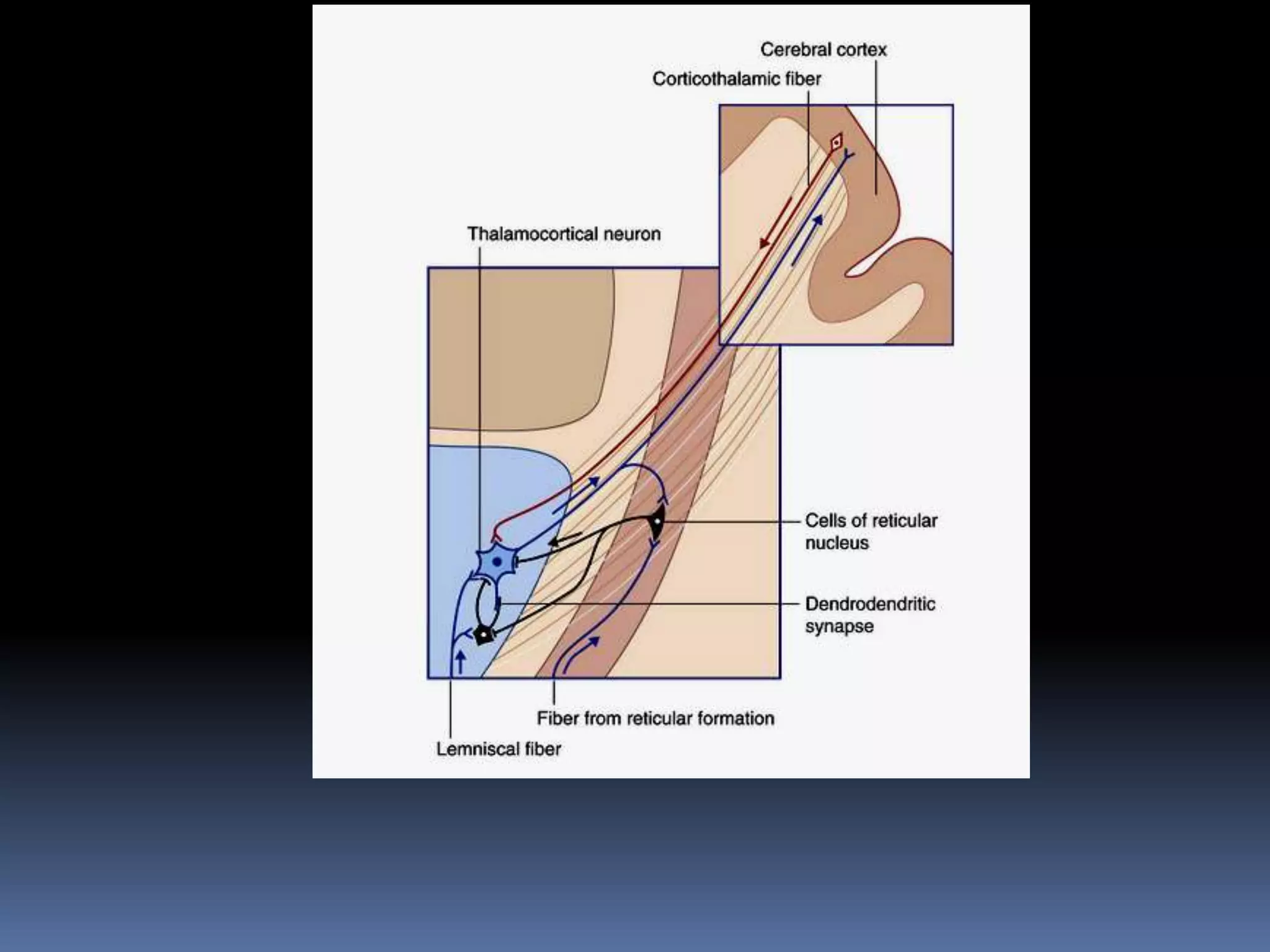

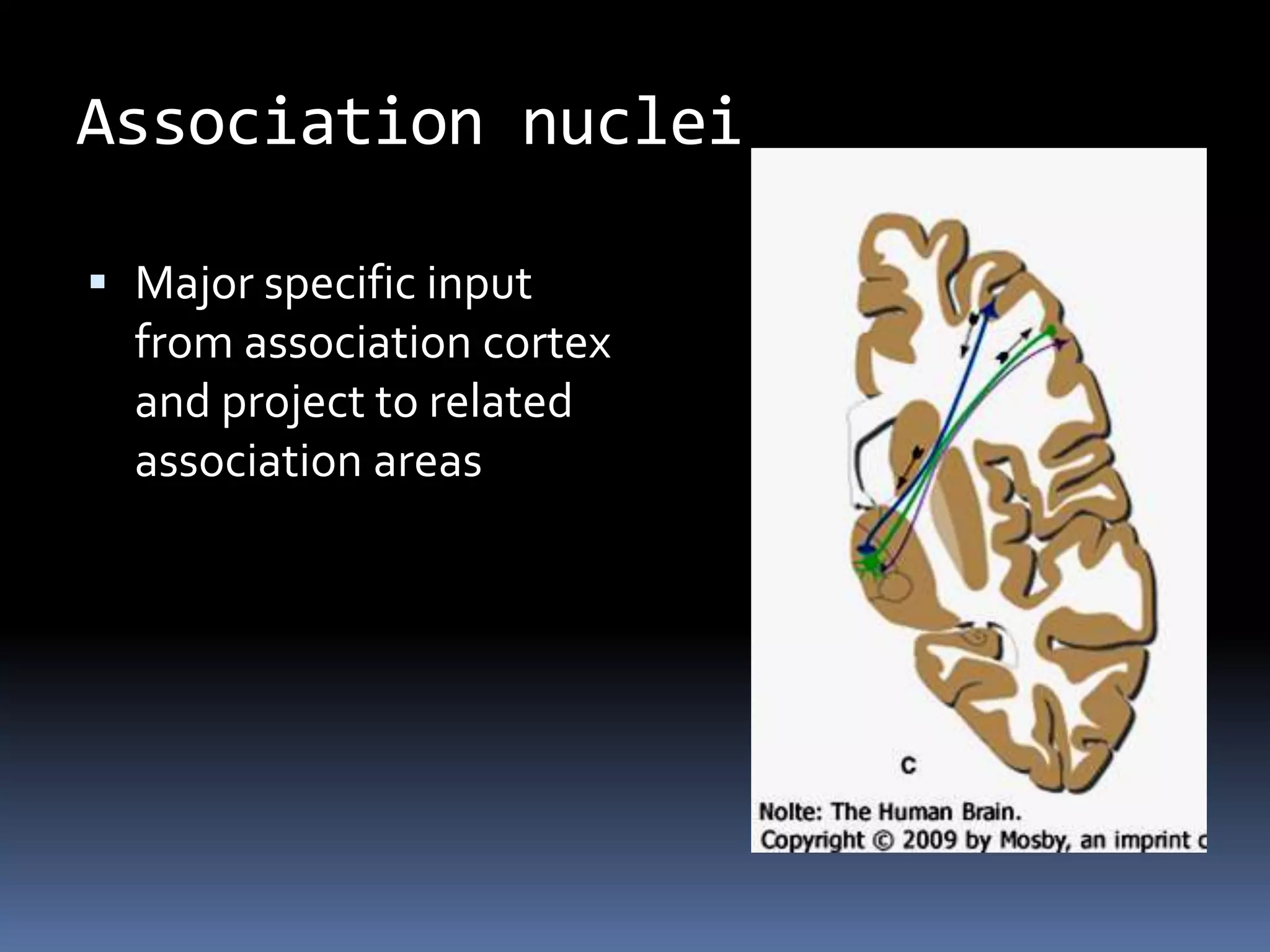

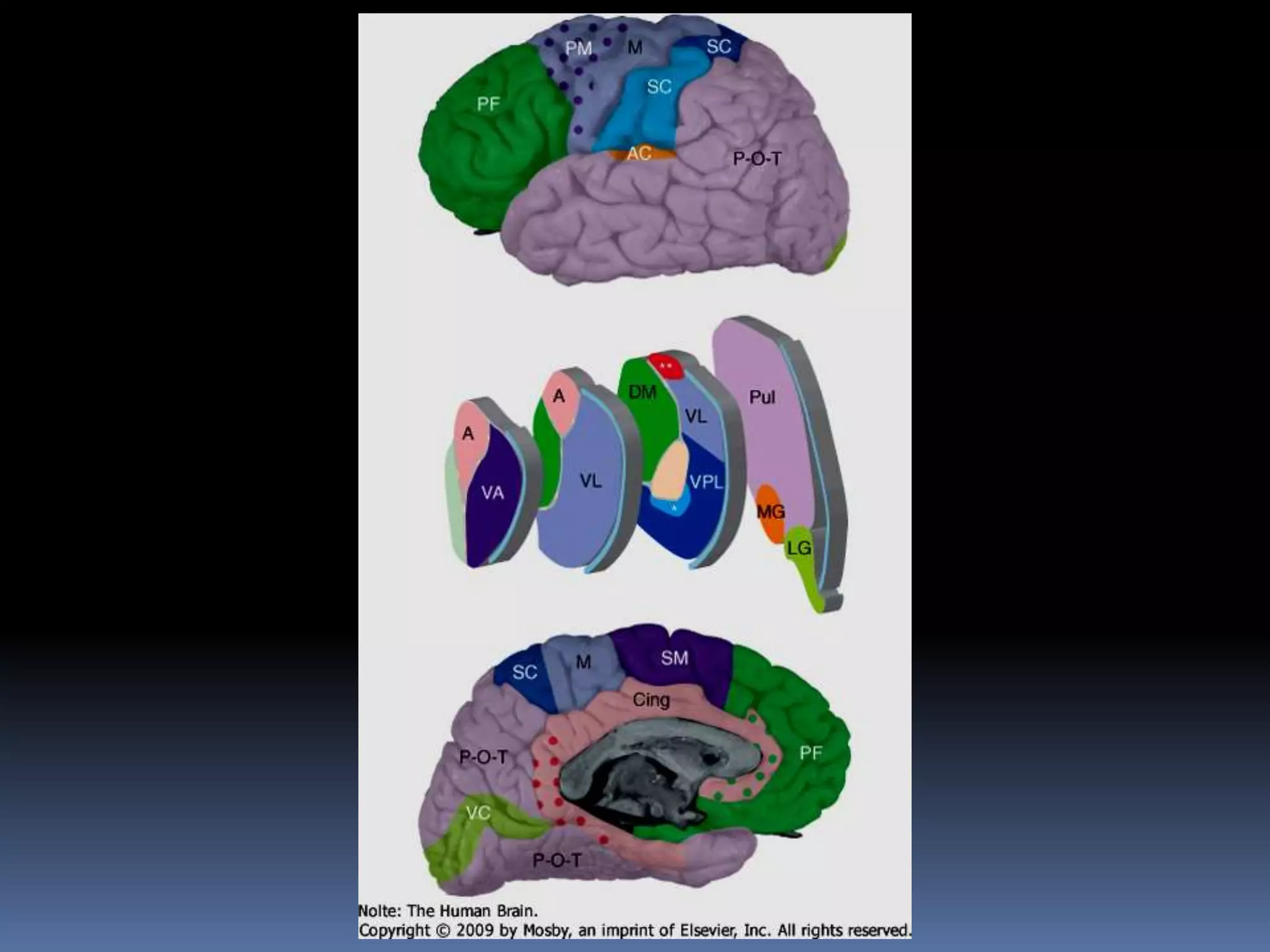

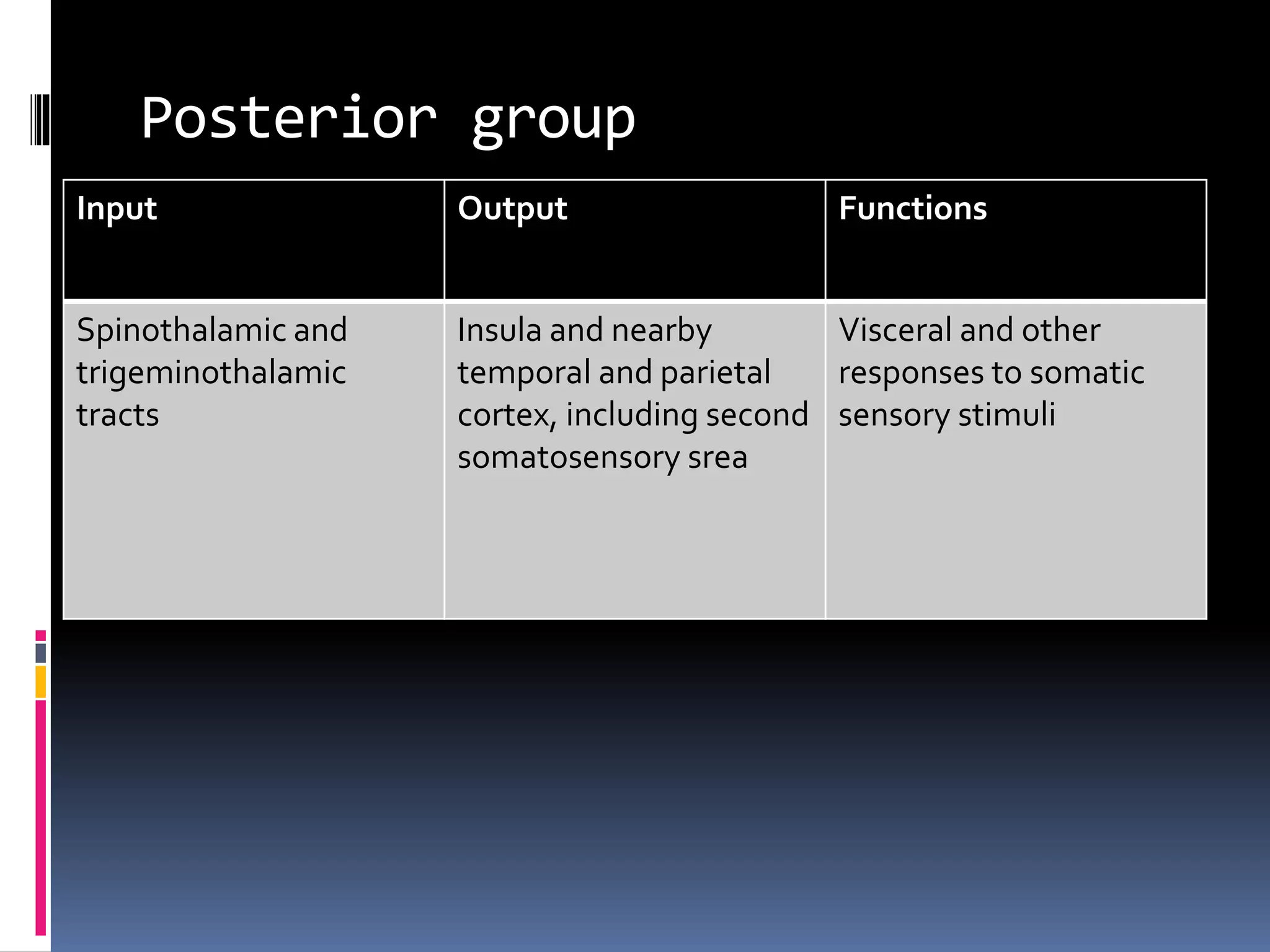

The thalamus acts as a relay center and gatekeeper for sensory and motor information between subcortical structures and the cerebral cortex. It is divided into nuclear groups based on inputs and outputs. Relay/specific nuclei receive defined inputs and project to specific cortical areas, transmitting information like touch, sound and vision. Association nuclei connect association areas and are involved in higher-level processing. Nonspecific nuclei like the intralaminar and reticular nuclei project widely and regulate arousal and cortical activity. Damage to posterior thalamic areas can cause thalamic syndrome with abnormal sensory experiences and central pain.

