This document provides an overview of the key concepts and principles of utilitarianism. It discusses:

1) The fundamental tenets of utilitarianism including that morality is about producing the greatest good for the greatest number and maximizing overall well-being.

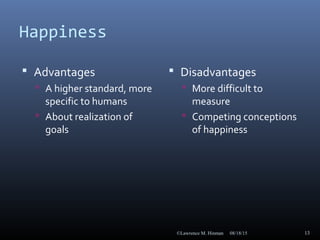

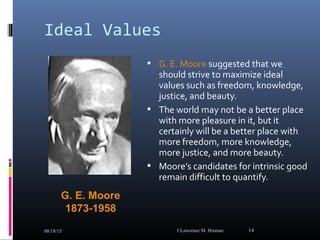

2) The history of utilitarian thought including different views on what constitutes intrinsic value (pleasure, happiness, ideals, preferences).

3) How utilitarians employ a "calculus" approach to weigh the costs and benefits of actions to determine the option with the highest utility.

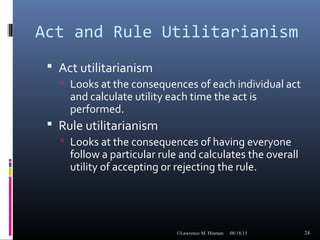

4) The difference between act and rule utilitarianism and how they assess individual actions and rules.

5) Common criticisms of utilitarianism related to