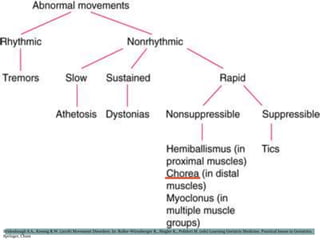

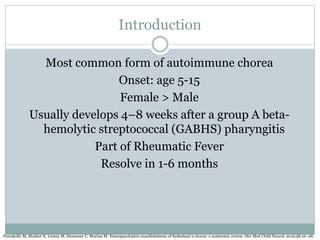

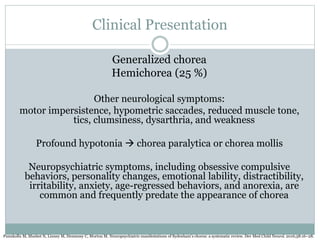

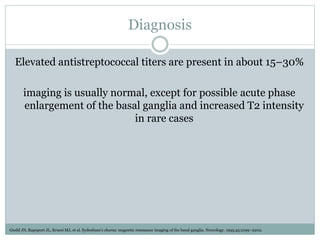

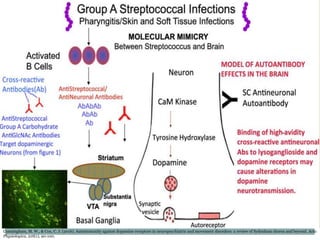

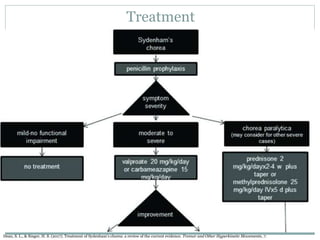

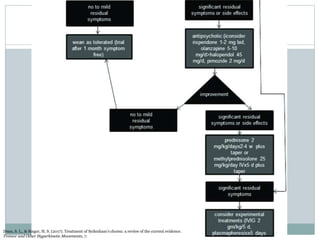

Sydenham's chorea is a movement disorder that is the most common form of autoimmune chorea. It typically develops in children between ages 5-15 after a Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection and is part of rheumatic fever. Symptoms include generalized chorea and other neurological symptoms like motor impersistence. Diagnosis involves looking for elevated antistreptococcal titers and imaging may show basal ganglia enlargement. Treatment considers severity, requirements, availability, cost, evidence and side effects. It is thought to be caused by molecular mimicry between streptococcal and human proteins that leads to an autoimmune response.