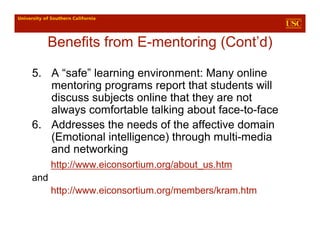

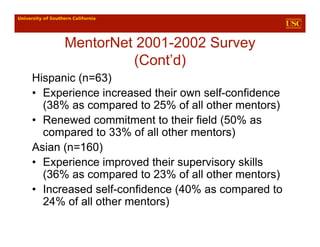

E-mentoring involves using electronic communications to develop mentoring relationships between a more experienced mentor and a lesser skilled protégé regardless of their physical location. Two examples of structured e-mentoring programs described are the International Telementor Program, which facilitates online mentoring relationships between students and professionals worldwide, and MentorNet, a nonprofit that matches women studying engineering with industry professionals through email-based mentoring. Benefits of e-mentoring include providing guidance, support and access to professional networks to help protégés succeed while allowing for flexible communication independent of time and location.