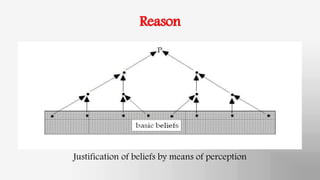

This document discusses human thought and reason. It explores the nature of thoughts and how rational cognition allows humans to have great intellectual achievements. Rational thought is not different in kind between routine tasks like basic math problems and more complex achievements in science and art. Thoughts can be composed of ideas or concepts, and language allows the communication of thoughts between individuals and the formation of society. Reasoning is an ongoing process of building arguments from basic beliefs through perception.