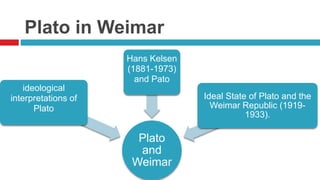

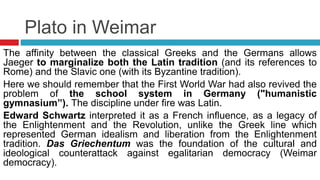

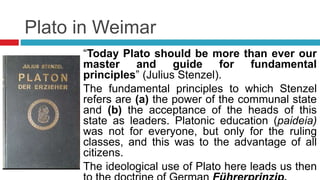

The document explores the connections between Plato's ideal state and the Weimar Republic, emphasizing the challenges faced in creating a perfect government. It highlights various interpretations of Plato's political thought by figures such as Werner Jaeger and Hans Kelsen, contrasting their views on the state and democracy in the historical context of post-World War I Germany. Ultimately, the document posits that both Plato's vision and the Weimar Republic were attempts to establish just political systems that ultimately faced insurmountable obstacles.

![Hans Kelsen’s Plato between

philosophy and law

Plato, The Seventh Letter

[334c] All this has been said by way of counsel to Dion's

friends and relatives. And one piece of counsel I add, as I

repeat now for the third time to you in the third place the

same counsel as before, and the same doctrine.

Neither Sicily, nor yet any other State - such is my

doctrine - should be enslaved to human despots

but rather to laws; …

[337c] And when the laws have been laid down, then

everything depends on the following

condition. On the one hand, if the victors prove

themselves subservient to the laws more than [337d] the

vanquished, then all things will abound in safety and

happiness, and all evils will be avoided; but should it

prove otherwise, neither I nor anyone else should be

called in to take part in helping the man who refuses to

For Kelsen (1881-1973), in

fact, the Grundnorm, by

definition, does not derive

from other laws. It is a

paradigm in the sense that it

can indicate a particular

written constitution and so

makes its interpretation the

responsibility of the jurist but

also gives the responsibility

for decision-making to

politicians. It’s possible to

identify the sovereignty](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/uvlxba1-150619204030-lva1-app6891/85/Plato-in-Weimar-Plato-s-Ideal-State-and-the-Weimar-Republic-The-impossibility-of-Creating-The-Perfect-State-16-320.jpg)