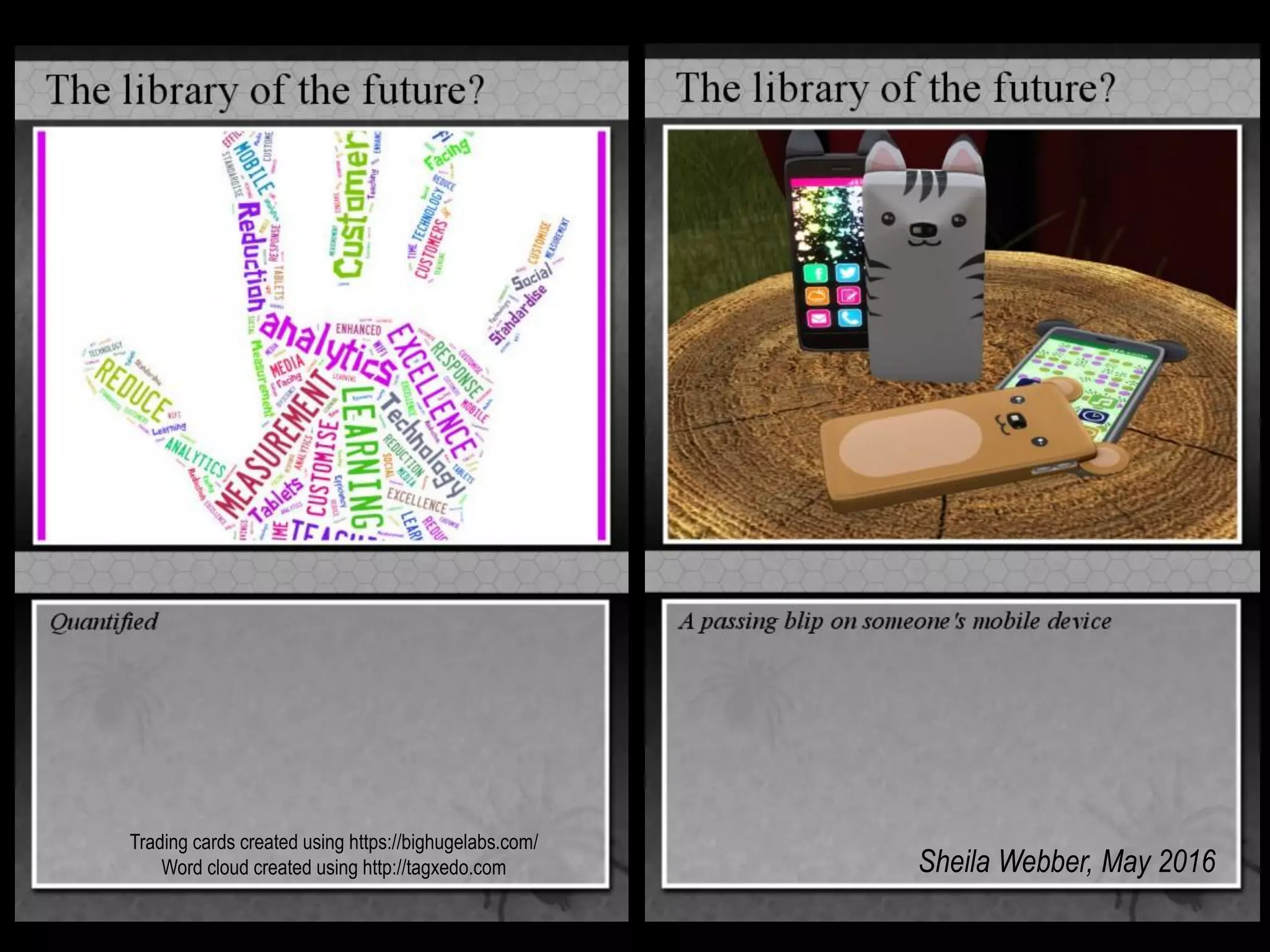

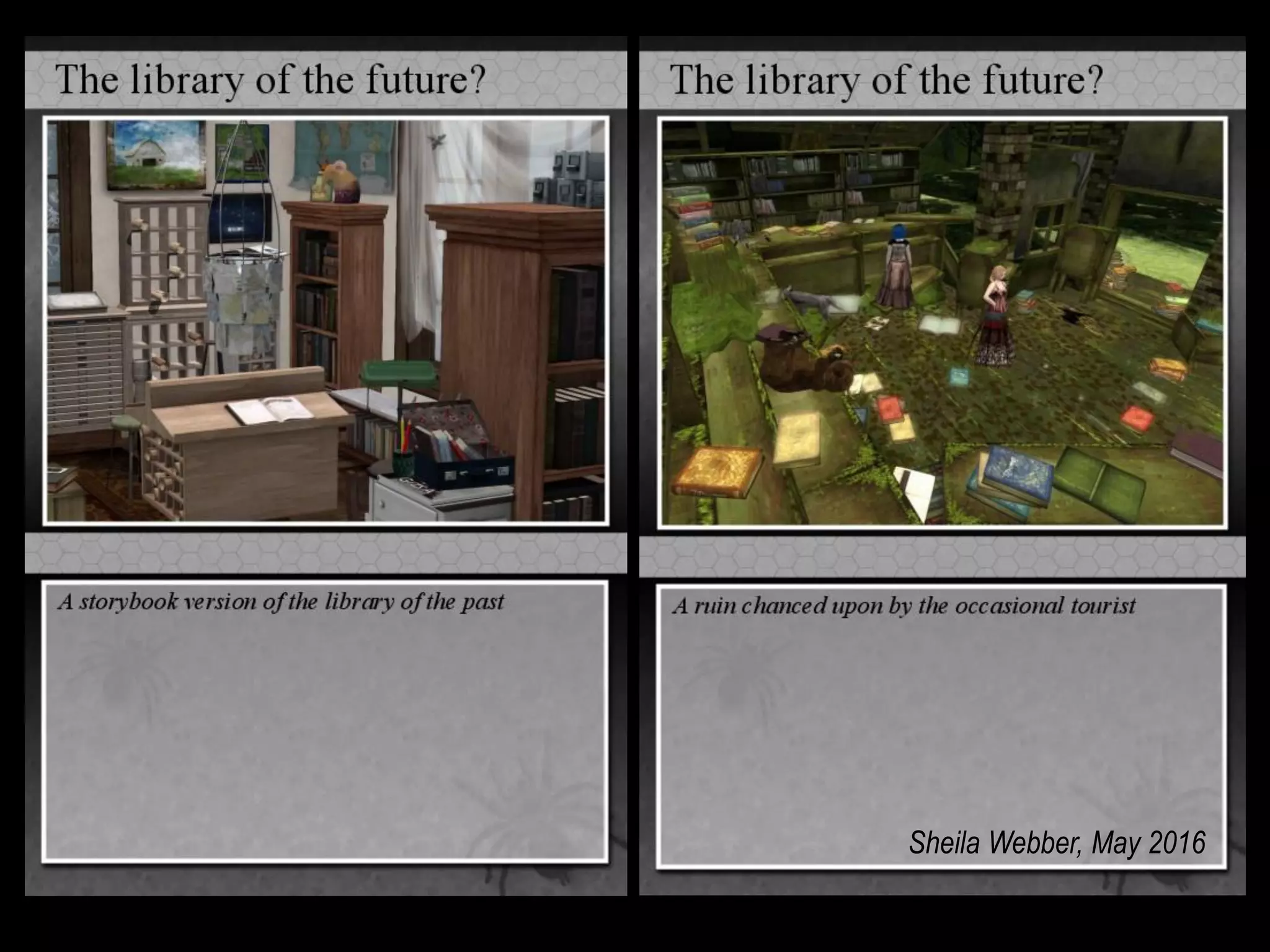

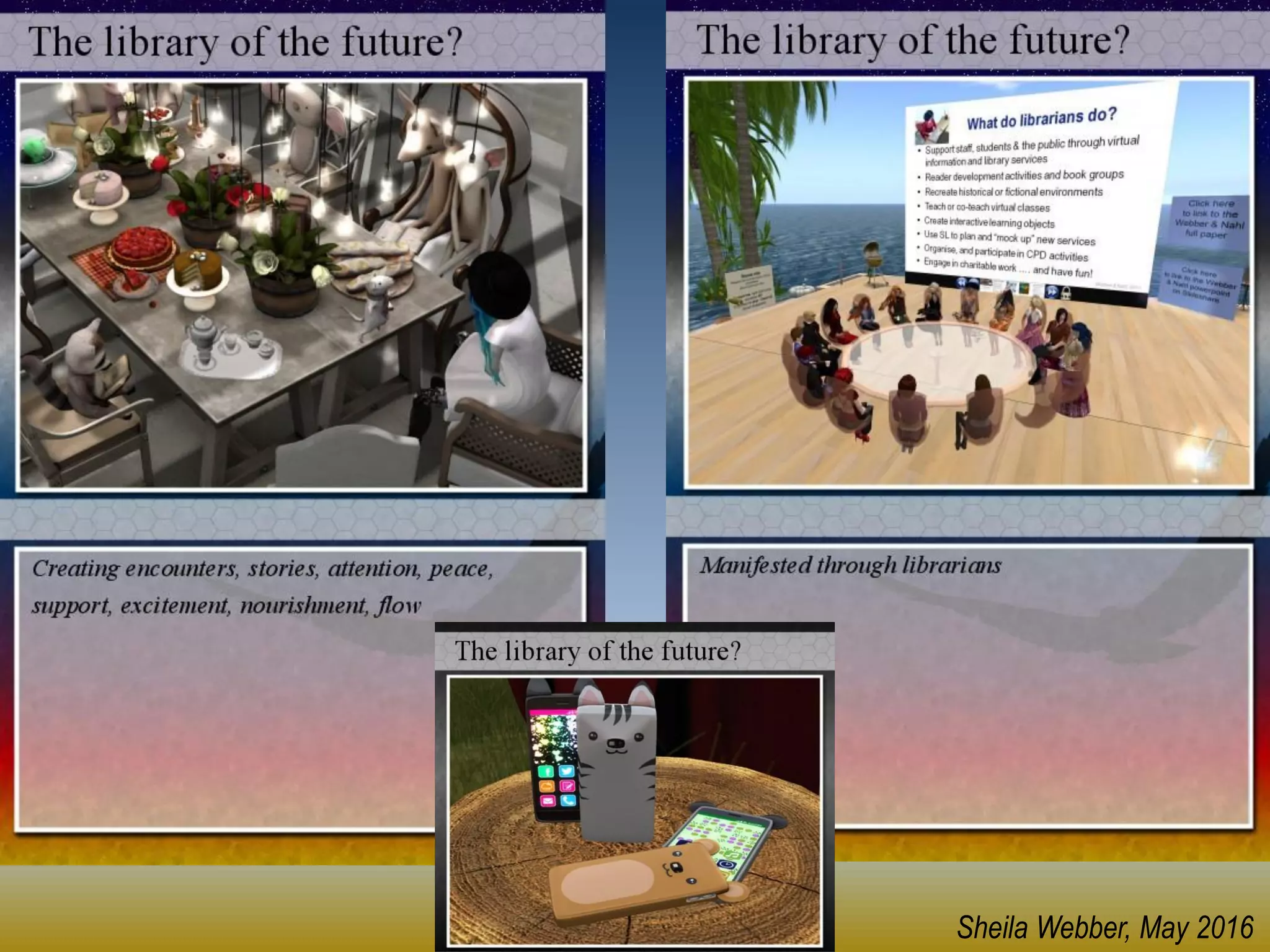

