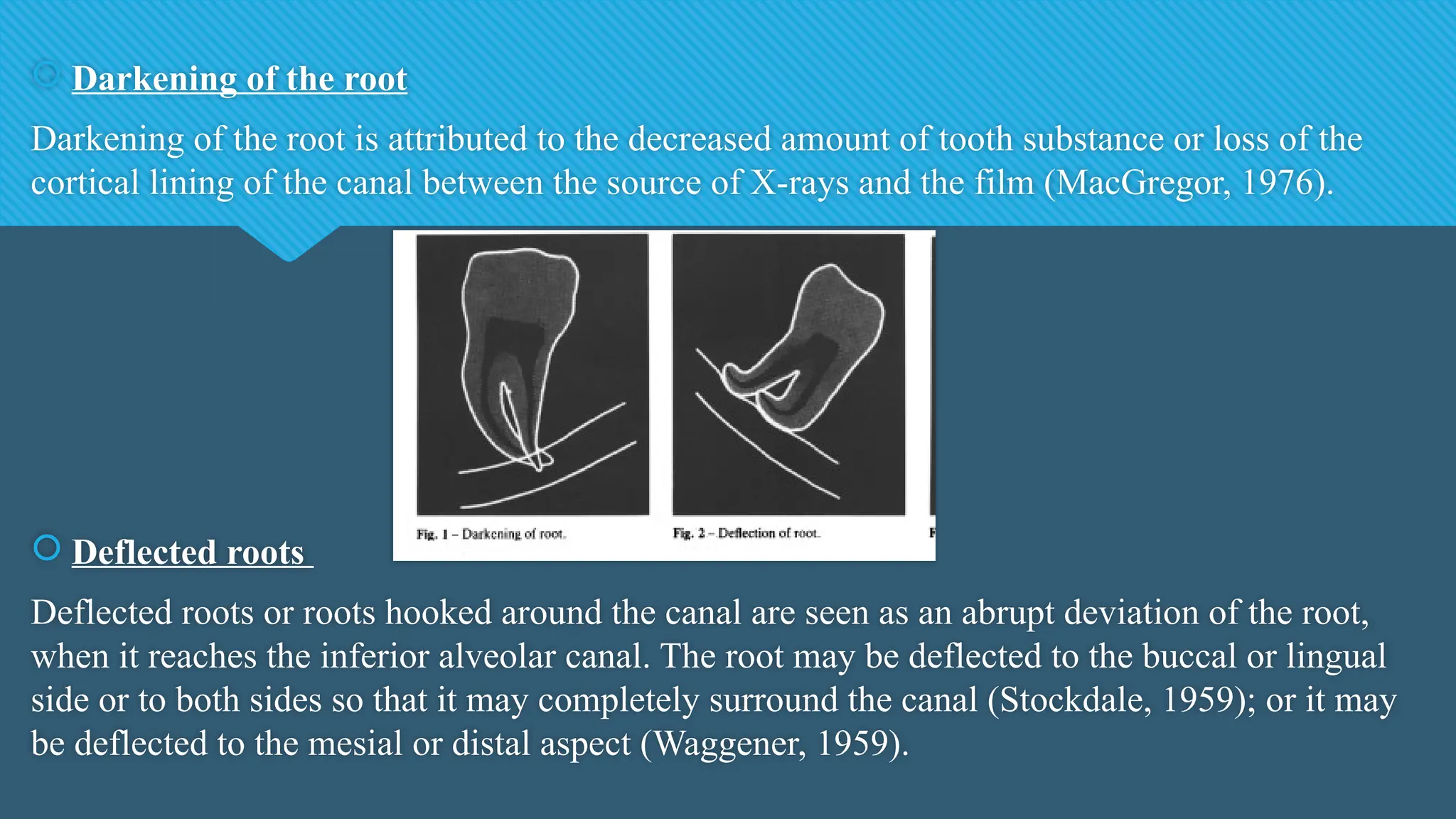

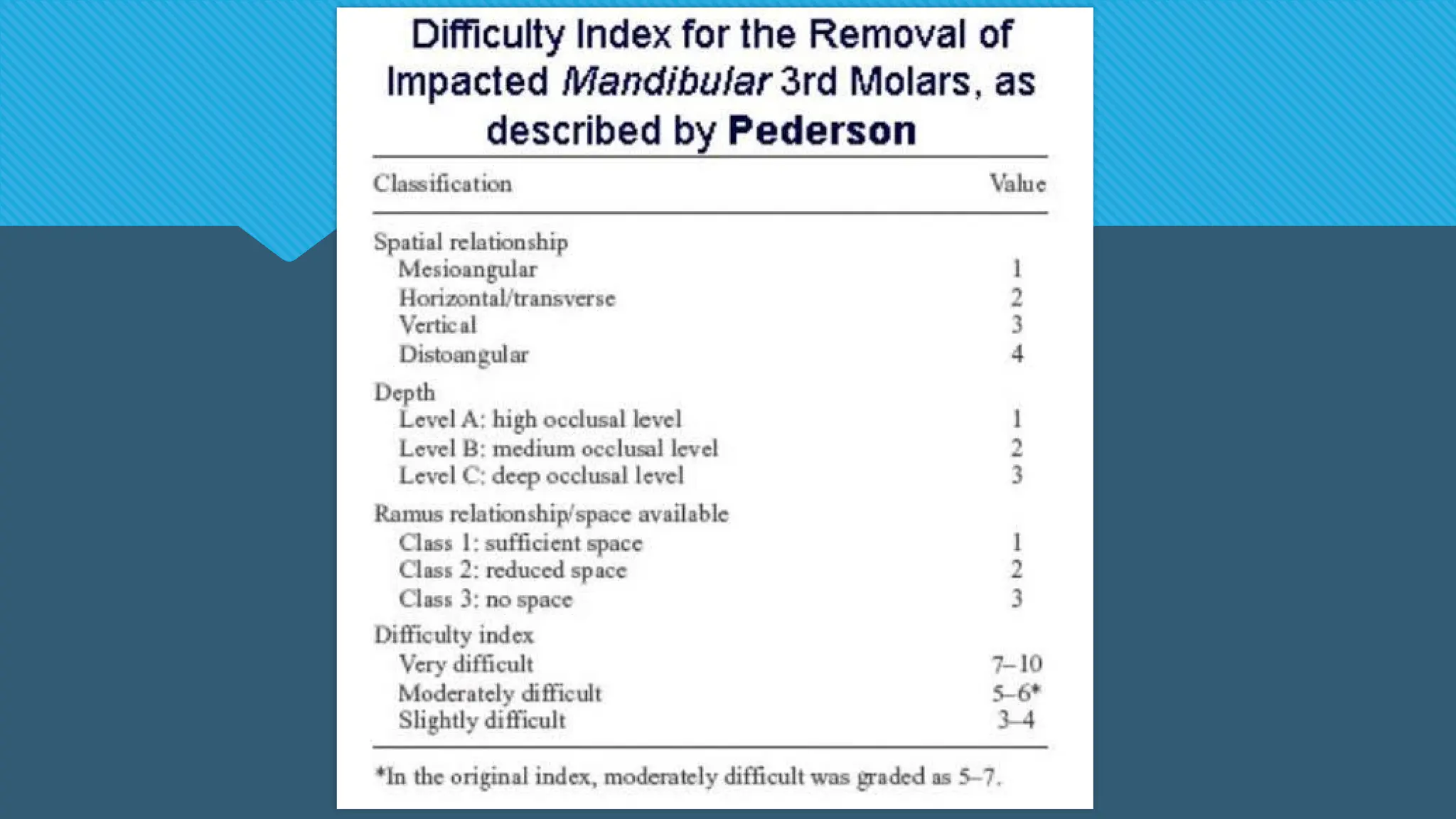

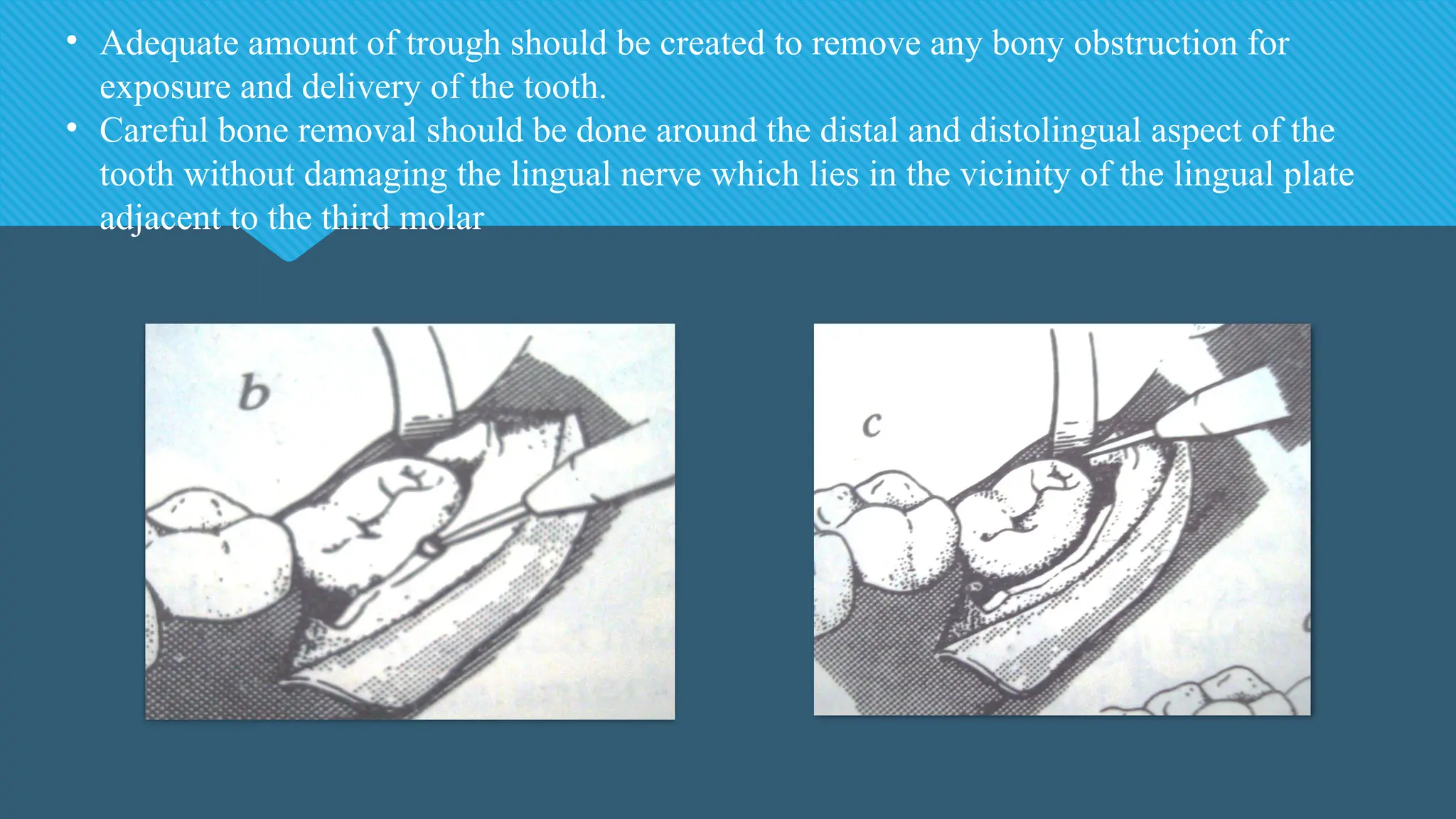

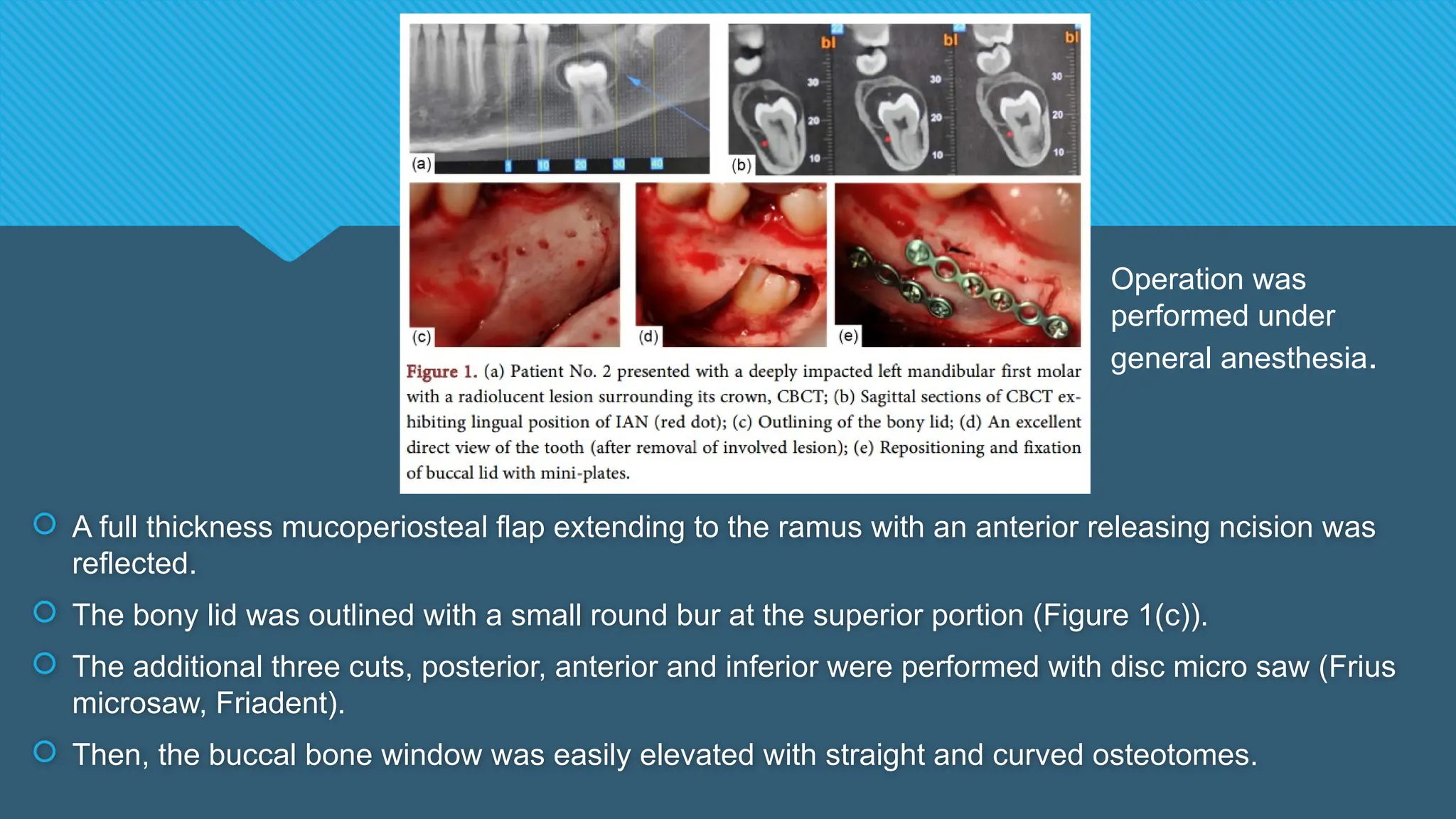

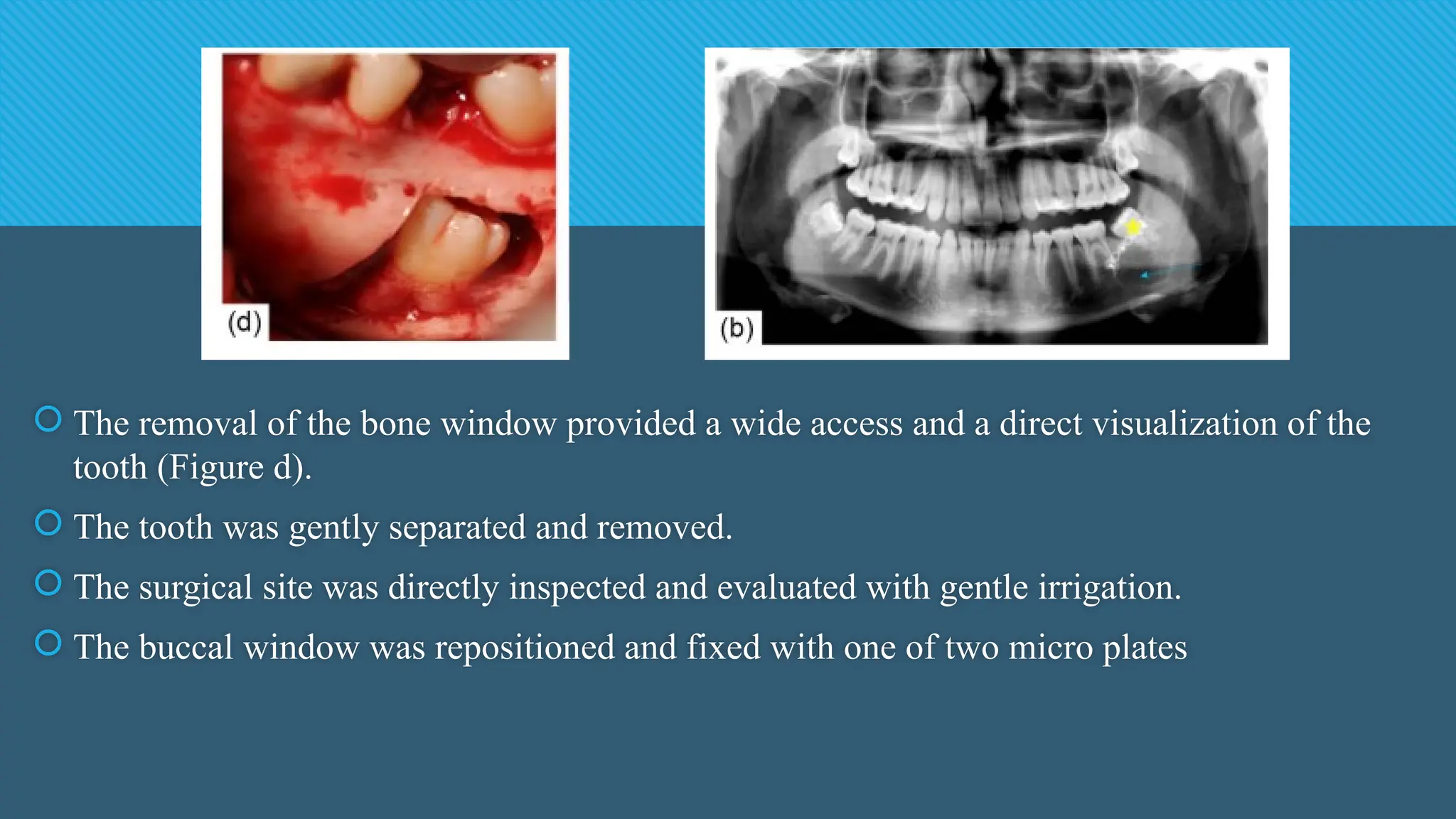

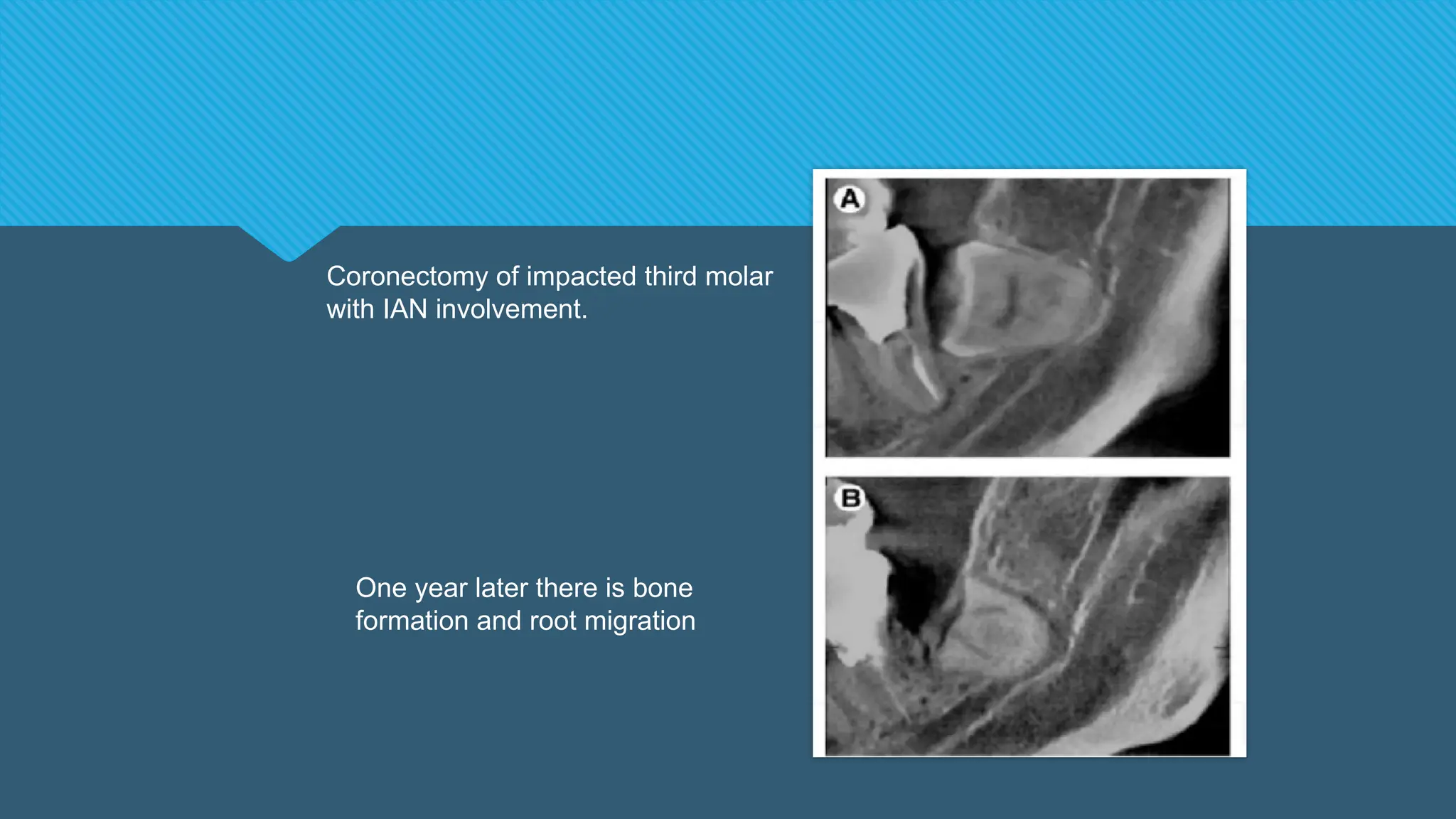

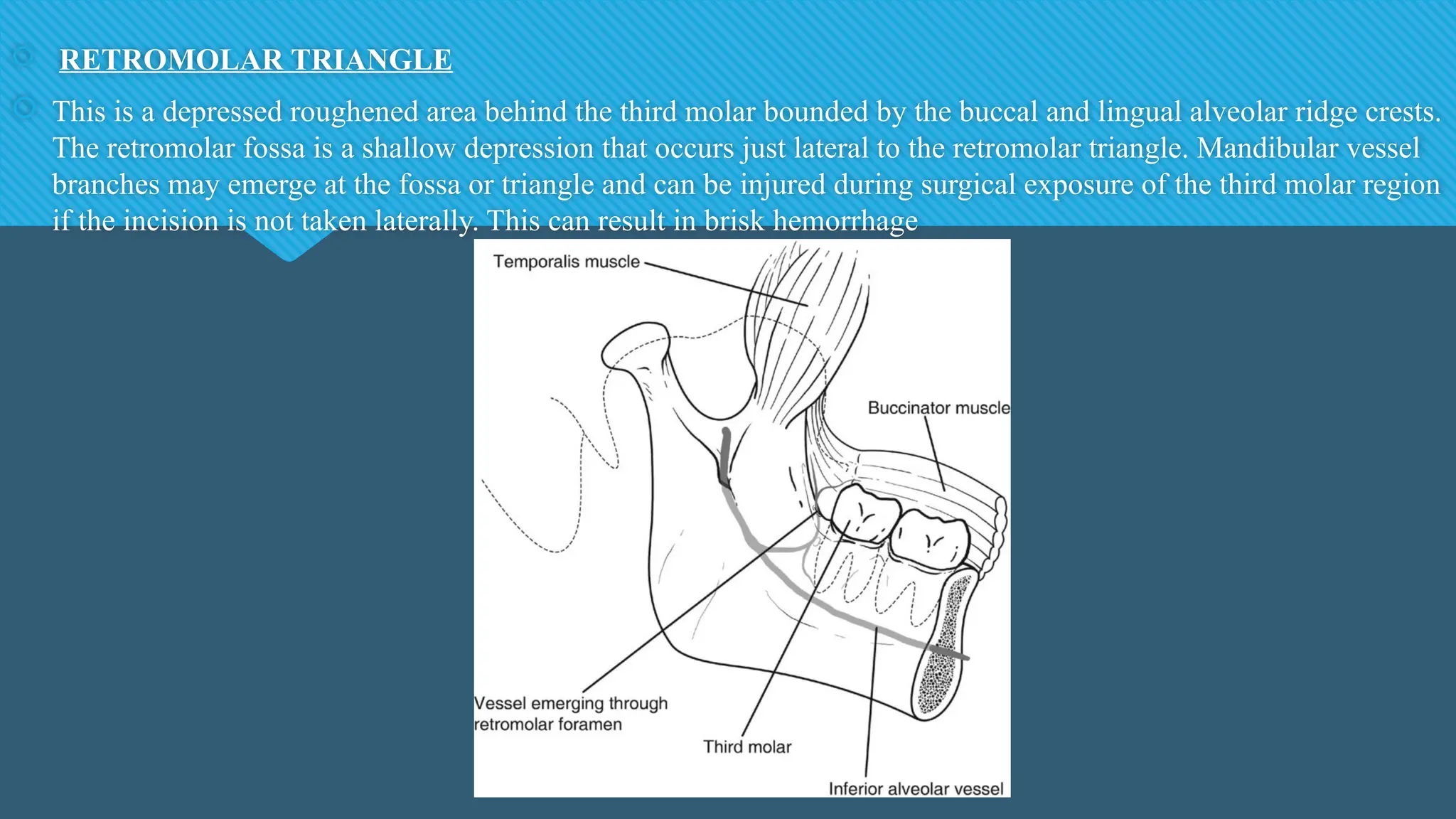

