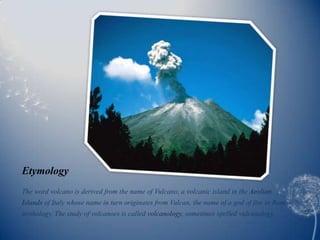

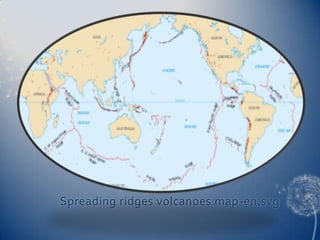

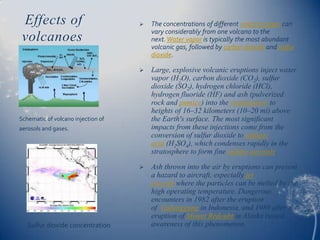

Volcanoes form at plate boundaries where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. Eruptions occur when magma from below Earth's surface reaches the surface through the volcano. Major eruptions can inject sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere which cools the climate and causes famines. The largest volcanoes are stratovolcanoes, also called composite volcanoes, which are conical mountains built up by layers of hardened lava and ash.