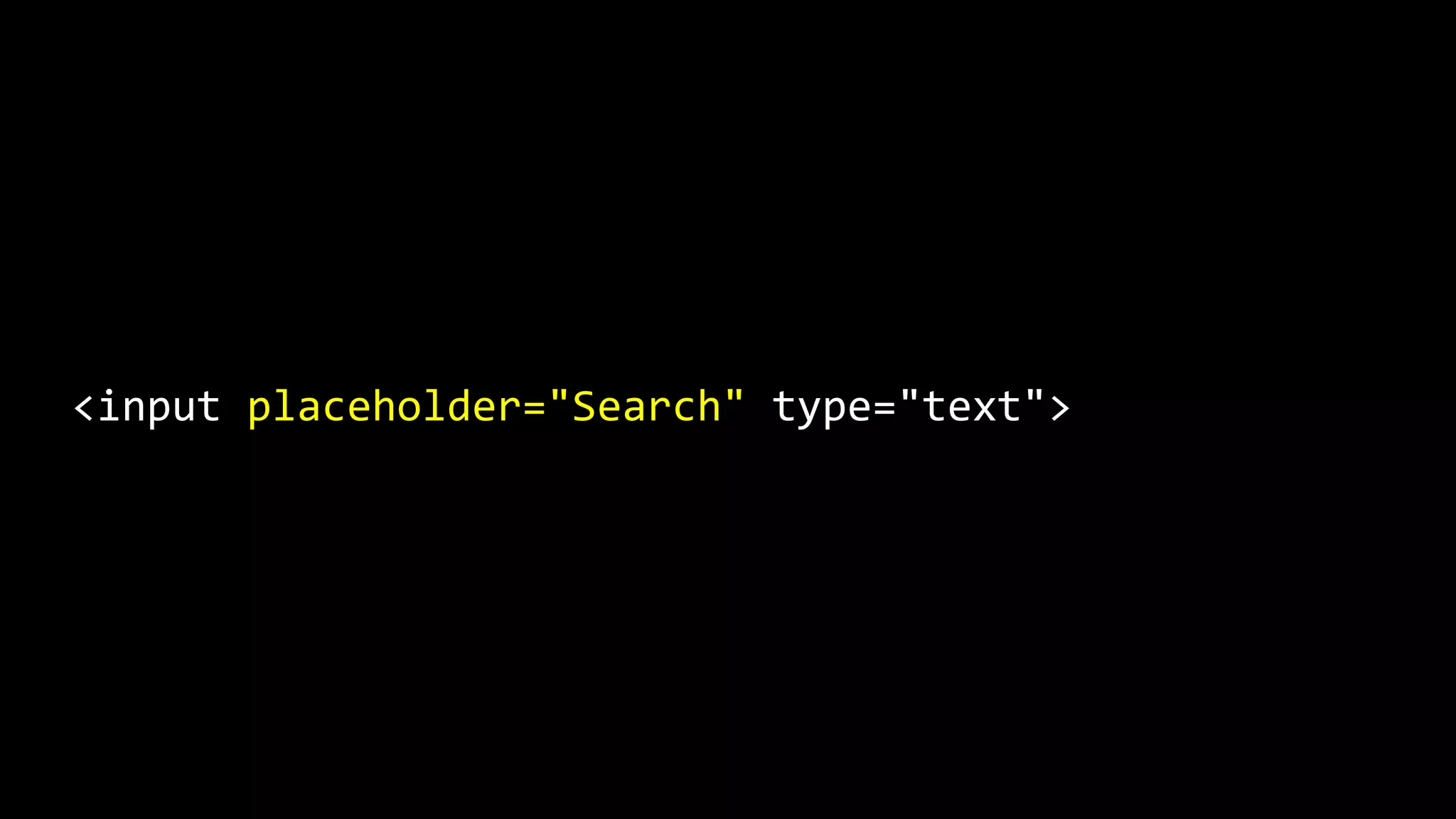

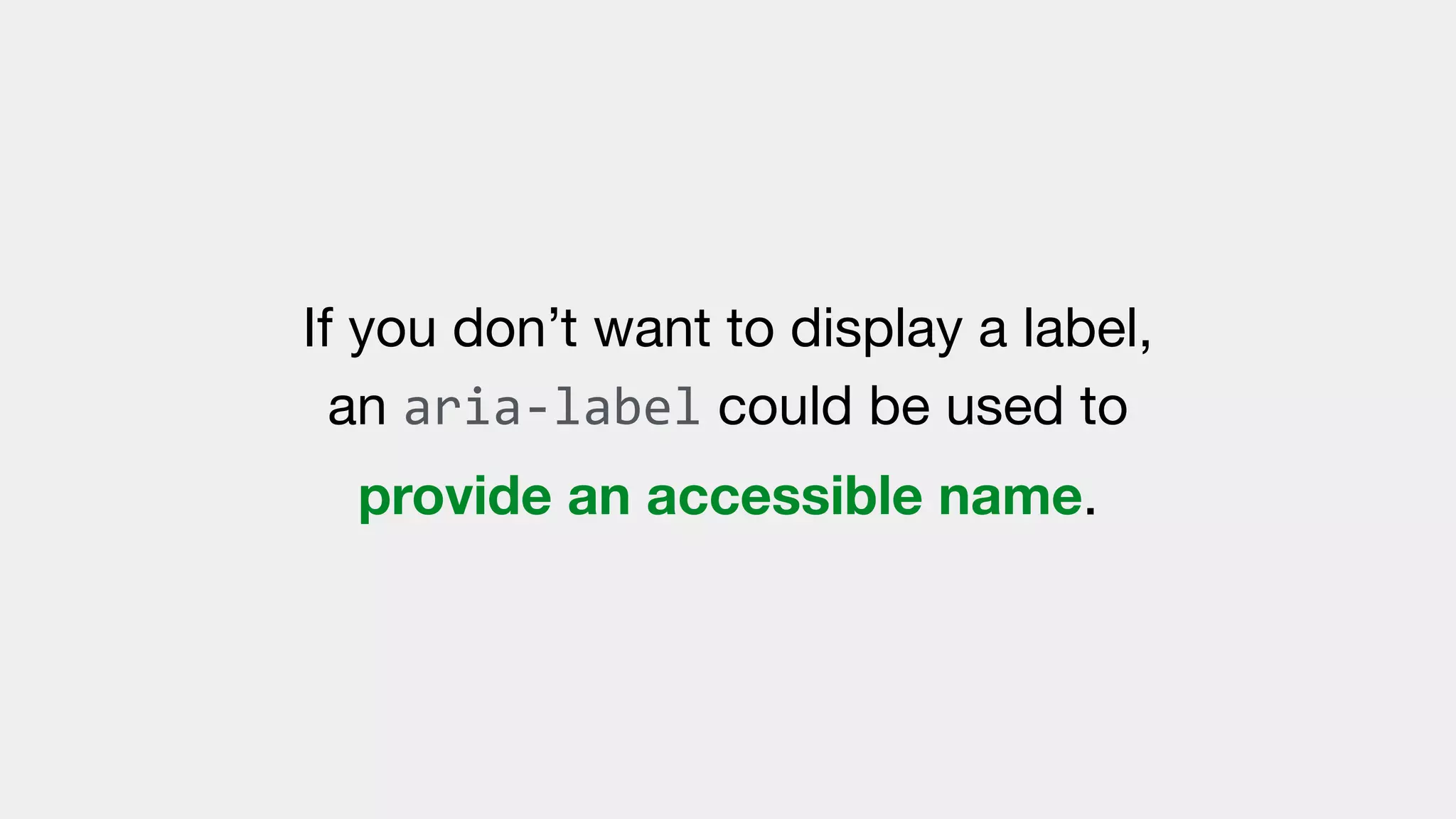

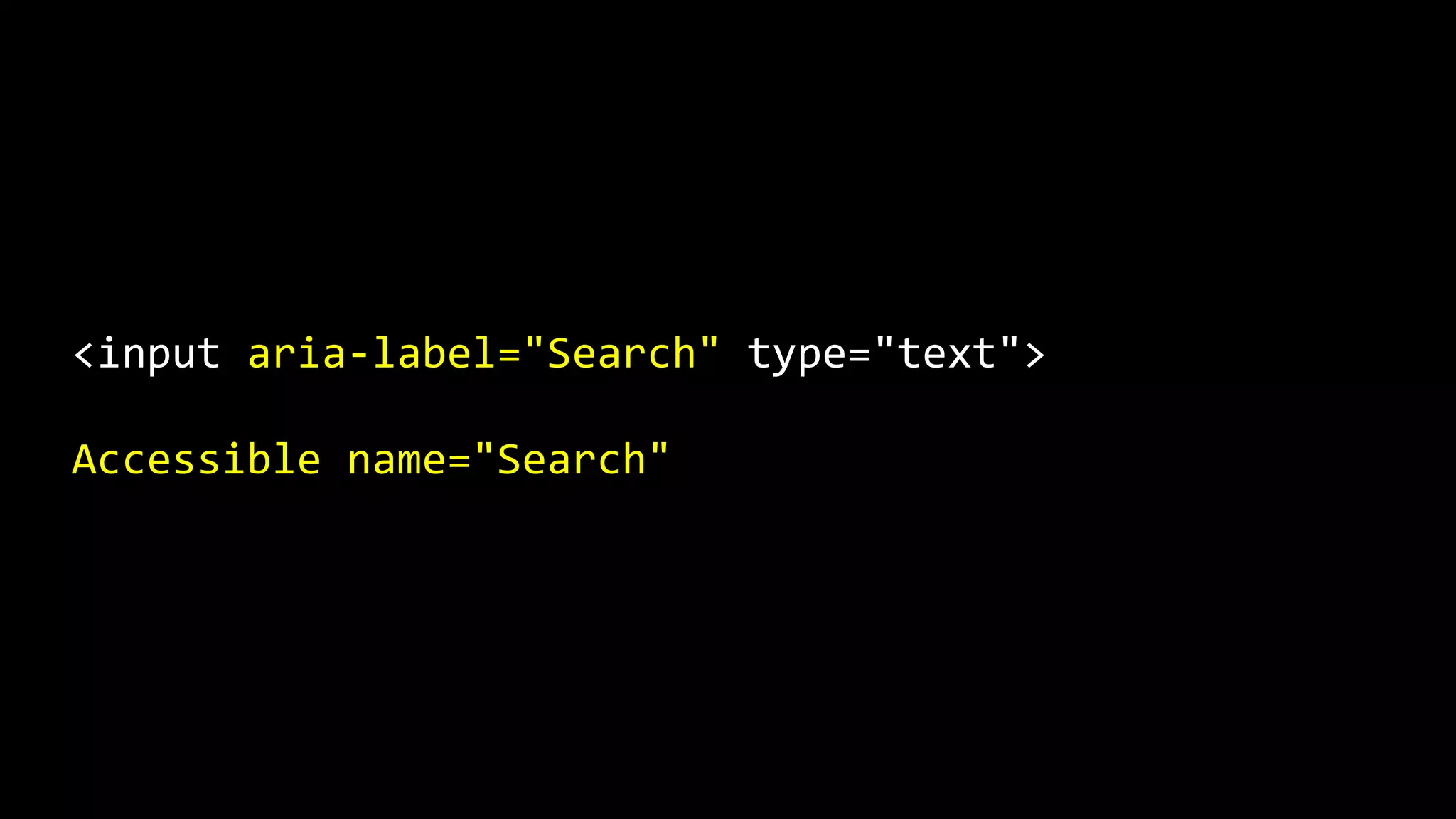

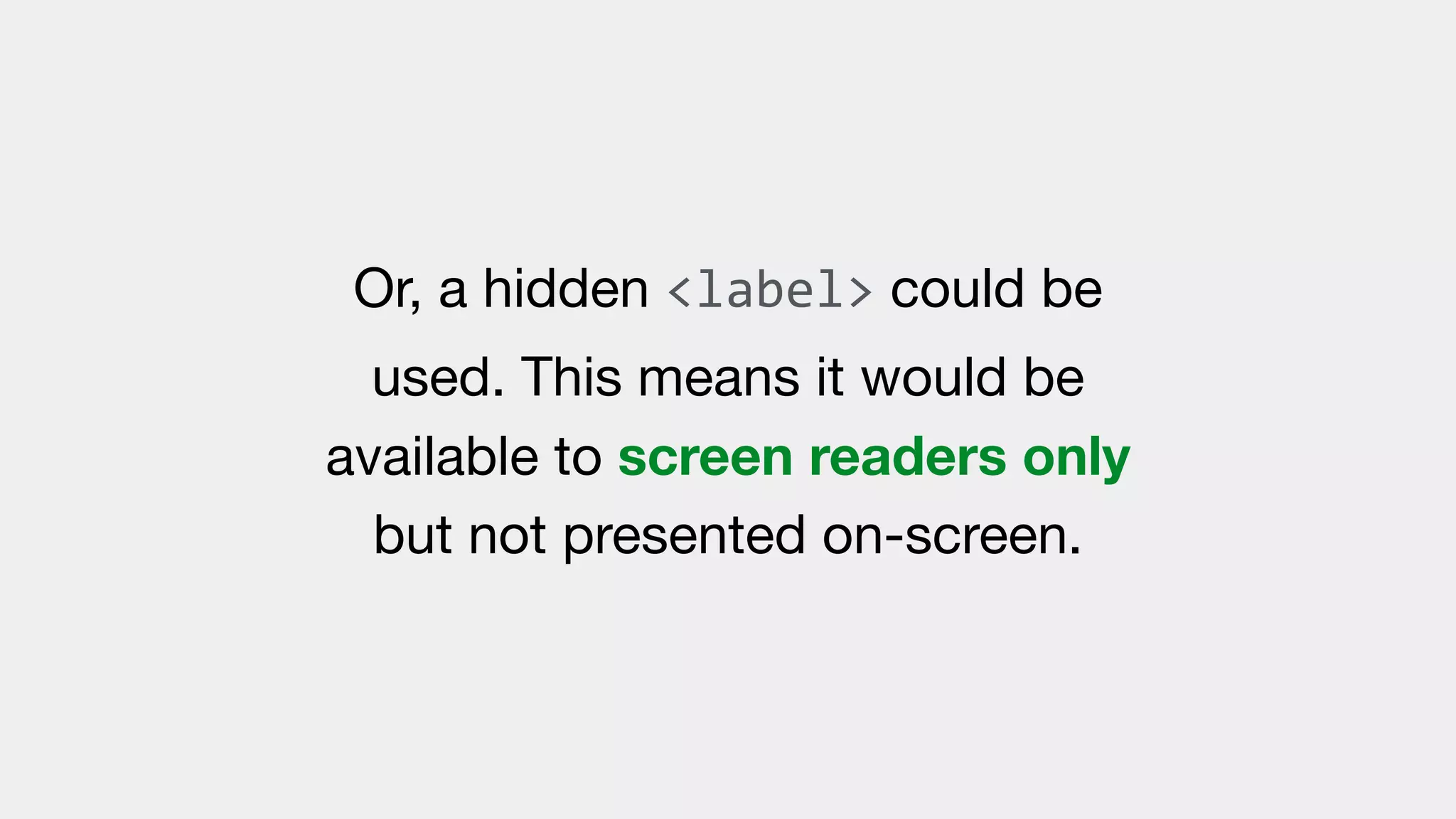

