This document is Matthew Chacko's teaching portfolio. It includes his teaching philosophy, which emphasizes developing students' critical thinking skills through examining issues of social inequity and power dynamics related to race, gender, class, and sexuality. He uses techniques like "notice-and-focus" close reading to have students analyze texts in detail. His courses also aim to foster empathy and awareness of societal issues. Chacko structures his classes with a combination of lecture, discussion, and individual guidance. He scaffolds assignments to help students write a culminating thesis-driven paper and uses heuristics to develop good writing habits like synthesis. The portfolio includes details of Chacko's teaching experience, curriculum, lesson plans, and student evaluations.

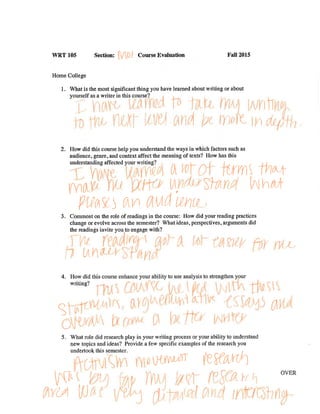

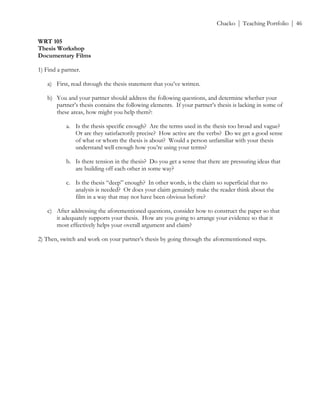

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 20

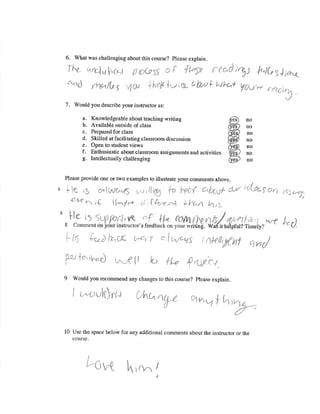

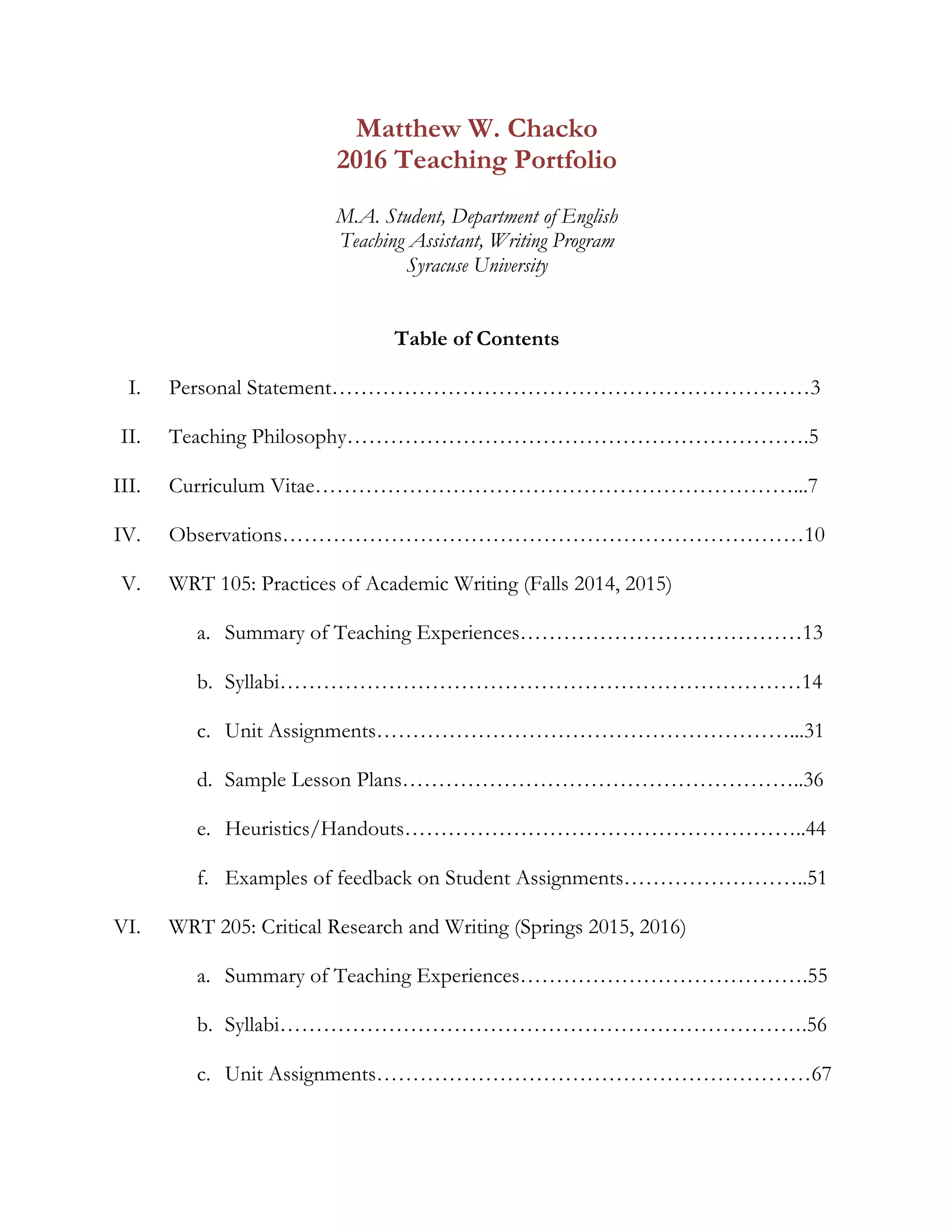

Mon,

22 Sept

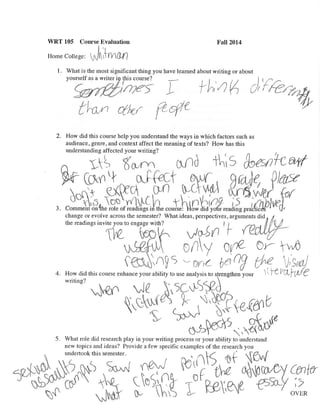

Read Pages 209-218 (Intro and Zemliansky) and pages 244-250 (Sturken & Cartwright) in chapter 5 of EaT.

On the Bb discussion thread: Write a post in which you revise or expand your initial ideas about visual

literacy in light of our work in class and the two essays in Everything’s a Text. Work with a flashpoint or

flashpoints!

Watch the film trailers for the following films (Who Killed Vincent Chin, Let the Fire Burn, Incident at Oglala, Three

Broken Cameras, Paris is Burning) and give me a list of your top 3 films in class on Wednesday.

Review two handouts under the unit 2 tab on Bb: “Analytical Moves” (only pp 14-18) and “Viewing

Documentary Films” and make sure you have them available in class.

Finish your Unit 1 Reflection prompt.

Wed,

24 Sept

Read and annotate Mark Strand’s “The Loneliness Factor” (pp. 257-260 in EaT). [the three Hopper

paintings Strand analyzes are in the chapter 5 glossy insert]

Respond to questions #4 and #5 on page 261. Choose one of the responses and post it to the Bb discussion

thread.

Watch your assigned film, and take good notes being mindful of the visual literacy concepts we have

explored so far.

Sun,

28 Sept

Special Event: 7:00 pm in Kittredge Auditorium: Documentary Film Analysis Workshop

Mon,

29 Sept

Upload your film trailer to your blog and in the same post analyze the rhetorical structure of the trailer:

i.e. how does the trailer attempt to persuade its viewers to go see the film? How does the trailer address its

viewer? How is it arranged? How does the trailer condense the film in terms of story, genre, argument? What

