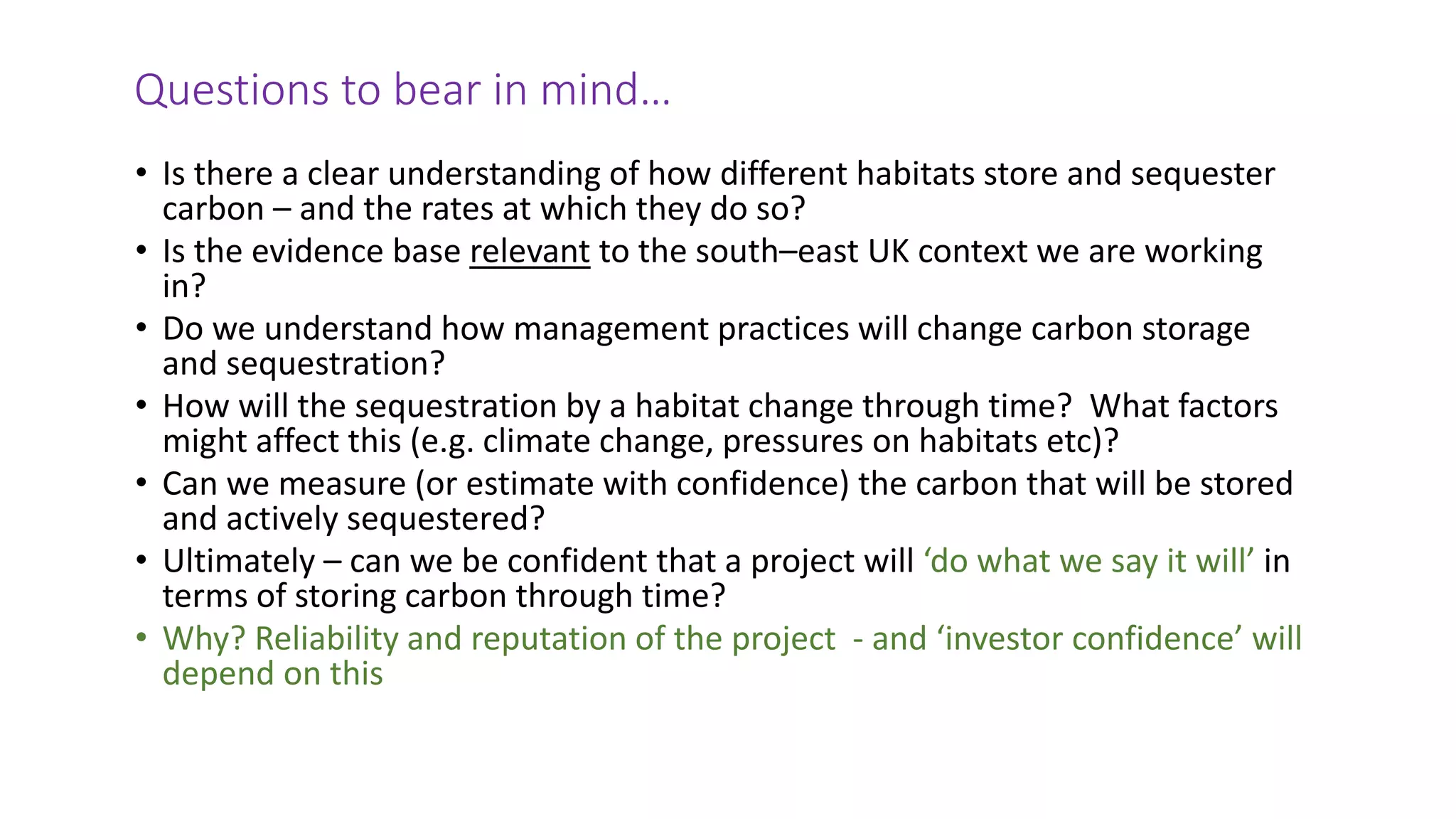

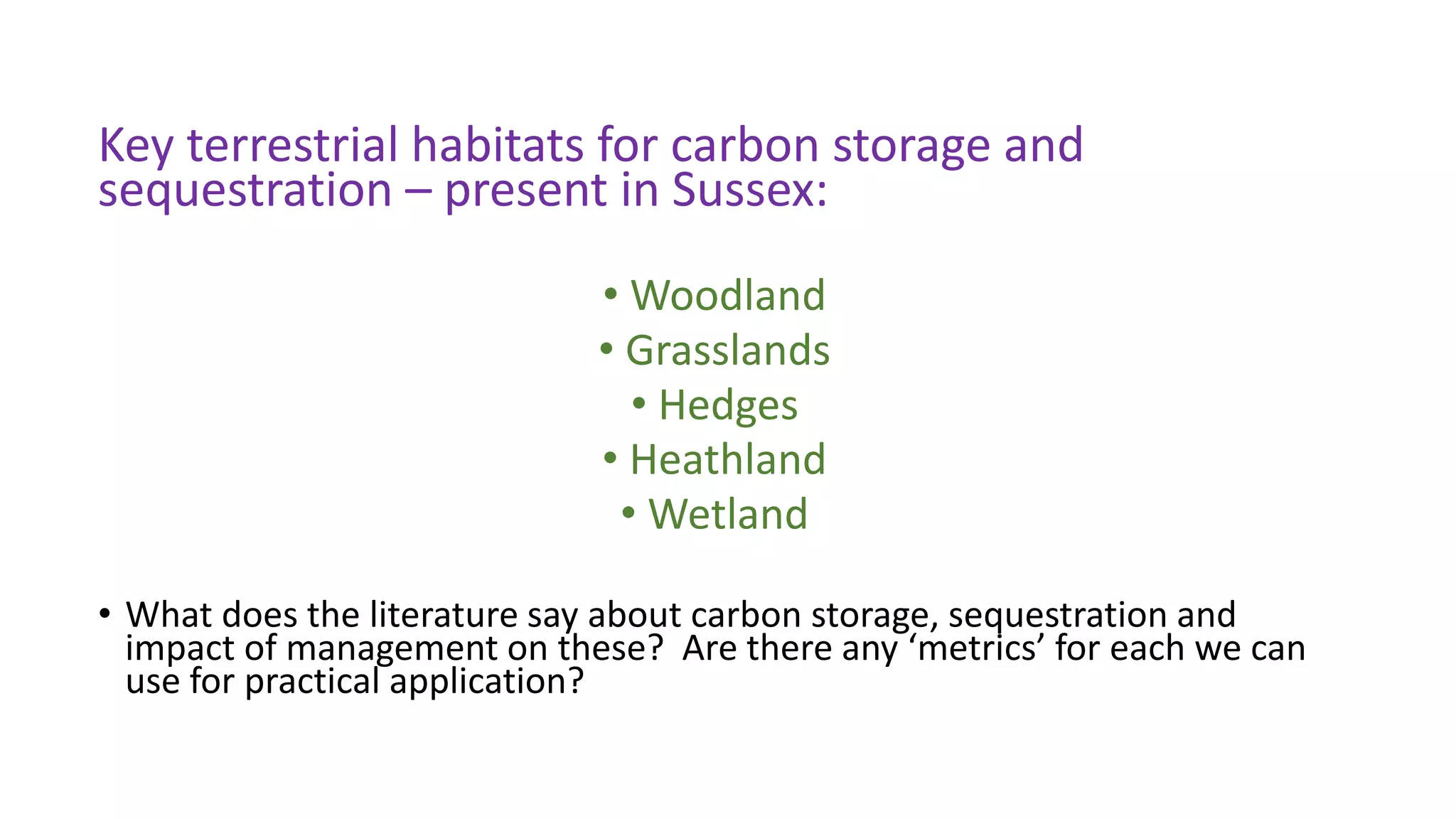

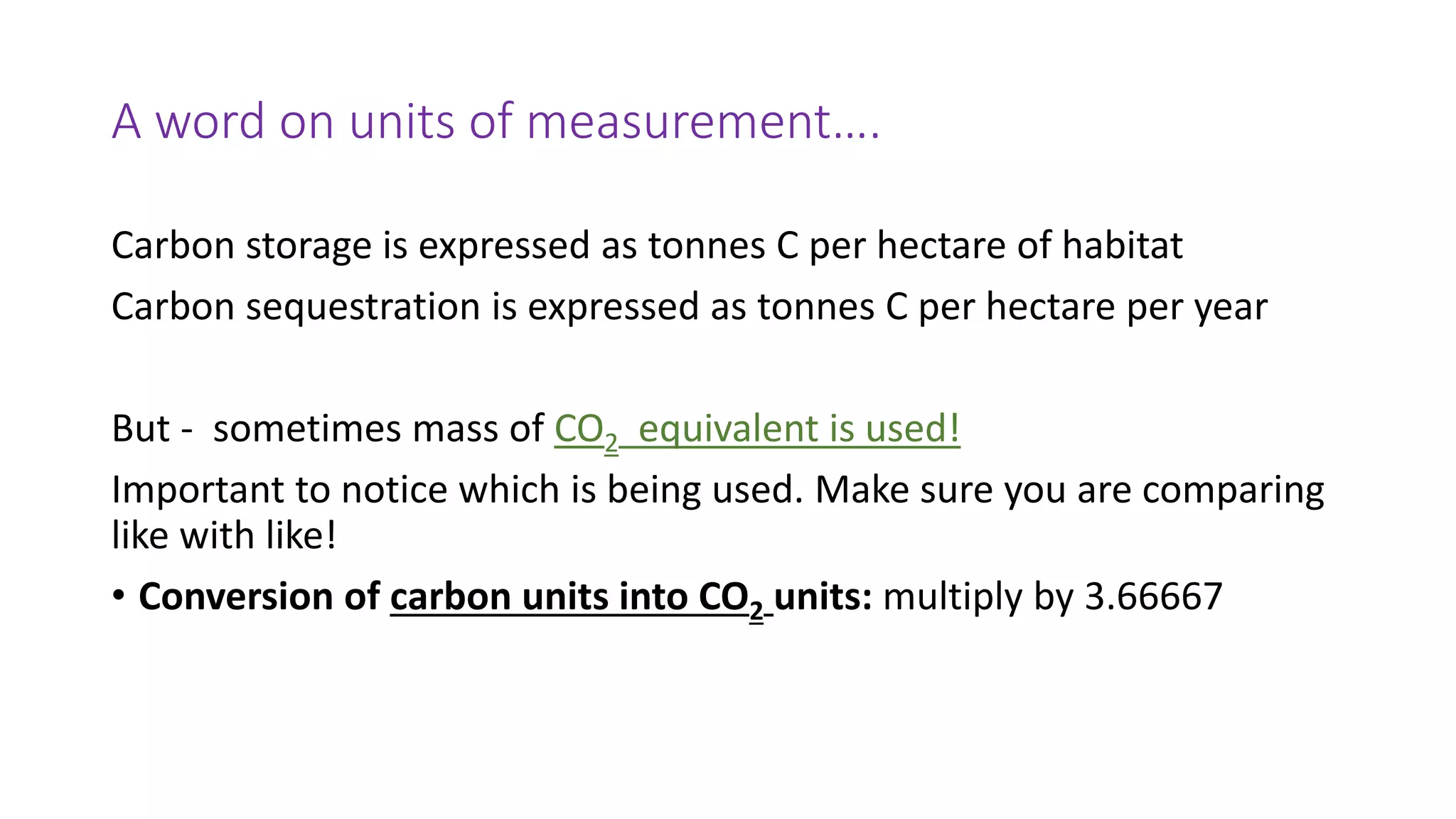