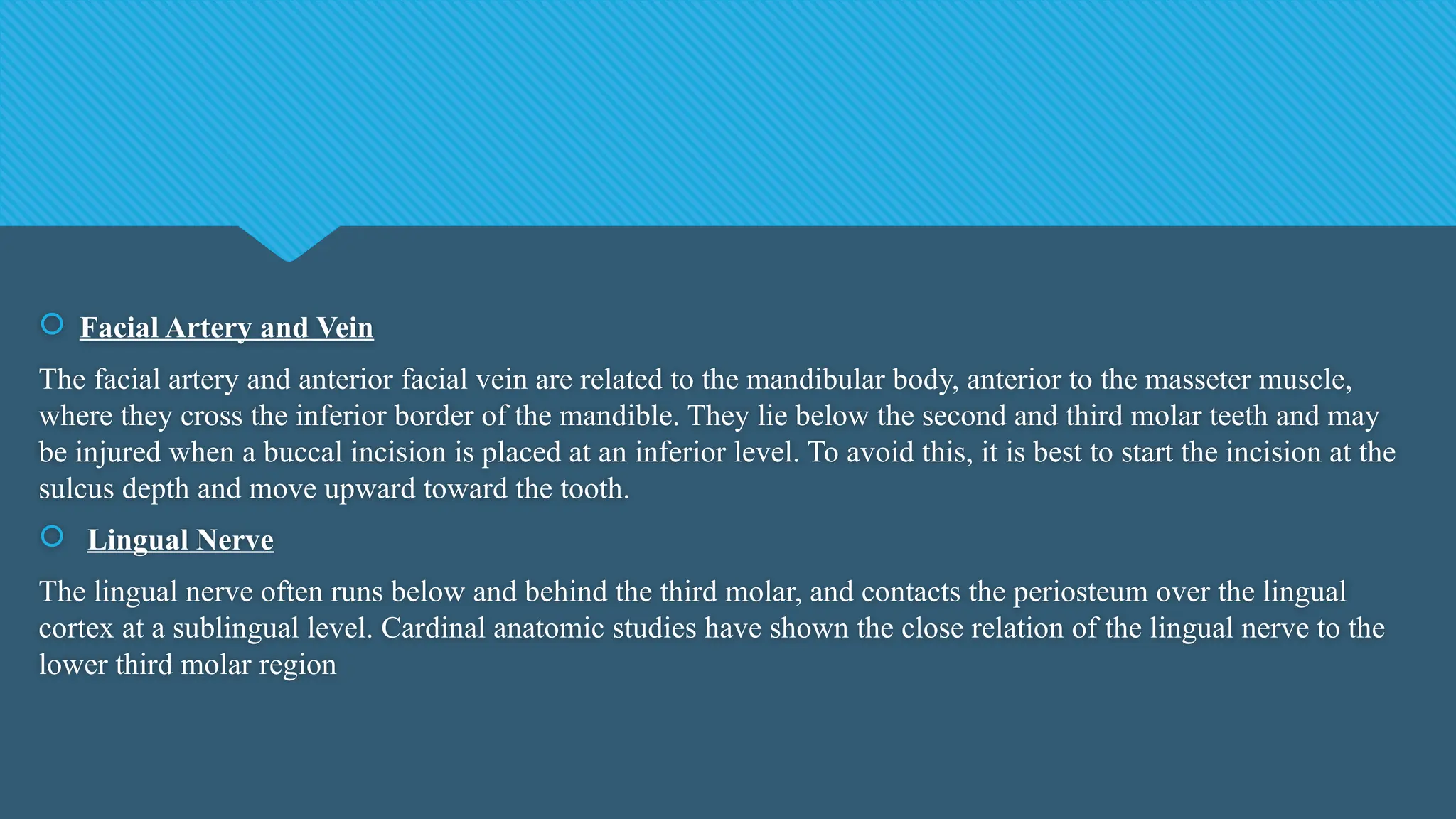

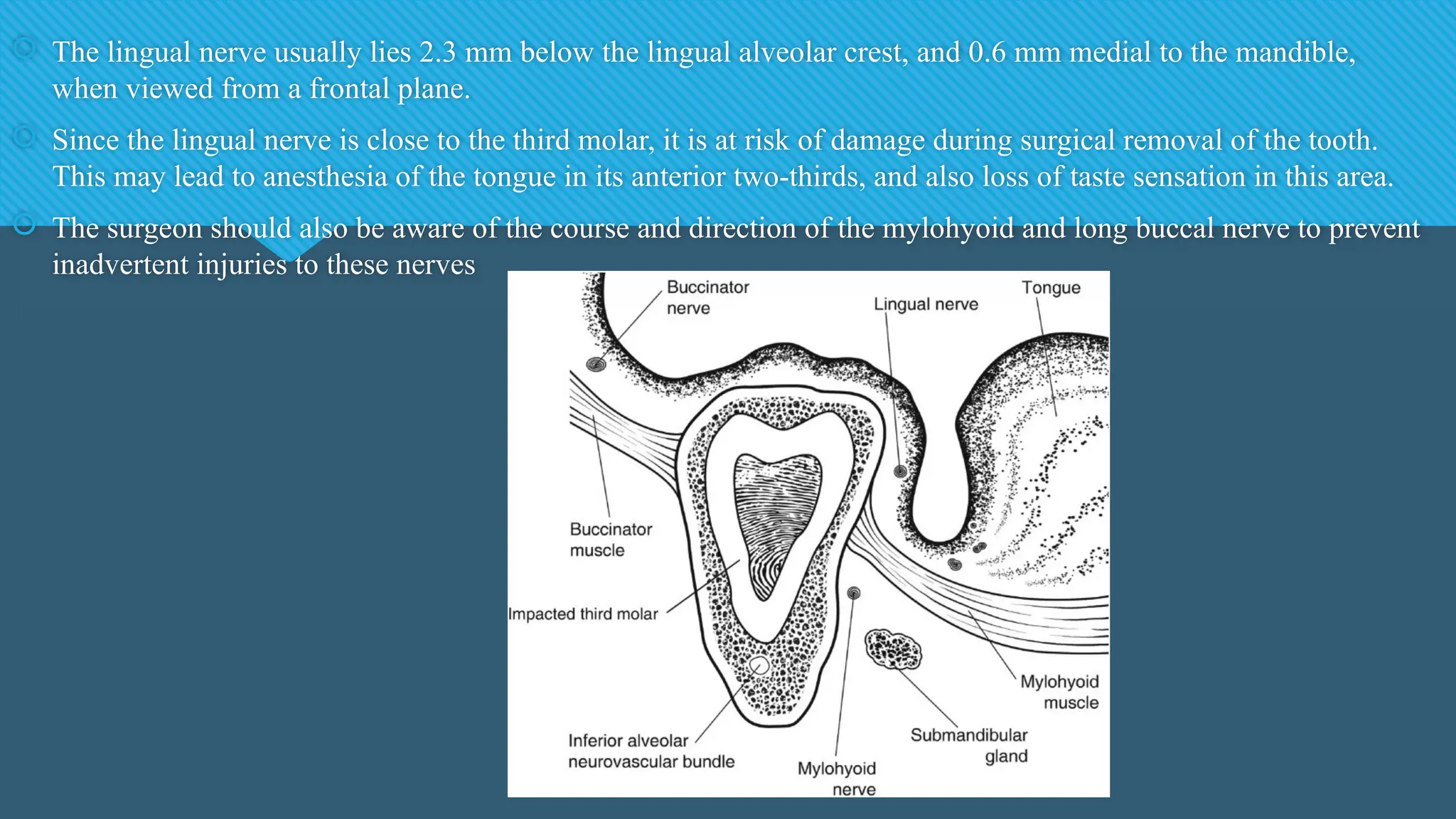

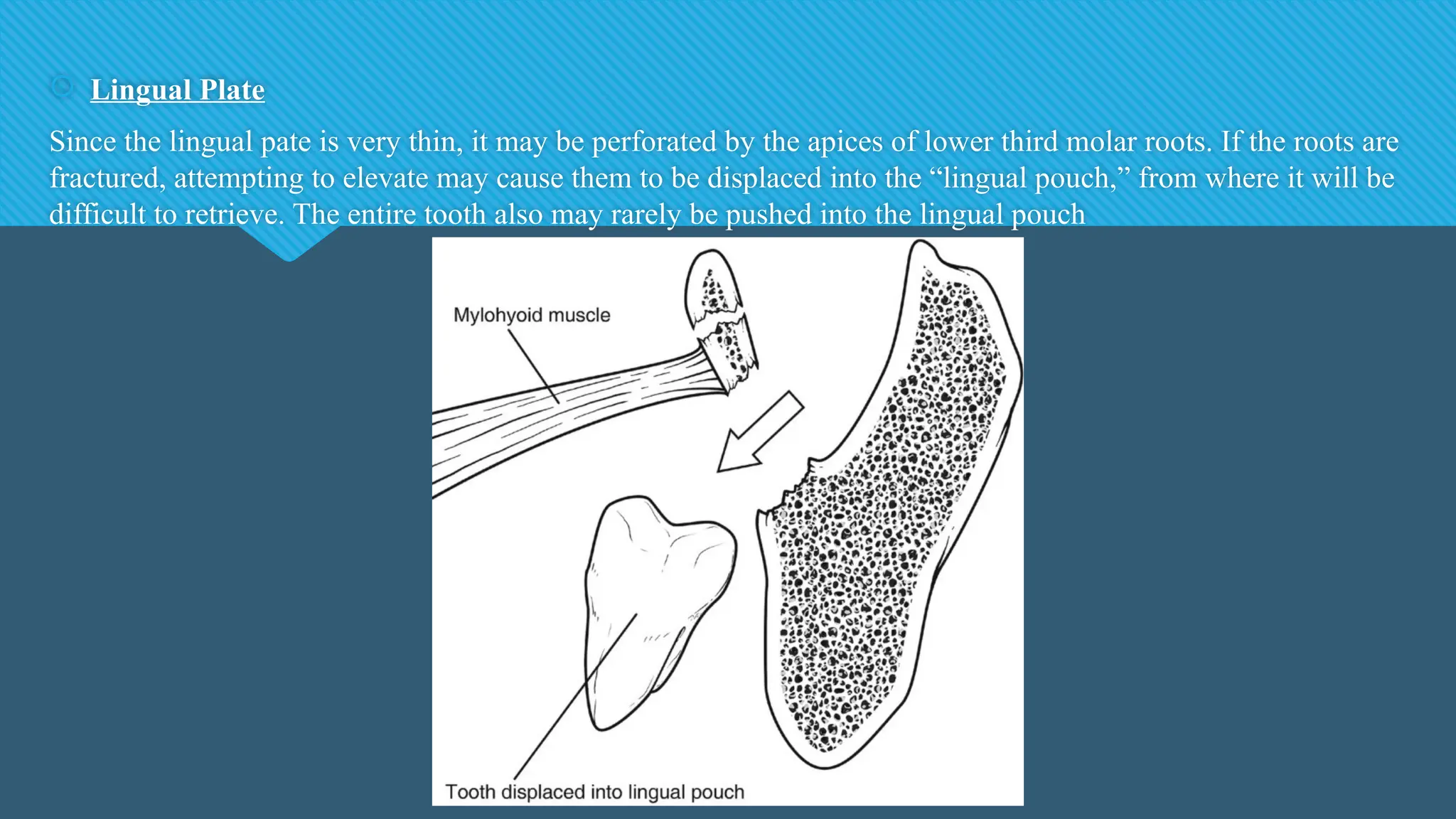

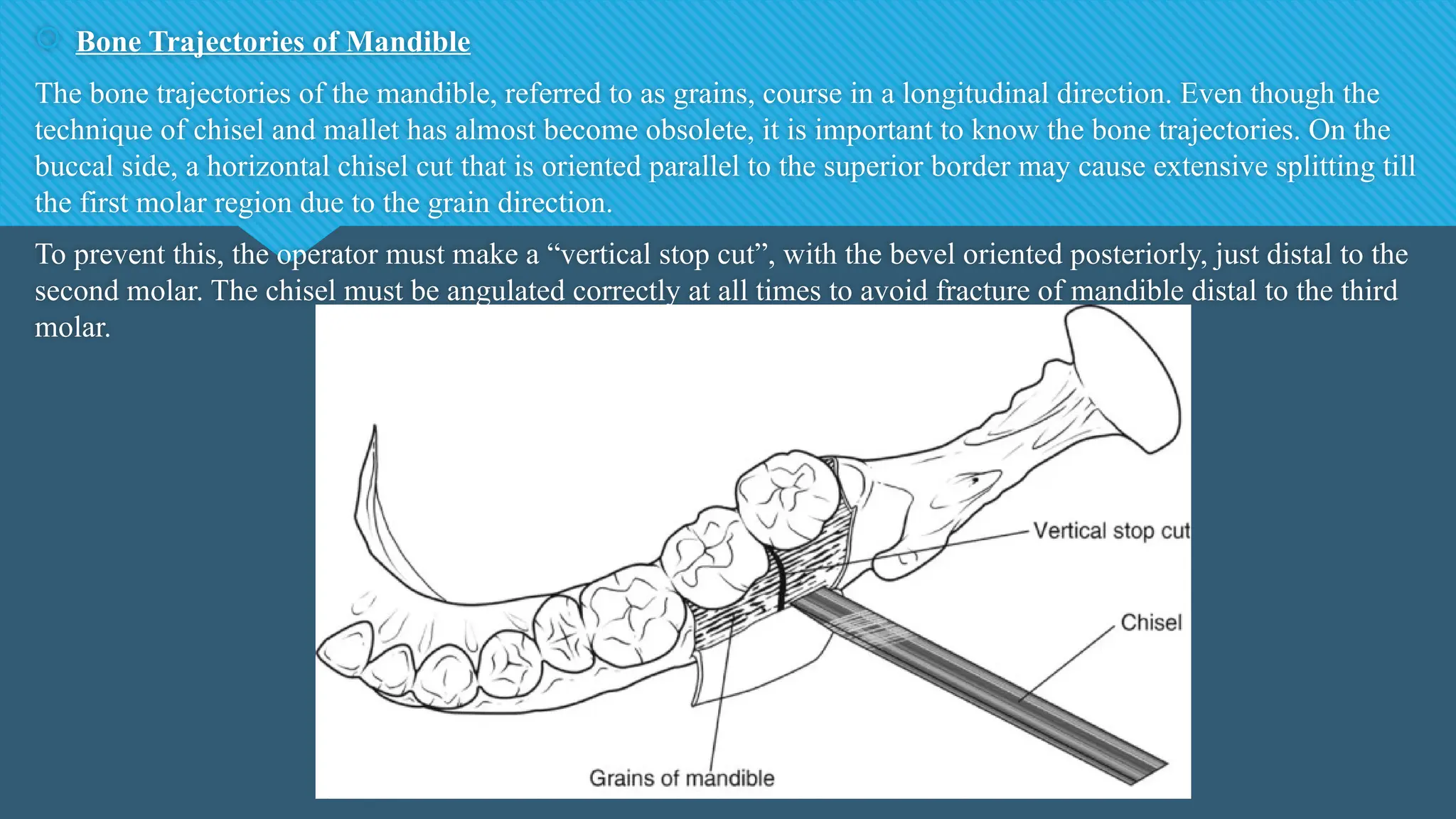

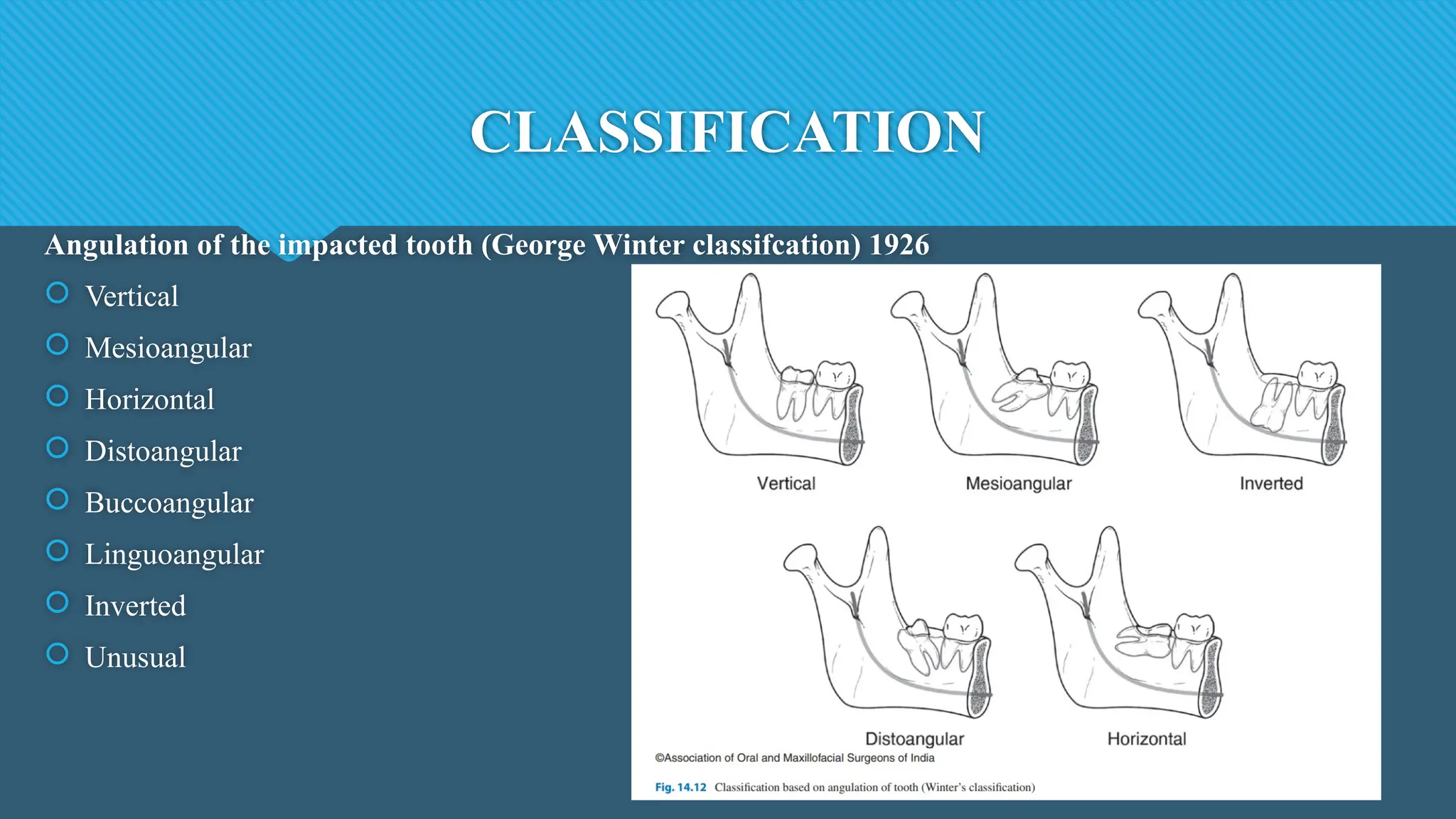

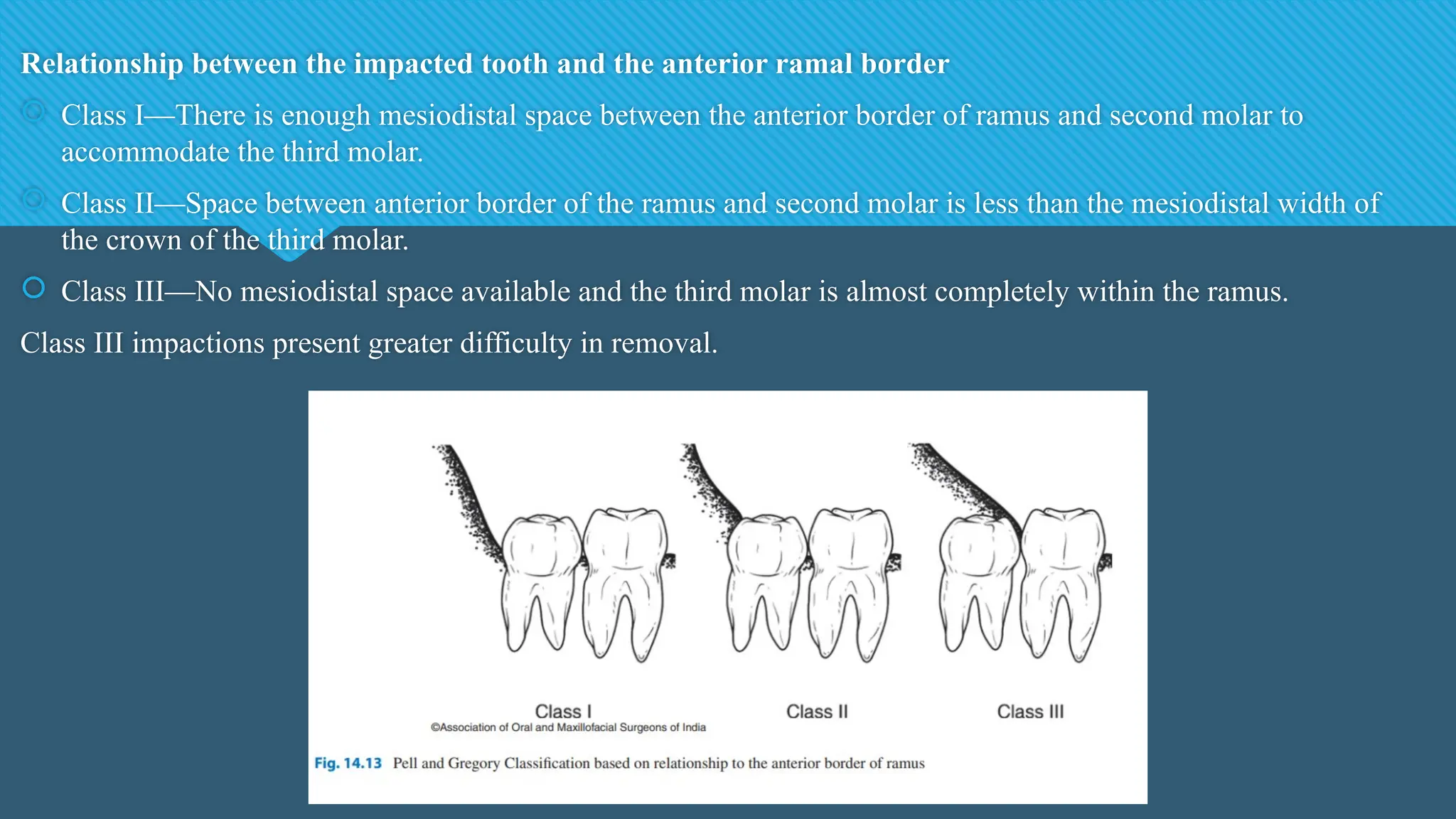