does it appropriate directly from the film itself and how does it reframe those fragments in the new context of

the trailer?

What are you learning about the genre of the film trailer? What are the conventions of the film trailer?

Make sure to have the Analytical Moves pdf available in class on Wednesday.

Wed,

1 Oct.

Work on presentations for class.

Mon,

6 Oct.

Rd pp 26-33 (“the method”) in the Writing Analytically “Analytical Moves” handout (unit 2 tab on Bb)

Download the Film Review Data Sheet (unit 2 tab on Bb)

Go into Netflix (or any other film site with members’ reviews, like amazon, or imdb, etc), and read a sample

of lay reviews (shoot for five if they’re long, or ten if they’re short) of your film.

Keep track of the patterns, trends, and anomalies in the reviews on the data sheet

Go online and find two published reviews [written by professional film critics] of your film.

Write a Bb post attending to the qualities of film review as a genre: what are you noticing? Is there a

difference between the lay reviews and the professional critic reviews? In what ways (if at all) are the

reviewers paying attention to the visual qualities of the film?

Wed,

8 Oct.

Compose and post your film review to a website by Sunday.

Post the same review to your blog, and then do a second post analyzing your choices in the review based on

an awareness of audience, persona, and medium.

Come to class with a short list of potential foci to guide your sustained visual analysis of your film.

Bring your observation notes to class. (Not doing any of this)

Instead, read pages 147-178 in WA and come to class with a tentative thesis statement

Mon,

13 Oct.

Create a “zero” draft of your unit writing. Shoot for two pages (500 wds). As with your unit 1 assignment,

remember that it’s a draft, so be gentle and generous with yourself; let the draft be as crappy and unsatisfying

as it needs to be at this early stage in the composing process.

Wed,

15 Oct.

Revise your documentary film analysis based on the feedback and discussion in class.

Post your thesis to the Bb discussion thread. Respond to two classmates’ theses by class time.

Prepare a list of questions/concerns about the essay for the class to consider and respond to. Post the list to

the Bb discussion thread.

Mon,

20 Oct.

Continue revising your essay. Compose your reflection. Read the drafts of the people in your group in

preparation for the meetings on Wednesday and Friday.

Wed,

22 Oct.

Draft conferences with Matt

Fri,

24 Oct.

Draft conferences with Matt; finalize your essay and reflection.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-20-320.jpg)