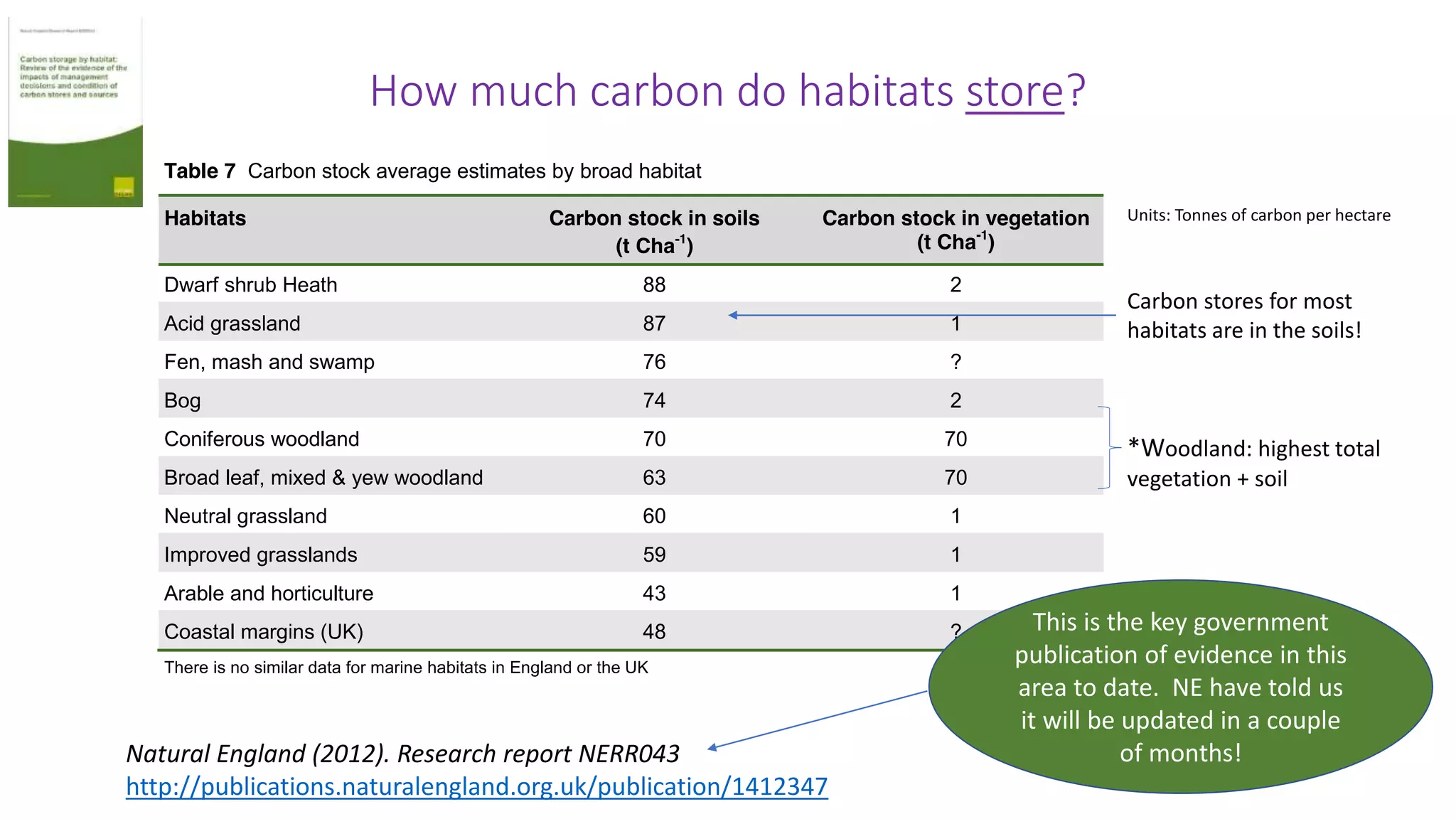

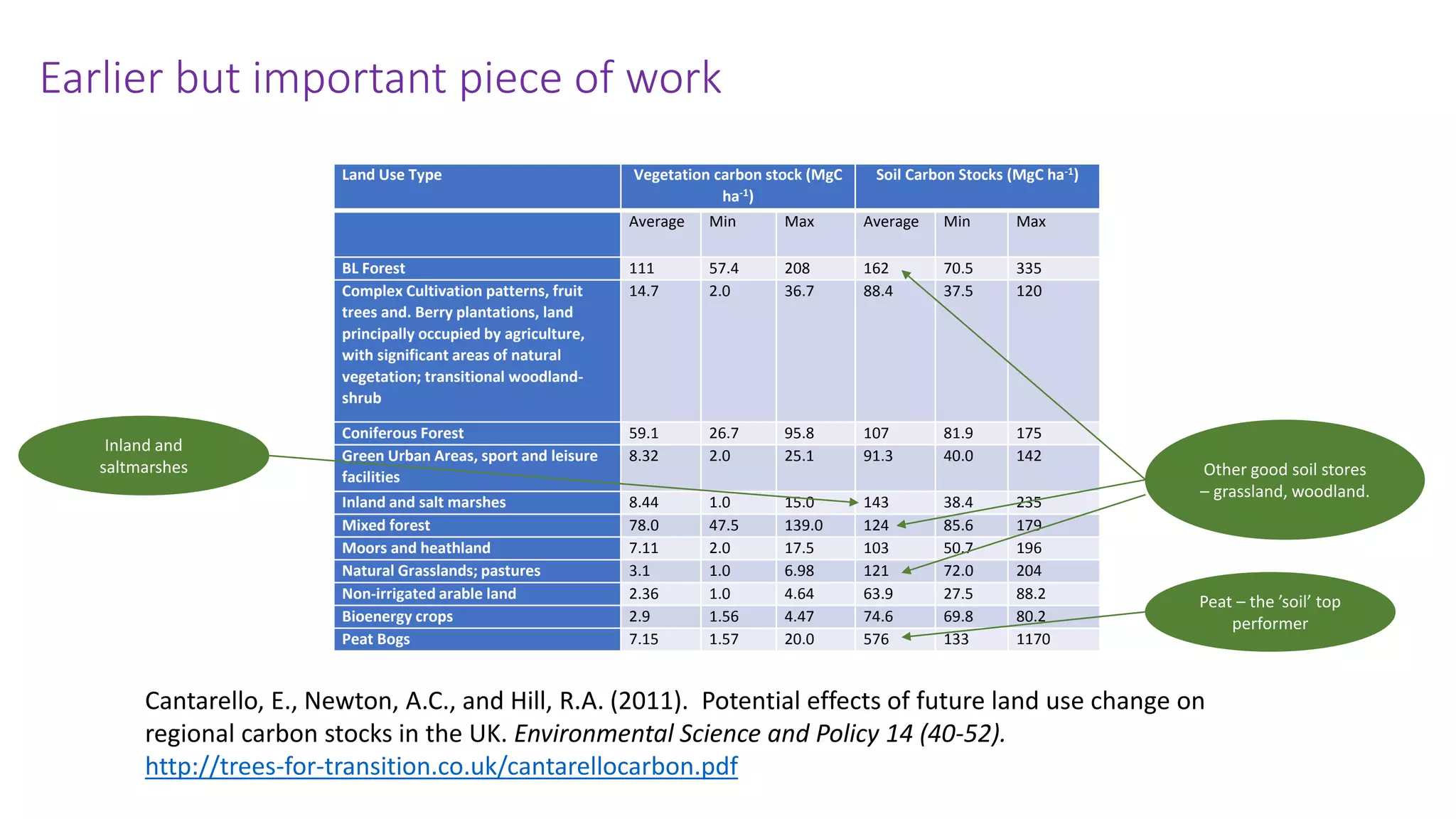

The document provides an overview of what is known about carbon storage and sequestration in various UK terrestrial habitats. It notes that the evidence base is still developing and varies in certainty between habitat types. Key points made include:

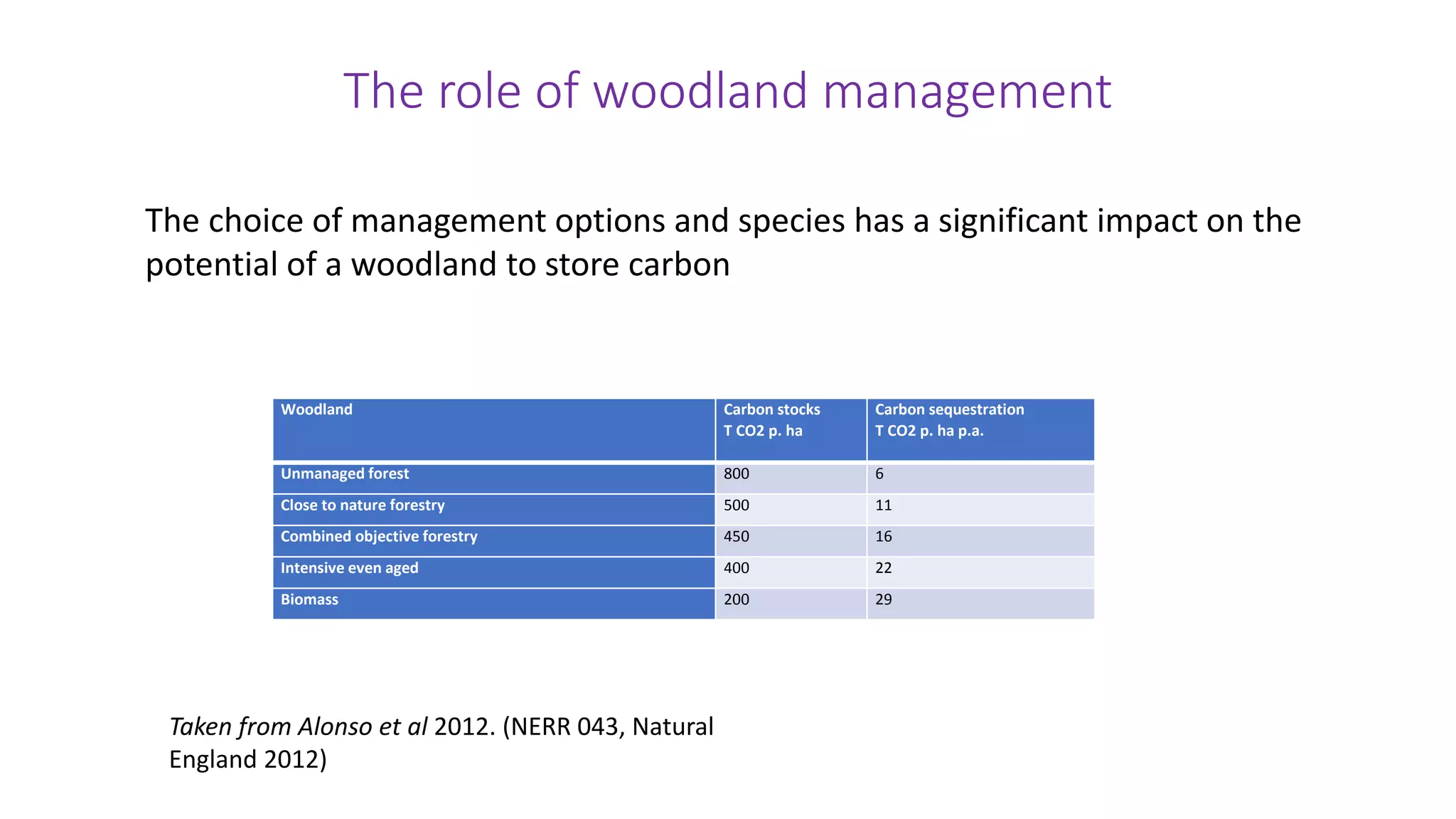

- Woodlands and peatlands store the most carbon, primarily in soils. New woodland creation and restoration of degraded habitats can sequester carbon.

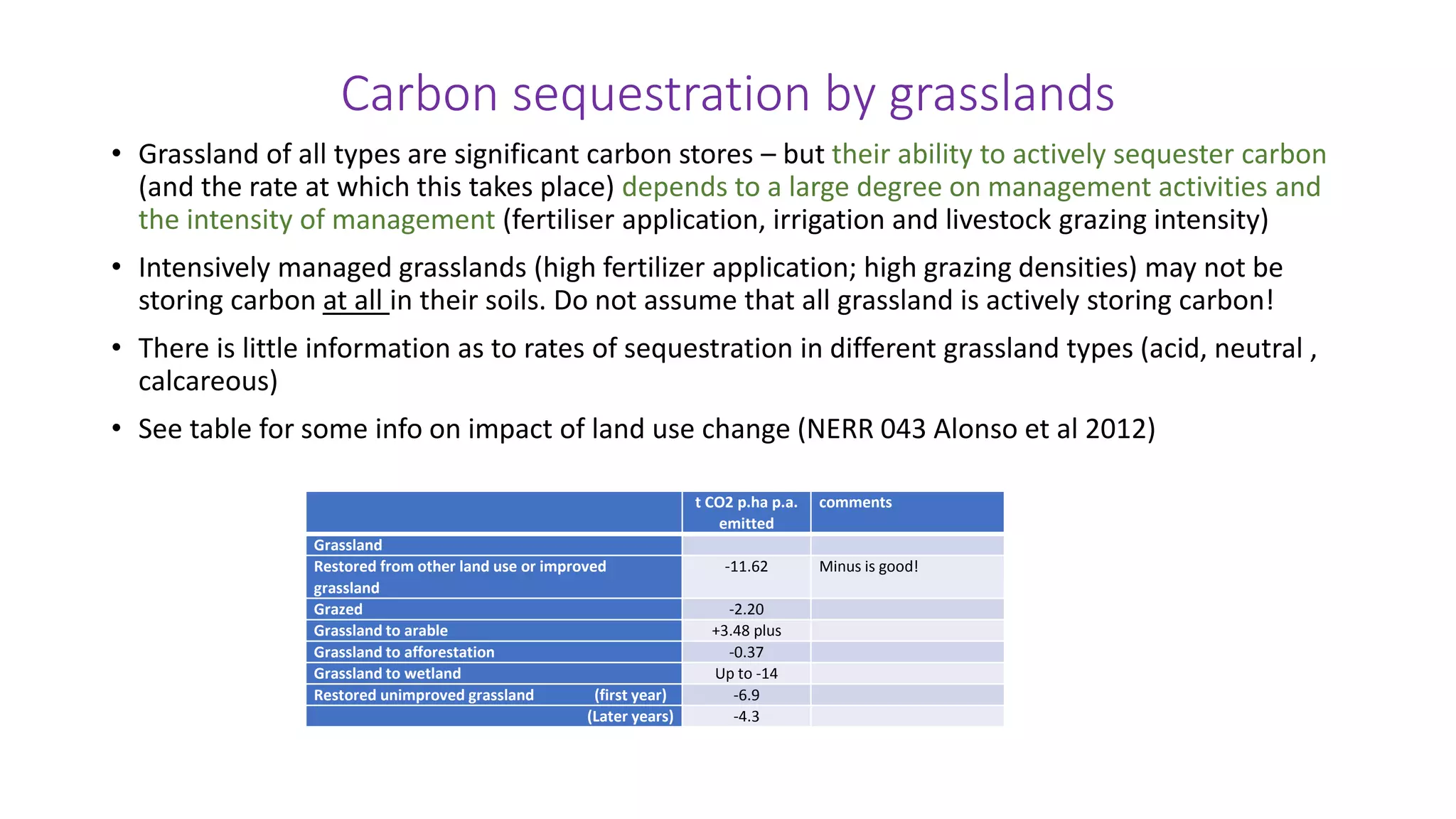

- Grasslands are also significant carbon stores, though intensive management may reduce soil carbon. Reducing grazing and soil disturbance helps sequestration.