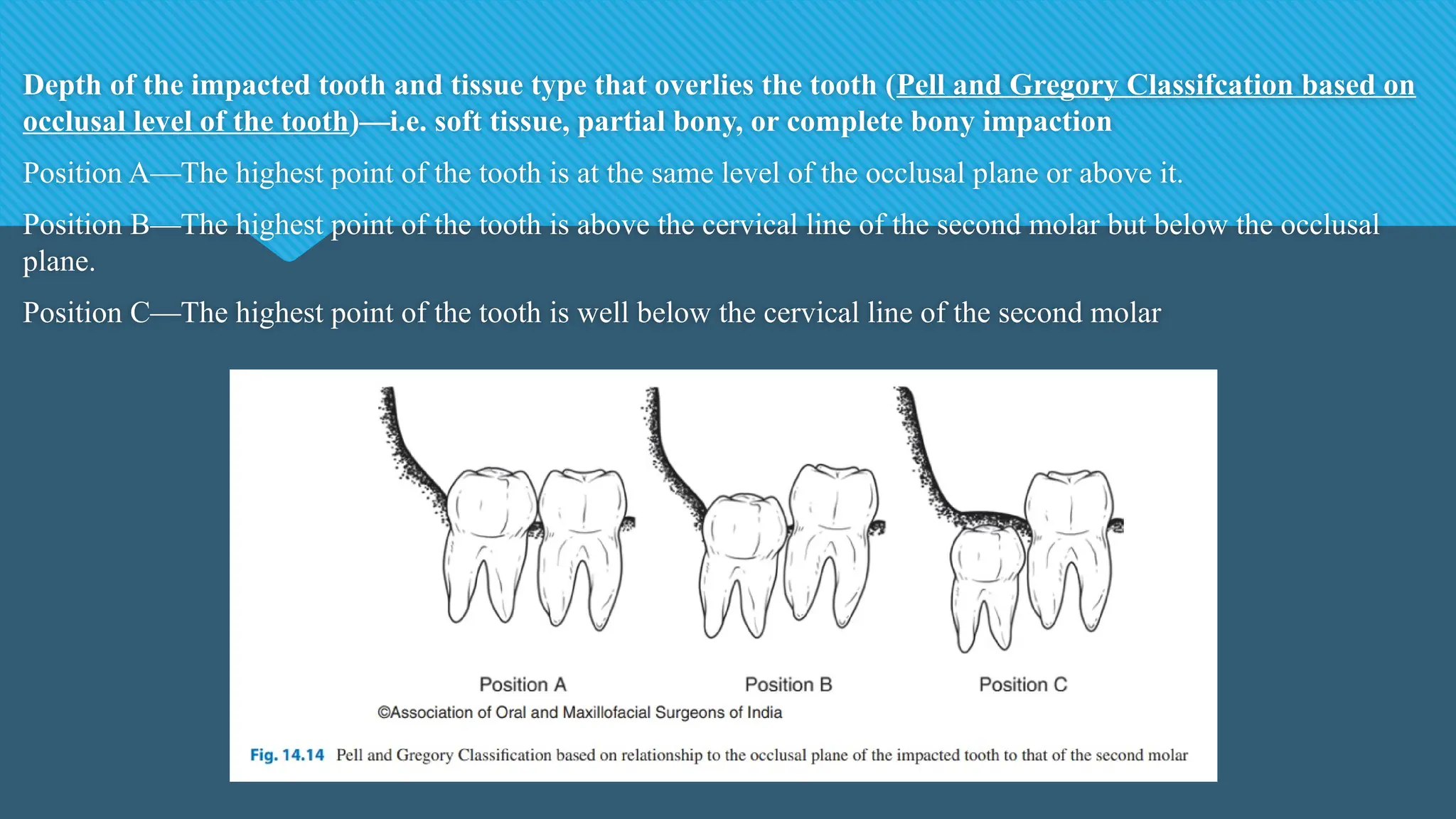

The document discusses third molar impactions, highlighting that surgical removal is the most common oral procedure conducted due to their prevalence in the population, with a significant portion being impacted. It details the underlying causes, classifications, and indications for removal, along with related controversies and anatomical considerations relevant to extraction. The document serves as an overview of the complexities and considerations involved in the management of impacted third molars in dentistry.