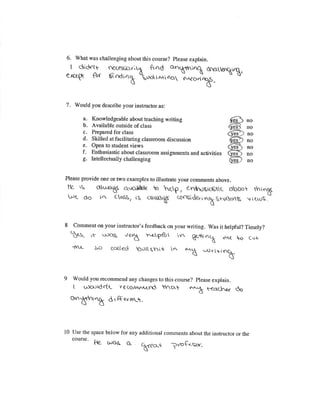

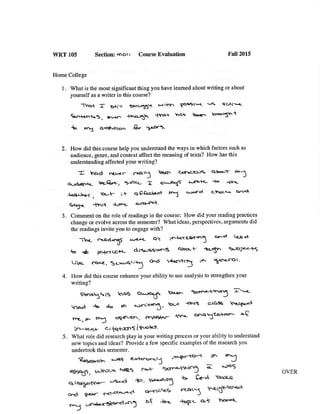

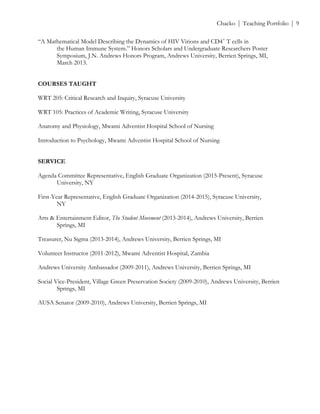

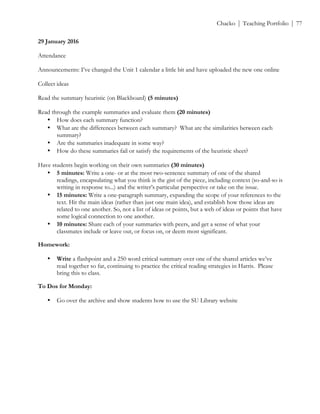

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 29

WRT 105: Unit 2 Calendar—Situating Visual Literacies

Date Homework (due the following class)

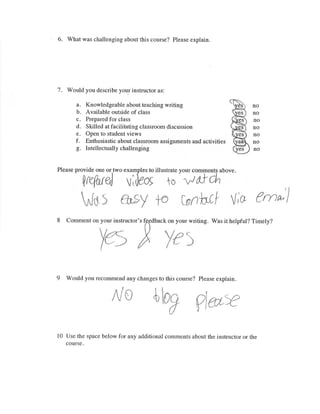

Mon,

28 Sept

Read and annotate pages 14-26 in Writing Analytically. Bring your annotated reading to class on Wednesday.

Watch the trailers for the following films:

• Paris is Burning: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fz5q1_ni8pA

• Nostalgia for the Light: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ok7f4MLL-Hk

• Miss Representation: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1784538/

• Last Train Home: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0N6vDotVNDo

Wed,

30 Sept

Read Pages 209-218 (Intro and Zemliansky) and pages 244-250 (Sturken & Cartwright) in chapter 5 of EaT.

Review the handout “Viewing Documentary Films” and bring it to class.

Fri,

2 Oct

Read and annotate Mark Strand’s “The Loneliness Factor” (pp. 257-260 in EaT). [the three Hopper paintings

Strand analyzes are in the chapter 5 glossy insert]

Choose to respond to either question #4 or #5 on page 261 and an in-class invention.

Watch your assigned film, and take good notes being mindful of the visual literacy concepts we have explored

so far.

Mon,

5 Oct.

Find, read, and annotate three reviews of your film. Bring these in hardcopy to class. Consider the genre of

the film review. What are some of the commonalities that you’re noticing across each of the reviews? How do

the reviews help you understand your film better?

Wed,

7 Oct.

Come prepared to answer this invention prompt: “Analyze the rhetorical structure of the trailer of your

film: i.e. how does the trailer attempt to persuade its viewers to go see the film? How does the trailer address

its viewer? How is it arranged? How does the trailer condense the film in terms of story, genre, argument?

What does it appropriate directly from the film itself and how does it reframe those fragments in the new

context of the trailer?”

Make sure to have the “Writing Analytically_p.14-25” pdf available in class on Wednesday.

Fri,

9 Oct.

Rd pp 26-33 (“the method”) in the Writing Analytically “Analytical Moves” handout (unit 2 tab on Bb).

(Extra Credit: 5 points): Write down a list of things you’re noticing from your film. Then identify a subject,

issue, scene, or sequence that you find interesting or strange. Write down at least 30 details down from your

film. Please bring your findings to class on Monday.

Mon,

12 Oct.

Read pages 147-178 in WA and come to class with a tentative thesis statement.

Wed,

14 Oct.

Revise your thesis statement based on the feedback you received from class.

Fri,

16 Oct.

Create a “zero” draft of your unit writing. Shoot for two pages (500 wds). As with your unit 1 assignment,

remember that it’s a draft, so be gentle and generous with yourself; let the draft be as crappy and unsatisfying

as it needs to be at this early stage in the composing process. Revise your documentary film analysis based on

the feedback and discussion in class.

Mon,

19 Oct.

Continue revising your essay.

Wed,

21 Oct.

Fri,

23 Oct.

Draft conferences

Mon,

26 Oct.

Draft conferences

Wed,

28 Oct.

Draft conferences; finalize your essay and reflection.

Fri,

30 Oct.

Submit final essay.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-29-320.jpg)

