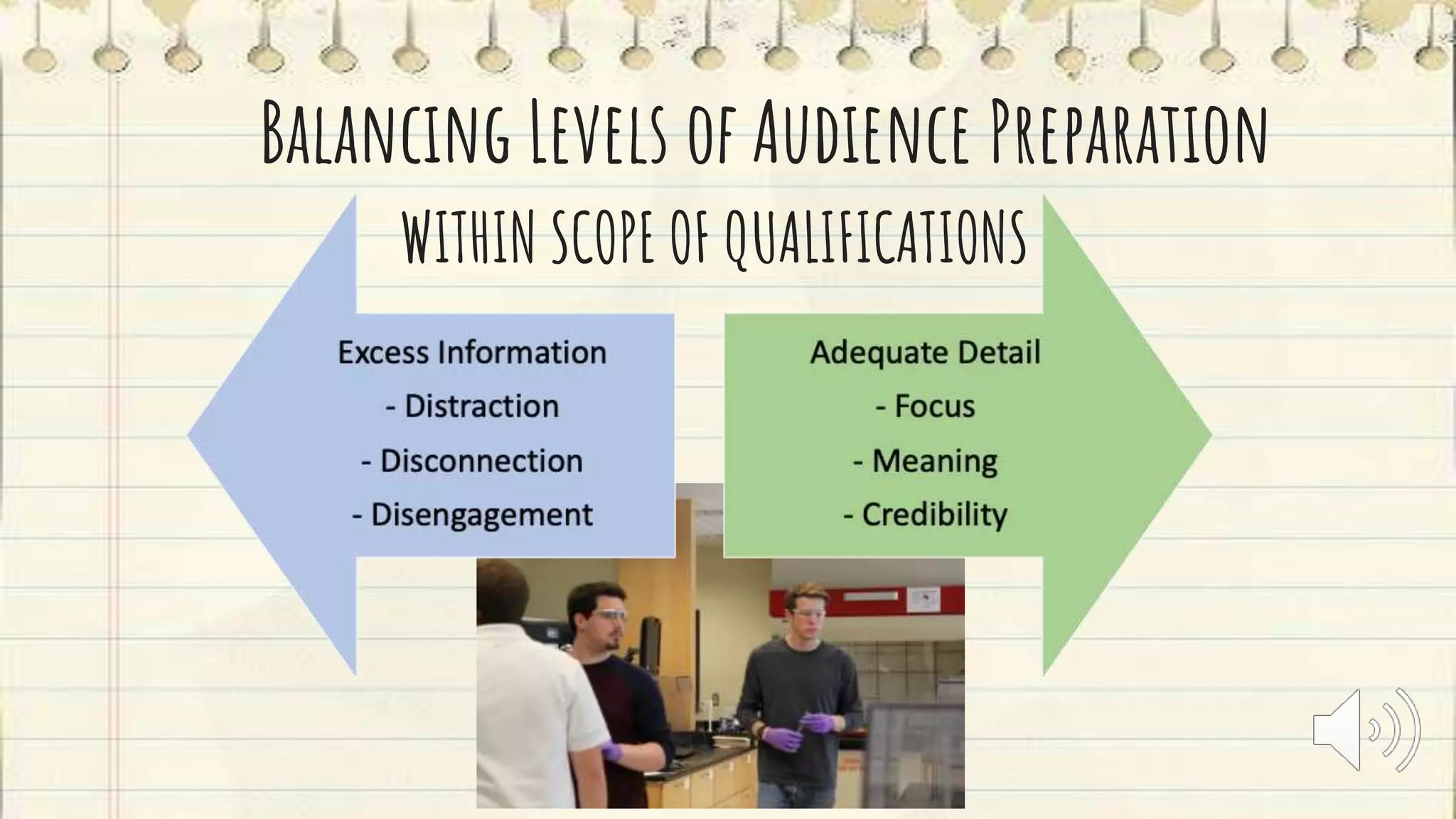

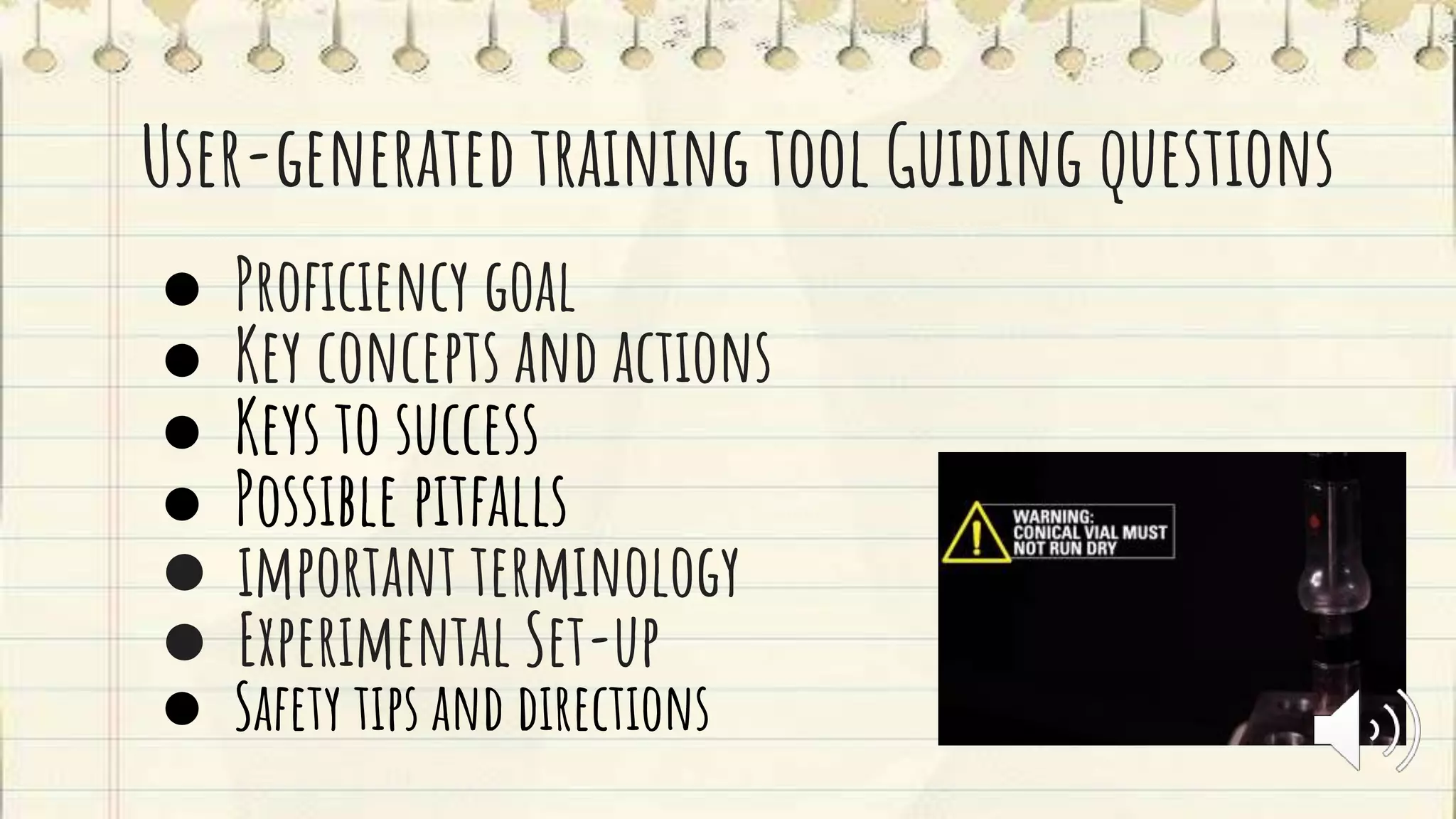

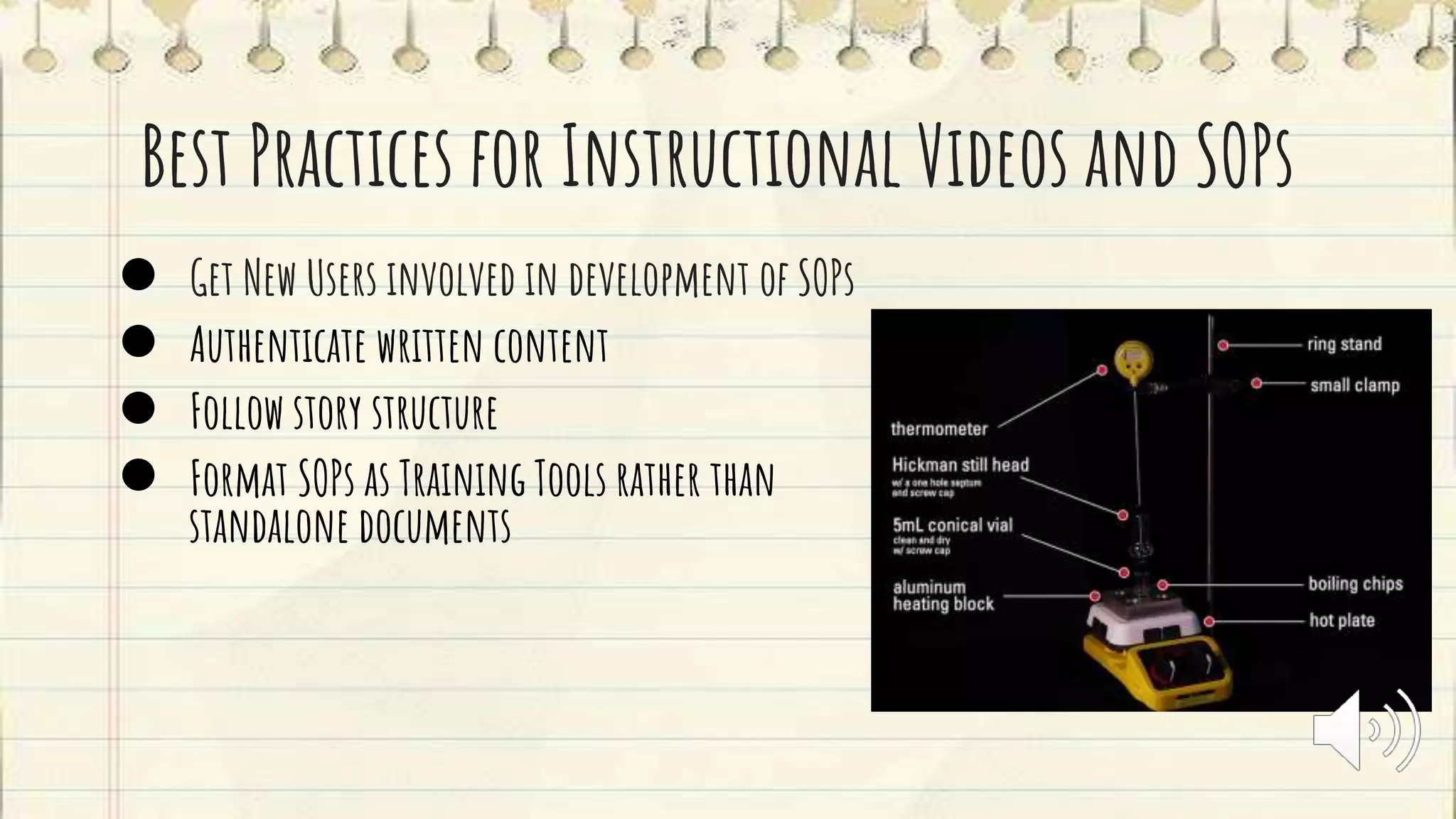

The document discusses the development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) in academic labs through student-generated videos at North Carolina State University. It emphasizes the importance of instructional design, audience engagement, and the use of story structure to create effective training tools. The document outlines best practices for creating SOPs, such as collaboration, user involvement, and the authentication of content.