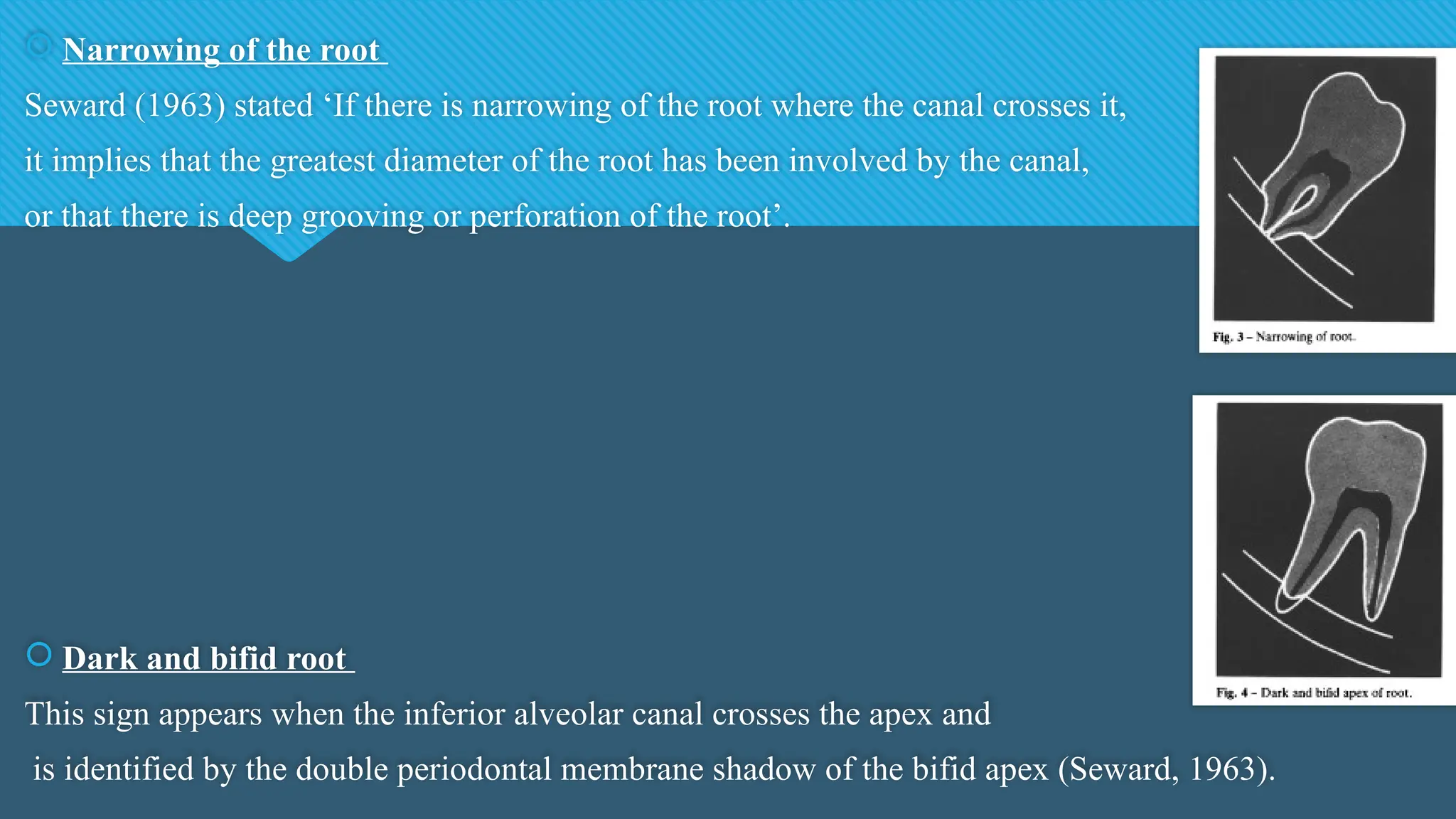

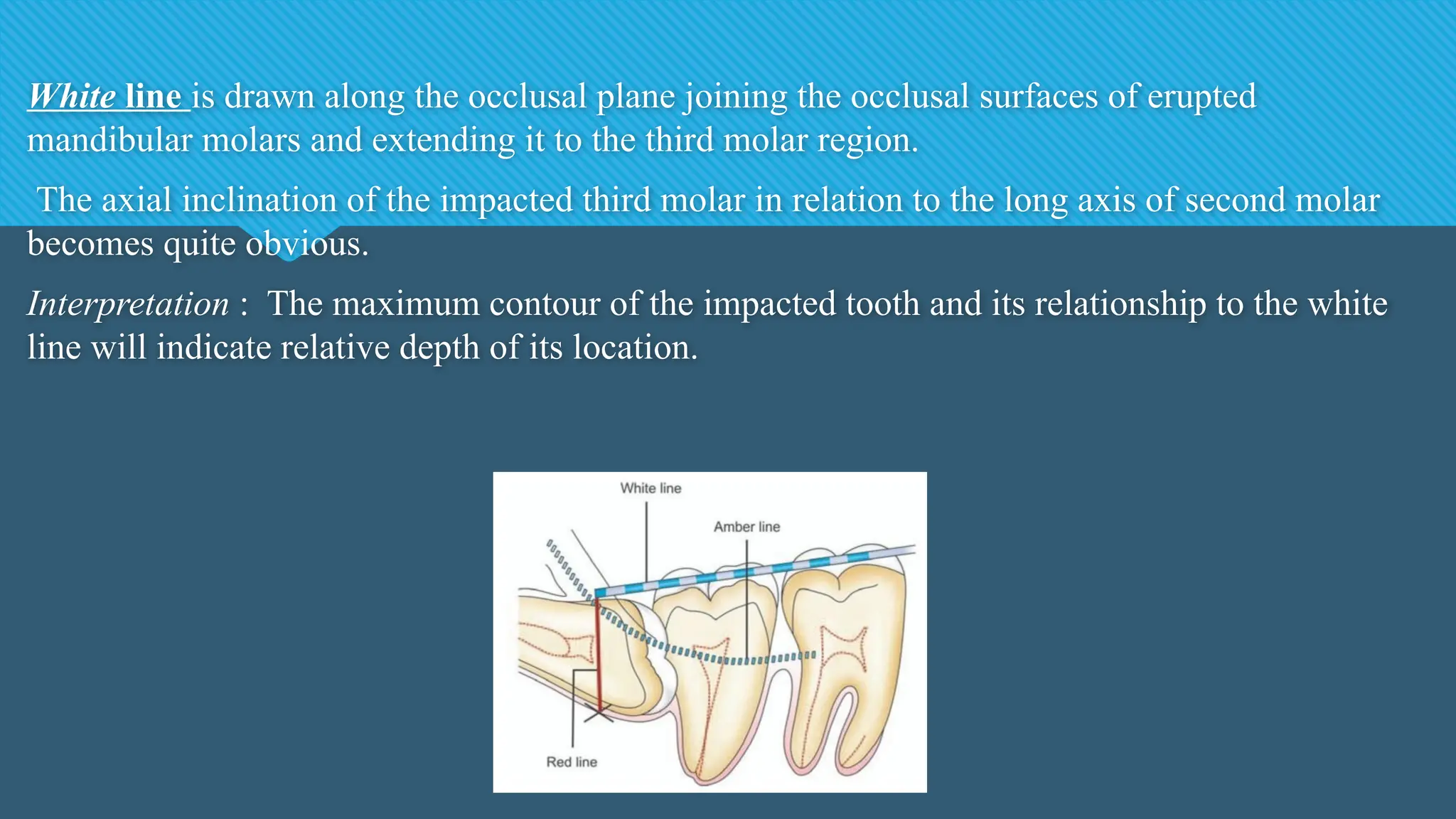

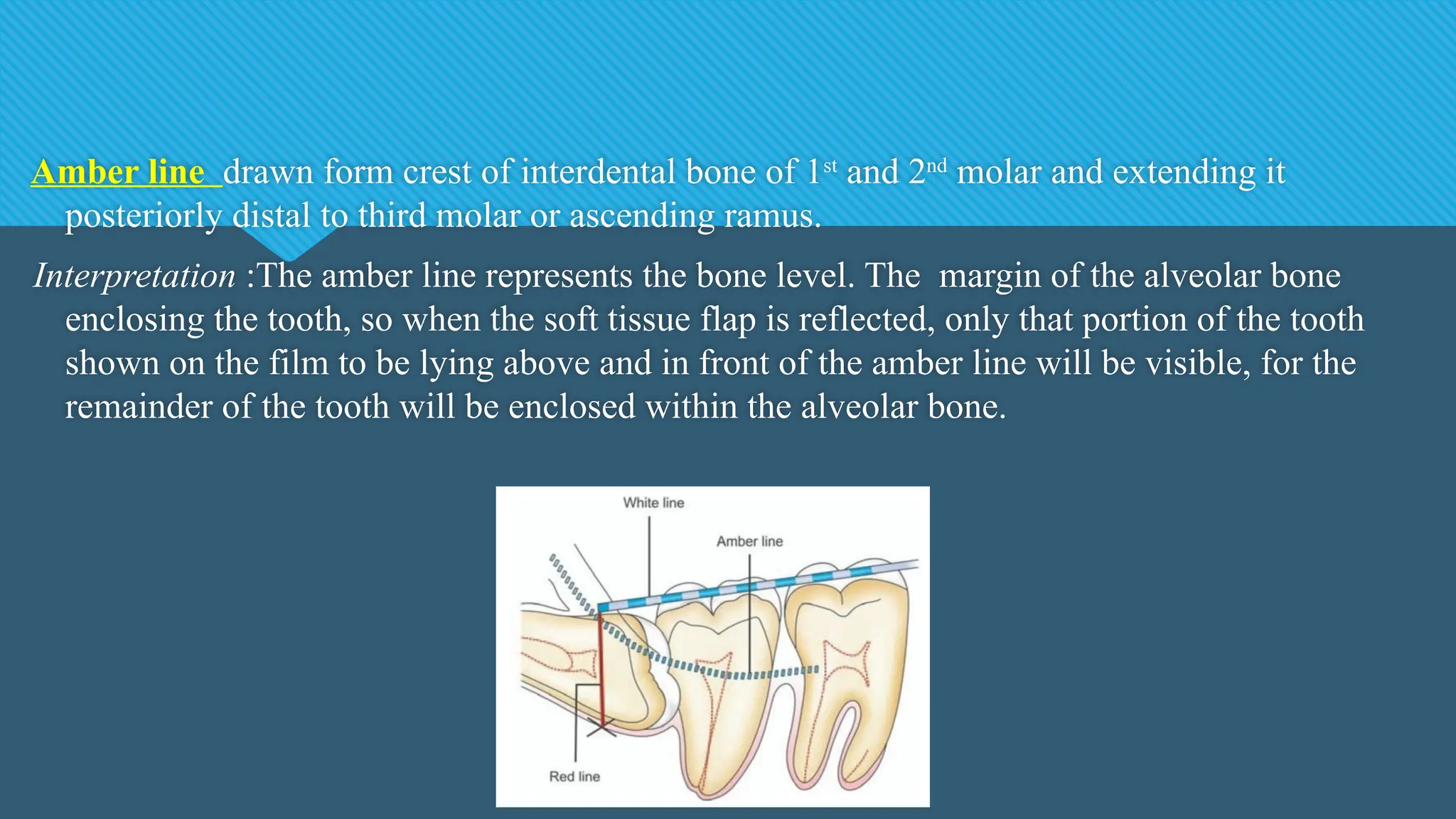

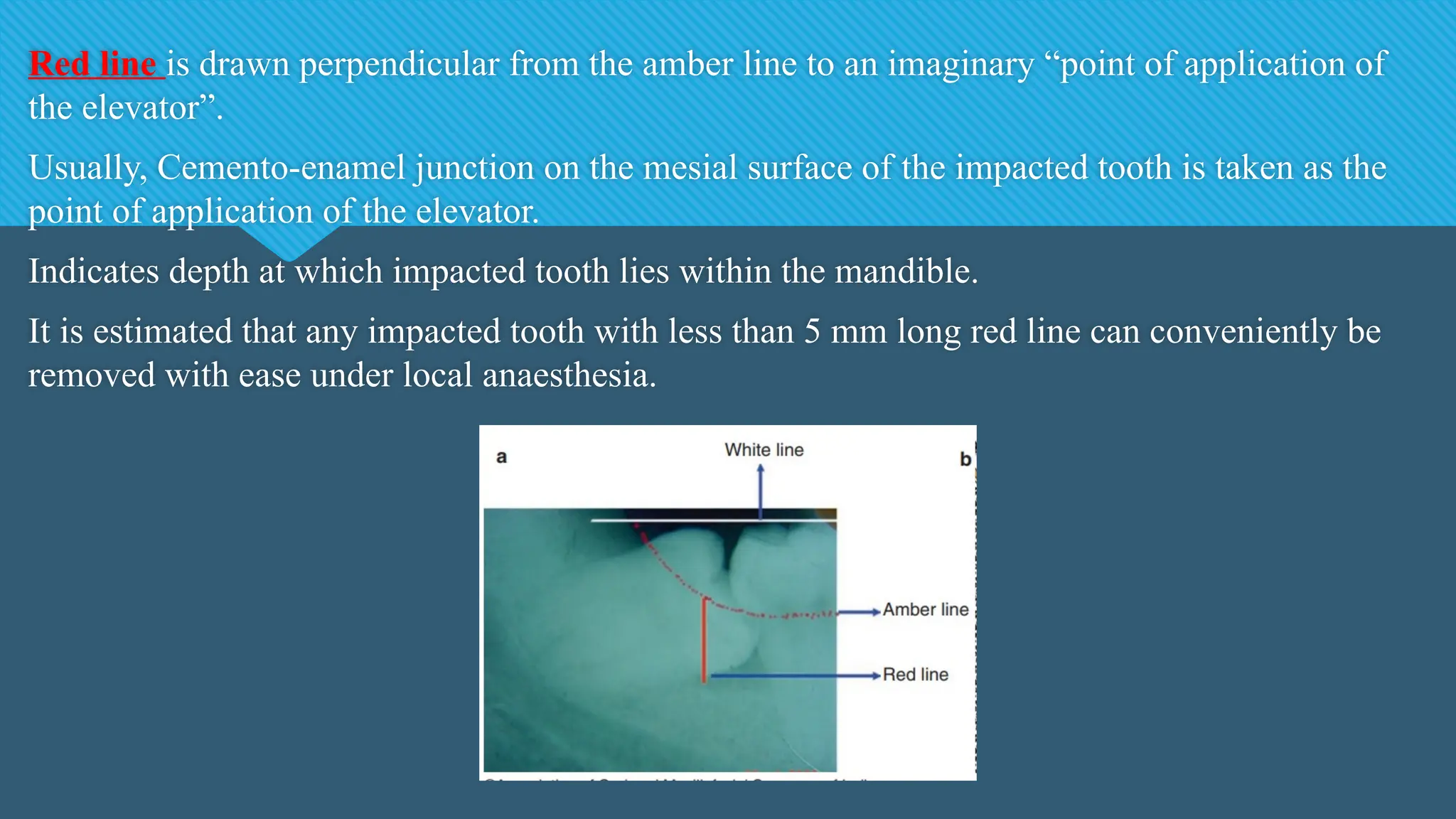

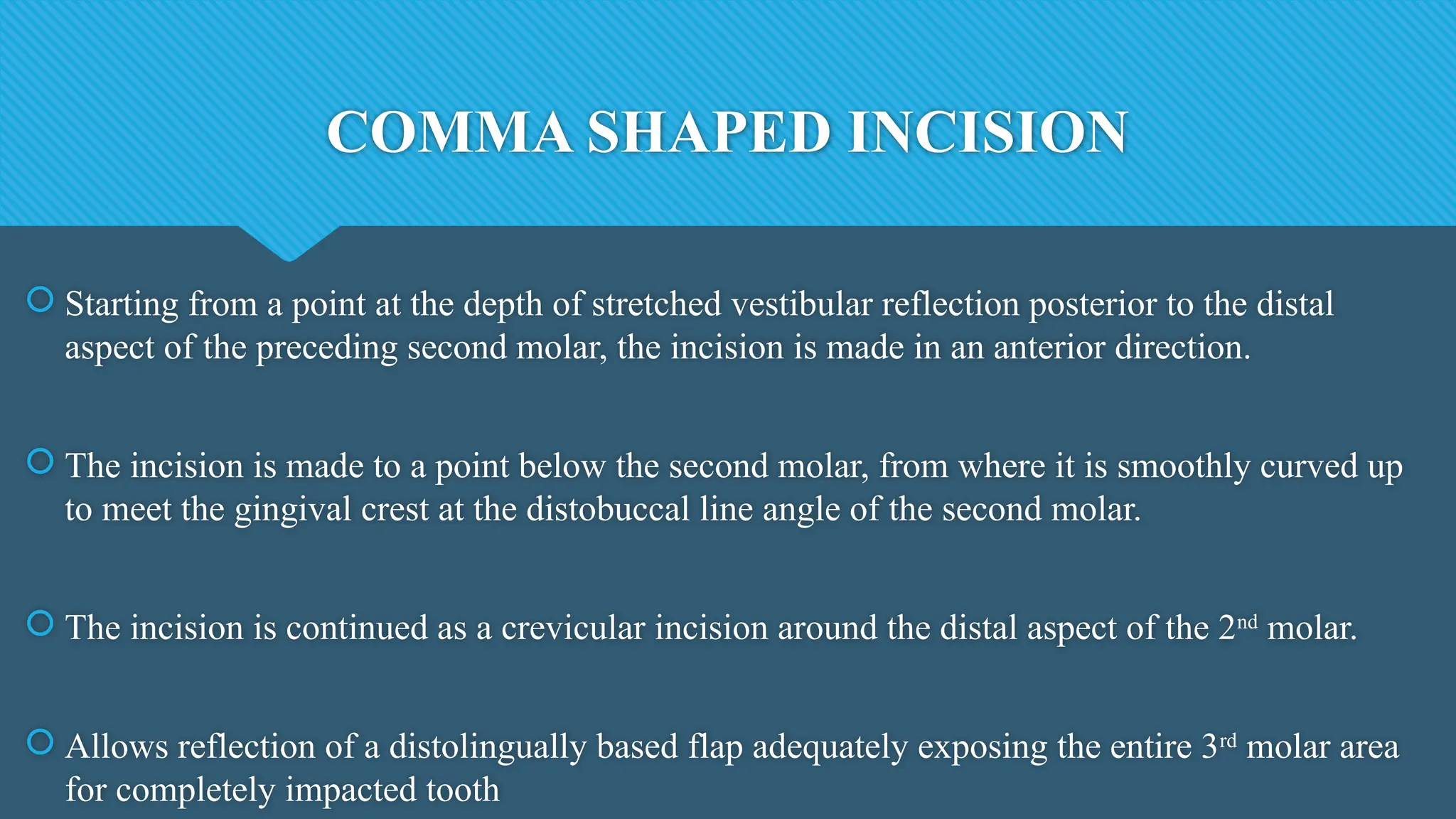

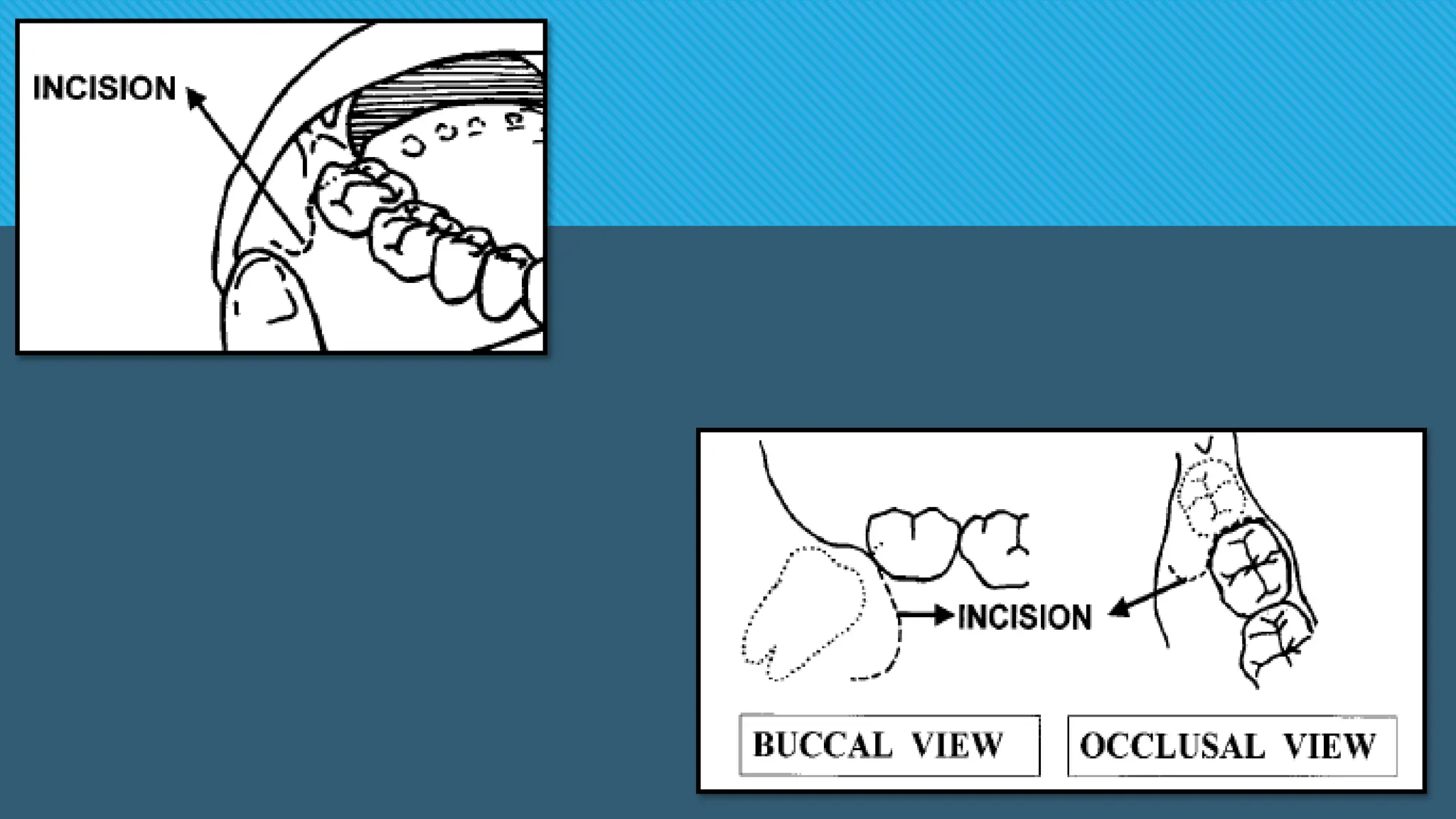

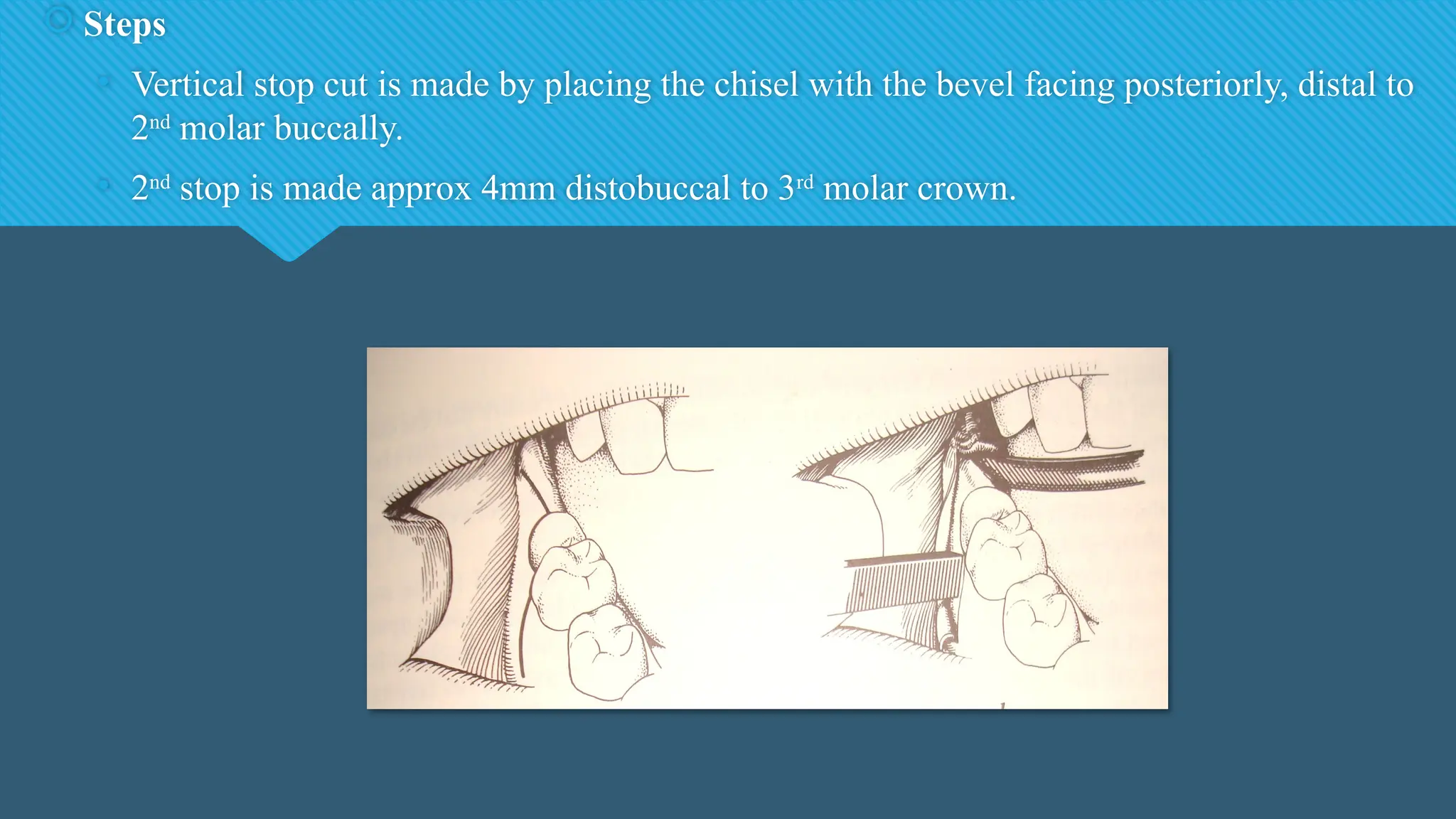