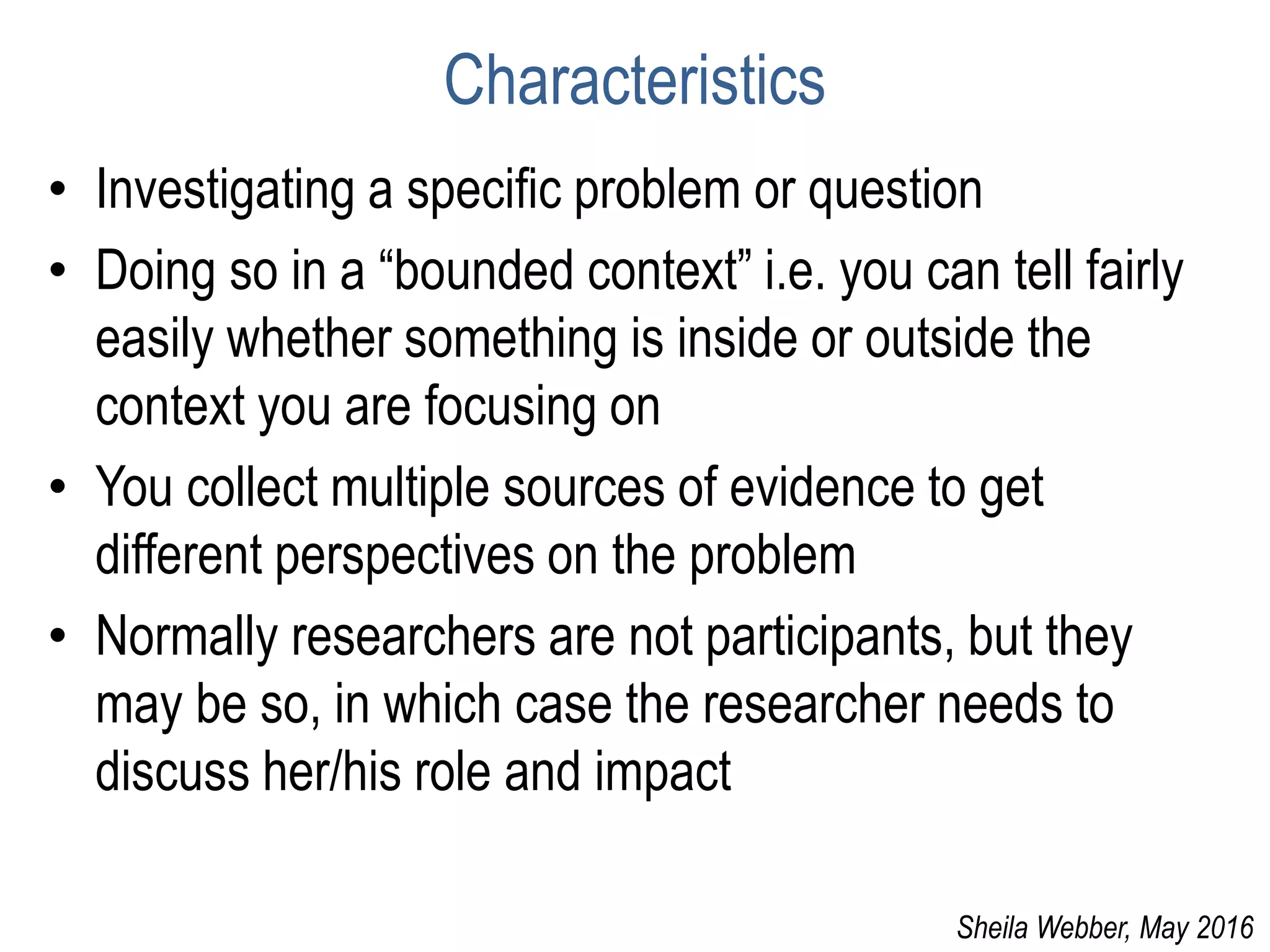

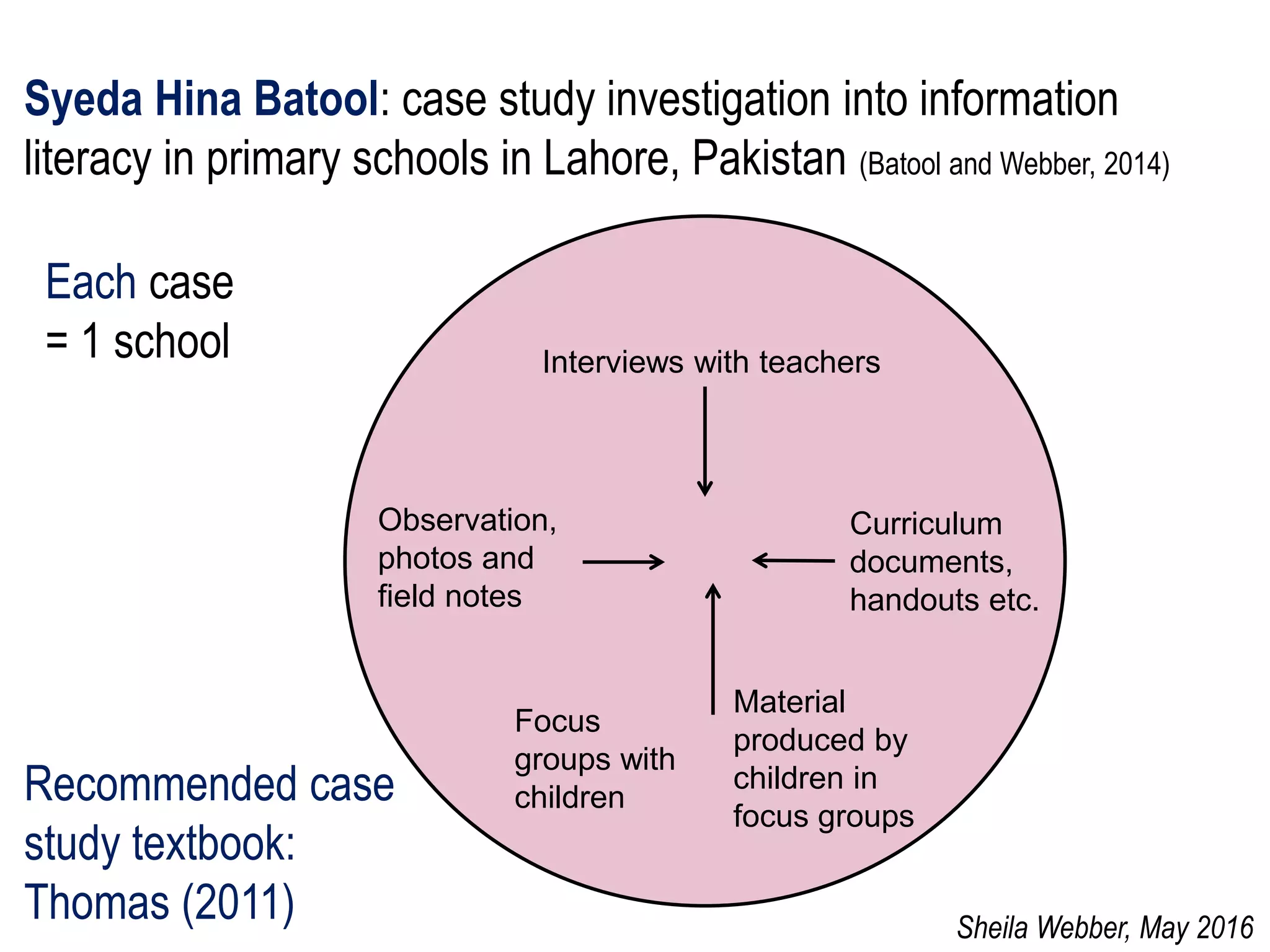

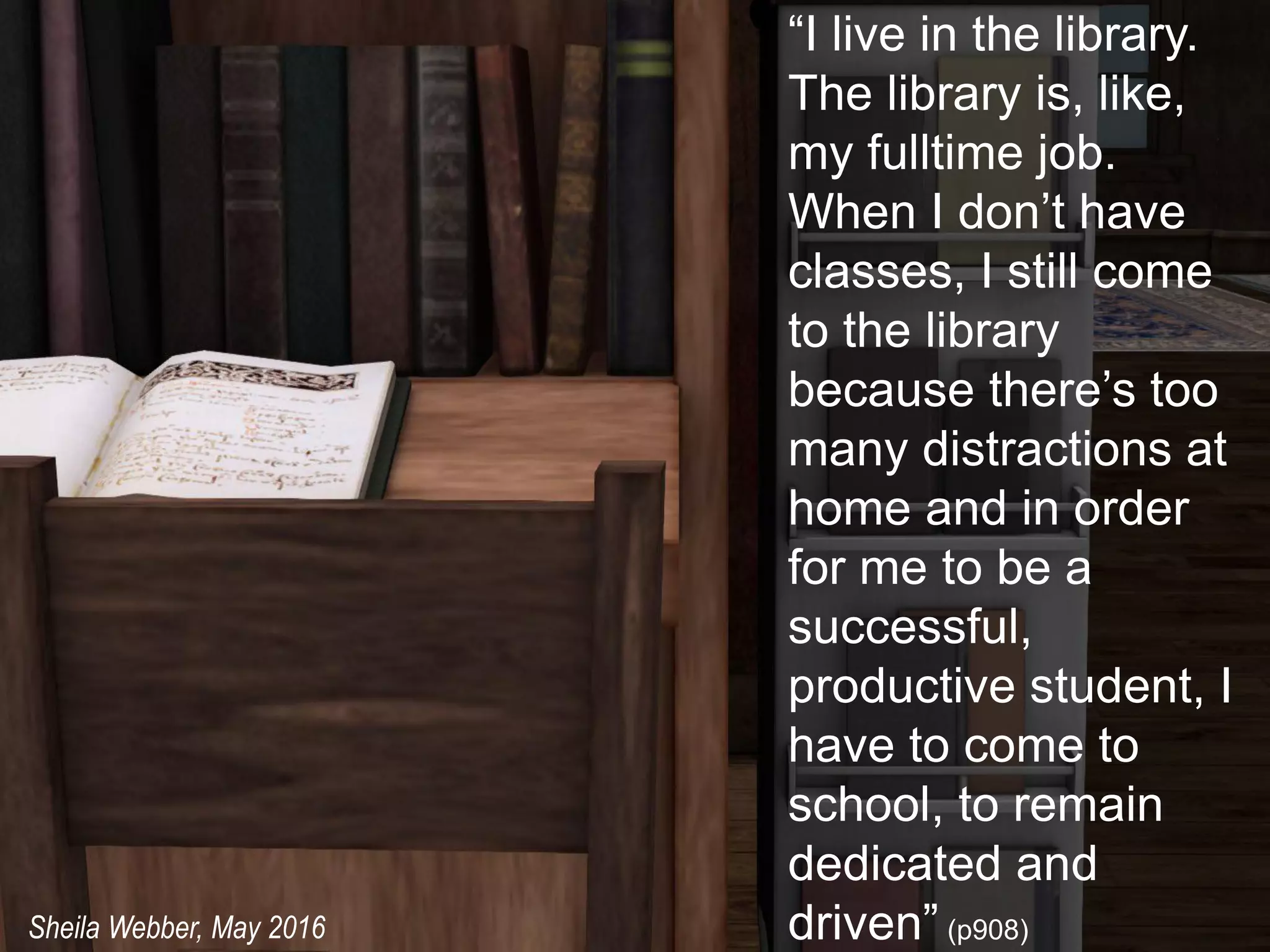