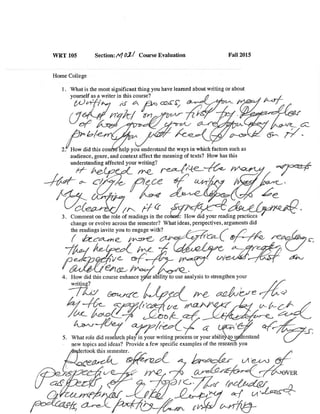

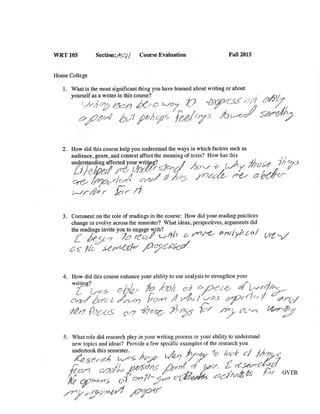

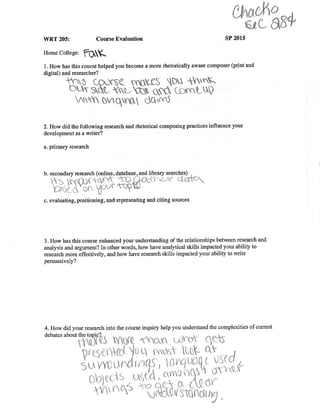

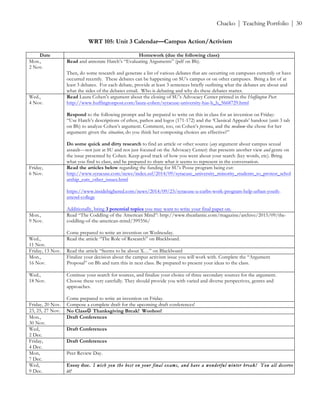

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 39

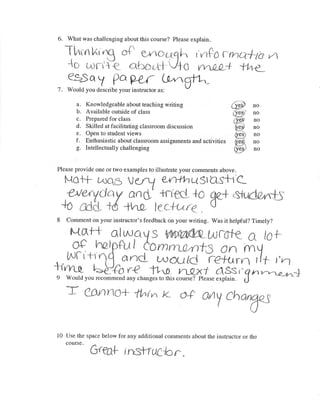

• Parents of the students

• Students who don’t like to party and feel that Castle Court was a huge waste of time and

energy

• DPS (Campus security)

• Management of Castle Court

• School administration/Faculty

3. Form Groups

Put students into groups and assign each group one stakeholder position. Have them read the article

carefully, make note of details specific to their position, and compose a one paragraph statement in

defense of their position to be shared with the rest of the class, using the group objectives below as

guidelines. [Teachers might consider ramping up the rhetorical exigence of the exercise, and tell

students that the stakeholders are participating in a public forum on the issue].

4. After sharing positions out loud, have students go

back to their statements and solidify and strengthen

them, and then propose a solution.

• Make sure students really tune into what the

opposing side says; How do different claims

strengthen your own argument?

5. Ask students to be prepared to speak to their new

understanding of rhetoric and persuasion: specifically in

what ways did your sense of what was and wasn’t

persuasive in the original article, or your awareness of

what other stakeholders think and believe, impact your

rhetorical approach? In other words, how has your

position grown stronger by being mindful of other

perspectives?

Homework:

• Continue your search for sources, and finalize your choice of three secondary sources for the

argument. Choose these very carefully. They should provide you with varied and diverse

perspectives, genres and approaches.

• Come to class with a brief synopsis of each source (100 words). This synopsis should

paraphrase and summarize the article’s main argument, why it’s relevant to your argument,

and the credibility of your source.

• Please type this out and give it to me next class period

• Come up with two questions related to the Advocacy Center

Group Objectives

Plan how you will you convince others by…

• Explaining what you want, and why.

• Considering the ramifications of your

position.

• Considering ulterior motives of other

stakeholders.

• Discussing your options for persuading.!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-39-320.jpg)

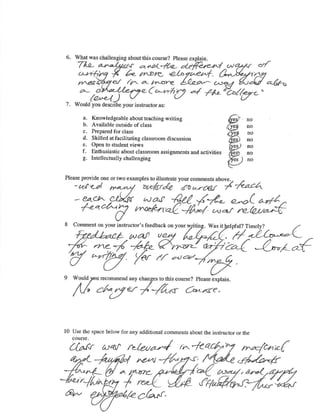

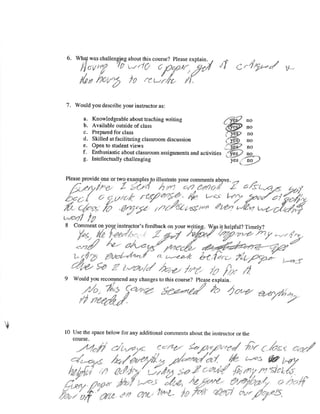

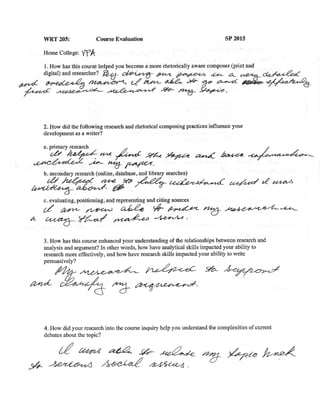

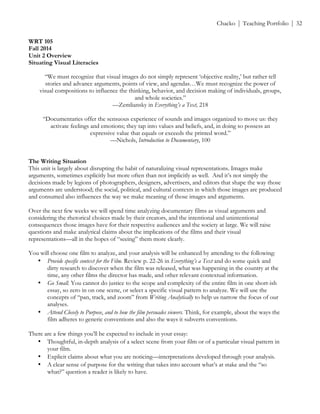

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 43

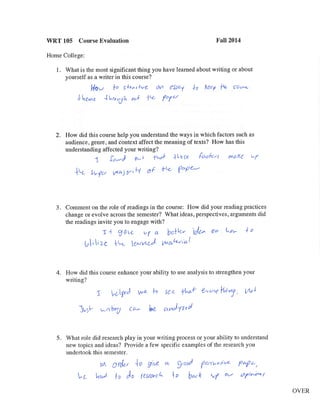

• Everything’s a text versus everything’s an image!

• What does Kennedy say about images and texts? They are the same. “Everything’s a text

and everything’s an image” (5.45)

• A wink can have different meanings

• “Slow looking”# what does he mean?

o Looking, seeing, analyzing, and then interpret it (construct meaning from it)

o What does interpret mean?

o We need the alphabet and grammar of visual literacy

• “We need to train our ability to construct meaning from images”

For Discussion:

• What are your questions about visual literacy?

