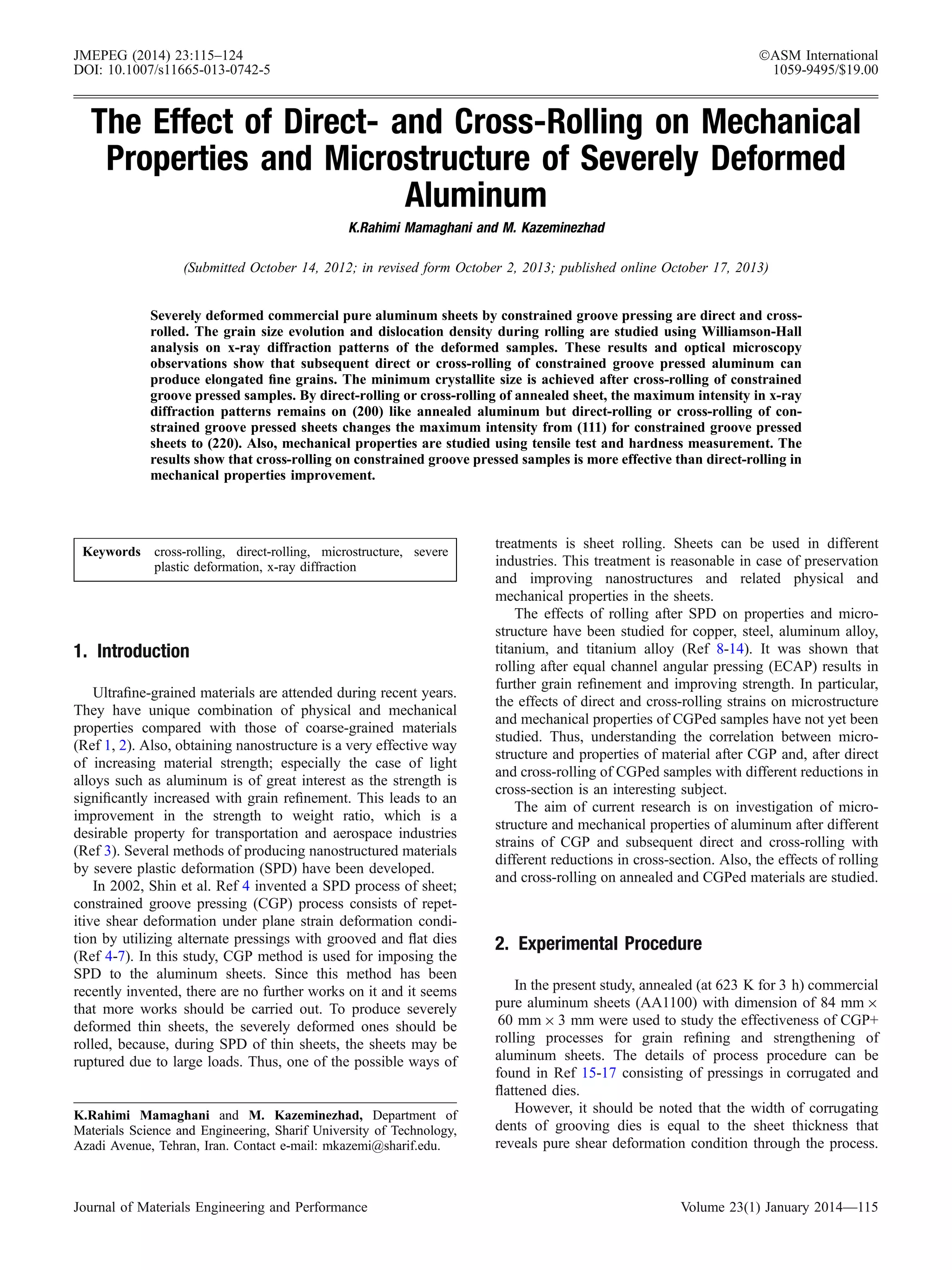

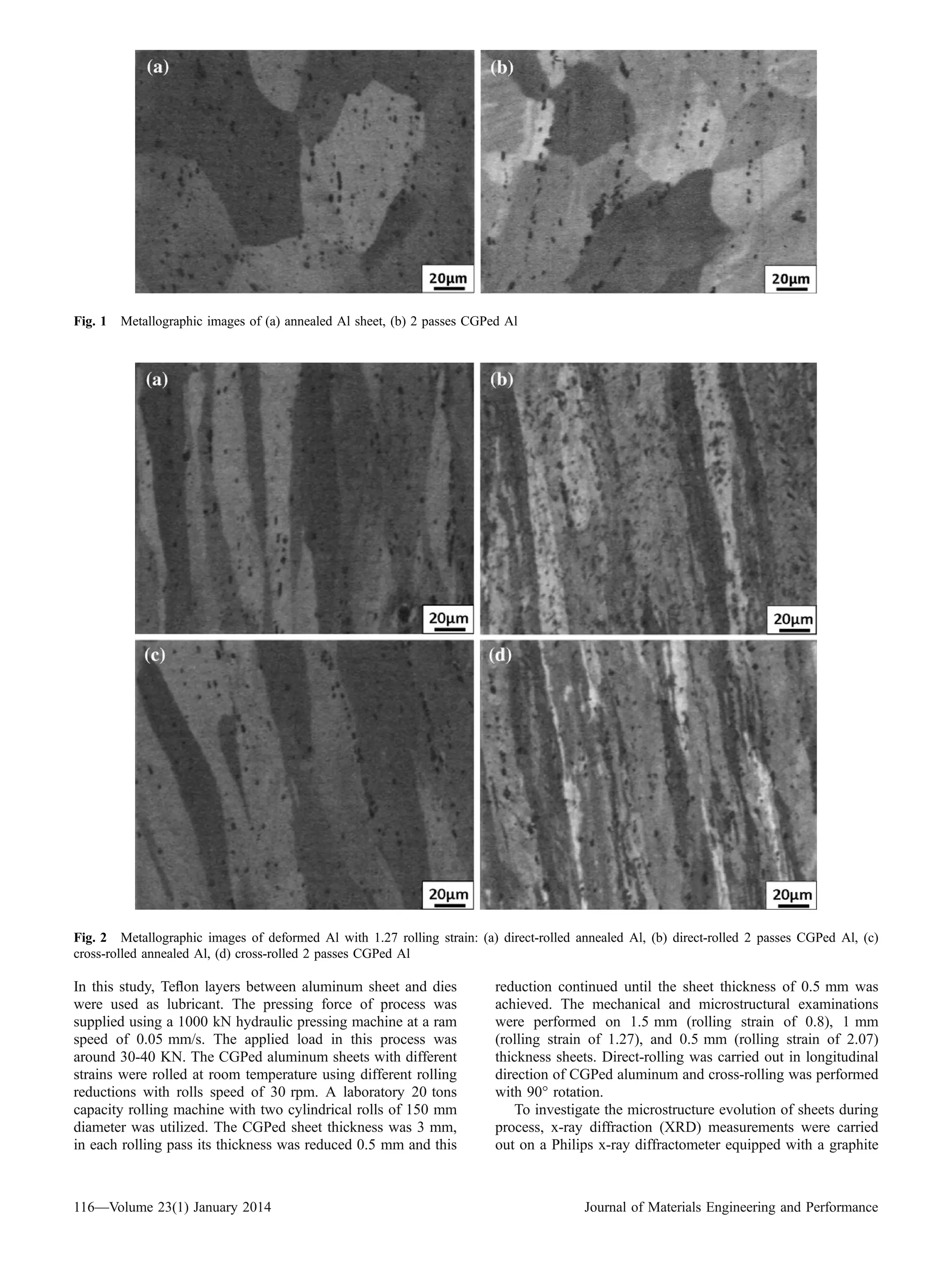

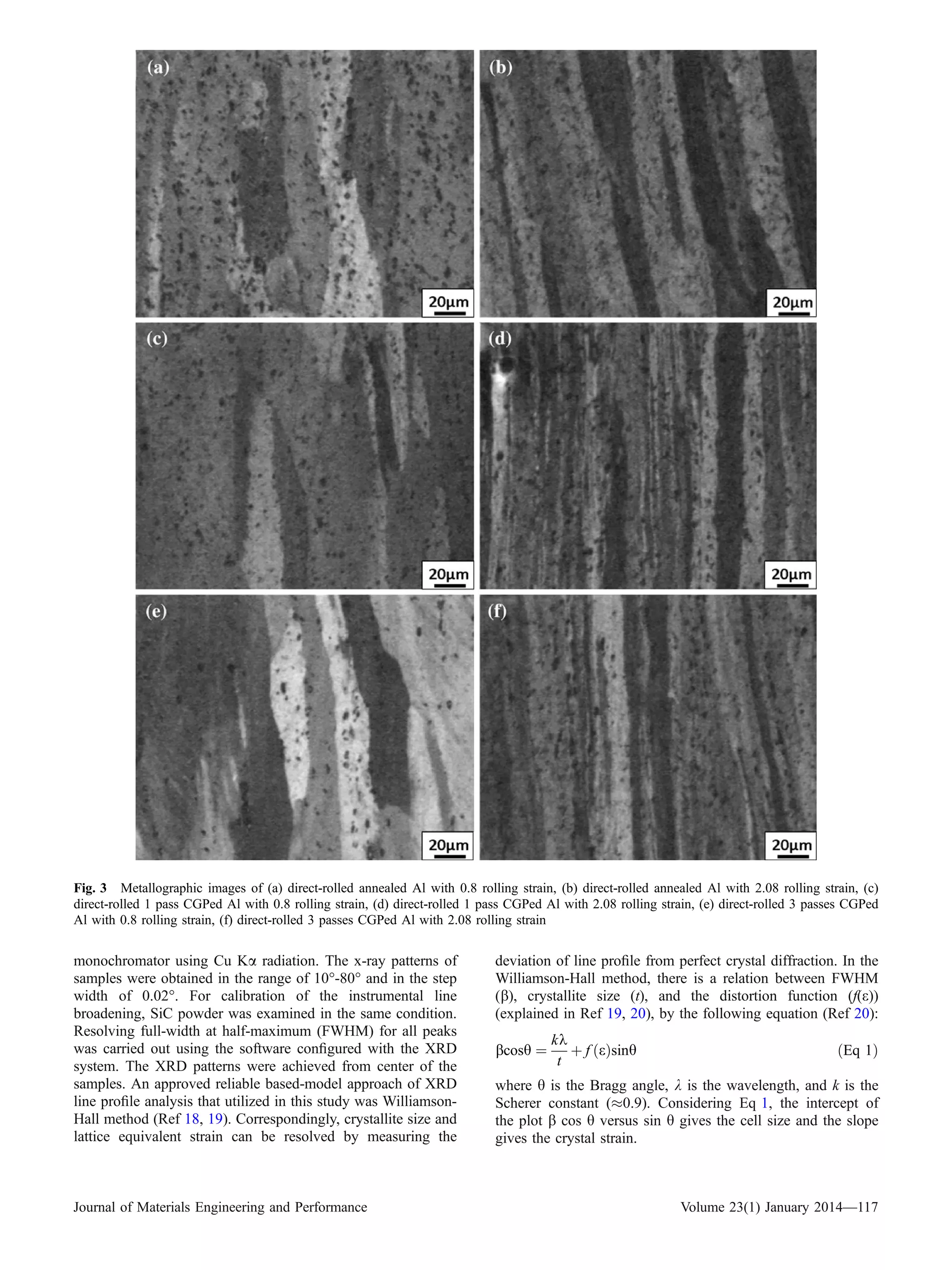

