This document is a master's thesis project that examines the representation of herders in Mongolia's democracy and their level of civic participation. It analyzes the structure of Mongolia's government, measurements of its level of democracy, political parties and ideologies, voter turnout rates, indicators of civil society engagement among herders, and forms of herder activism. The author concludes that while Mongolia has been largely successful as a democracy, herders are less represented in civil society networks and online, though some politicians advocate on their behalf. The future of herding is uncertain as environmental and economic changes threaten that livelihood.

![28

violence. The difference: English people have in modern times been mostly farmers and urban-

dwellers, whereas those from more remote parts of the British Isles have been herders with no

defined territory, so they have been vulnerable to theft by other herders and needed to vigilantly

guard their flock. If this is the case among the Mongolian herders, then it is certainly an obstacle

to political engagement, since grassroots political activity can hardly occur without cooperation.

Herders do not always isolate themselves from each other. That is, they do not associate

only with members of their household, however big their families are. The level of association

between households differs depending on the location. In the Gobi desert, which is extremely

sparsely-populated, households generally prefer to keep to themselves. According to Endicott:

Most Gobi families nomadize alone, not with other herder families. The Gobi

differs from many areas of central-northern Mongolia where campsites are well

populated by several gers [yurts] … only in atypical spots in the Gobi where

water and pasture were more plentiful did he [Simukov, another researcher] find a

larger gathering of gers, but even in these cases, the gers were spread out

individually or in pairs throughout the area.

(p. 28)

I personally observed, while riding on the train from Zamyn-Üüd on the Chinese border to

Ulaanbaatar in the north, that yurts appeared in isolation in the southern part of the country (the

desert), while they were more often clustered together after the train entered the grassland (it

was also very obvious which of these two ecosystems the train was in). In the grassland herders

are far more likely to assemble into ayils, groups of yurts encamping together (ibid).

Explanations for this regional difference are not airtight; for example, Endicott argues

that herders in the grassland need each other’s protection against wolves, which are less of a

problem in the desert (p. 40-4). It would seem, though, that the desert is altogether a more

difficult place to survive, so they would need each other’s help even more. What matters for the

purpose of this paper is that herder households can often be found in communities – albeit often](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cfd6abe3-8b2d-4b74-8a7e-844fba578fb4-160110120227/75/Thesis-deadline-day-33-2048.jpg)

![36

sees democracy as a means of achieving what his religion aims to achieve. He writes poetry as

part of his job as an activist. However, like Elbegdorj, he is also highly pragmatic. He makes

great efforts to optimize the representation of herder and their proxies in the Khural and cabinet.

He has helped to organize demonstrations, bring herders together to form local organizations,

and encouraging them to utilize the most rudimentary form of participation in the political

process: voting. Whereas Elbegdforj entered the scene later, Battulga was among the “Original

Thirteen” politicians, including Baabar, and ministers who have are renowned among their

people for engaging people in the political process whose voice otherwise might not be heard.

To what extant are herders involved in policy-making? To do so, they do not always need

to be involved in the national government. Governments exist at the level of the province, the

sum, and in some cases the bagh. These sub-national governmental bodies have no power to

make their own laws, however the way in which they influence laws is shaped by who is

influencing the policy-making process, or who is carrying it out. In regions of the country where

the overwhelming majority are herders, naturally they will dominate in government, especially if

they are elected by locals (although herders need to compete with lobbyists). Endicott writes of a

local policy community that exists between sum- and bagh-level governments and “‘experienced

elders’ who are themselves the leaders of khot ails [camps of herders]” (p. 110). These local

governments have a variety of functions such as resolving land disputes and other issues in

which there is no need to get the national government involved.