• What does it mean to be visually literate?

• Why is it important to be visually literate?

• How do we develop visual literacy?

• How does our thinking of images as rhetorical tools that persuade help us to develop visual

literacy?

• What are some the things that Zemliansky looks at when conducting a reading of a visual

text? What does he take note of in order to reach a claim about the picture? (page 214)

• What is Zemlianksy’s understanding of context? How does context help Zemliansky

comprehend the picture? How do we understand context? (216)

Homework

• Come prepared to think about the Sturken and Cartwright piece

• Read and annotate Mark Strand’s “The Loneliness Factor” (pp. 257-260 in EaT). [the three

Hopper paintings Strand analyzes are in the chapter 5 glossy insert]

• Choose to respond to either question #4 or #5 on page 261 and an in-class invention.

• Watch your assigned film, and take good notes being mindful of the visual literacy concepts

we have explored so far. As you watch your film, what things that you’re finding interesting,

compelling, or strange? What are the binaries, anomalies, and patterns you’re noticing?

!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-43-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 50

[Student’s Name Left Blank]:

I love how you engage with the key concepts of literacy, mode, medium, and genre. I can tell

you’ve thought about these ideas, and how you can apply them to your own writing practice.

Firstly, I enjoyed your blog. The website is navigable, uncluttered, and very aesthetically pleasing. I

love the title of your blog: “My Orange Journey: Massachusetts Born, Syracuse Living.” I love the

notion of journey inherent in your blog’s title. It’s compelling, authentic, and sincere. Your photo is

also very attractive!

I really enjoyed listening to your “This I Believe” essay. I love your emphasis on teamwork, and that

you highlight the importance of your teammates in a sport that is individualist by nature. I also

greatly enjoyed your concluding paragraph and how you connect it to your opening claim of “I

believe in the power of a team.” Additionally, your thesis claim is obviously, cogent, and effectively

gets your point across. I have a few suggestions for your “TIB” essay. I would encourage you to be

a little more specific in your narration. You discuss how a huge asset in your life was your coach

and how he was a great resource. I think this is a great way of building off your idea of teamwork,

but I think describing instances of your interactions with your coach would increase the emotional

draw of your essay. Do you have any specific stories?

For consideration:

• You make many generalized claims, but none of these claims are backed by any specific

evidence. You state that “One of the biggest values of a team is a coach,” but you don’t

provide any specific evidence. You tell the reader what’s important, but you don’t show the

reader. What are you thinking, and how are you reacting to situations?

• On your reflection, again what specific evidence do you provide? What are specific

examples that can substantiate your claims?

• Watch your grammar and syntax. This is very important!

I enjoyed reading your reflection and essay! Thanks!

This I Believe/Invention Work: B

Reflection: B+](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-50-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 51

[Student’s Name Left Blank]:

Thank you so much for your essay. I found your thesis to be clear and concise, which is excellent! I

think the causal relation between the parents and children was a good idea to write on. Additionally,

I really appreciated your definitions of the various film terms you used. This was very helpful for

myself as the reader, and it shows your engagement with the language of filmmaking. Thanks for

taking the time to familiarize yourself with the terminology. Also, you provide ample amounts of

evidence from the film in your paper. By including the many, many quotes you did, you ensure that

your argument is rooted directly in the film. Nicely done!

Here are some ideas that might improve your essay. Firstly, I wasn’t entirely sure how your

paragraphs dealing with Suquin and Chinghua’s struggles were related to your thesis. After reading

through your paper in its entirety, why you chose to write about them became apparent. However,

those paragraphs lacked information relating to the thesis and why they were relevant. For your

next paper, really focus on how each component of your argument relates to the main claim in

general. Additionally, your introduction paragraph was a little sparse with contextual information.

Some historical and cultural information on China’s economy would have been very helpful as we

understand the relationship between Qin and her parents. You have a paragraph embedded in the

middle of your essay that begins with “Lixin Fan does not approach Qin’s position on remaining in

school versus becoming a migrant worker as her parents have…” This whole paragraph is a very

important piece of information for your argument, and I feel it would have served really well in the

introduction of your paper. Having robust introductory paragraphs allows the reader to understand

your paper’s structure and your rationale to organize the way in which you did. Finally, where was

your paper’s title? That’s so important in alerting the reader to the general subject matter of a paper.

Your reflection made some interesting points. However, there were many claims that were not

explained as sufficiently as I would have liked. Please look at my comments for some of the places I

found that could have used a bit more explication. I think your quote that “once I can educate

someone else on the content of that specific text, I believe I qualify as being visually literate” is

especially interesting. What are you implying there? Is visual literacy something you gain from

writing a paper once, or is it a developing process? That makes me consider what literacy means.

Additionally, your description of your composing process was very thorough. Nicely done! I would

have liked a bit more thoughts on our class activity. Did what we say in class help you with

becoming more literate?

Thanks again!

Unit 2 Paper: B+

Unit 2 Reflection: A-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-51-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 52

[Student’s Name Left Blank]:

Your essay was very engaging, thoughtful, and well-written. I think your writing has certainly

improved over the semester, so nicely done! I especially really appreciated how in-depth your

research was. You utilized a large number of sources that made your paper’s argument robust. I

also think you did a fine job logically tying your paragraphs together. As a reader, I found it very

easy to go from one paragraph to the next. That’s a great skill to have and to be conscious of.

