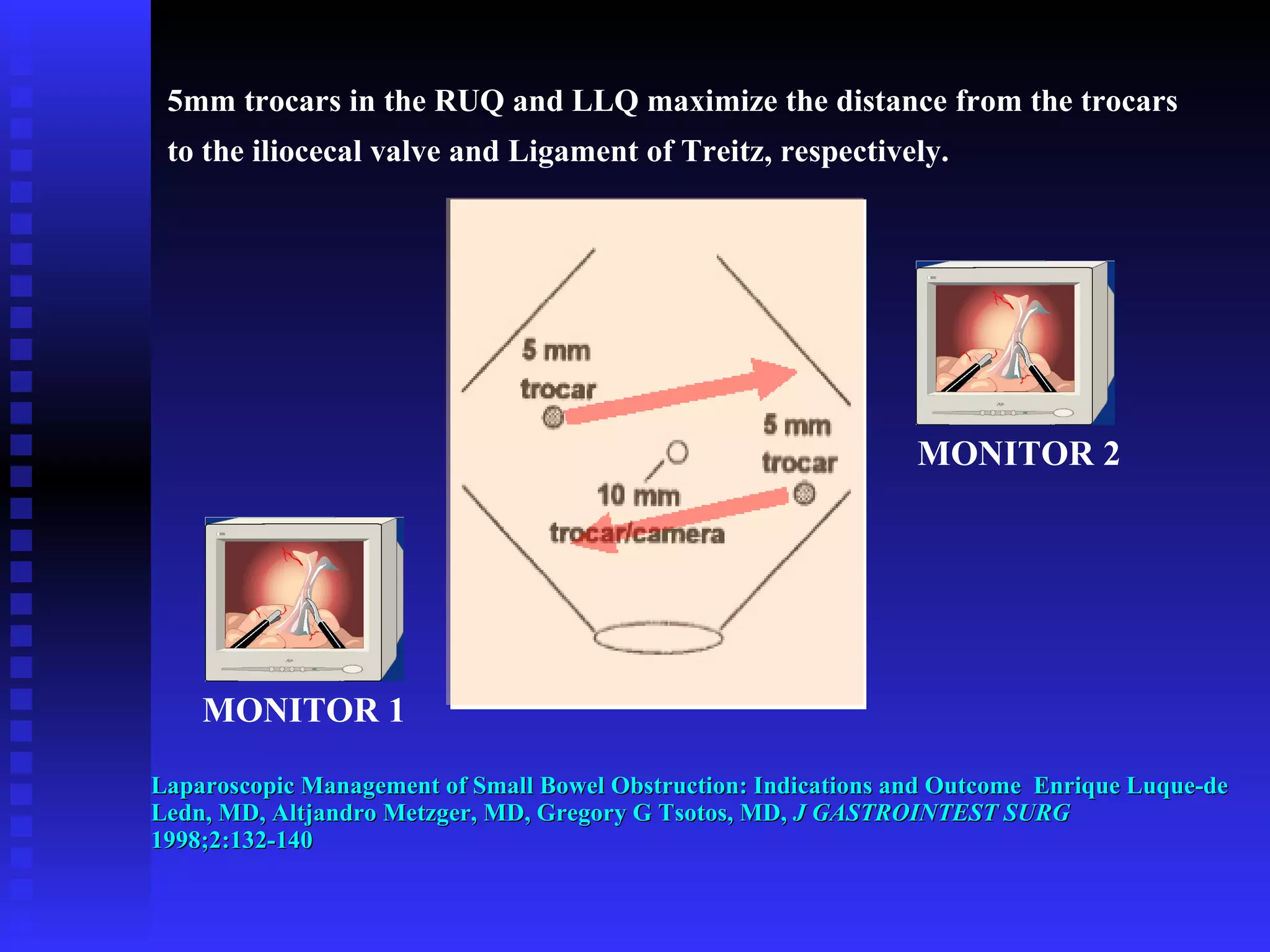

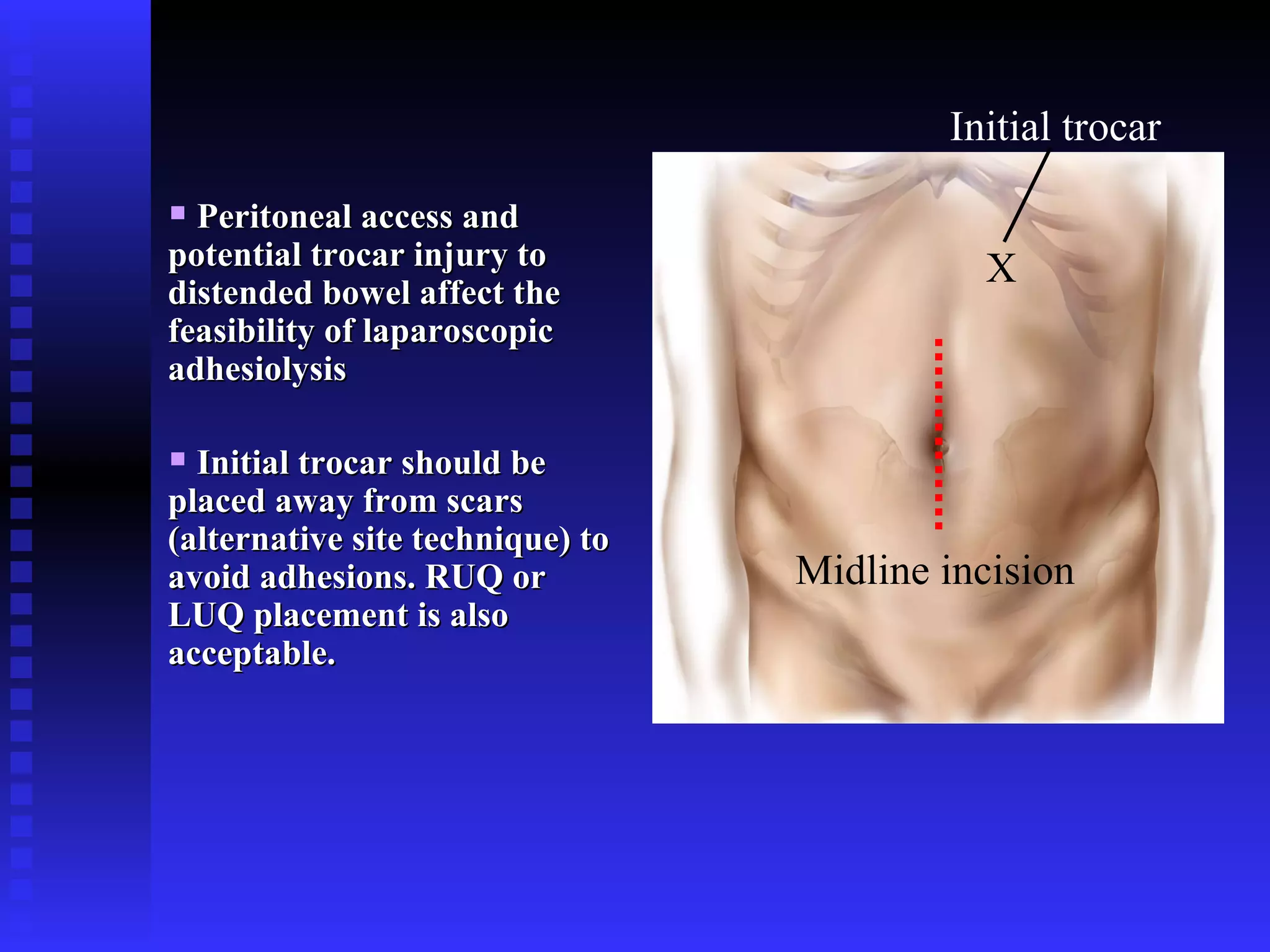

The document provides information on laparoscopic dissection of adhesions. It discusses the historical perspectives on adhesions, adhesion pathophysiology, prevention of adhesion formation, complications related to adhesions, results of laparoscopic adhesiolysis for small bowel obstruction, operating room set up, laparoscopic management indications and outcomes, laparoscopic approach, peritoneal access and potential trocar injury, optical access trocars, and recommended tools for adhesiolysis.