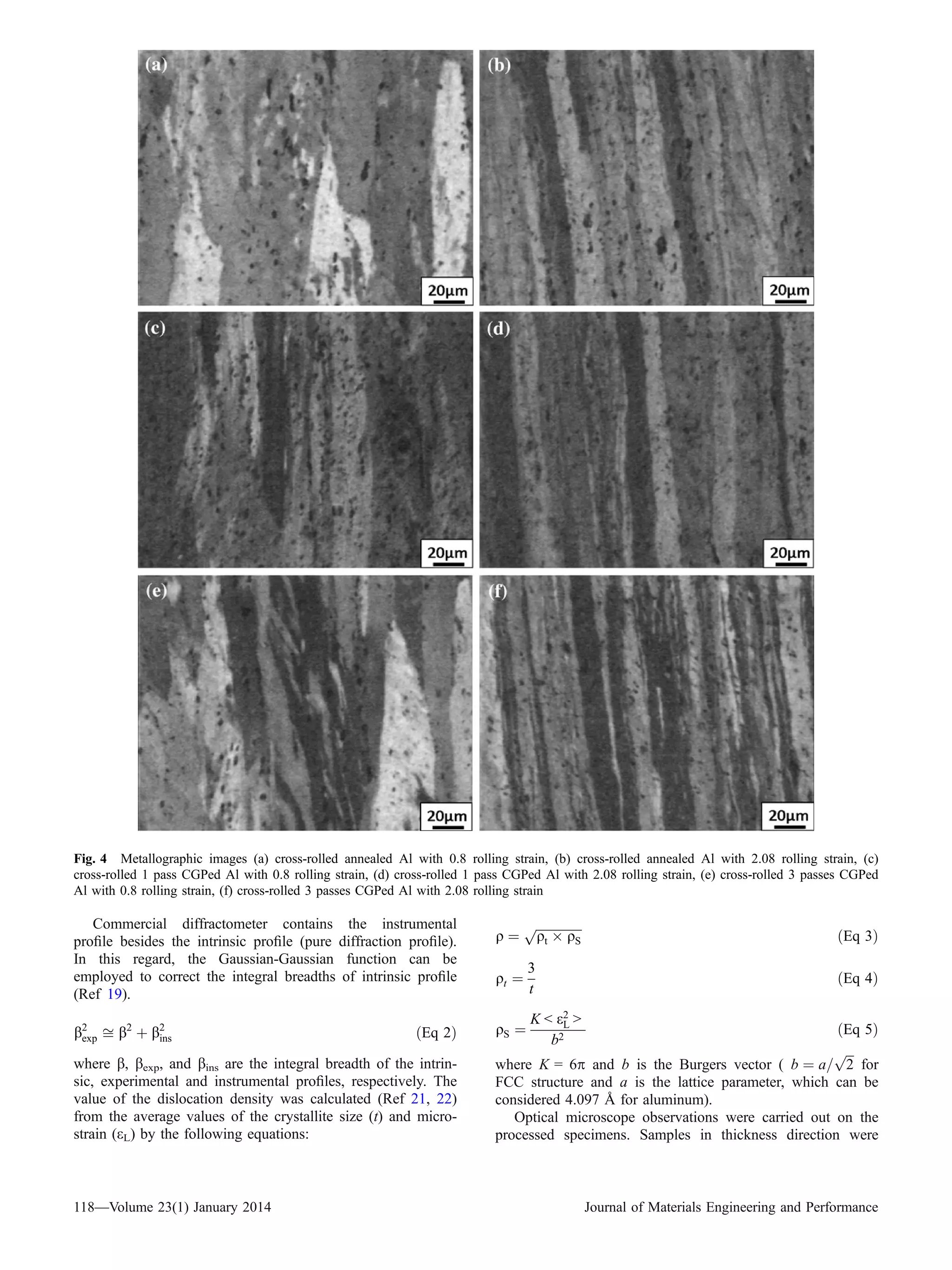

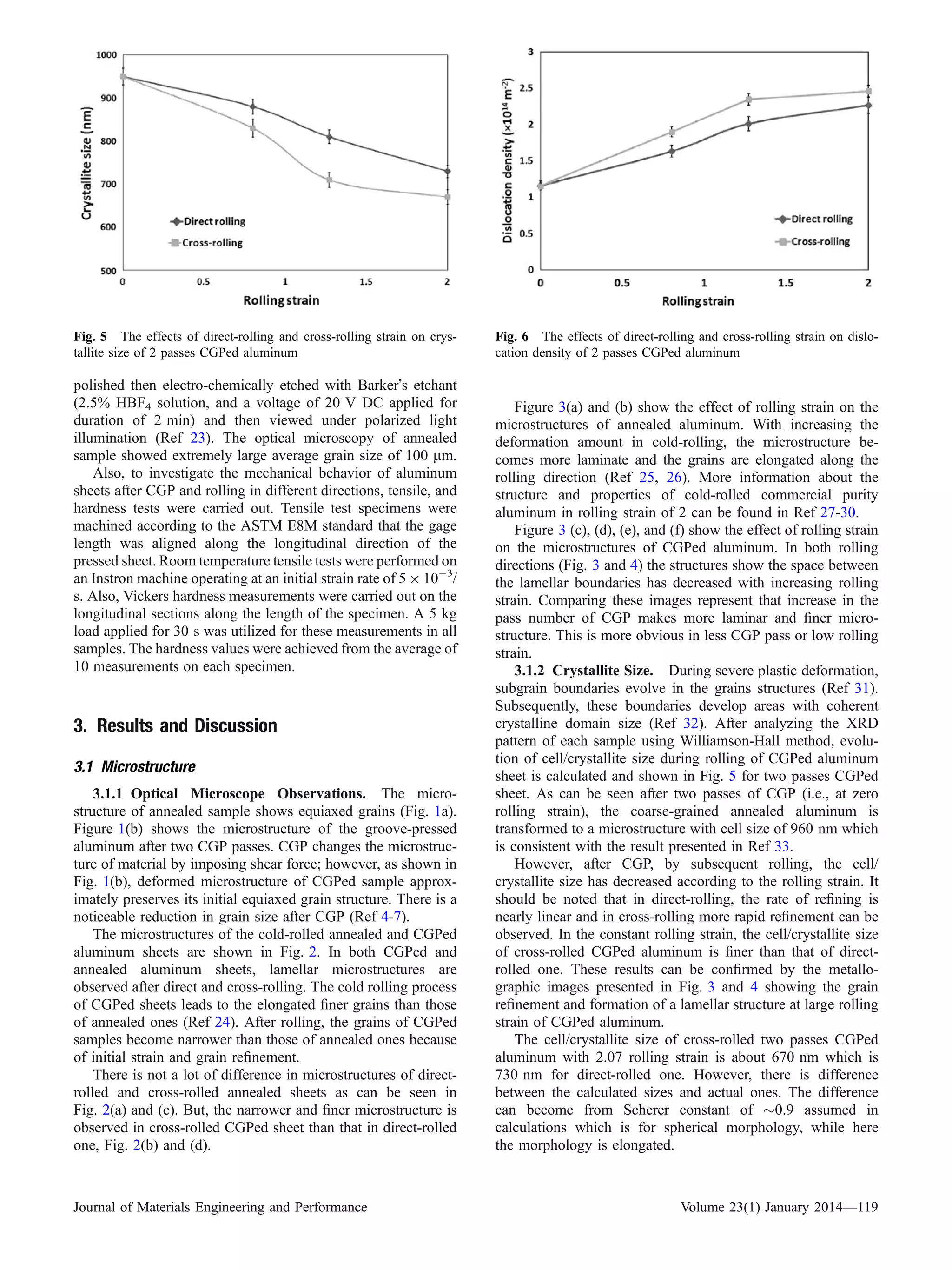

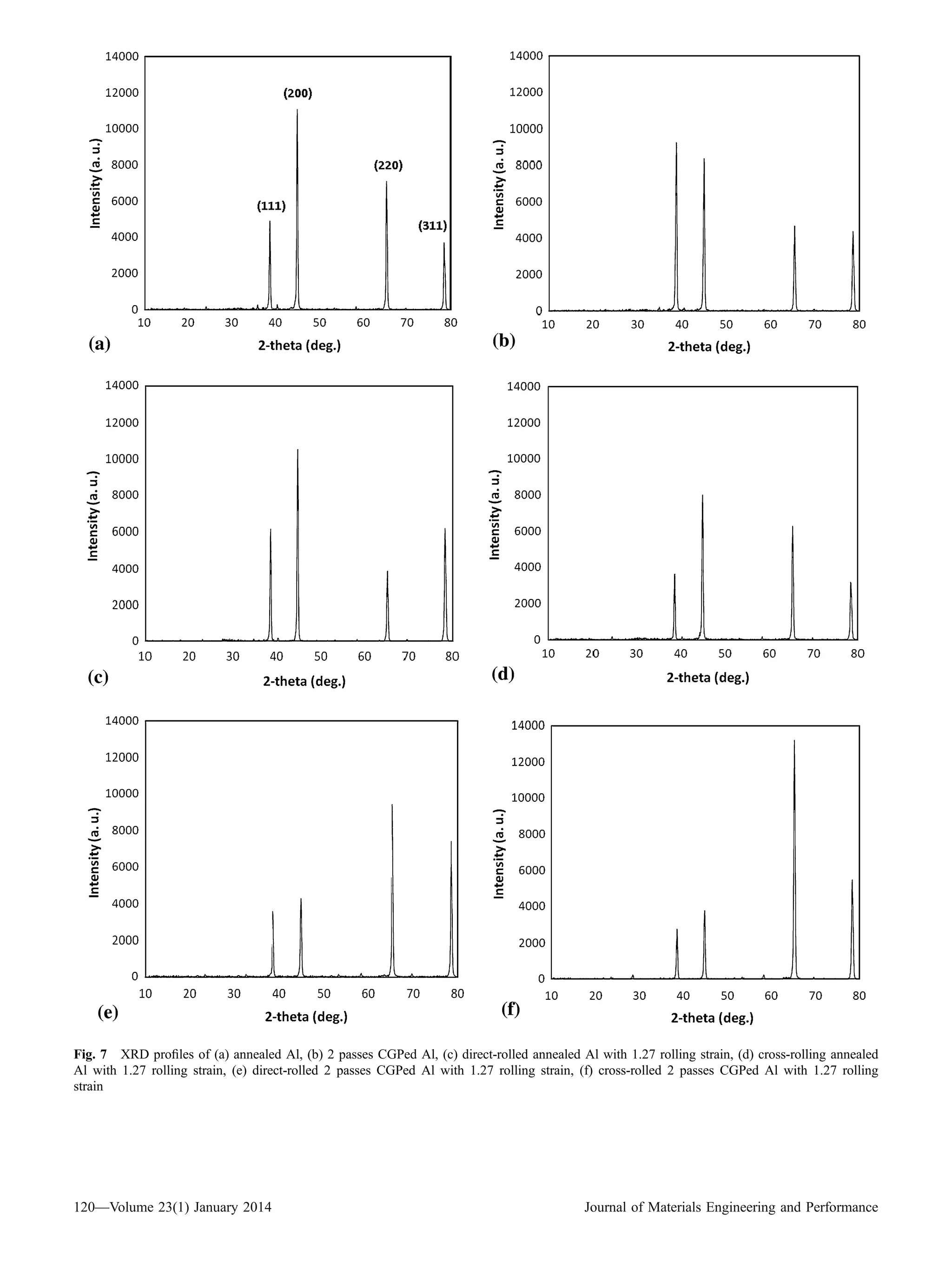