Here are a few suggestions I have for you that I hope will serve you as you continue in English:

First, I think your thesis could be a bit more refined and less wordy. Make your prose as sharp and

clear as possible. Eliminate any unnecessary words, such as “acts as an odd against the mantra to

American capitalism.” I found that phrase to be distracting and actually took away from what you

were trying to argue. Your thesis is the most crucial component of your paper. Eliminate all

“fluffy” words you feel don’t add to the clarity of your claim. While some “fluff” is fine in other

parts of your paper, don’t have any in your thesis.

Second, avoid any overly-hyperbolic statements such as “Although there is a six-month grace period

after graduation, somehow debt catches up, creating a lifetime of money that needs to be

reimbursed” (3). While that may be true, I’d encourage you to tone your writing down a little more.

I even think a source to back up that claim would be great. For a claim that is that huge, I think a

source would be really excellent. You don’t want readers getting irritated at you for making, what

seems to be, a huge claim. If you have a source that backs up that idea, then use it. It takes the

pressure off of you and puts it on another person.

Third, always provide some context before and after quotations. On page 4, you included a very

smart quote that goes “There is a certain irony that those who were expected to benefit most from

expanded college access are also most vulnerable to the risks of carrying too much debt.” I think it

was very wise of you to include that point, and I understand why you placed it there. However,

always couch quotes with your own words before and after the quote that indicate why you included

the quote and why it’s relevant to your argument. Also, try and avoid ending paragraphs with

quotes. Try and end every paragraph with your own words.

Fourth, you include some great counter-arguments to your own. However, I didn’t see you

rebutting those claims. To make your paper as rhetorically sharp as possible, always make sure to

address those who oppose your side but then explain why those arguments aren’t valid.

Finally, and perhaps I didn’t explain this well enough in class, but always have a works cited page. If

I didn’t address this adequately during class time, then I apologize.

Thanks for a great semester! I always appreciate your smart comments in class. Keep up the good

work, and I wish you the best next semester! I hope my remarks are helpful for you as you continue

writing. Writing is a skill that we’re all improving and honing. I’m still learning so much myself.

Unit 3 Paper: A

Unit 3 Reflection: A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-52-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 53

[Student’s Name Left Blank]:

Thanks for your paper, which was successful in a number of ways. Here are some of your paper’s

strengths:

• Your thesis was strong and well-worded. I think it successfully gave me a roadmap of your

paper, and it was definitely something you could argue. You used especially strong verbs

(such as juxtapose), and it contained a lot of energy. Nicely done!

• Also, your prose is, for the most part, very clear and articulate. I didn’t notice too many

grammatical errors either. That’s very important!

• You use a lot of strong evidence.

• Your paper’s logical structure was also excellent!

Here are some things to improve:

• While you have pretty solid topic sentences, I think you could make some of them even

more explicit. Tell the reader what this paragraph is going to be about and be very up front

about it. Every paragraph should begin with a clearly sense of its own purpose and its

relation to your argument.

• Watch your personal pronoun usage. I would not use words such as “you,” “me,” “I,” or

“we” as much as you do. Personal pronouns should be used minimally, if used at all.

• Develop your “so what” answer a bit more. Why is your thinking about the text important

or relevant? What’s the significance of your paper? Why should the reader care? What are

the implications of a film that relies so heavily on gender stereotypes? Are there any

problems with that?

• At times, I felt like your analysis wandered a little bit from your topic sentences. For

example, I wasn’t entirely sure how your interest in the footage of gears and telescopes

related to your claim on the men’s profession. Remind your reader throughout your

paragraph how your evidence relates to your topic sentence or thesis in some way.

• Avoid using the same word in the same sentence. I noticed that a few times.

• At times, I felt you rushed through your logic and didn’t adequately explain how your

evidence related to your topic sentence. For example, on page four you talk about the

doctor who was imprisoned under Pinochet’s regime. However, I wasn’t entirely sure what

you were trying to tell the reader. What was the point of that paragraph?

• Also, the first full paragraph on page four seemed to contradict itself a little bit. You talk

about how the men and women are separate which supports your claims of the film

promoting gender stereotypes, but then you switch to talking about how the men and

women are connected in some ways, which undermines your claims. Make sure you don’t

contradict your claims. That destroys your credibility!

Overall, nicely done! You made some really smart claims and developed some excellent analytical

points!

Final Grade: A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-53-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 54

[Student’s Name Left Blank]:

Thanks for your paper. Here are some of the strengths I noticed in your writing:

• Your thesis was strong and well worded. I think it successfully gave me a roadmap of your

paper, and it was definitely something you could argue. Nicely done!

• I really like that you bring in the concept of codifying in your analysis. That was especially

useful for the reader, and it really helped advance your argument.

• There are some really fine moments of analysis in your writing. You really do a nice job at

explicating some of the meanings in the film. This is very helpful for the reader, so nicely

done.

• You also ground your analysis in the film’s specifics. You furnish your paper with a lot of

evidence from the film, which is great!

• You don’t use any large generalizations, and all of your claims are grounded in solid

evidence.

Here are some of the ways you can improve your writing:

• Italicize film titles

• Make sure your pronoun usage is very clear. I noticed that there were some parts where I

wasn’t sure whom or what your pronouns were referring to. Make sure that you’re also

using the proper noun at times to make sure everything is clear for the reader.

• Don’t repeat the same word in the same sentence or too closely in the same part of the

paper.

• Really, the biggest suggestion I have for you is some of your syntax. A few sentences were a

little confusing and jarring for the reader. I note those in your paper. In the future, ensure

that each sentence is completely readable. Perhaps read your draft aloud before submission.