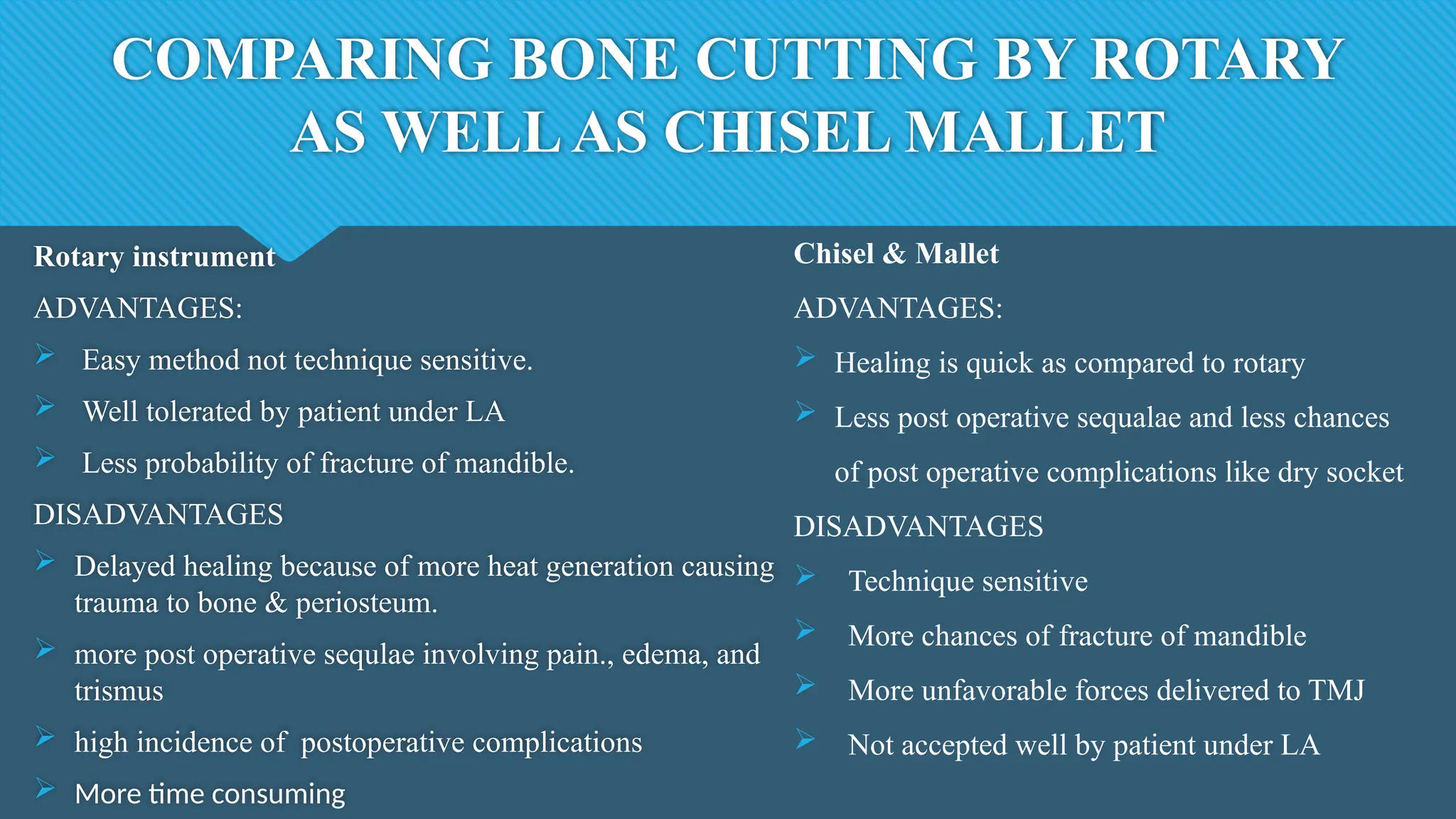

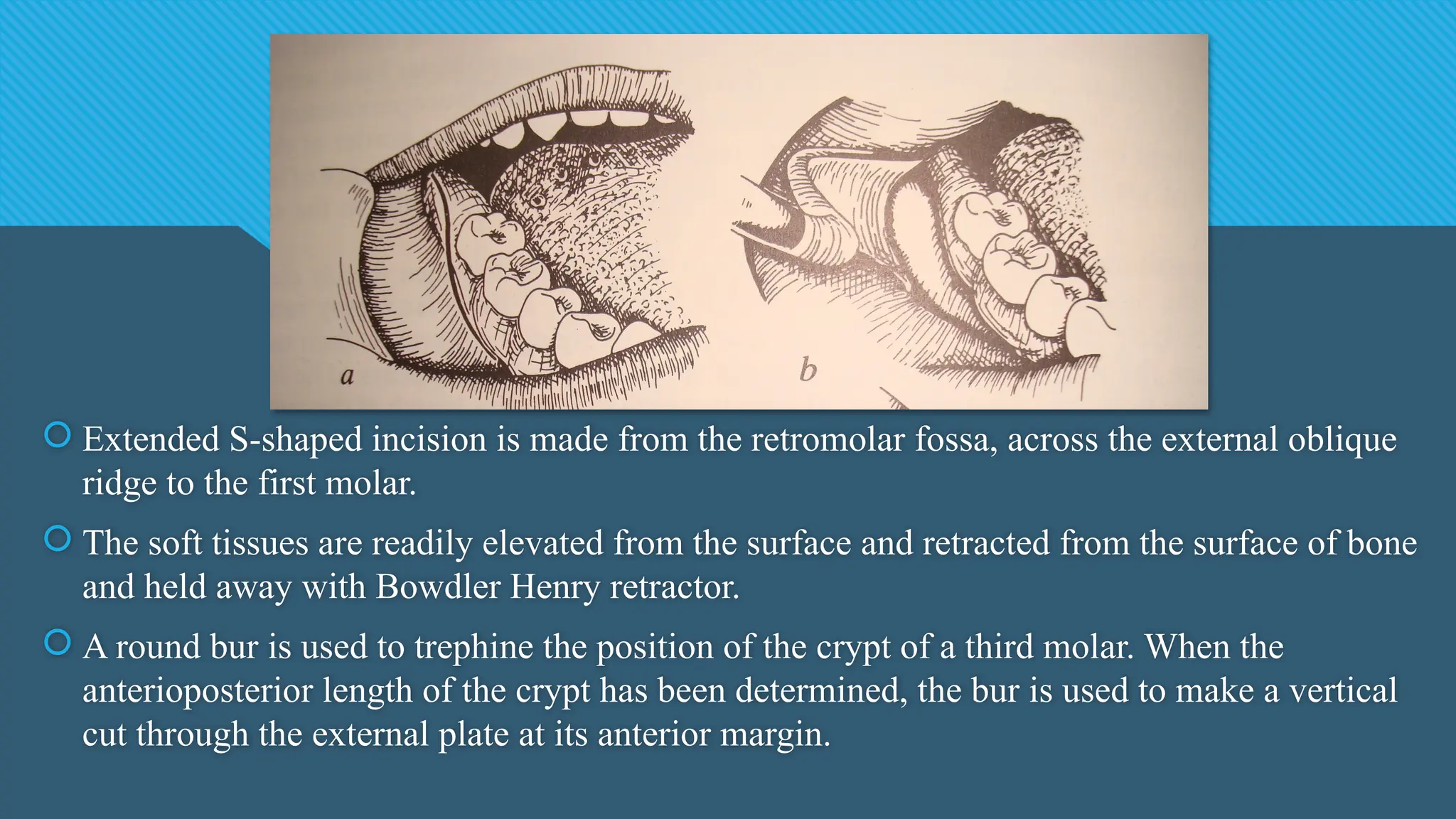

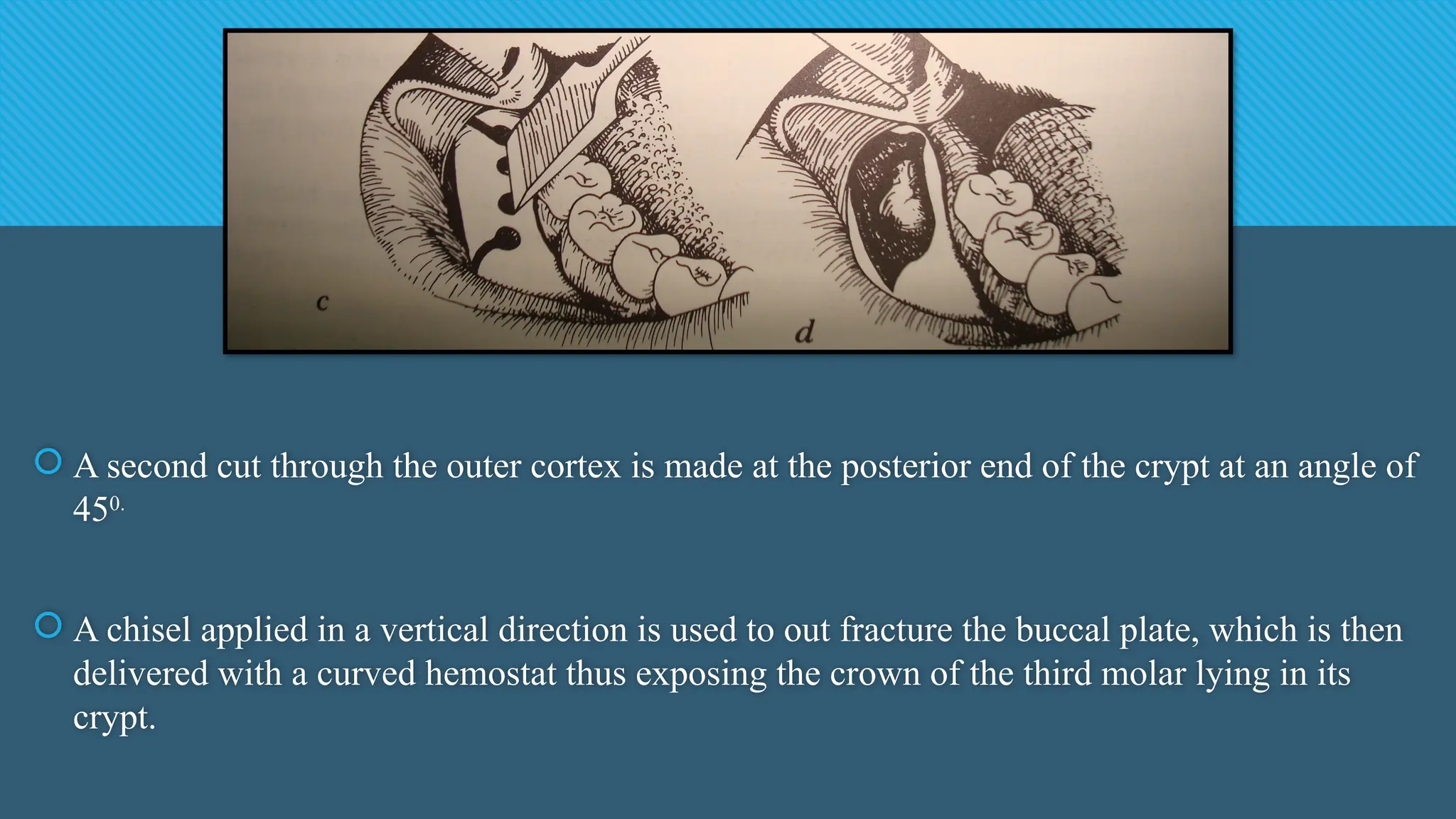

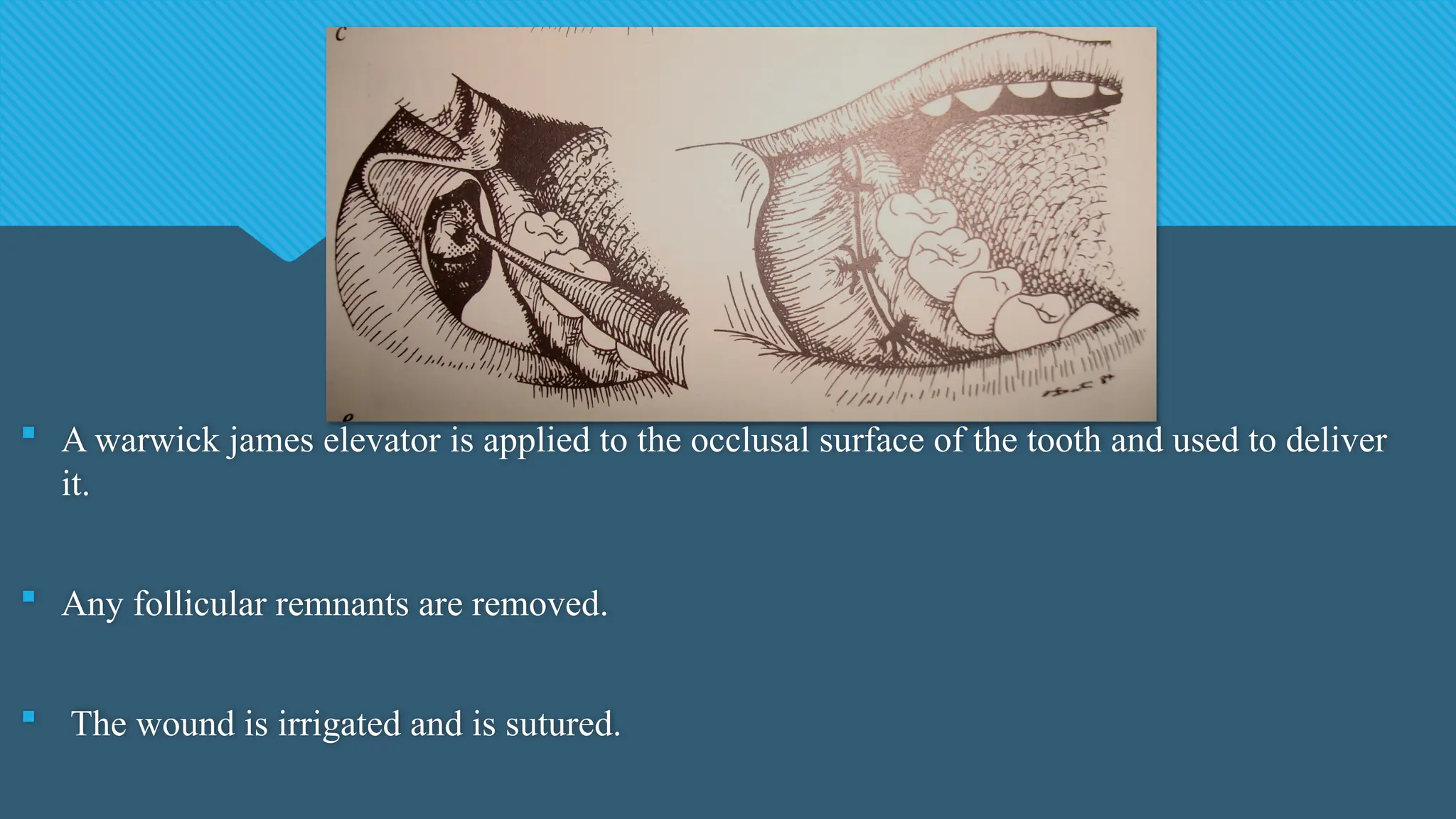

![2. Phylogenic theory: Nature tries to eliminate the disused organs i.e., use makes the organ

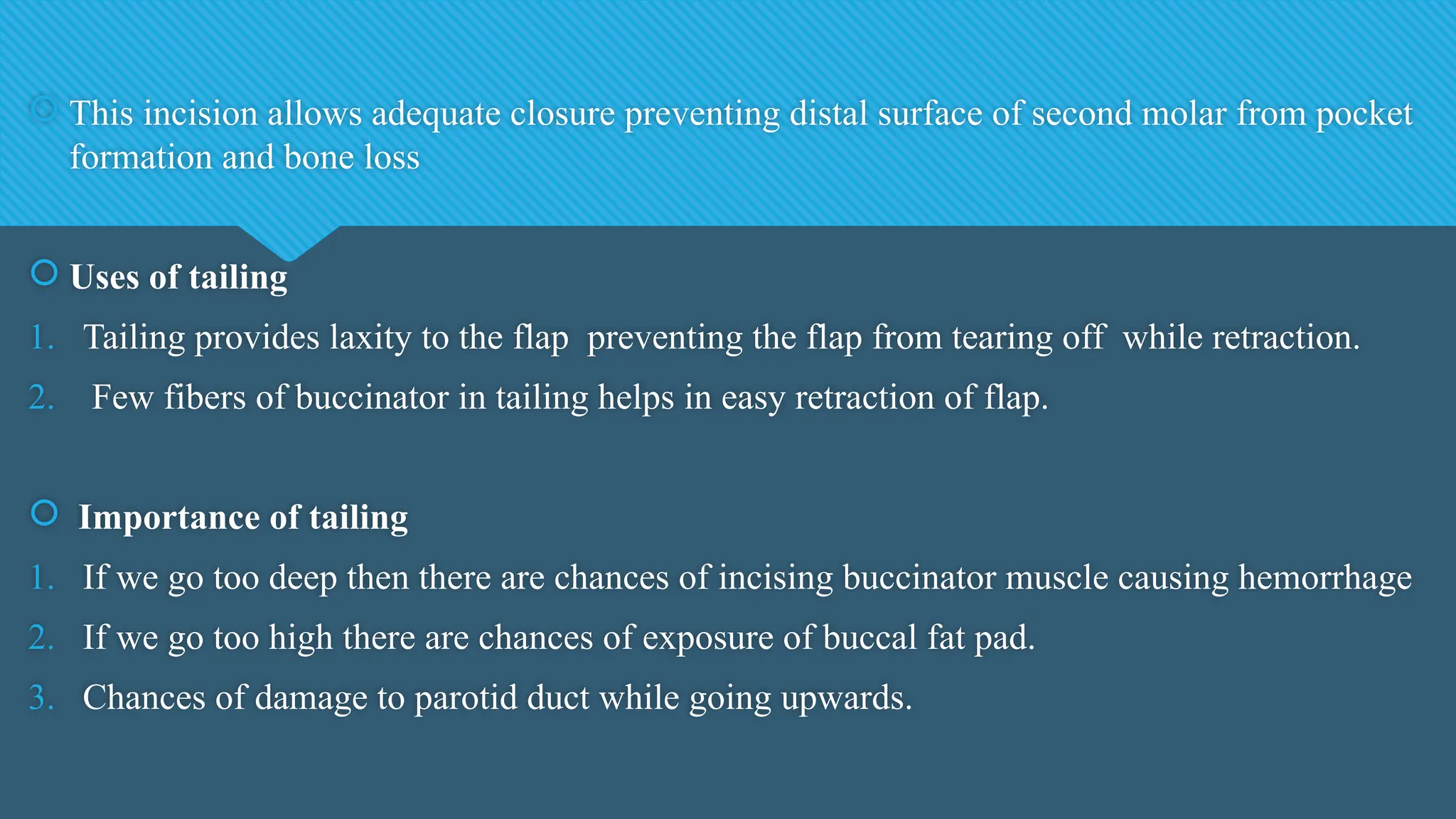