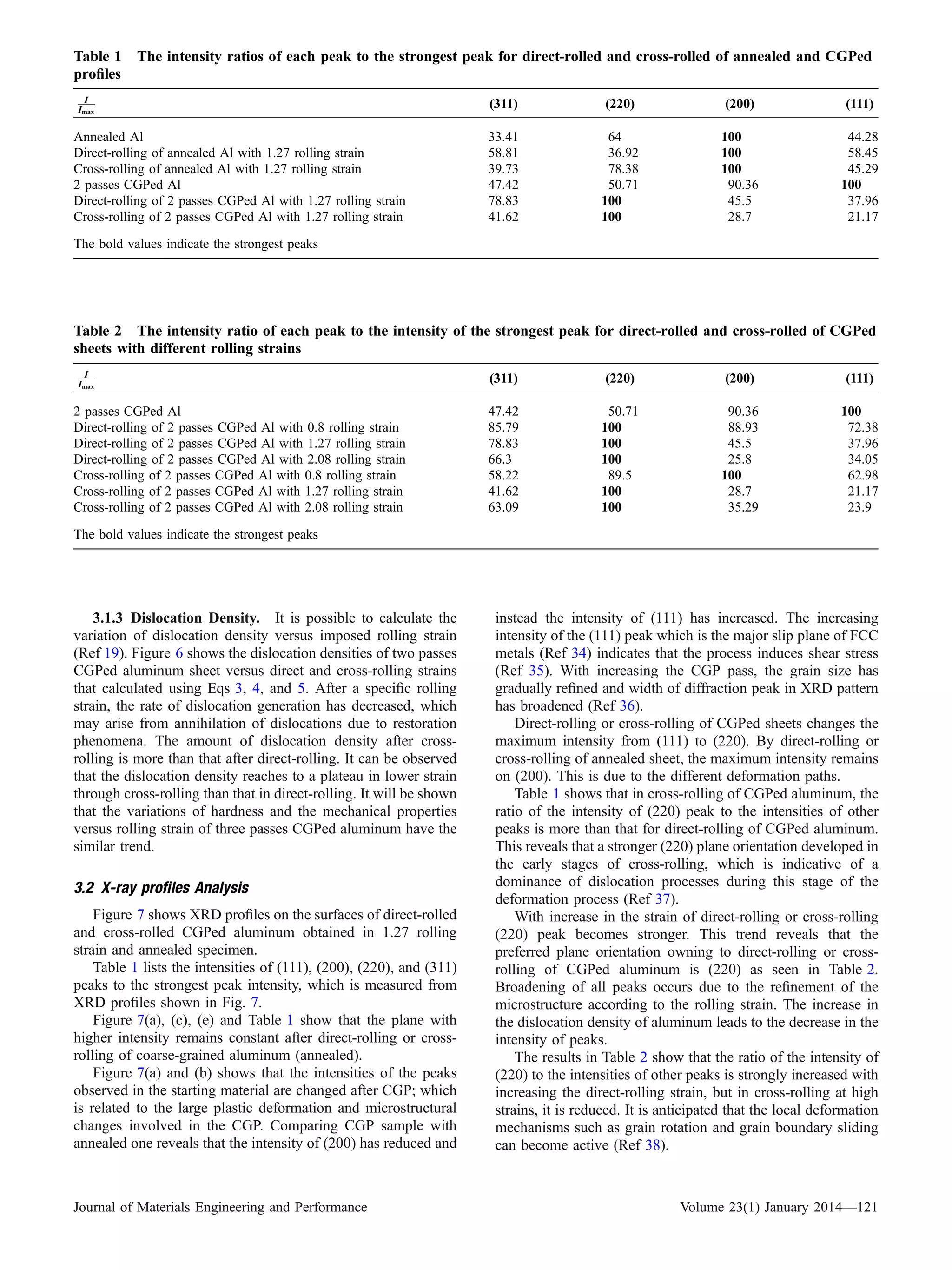

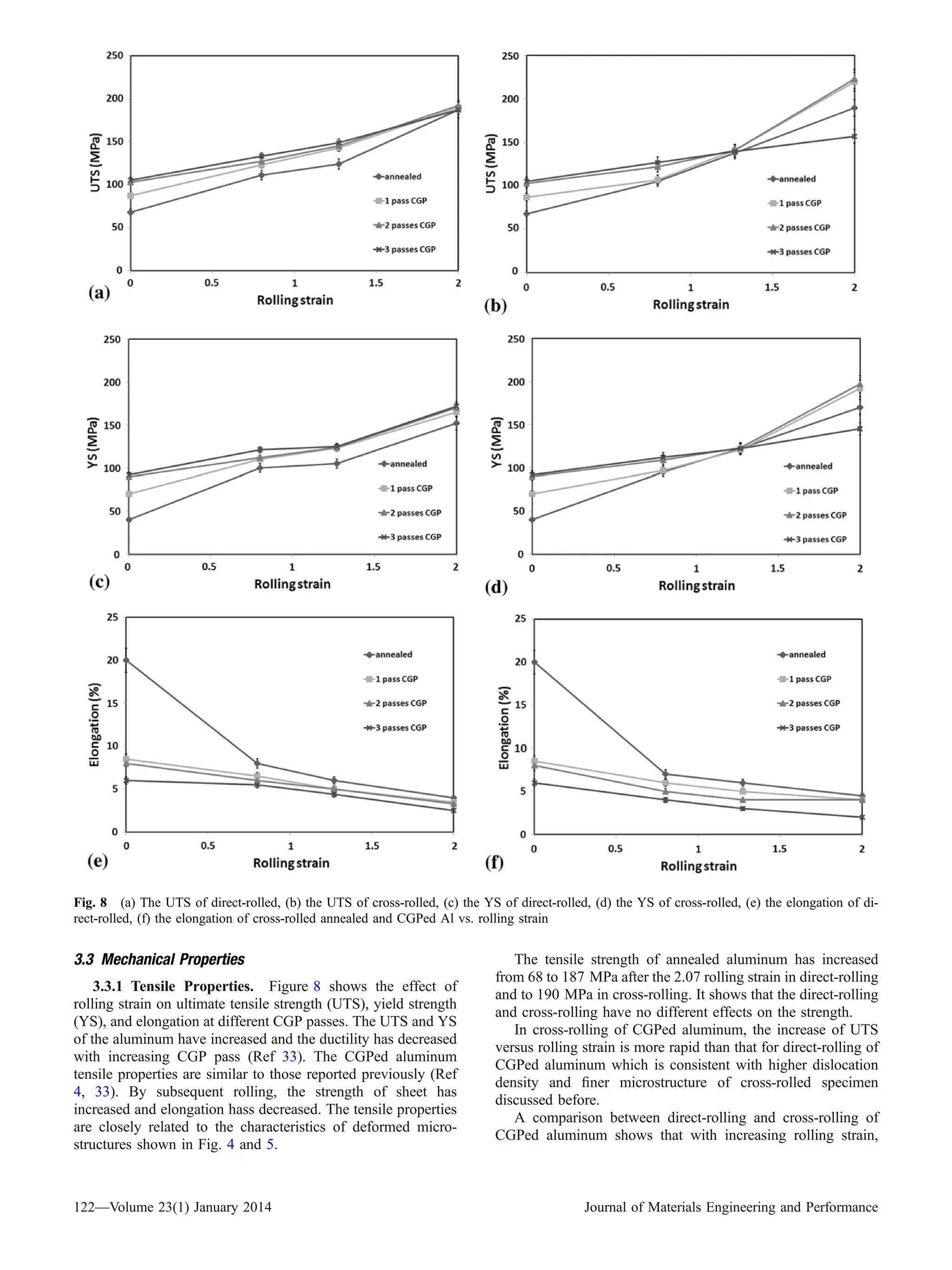

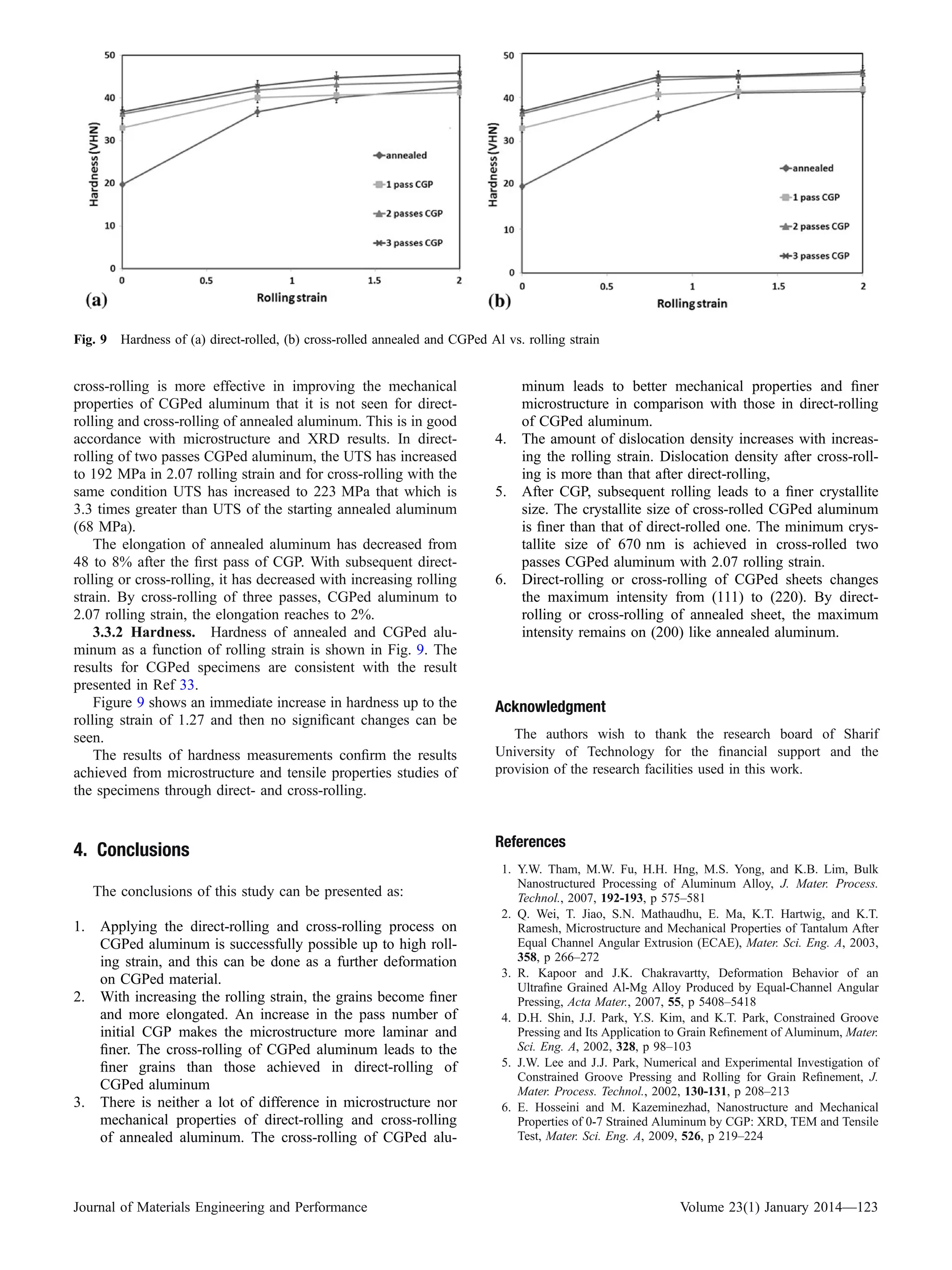

