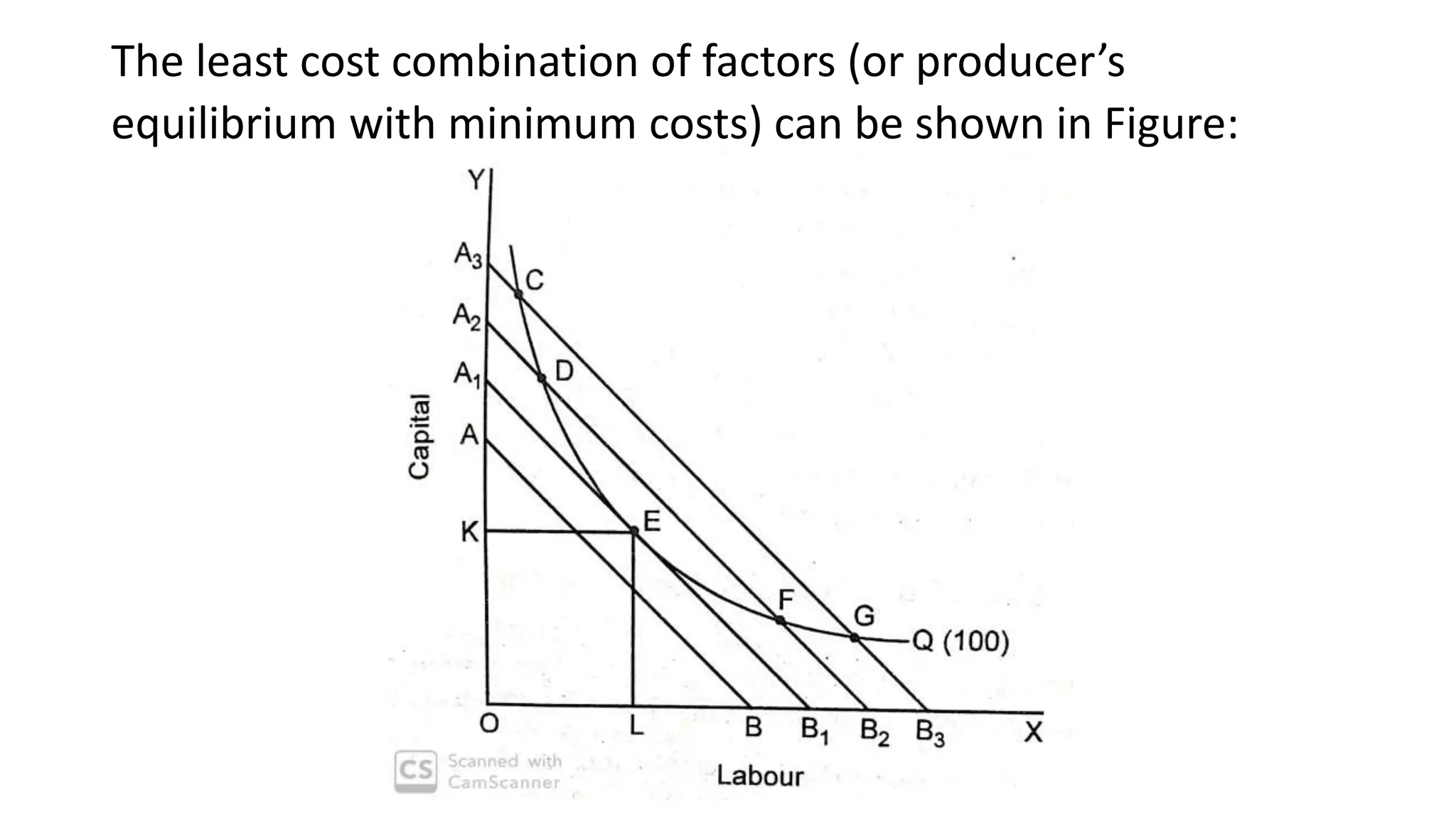

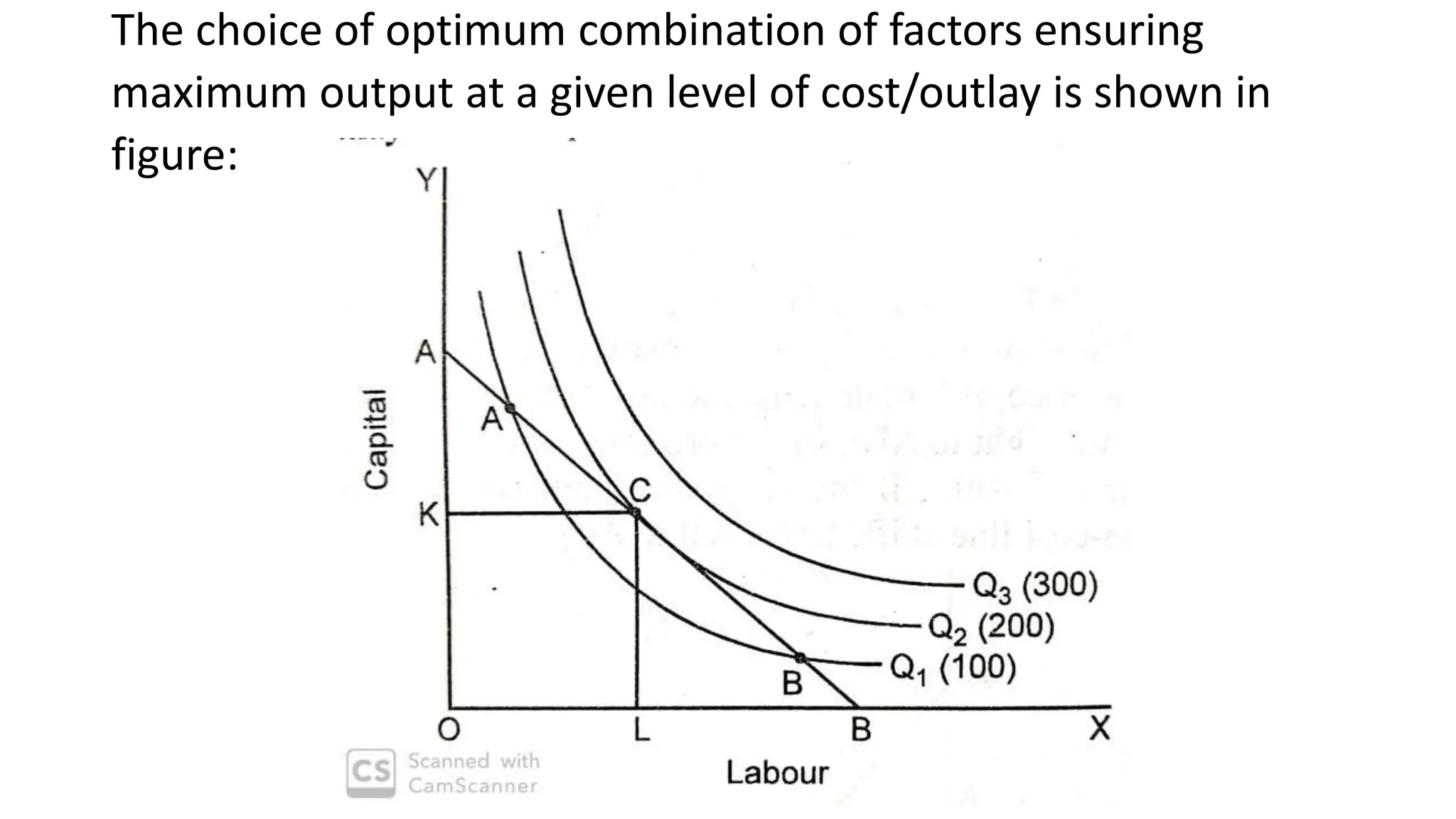

The document discusses the theory of production, defining production as the process of combining inputs to create output for consumption. It explains the production function, elaborates on short-run and long-run production functions, and describes concepts such as returns to a factor, returns to scale, and the law of variable proportions. Additionally, it introduces isoquants and producer equilibrium, highlighting how optimal factor combinations can be achieved for maximum output and minimum cost.

![• The mathematical form of the CES production function may be given as:

𝑄 = 𝛾[𝛿𝐾−𝜌 + 1 − 𝛿 𝐿−𝜌]−1/𝜌

• Where,

• 𝛾 = efficiency parameter (change in efficiency parameter causes a shift in the

production function that can occur as a result of technological or organisational

changes.

• δ = distribution parameter (indicates the relative importance of capital (K) and

labour (L) in various production processes.

• ρ = substitution parameter (indicates the substitution possibilities in the

production process). The elasticity of substitution between factors (σ) for this

production function depends upon this parameter.

• i.e. 𝜎 =

1

1+𝜌

• and where,

• 𝛾 > 0

• 0 ≤ δ ≤ 1

• Ρ ≥ 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/theoriesofproduction1-231229165542-fa6c9610/75/Theories-of-production-Economics-pptx-68-2048.jpg)