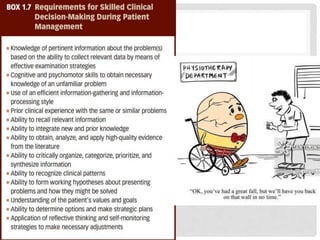

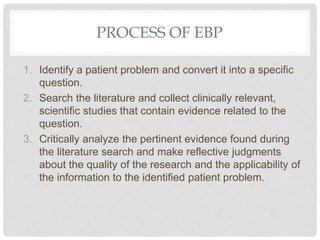

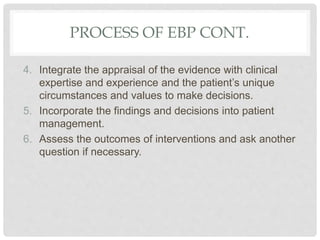

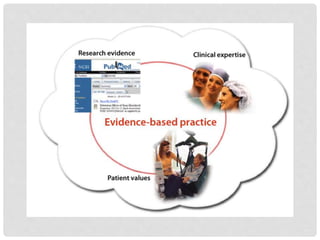

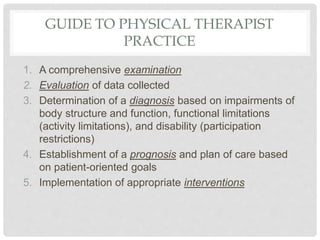

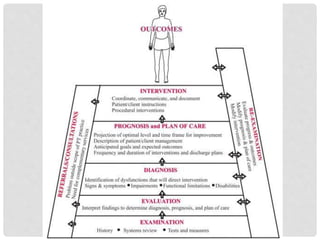

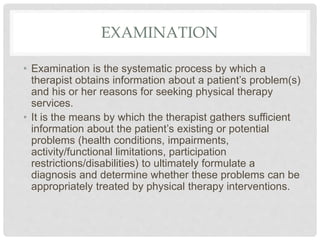

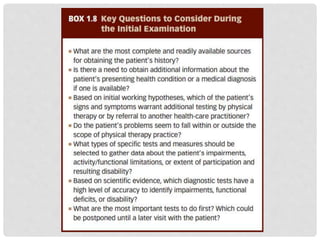

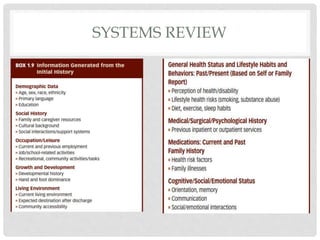

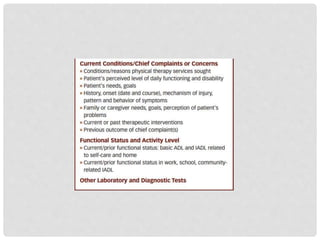

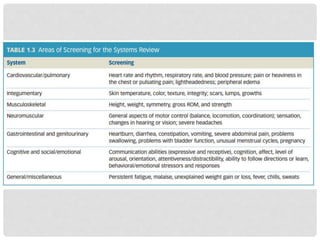

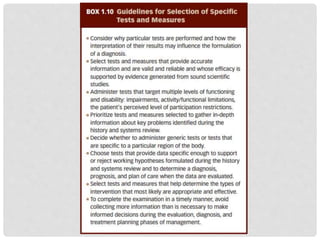

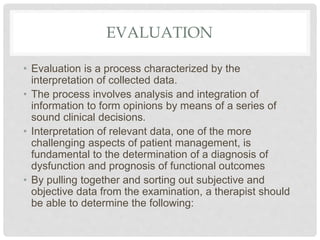

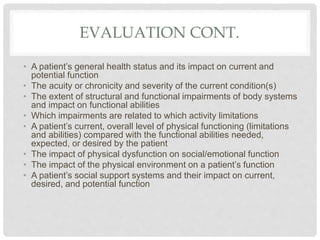

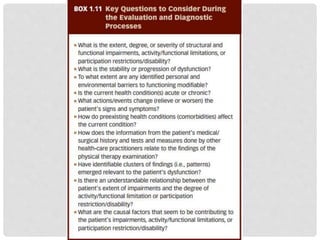

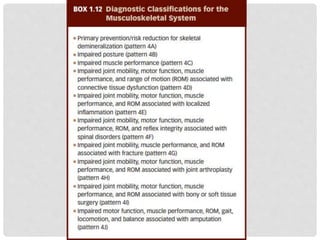

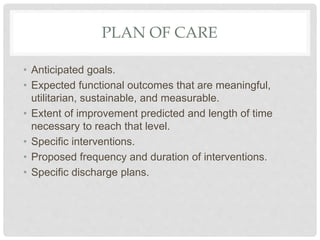

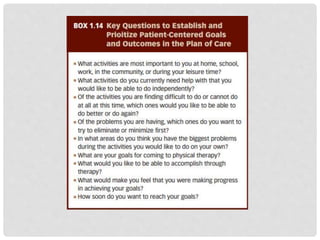

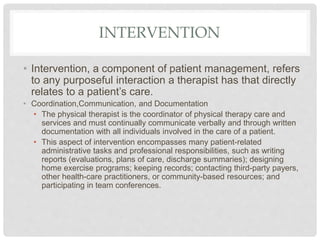

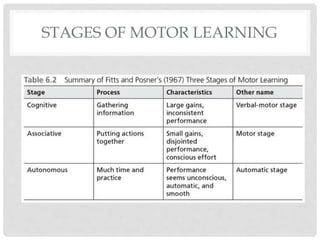

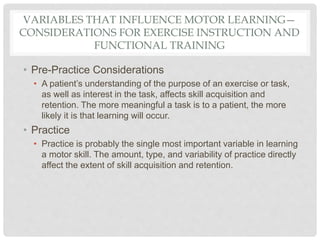

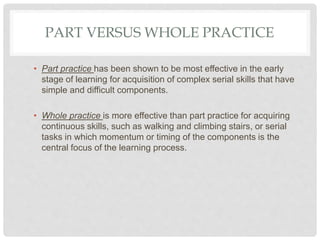

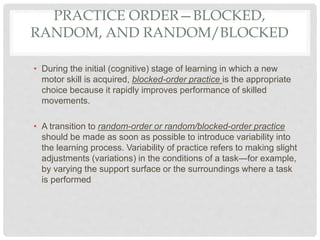

This document discusses clinical decision making in physical therapy. It covers evaluating a patient through examination, determining a diagnosis, establishing a prognosis and plan of care, implementing interventions, and assessing outcomes. Key parts of the examination process are gathering a health history, performing systems reviews, and using specific tests and measures. The evaluation involves analyzing collected data to interpret a patient's condition. Evidence-based practice and a patient management model guide clinical decisions. Motor learning principles also inform effective exercise instruction and functional training.