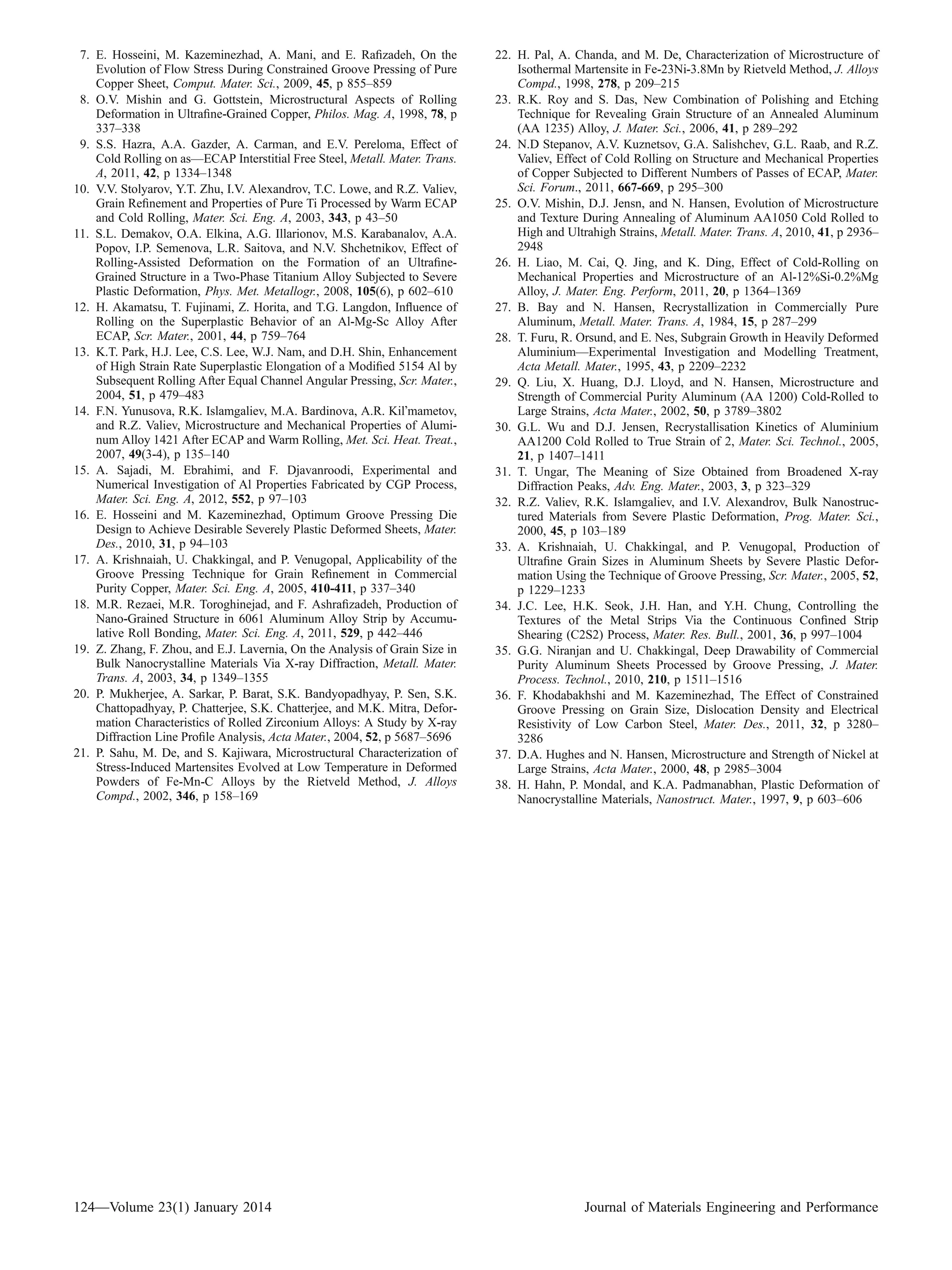

The study investigates the effects of direct and cross-rolling on the mechanical properties and microstructure of severely deformed aluminum sheets processed by constrained groove pressing. Results indicate that cross-rolling is more effective in enhancing mechanical properties and producing finer grains compared to direct-rolling, with notable changes in the crystallite size and dislocation density. This research aims to better understand the correlation between the processing techniques and material properties in aluminum sheets post severe plastic deformation.