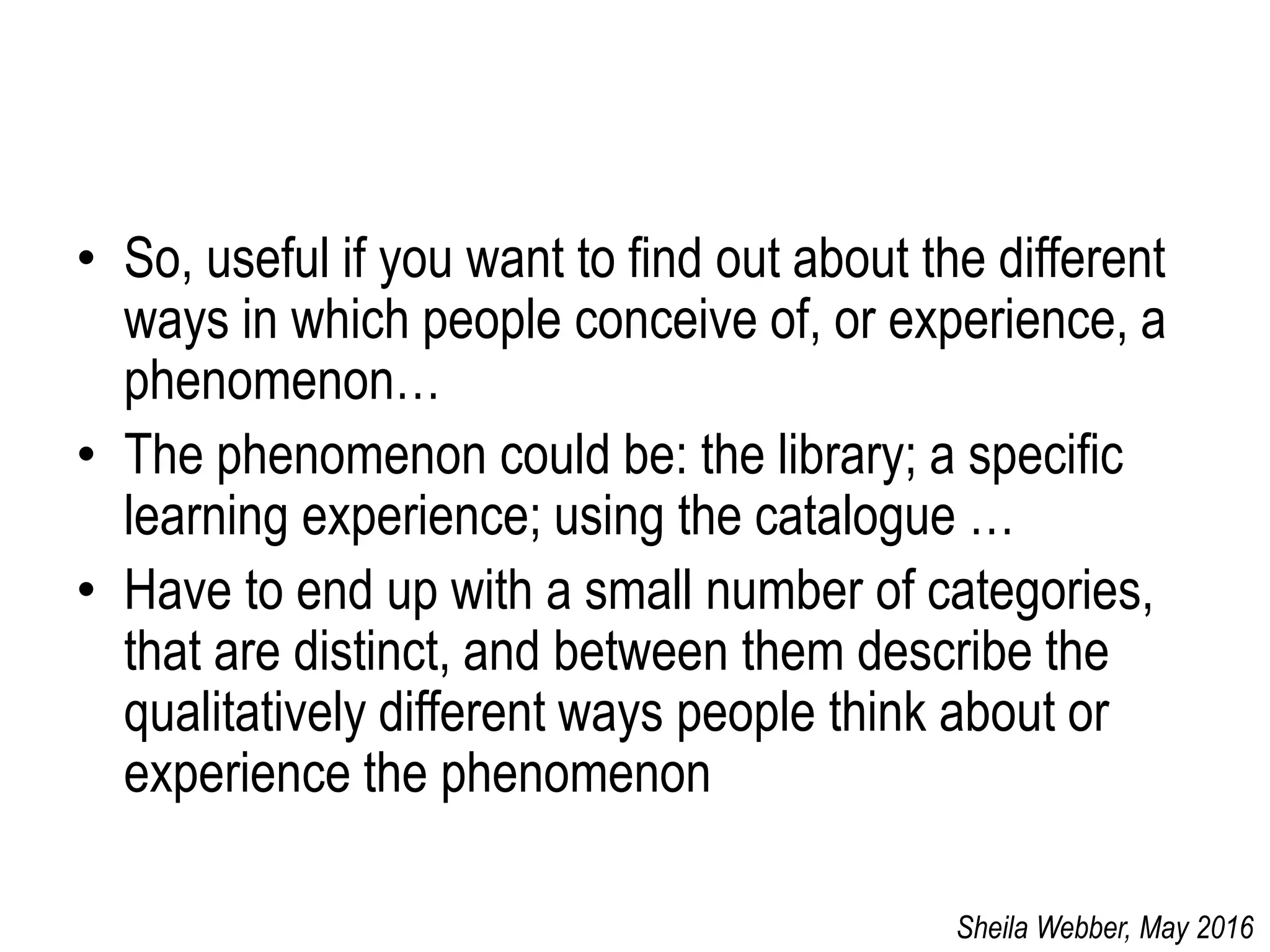

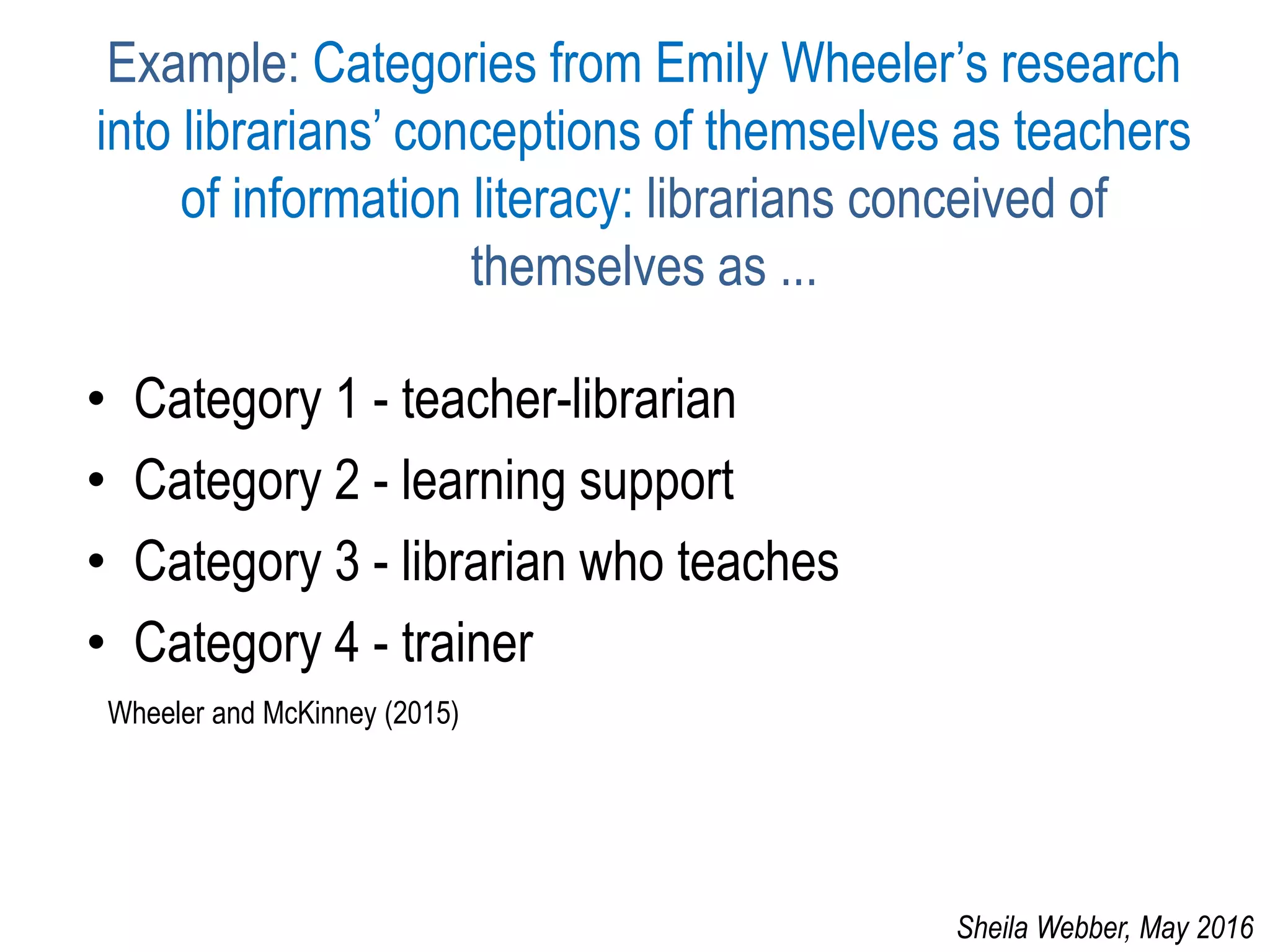

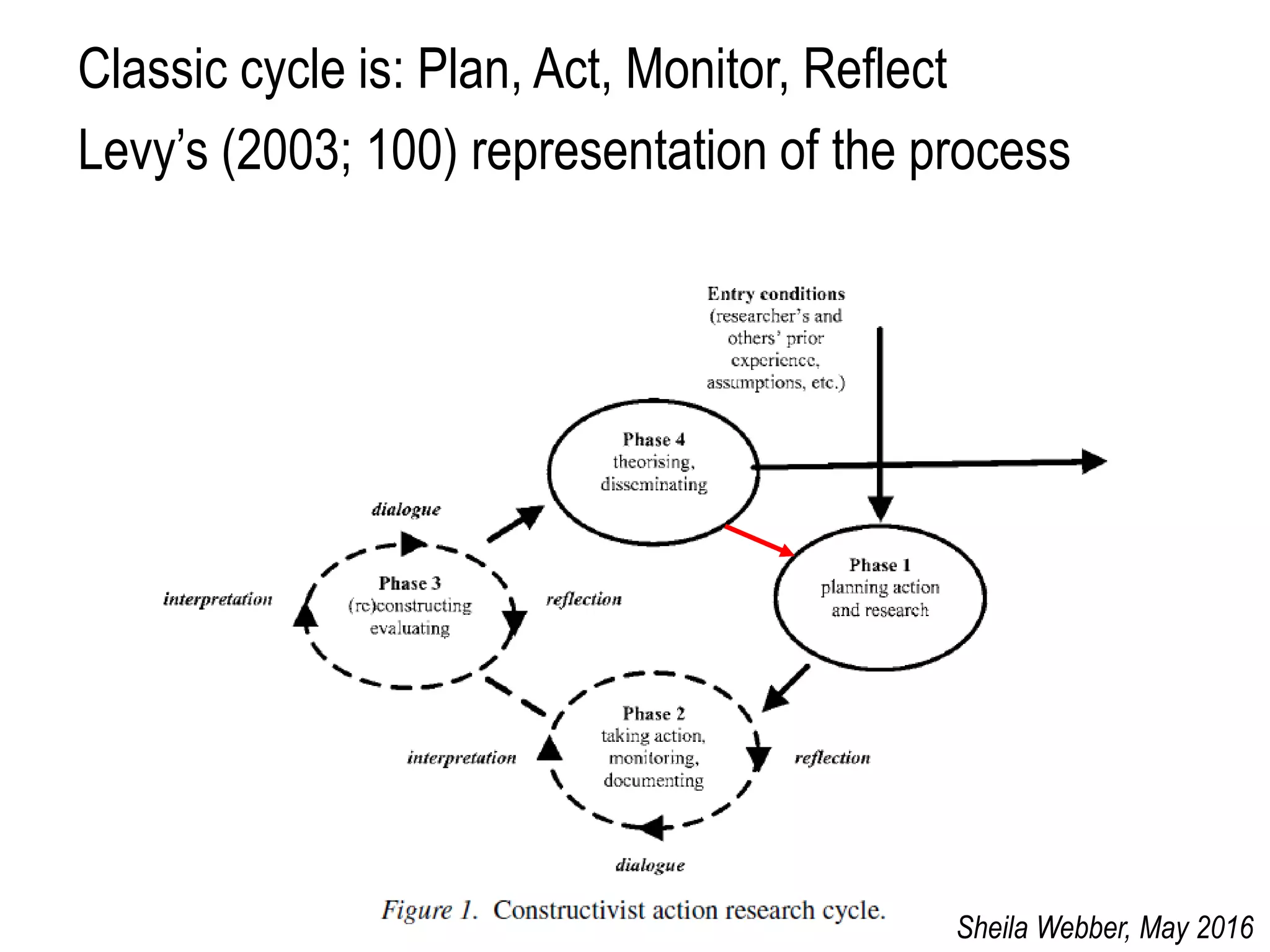