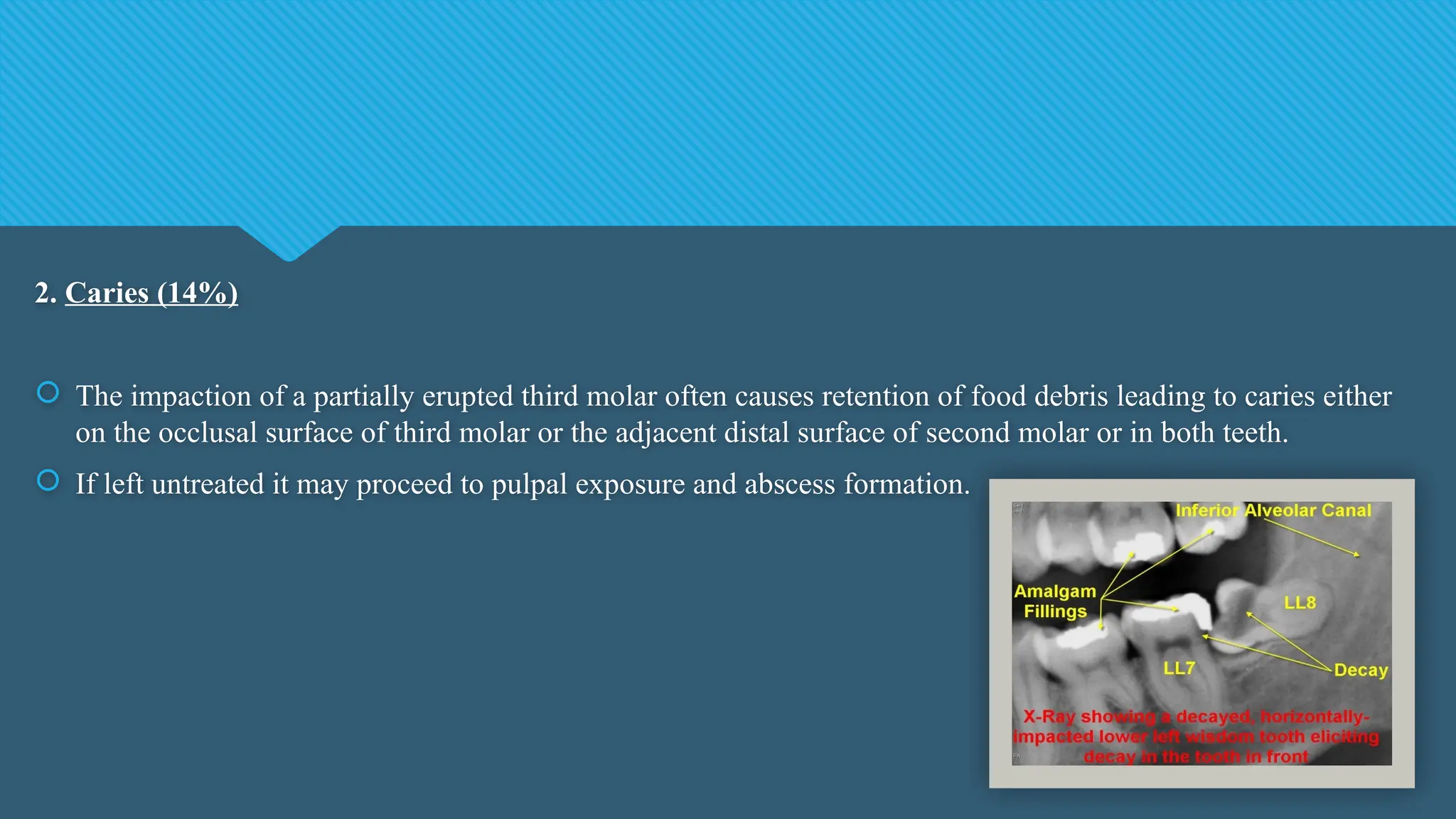

develop better, disuse causes slow regression of organ. [More-functional masticatory force

– better the development of the jaw] Due to changing nutritional habits of our civilization,

use of large powerful jaws have been practically eliminated . Thus, over centuries the