This will help you to catch any sentence that jarring or confusing.

• While your paper makes good use of topic sentences in that help guide your reader in some

places, I sometimes felt that your paragraphs wandered away from the original topic

sentence.

• Ask yourself, “What is the point of the paragraph?” If you find that your ideas seem a bit

contradictory, then that’s a good indicator that some of those ideas that are contradictory

should be in a separate paragraph.

• I think you have some issues with commas. Let’s get that sorted out a bit better, shall we?

There are also ample resources on the internet that can help you. I can also help!

• Sometimes your paragraphs didn’t have a clear topic sentence. This indicates that you didn’t

know exactly what your paragraph was doing or trying to achieve. It also makes it more

challenging for the reader. Make sure that you have clear topic sentences. For example,

your middle paragraph on page four lacked a clear topic sentence. What do you want your

reader to take away from this paragraph?

Overall, nicely done! You really make some smart insights!

Final Grade: B+](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-54-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 91

[Student’s Name Removed]:

Thanks so much for your thoughtful and very articulate paper. I think you did a number of things

especially well, and I just wanted to mention them here:

• I think your thesis was quite successful. It contains good tension and it provides a good

framework for your paper’s logical structure. I really like how your paper makes me think

about how South Park’s characters still operate under white hegemony. Even though they

question white hegemony, they inadvertently maintain it to some extent by not showing

compassion and empathy to the immigrants. I think that demonstrates nuance in your

thinking, so nicely done!

• Your definition of white hegemony and how it constructs ideas of what is normal in

American society was incredibly helpful for me as the reader. I think this was a good

sentence: “A core principle to white hegemony is viewing the white actions and viewpoints

as the governing social norms of a society.” That was very much needed in order for me to

understand how you were thinking of South Parks’s characters still operating under a white

hegemonic ideology. Good job!

• Perhaps my favorite part of your paper was when you mention the lack of empathy any of

South Park’s characters give to any of the immigrants. This was an especially good sentence:

“While this is also a commentary on conservative views of immigration, underneath the

apparent topic is an underlying lack of empathy and compassion shown for the Goobacks

who are working equally as hard as the men they replaced but for completely different

means. Though the actions and dialogue of the show’s main characters, South Park is further

enforcing and exemplifying the white hegemonic society it intends to depict.” I think that

was a great reminder about how not to be oppressive. Show empathy to people! I’m so glad

that you capitalized on this!

• I love how you’re reacting to quotes, placing yourself in dialogue with various writers. That’s

a great skill you have and for you to keep developing. For example, this was a great

response: “While this quote discusses two parties in the South Park discourse, there should be

three…” That’s exactly the type of thinking to keep up! Keep responding to and furthering

other people’s ideas, showing your reader where they could be improved!

Here are a few ways I think your writing could improve:

• Make sure your sentences are absolutely clear. I noticed a few times where your sentence

structure was a little confusing or perhaps your idea was unfinished. Here’s one example I

found: “While the show mirrors a full spectrum of American viewpoints, South Park intends

to portray their audience.” What do you mean by that? It seems as if the next sentence after

this one will explain what you meant, but I don’t think it did. Make sure your sentences are

fully finished so you don’t leave your reader hanging.

• In your thesis, you mention how the show reinforces negative stereotypes. What kinds of

stereotypes? Make is a little more specific to the topics you’re addressing in the episode,

specifically immigrants and white conservatives/liberals.

• I think it would be helpful if you mentioned the connection between goobacks and wetbacks

and how the show is directly referencing actual immigrant stereotypes that are held.

• Make sure each and every quote is working to advance your argument in some way. For

example, your Chidester quote doesn’t seem especially helpful. Make sure that you elaborate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-91-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 93

[Student’s Name Removed]:

What an interesting paper! I love the complex thinking you show. You arrive at some really neat

and intelligent ideas. Your paper is thought provoking in a number of ways. I want to highlight

some of your paper’s biggest strengths:

• I love your thesis. Basically, it’s spot on and so smart. Over the semester, I have definitely

seen the transformation in your thinking. As we’ve met, you’re thoughts have definitely

progressed, and you have some really solid and intriguing thoughts in your final paper. I

would say your thinking over the course of the semester has evolved, and it shows in your

paper. Good job! Not only is your thesis interesting, but it contains some good tension.

Your verbs are active and contain lots of energy. Nicely done!

• I like that you capitalized on Avatar. That’s definitely not a connection I would have thought

of, but you thought about it well. I think it works well with your paper’s main argument

about America’s hypocrisy and its deluded sense of identity. You show sophistication in

your thinking!

• I also enjoyed your discussion of Borat at the end of your paper. Your quote you use that

begins with: “The movie isn’t showing Kazakhstan…” was an excellent rhetorical move on

your part. It definitely elevated your paper’s persuasiveness.

• Overall, I thought the components of the film that you chose to include were really good.

You selected really strong parts of the movie that made your analysis really persuasive.

Here are some ways to improve your paper:

• Your introduction could focus a little bit more on America and how it views itself and

others. Since your thesis is all about how The Dictator ridicules America’s assumptions of

itself, it would be helpful if your introduction begin thinking about the issue so it would lead

nicely to your thesis.