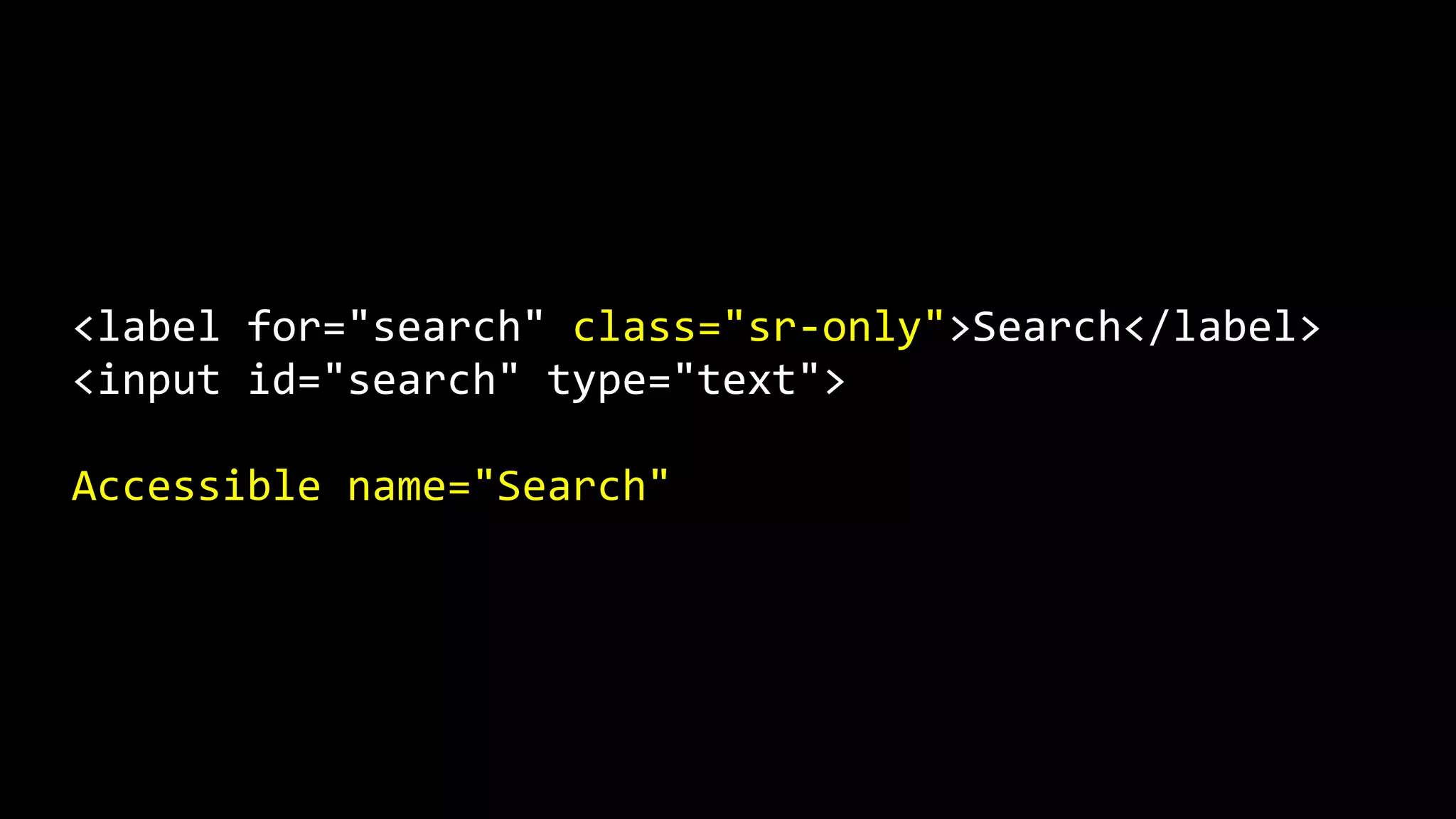

The document discusses the importance of accessible names in web development, explaining how accessibility APIs, the DOM, and the accessibility tree interact to provide meaningful identifiers for UI elements used by assistive technologies. It outlines the process by which browsers compute accessible names based on various attributes like aria-labelledby and aria-label, as well as the best practices for ensuring that all accessible objects have meaningful names. Ultimately, it emphasizes the need for thoughtful design to enhance the user experience for individuals relying on these technologies.