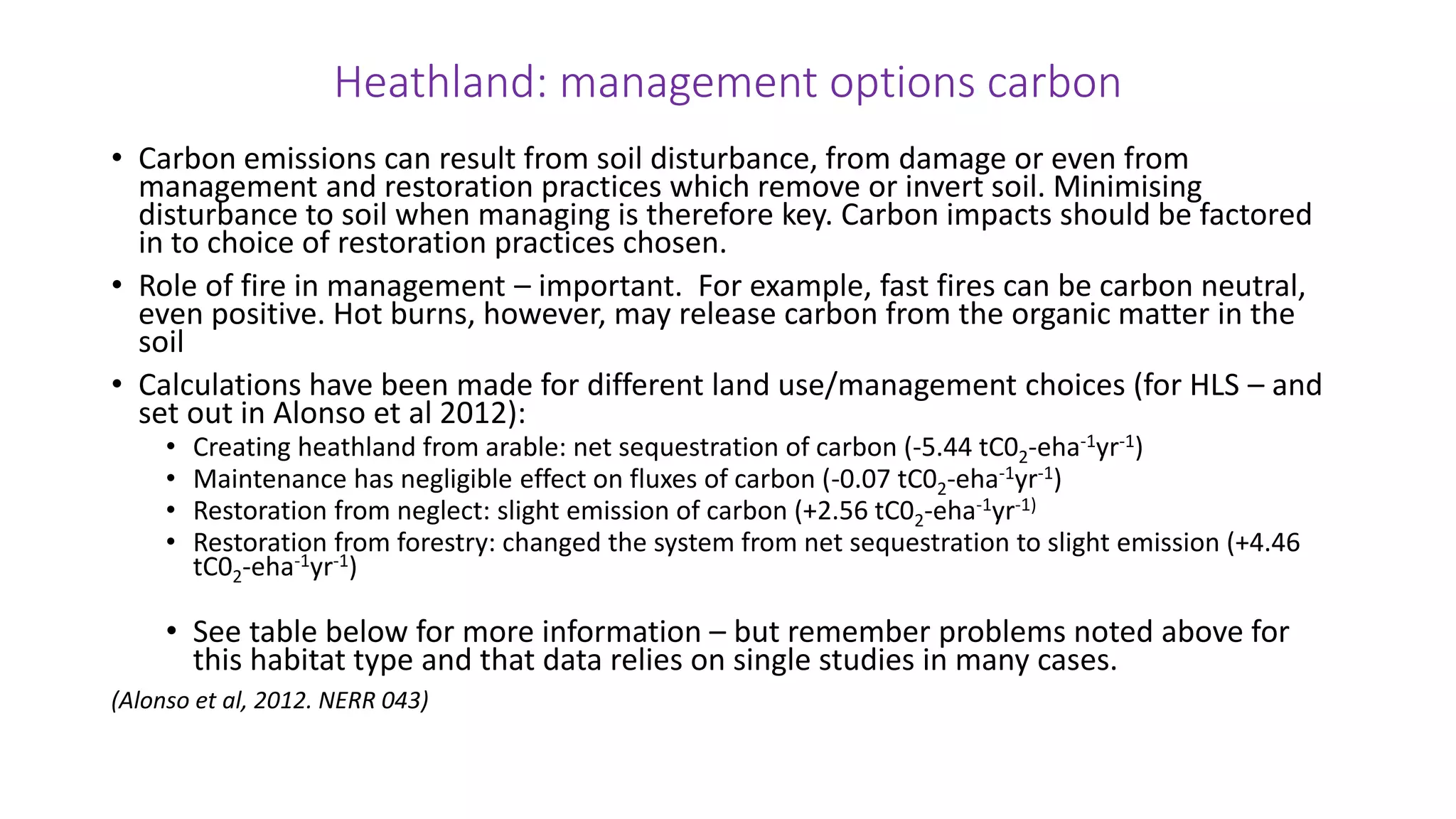

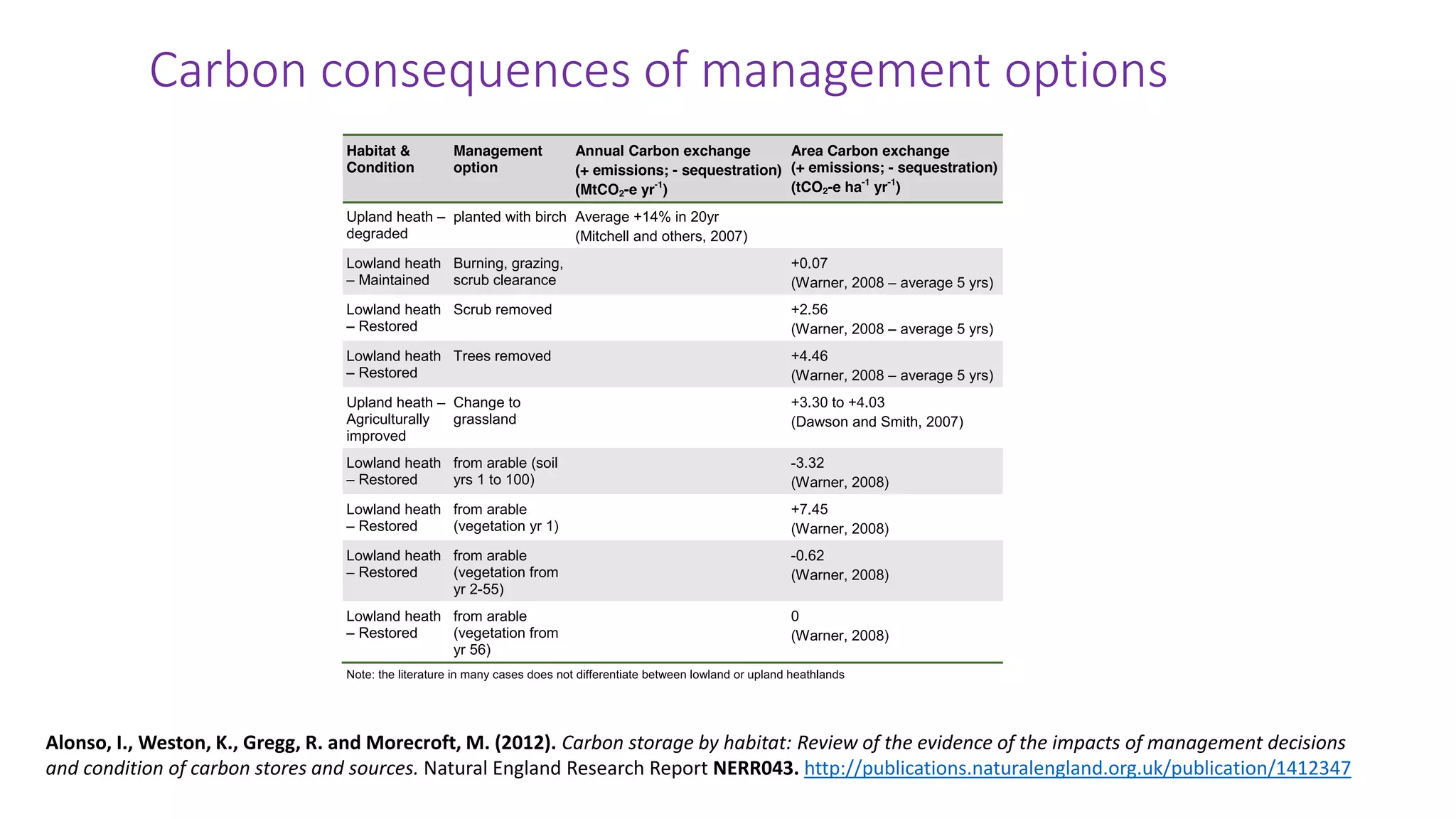

- Heathlands store carbon in soils, especially wet heathlands. Management practices should minimize soil disturbance to avoid carbon emissions.