![Nuclei of ventral tier

Ventral anterior, ventral lateral- concerned

with motor control; are connected to basal

nuclei and cerebellum

Ventral posterior is subdivided into ventral

posterolateral[ smatosensory input from

body] and ventral posteromedial

[somatosensory input from head]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-22-2048.jpg)

![Midline nuclei

Rostral continuation of periaqueductal gray

matter

Form interthalamic adhesion [when present]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-26-2048.jpg)

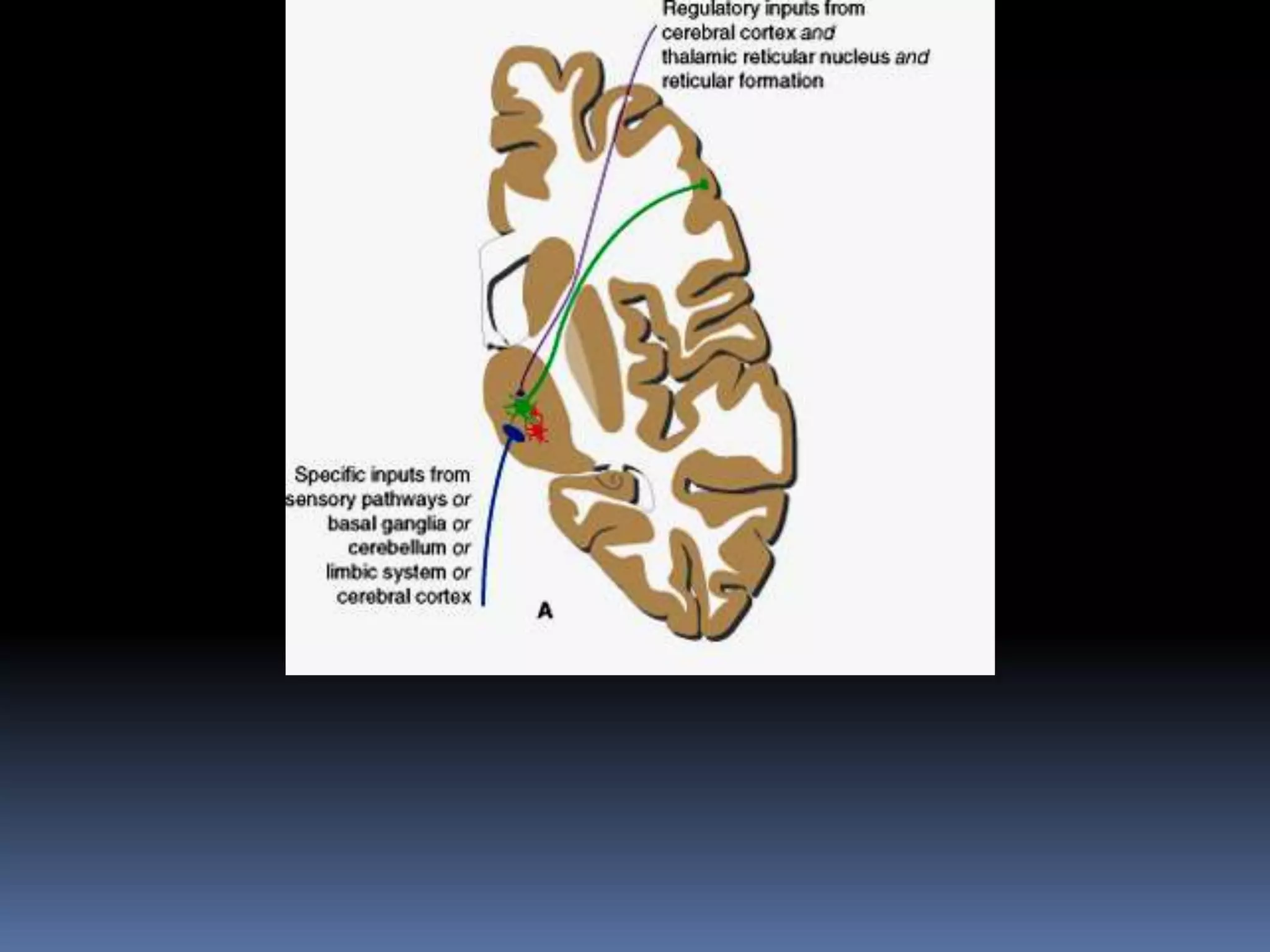

![Inputs

Specific - Regulatory

Specific inputs convey information that a

given nucleus may pass to cerebral cortex

[and for some nuclei to additional sites].

Examples; Medial lemniscus specifically to

VPL. Optic tract to LGB](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-28-2048.jpg)

![Relay/specific nuclei

Specific inputs from

subcortical areas[e.g.

medial lemniscus]-

project to a well

defined area of

cerebral cortex](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-49-2048.jpg)

![Ventral anterior

Input Output Functions

Pallidum [globus

pallidus]

Frontal lobe,

including premotor

and supplementary

motor areas

Motor planning and

more complex

behavior](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-51-2048.jpg)

![Ventral lateral [anterior

division]

Input Output Functions

Pallidum [globus

pallidus]

Premotor and

supplementary

motor areas

Planning

commands to be

sent to motor

neurons](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-52-2048.jpg)

![Ventral lateral [posterior

division]

Input Output Functions

Contralateral

cerebellar nuclei

Primary motor area Cerebellar

modulation of

commands sent to

motor neurons](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-53-2048.jpg)

![Ventral posterolateral

Input Output Functions

Medial lemniscus,

spinal lemniscus

Primary

somatosensory area

Somatic sensation

[principal pathway,

from contralateral

body below head]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-54-2048.jpg)

![Ventral posteromedial

Input Output Functions