• I would definitely shorten the section on the movie’s criticism (pages 2-3) and instead focus

more of your energy on America’s views of itself. Focus more on America in your paper. I

think the movie’s critics could have been put into one paragraph. Also, make sure that you

don’t make really easy categories. On page 3, you mention that Americans found the movie

funny but non-Americans didn’t, “Most of the criticism about this movie came from

foreigners of the United States, while Americans loved it.” I don’t actually think this could

be true. There were numerous Americans that didn’t find the move hilarious, so make sure

your writing reflects that. Don’t lump people into big categories and assume those

categories hold true for everyone.

• You ask the reader many questions in your paper. A few are fine, but don’t depend too

much on asking questions. It’s distracting for the reader.

• Don’t address the audience too much. For example, you mention on page 3, “Yes, if you’re

an American, you may think the US government is the best and it shouldn’t be made fun

of.” Don’t rely too much on the use of “you” in your writing. The less you use “you” then

the better your academic writing will be.

• With your quote on pages 3-4, which is a great quote, I think you could definitely talk about

it more. Push your thinking a little more. Also, where is it coming from? You give no

citation, and I therefore don’t know what source you’re using. Always provide in-text

citations for your reader.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-93-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 95

[Student’s Name Removed]:

For the most part, I think you do a lovely job summarizing your articles. In most of them, I

identified your critical stances on the various issues and ideas presented by the authors. You

correctly identify the author’s aims, project, and main ideas. Here are some things I really enjoyed in

your writing:

• I love how identify the pros and cons of self-deprecation, especially when you state: “She

explores whether these jokes are a positive step for the minority groups because they entail

ownership of these stereotypes or if they are a step in the entirely wrong direction.” There

are no easy answers, and while humor can employ one type of comedic strategy to make a

point, there are always drawbacks too.

• I also enjoyed how you identified the tension that some comedians are under to provide

laughs and also say something meaningful about culture.

• Your questions were very good, and I think they could lead you to some interesting

conclusions!

Here are some things I identified that might help you in your future writing:

• Make sure that you vary your sentence structure. In the “Just Joking?” summary, I noticed

that you began multiple sentences with “she says” or “she speaks.” While this is a perfectly

acceptable way to begin a sentence, don’t begin every sentence the same way since it can be

monotonous for the reader.

• Watch for sentence clarity. For example, the sentence in your reflection “In another article,

the author pondered if simply because a woman was performing on a major outlet that it

was a feminist movement and that’s something that intrigues me,” is a bit confusing and

jarring for the reader. There are multiple ideas embedded in this sentence, so perhaps you

could make two sentences out of it for clarity’s sake. Can we tweak it to make it a bit more

readable?

• In the “Funny Girl” summary, I lost the sense of Stein’s project and the approaches he’s

using to convey his point. I understood the author’s project better in your other summaries,

but I wasn’t as sure in this one.

Overall, nicely done! I love how engaged you are in class, and you always have very intelligent and

insightful things to say. Keep up the good work, and I look forward to working with you the rest of

the semester!

Unit 1 Grade: A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-95-320.jpg)

![! Chacko | Teaching Portfolio | 96

[Student’s Name Removed]:

Thanks for your portfolio, and there were many successful things I noticed in your writing. I just

wanted to point a few of those things out. Perhaps you can use them in your final paper somehow?:

• In the “Funny Girl” summary, I think you did a great job pointing out the irony between

Amy Schumer’s appearance and the content of her comedy. I like how you think about how

that allows her to talk about women’s equality. Nicely noticed!

• In the “Performing Marginality” summary, I think you nicely notice that not everyone will

interpret humor the same way, “By disguising the real problems with self-depreciative

humor, the deeper message can be missed, being eclipsed by the joke and leaving audiences

thinking about how a comedian like Barr is crazy and fat, rather than powerful, intelligent,

and brilliant.” I love how you’re noticing the unintentional side effects of a certain comedic

style. What are the dangers to performing a certain way? You always have to mindful of

your audience, and ultimately it’s the individual that interprets comedy as meaningful,

impactful, or just shallow.

• Here’s another nugget of smart insight I noticed from your “Just Joking?” summary: “When

someone uses the phrase ‘just joking it removes responsibility over whatever the person has

just said because they can conceal any ludicrous social beliefs of themselves or the culture

they live in by calling it a joke.” That was very smart, Matt! I hadn’t thought of it in those

terms as a way of evading responsibility.

Here are some ways to improve your writing:

• At times, I didn’t understand how you understood what the author of the article was

attempting to do. For example, in the “Funny Girl” summary, I lost the sense of Stein’s

project and the approaches he’s using to convey his point. I understood the author’s

project better in your other summaries, but I wasn’t as sure in this one.

• Watch making large generalizations, such as “Freedom of expression is one of the most

crucial components in the maintenance of a healthy democracy.” Instead of writing two

sentences on general subjects that your readers are probably aware of, I’d instead begin

immediately with the article and state what it’s attempting to do. Always ground your

writing in what the author of the article is trying to say and what you conclude from it. I

would have liked it better if you started each summary with the articles and what they are

doing. I hope that makes sense.

• While your prose is, for the most part, very clear and readable, there were a few sentences

that seemed a bit jarring. For example, “After reading several of these articles, there are

many interesting points about comedy, that might go over the heads of the people

consuming the humor, but these points subconsciously alter the views of that culture based

on the jokes being presented.” Can we reword this sentence and perhaps shorten it? It’s

very long, and I think we can make it more concise.

In general, you did a fine job articulating the main points of the articles. You also provided some

interesting insight on what these articles are doing, so nicely done!

Unit 1 Grade: A-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/08ff8e27-d0d3-4c71-89cc-136d7c954856-170101203824/85/Teaching-Portfolio_Chacko-96-320.jpg)