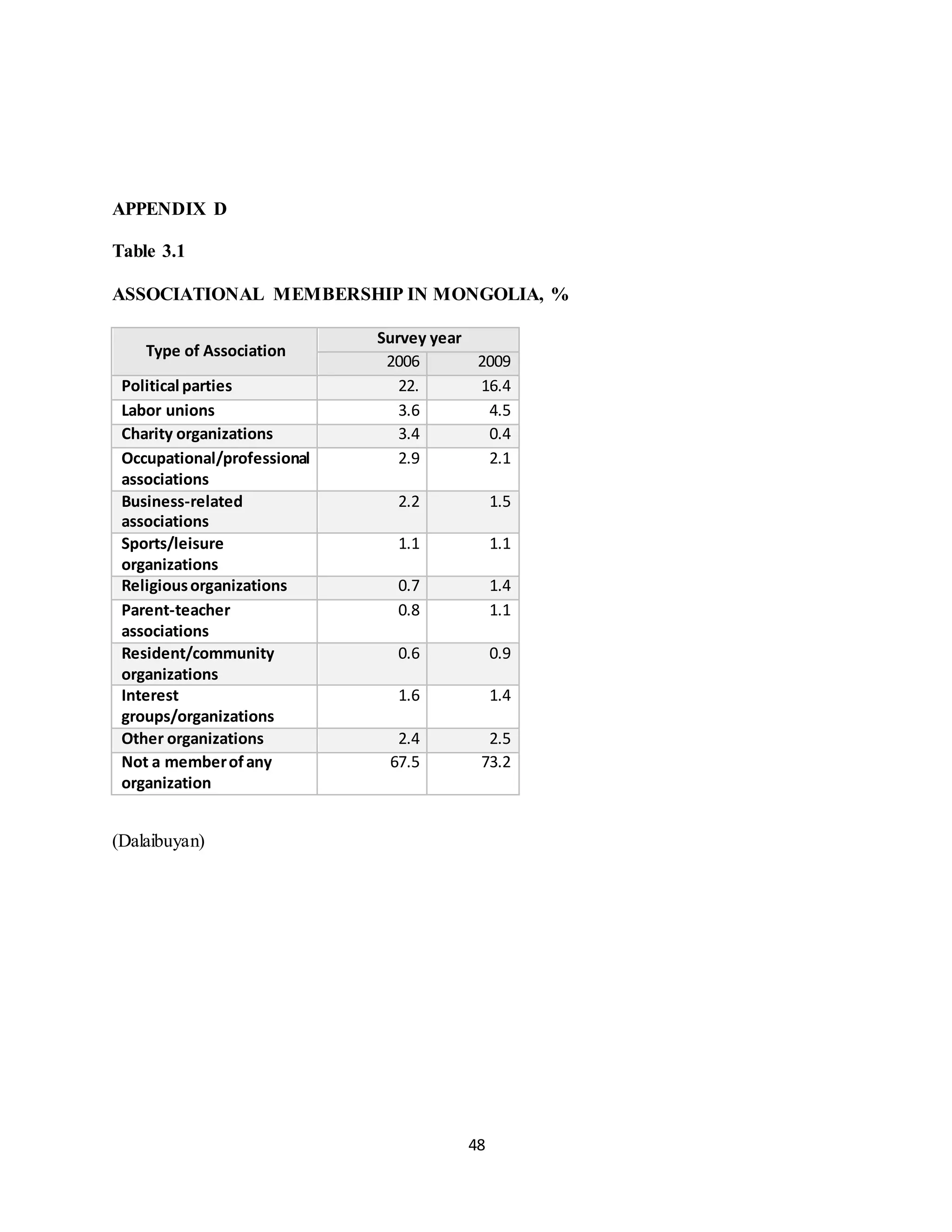

Civil Society

Mongolia’s current Constitution affords its people all the civil liberties of a first-world

democracy. Dalaibuyan writes about the cultural framework for civil society in post-communist](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cfd6abe3-8b2d-4b74-8a7e-844fba578fb4-160110120227/75/Thesis-deadline-day-41-2048.jpg)