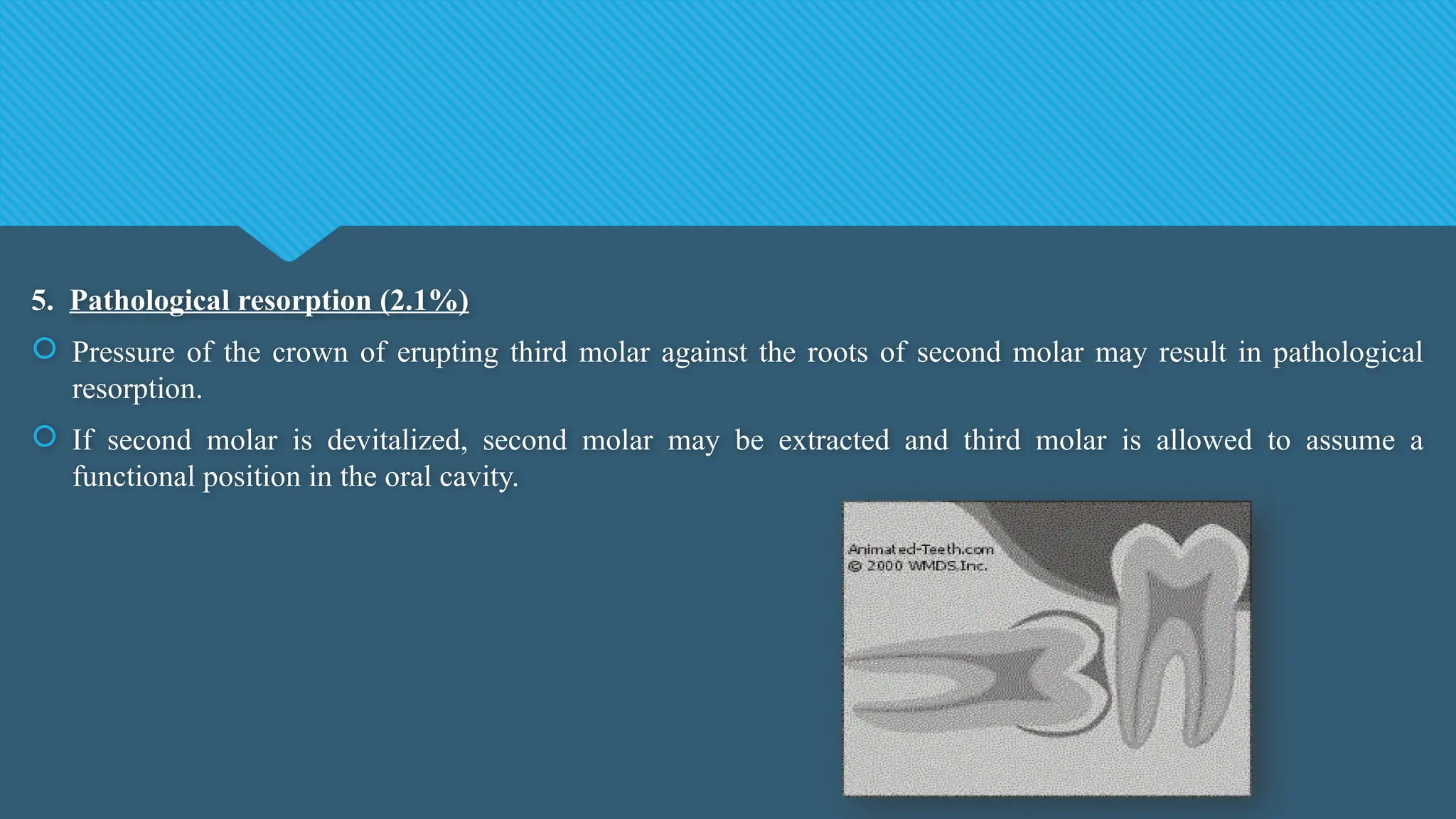

mandible and maxilla decreased in size leaving insufficient room for third molars.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thirdmolarimpactions-241125132125-f4e1851f/75/THIRD-MOLAR-IMPACTIONS-and-its-management-13-2048.jpg)

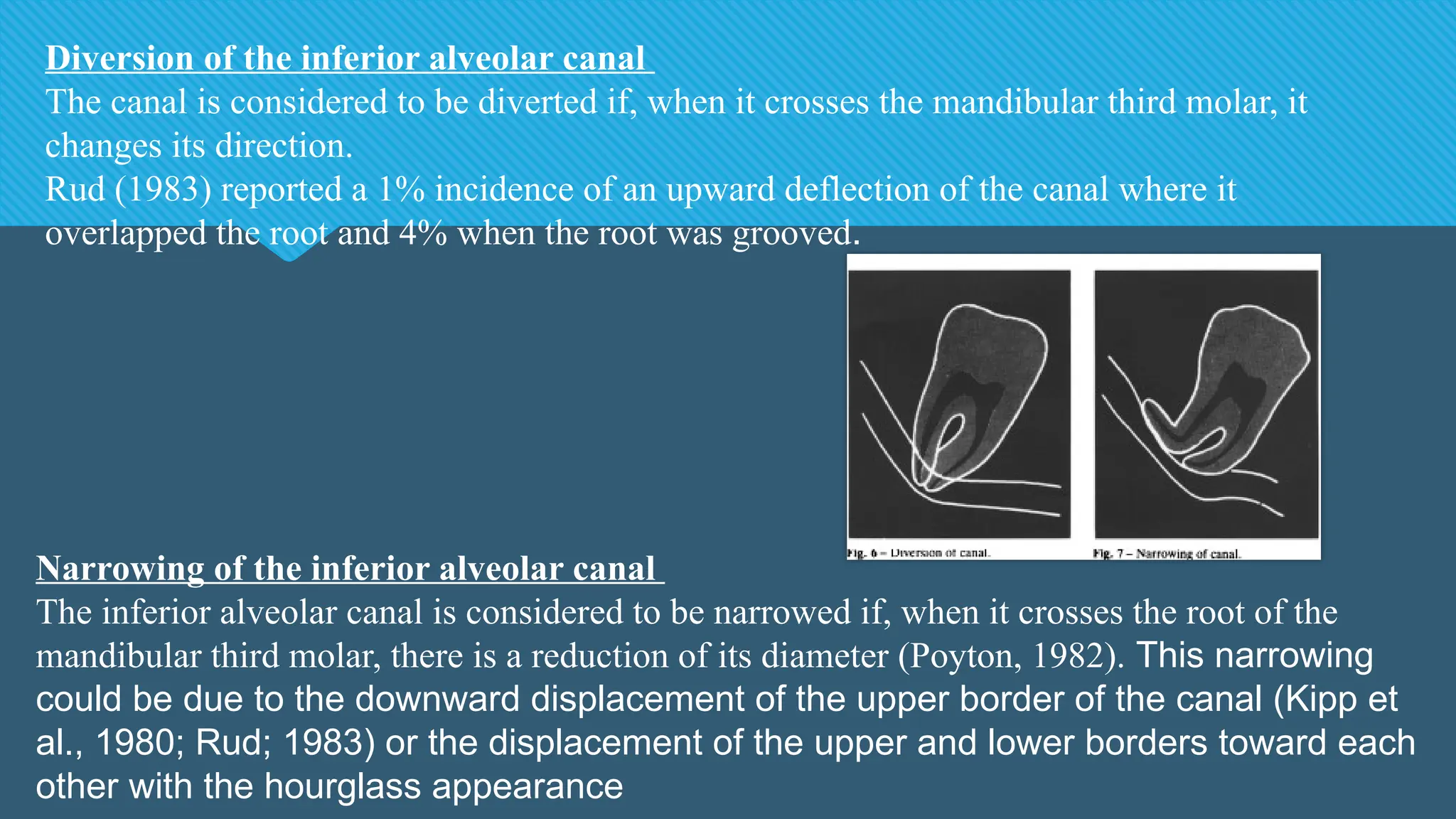

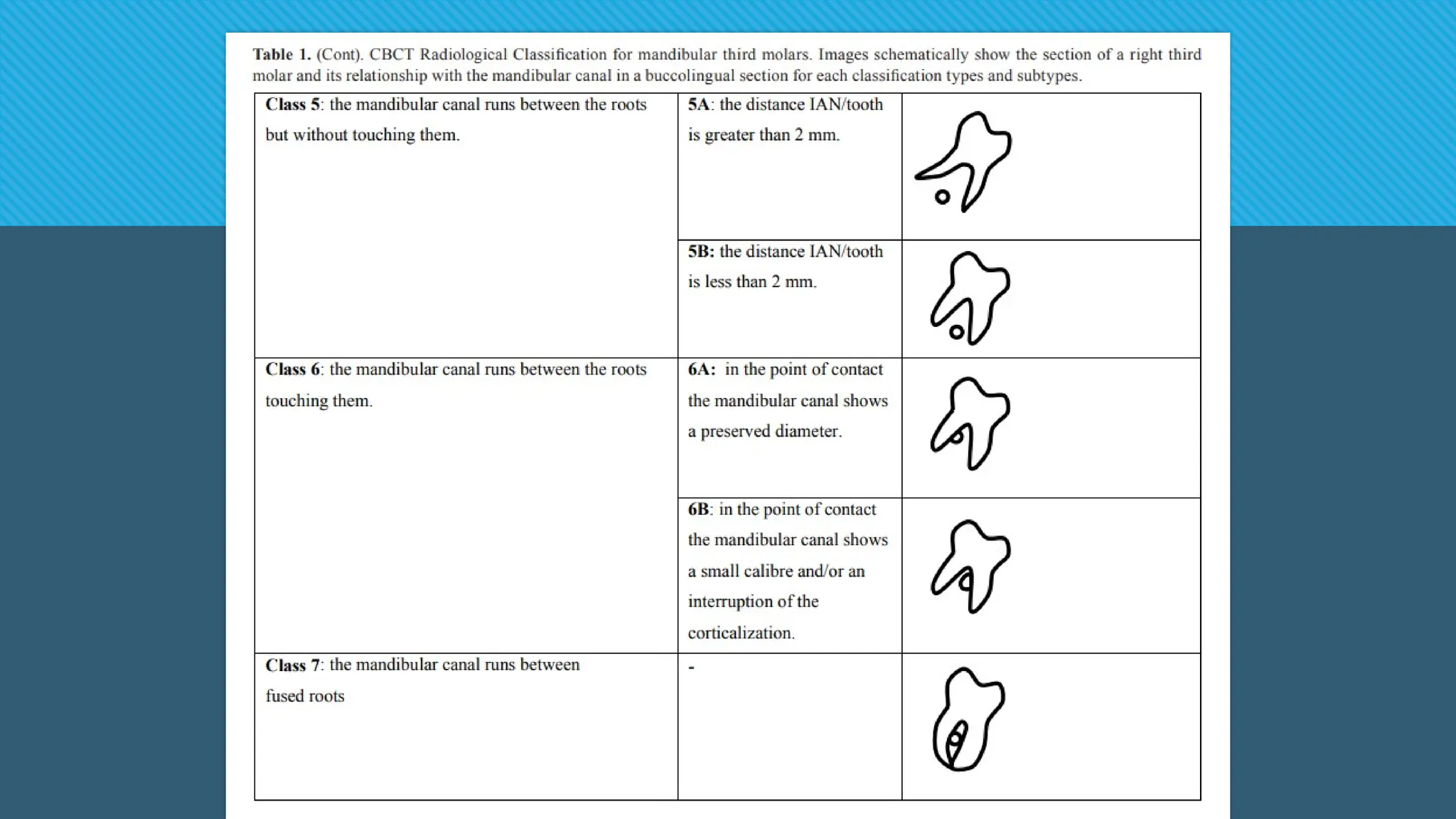

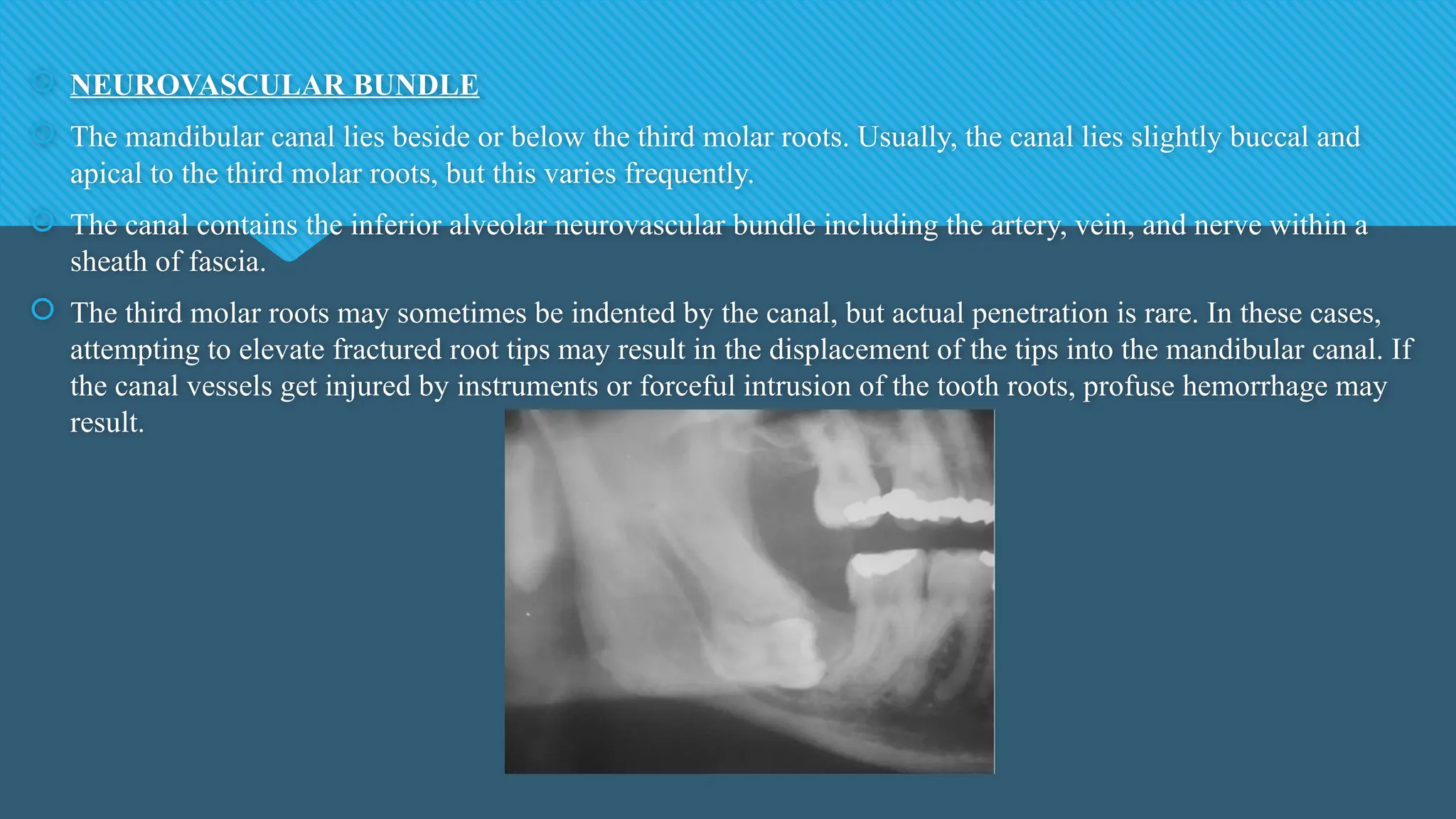

![Angulation of the third molar

According to Chang, the greater the angulation of the third molar, the more difficult it is

to remove and to maintain oral hygiene.

Periodontal pocket

There are occasions when removal of third molars can either create or exacerbate

periodontal problems on the distal aspect of the lower second molar.[9] The most

important predictor of the final bone level behind the second molar was the bone level on

the distal aspect of the second molar on completion of removal of the third molar](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thirdmolarimpactions-241125132125-f4e1851f/75/THIRD-MOLAR-IMPACTIONS-and-its-management-51-2048.jpg)