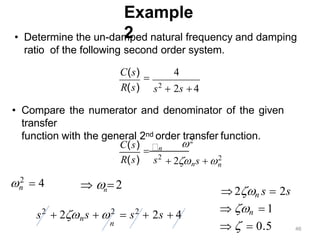

Here are the key steps:

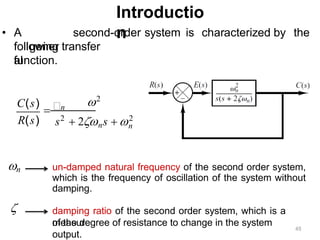

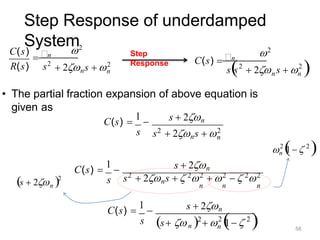

1) Identify the second order system transfer function:

C(s)/R(s) = 4/(s^2 + 2s + 4)

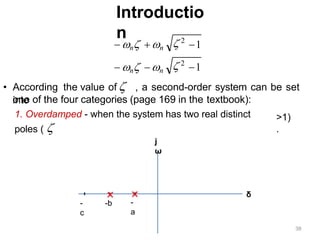

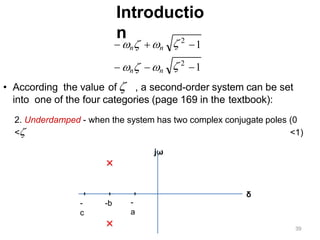

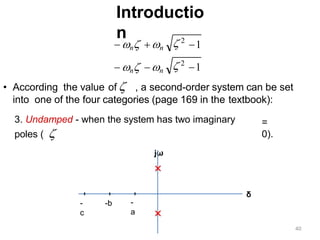

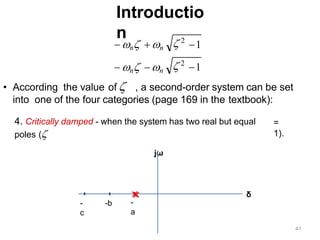

2) Compare to the general second order system transfer function:

C(s)/R(s) = ωn^2/(s^2 + 2ζωns + ωn^2)

3) Equate coefficients:

ωn^2 = 4

2ζωn = 2

ωn = 2

ζ = 1

Therefore, the un-damped natural frequency (ωn) is 2 rad/s and the damping ratio (ζ) is 1.

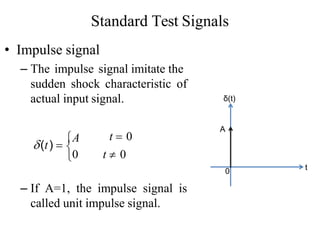

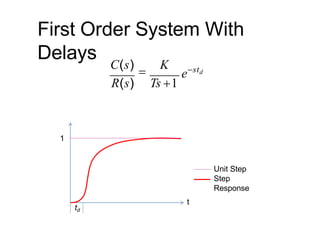

![First Order System With

Delays

[10(t 2) 10e1/3(t2)

]u(t 2)

4

2

10 10

L1

[es

F(s)] f (t )u(t )

s(3s1)

10

C(s)

R(s) 3s1

C(s)

10

e2s

1

)e ]

s s 1/ 3

L [( 2s

e2s

0 5 10 15

0

6

8

10

Step Response

Time (sec)

td2s

T3s

K10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/timedomainanalysis-230720145530-e33f599f/85/time-domain-analysis-pptx-33-320.jpg)