Contralateral

trigeminal sensory

nuclei

Primary

somatosensory area

Somatic sensation

[principal pathway,

from contralateral

half of head: face,

mouth, larynx,

pharynx, dura

mater]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-55-2048.jpg)

![Medial geniculate body

Input Output Functions

Inferior colliculus Primary auditory

cortex

Auditory pathway

[from both ears]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-56-2048.jpg)

![Lateral geniculate body

Input Output Functions

Ipsilateral halves of

both retinas

Primary visual

cortex

Visual pathway

[from contralateral

visual fields]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-57-2048.jpg)

![Lateral dorsal

Input Output Functions

Hippocampal

formation,

pretectal

area,superior

colliculus

Cingulate

gyrus,Parietal,

temporal, and

association

cortex[visual

cortex]

Interpretation of

visual stimuli;

memory](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-60-2048.jpg)

![Intralaminar and midline

nuclei/nonspecific

Specific inputs[basal

nuclei or limbic

structures] and ptoject

to cerebral cortex,

basal nuclei, limbic

structures](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-63-2048.jpg)

![Intralaminar nuclei

Input Output Functions

Cholinergic and

central nuclei of

reticular

formation,locus

coeruleus, collateral

branches from

spinothalamic tracts,

cerebellar nuclei,

pallidum

Extensive cortical

projections, especially

to frontal and parietal

lobes; striatum

Stimulation of cerebral

cortex in waking state

and arousal from

sleep;somatic

sensation, especially

pain [from

contralateral head

and body]; control of

movement](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-64-2048.jpg)

![THALAMIC SYNDROME[DEJERINE-ROUSSY SYNDROME]

Damage more or less restricted to the

posterior thalamus can cause a characteristic

type of dysesthesia that is somewhat similar

to trigeminal neuralgia

paroxysms of intense pain may be triggered

by somatosensory stimuli.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bsgug6gltyiyjrbb0spt-thalamus-2-230505154223-2bed9a87/75/Thalamus_2-ppt-71-2048.jpg)