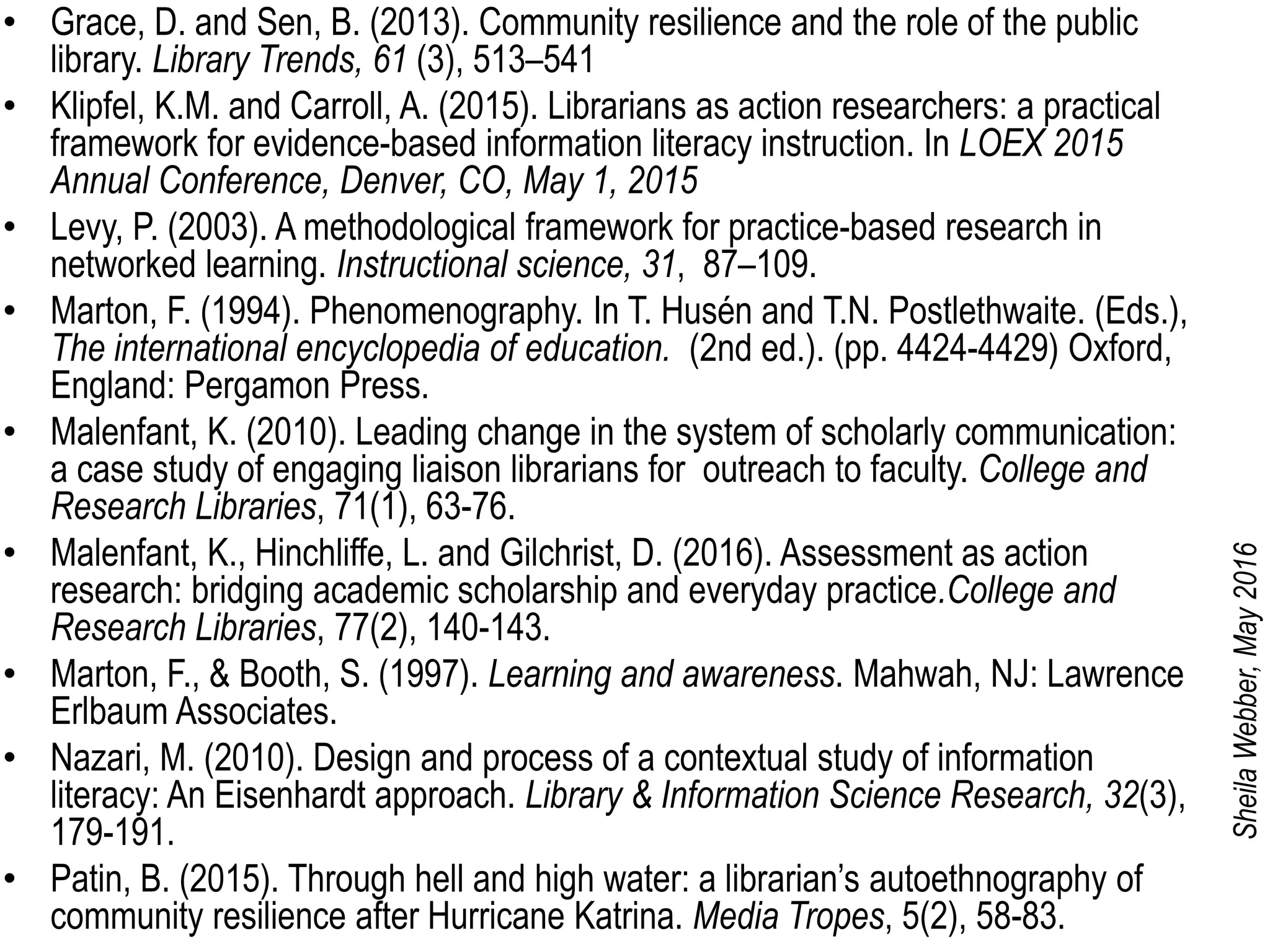

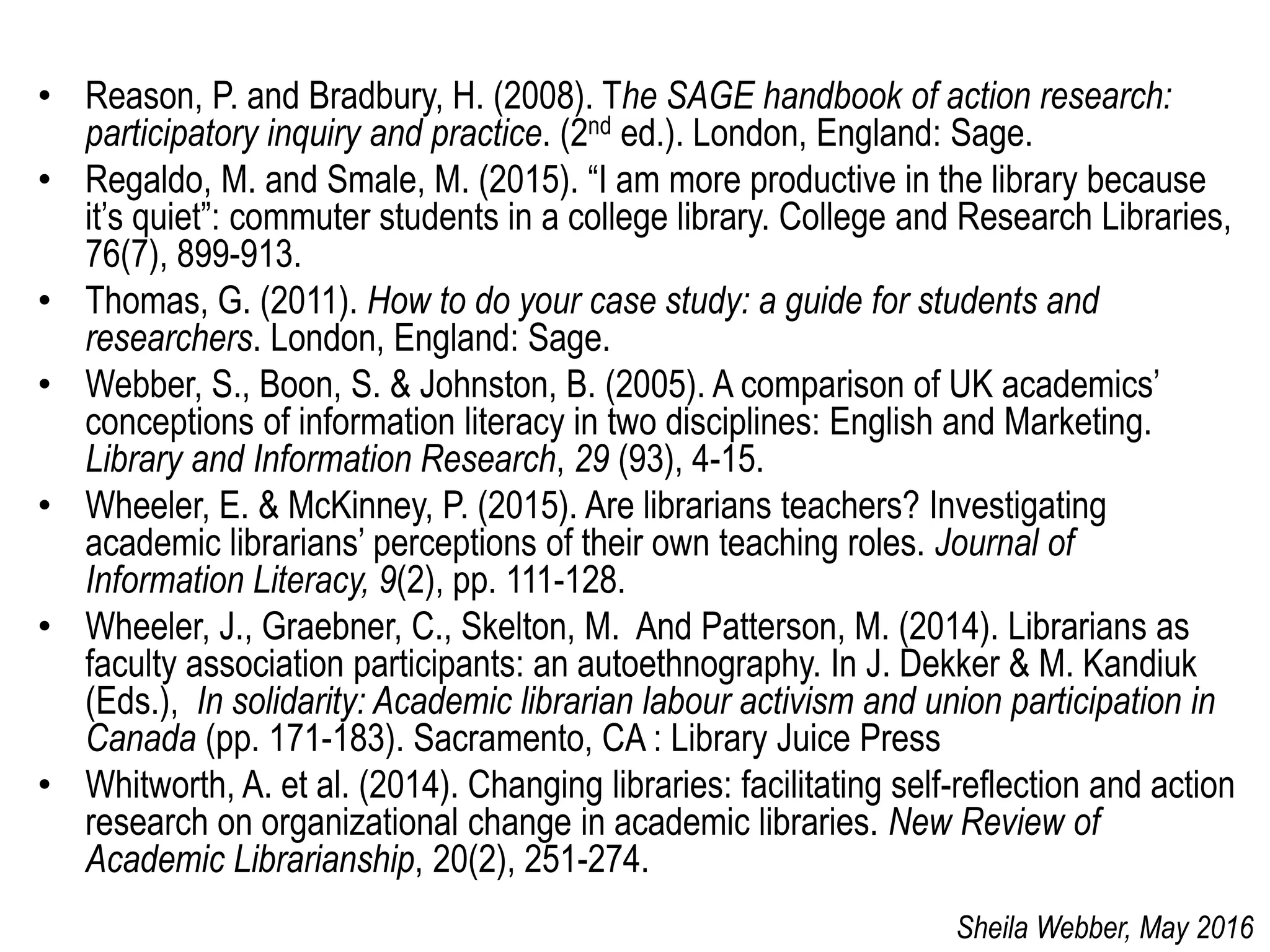

The document presents insights from Sheila Webber's plenary talk at the QQML conference, focusing on trends and challenges facing academic libraries. It emphasizes the importance of qualitative research approaches in understanding users' experiences and the library's role in their lives, advocating for methods like case studies, ethnography, and autoethnography. Additionally, it highlights the need for libraries to adapt to social and technological changes while addressing users' specific needs and embracing evidence-based practices.