- Further research is still needed to better quantify carbon metrics

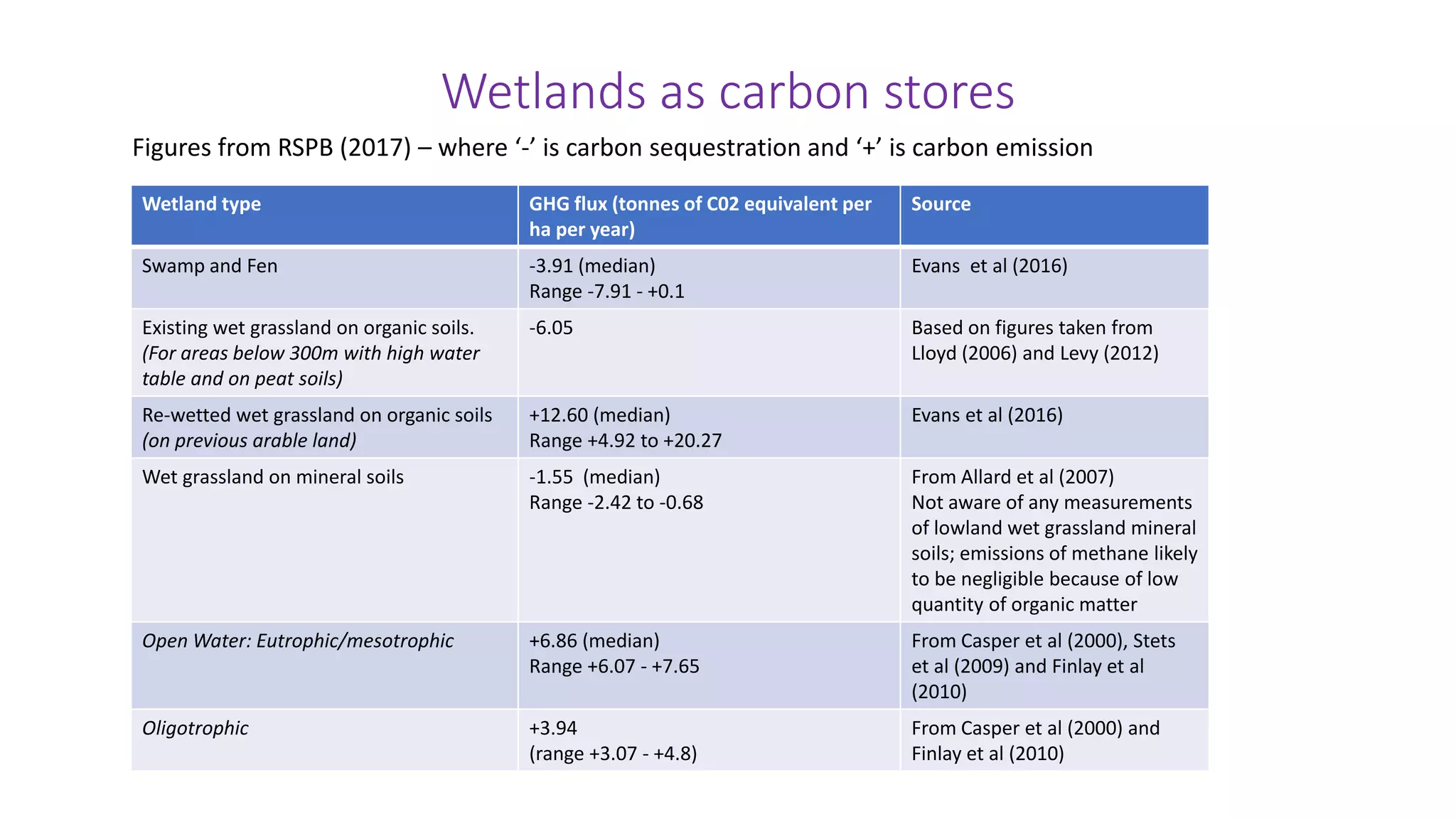

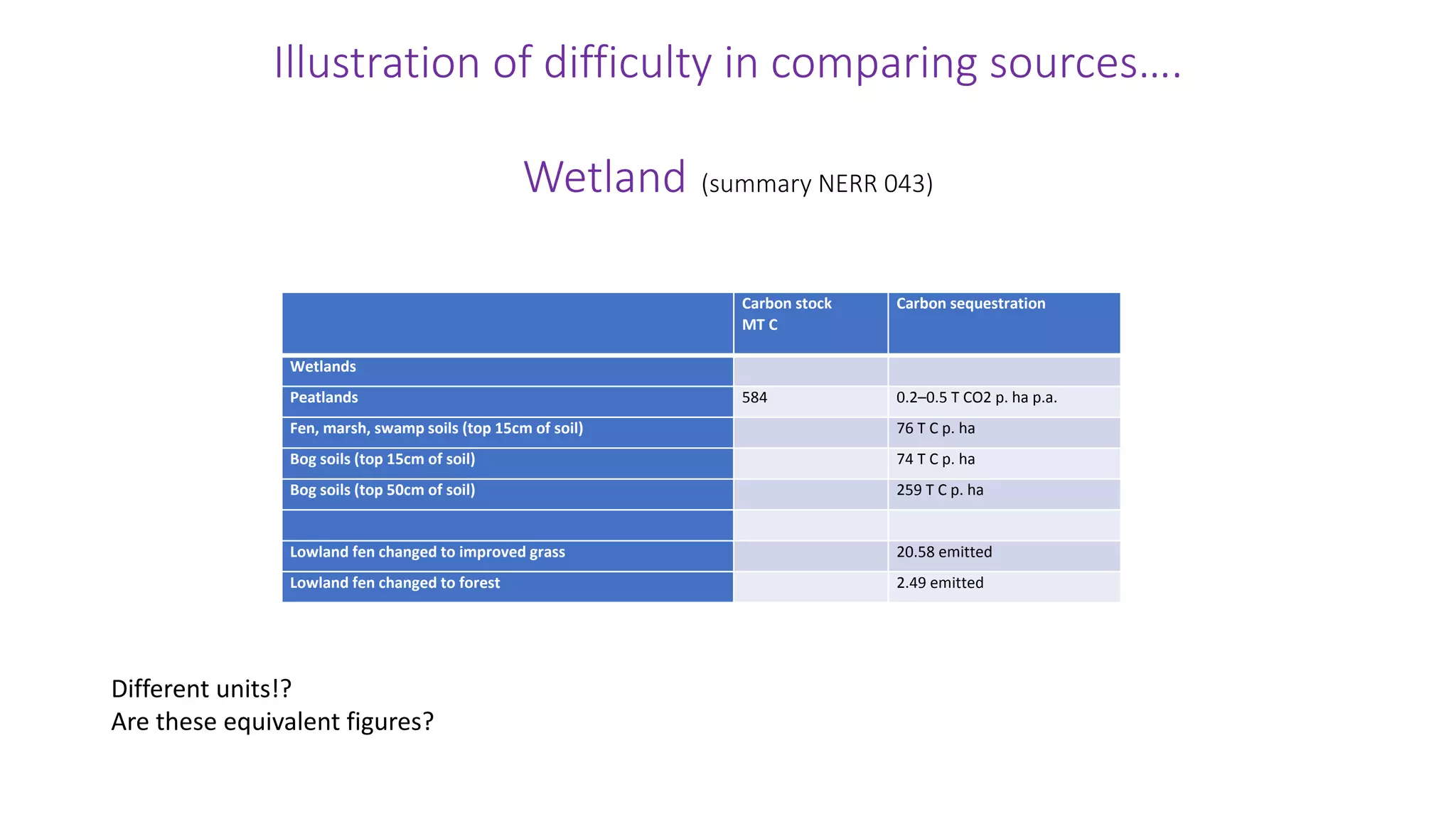

![Wetland destruction and restoration

Key points about wetlands and carbon….

• Land use change from wetlands to other habitat tends to result in net carbon loss (emission)

• Drainage and disturbance causes changes to carbon cycling, decomposition and fluxes

• Damaged wetlands can be restored – and this does increase carbon sequestration

• This does not compensate for net accumulation of carbon in original system before disturbance

• Thus wetland protection is preferential to restoration

Confidence in metrics – low:

• Wetlands act as ‘transitions’ between terrestrial and aquatic systems.

• Understanding carbon ‘fluxes’ – very difficult

• Much more research needed to understand carbon balance of England’s varied wetland habitats

[Source Alonso et al 2012, NERR 043]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01terrestrialhabitatsandcarbonweb-200630155846/75/Terrestrial-habitats-and-carbon-web-28-2048.jpg)