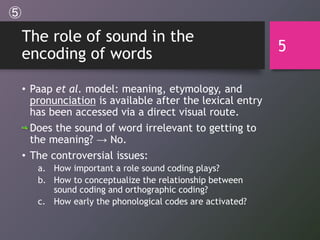

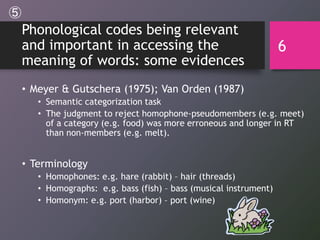

The document summarizes key topics from Chapter 3 of Psychology of Reading (2nd ed.) regarding word perception. It discusses:

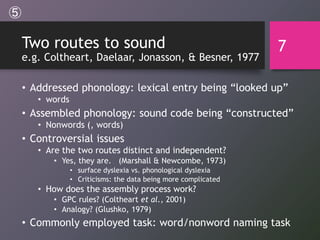

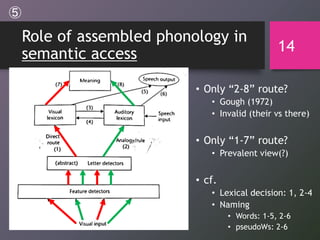

1) Two potential routes to accessing sound when reading words: an addressed route that retrieves a word's pronunciation directly and an assembled route that constructs pronunciation.

2) Evidence that both routes are involved in reading real words, not just one or the other. Assembled phonology plays an important role in semantic access of words.

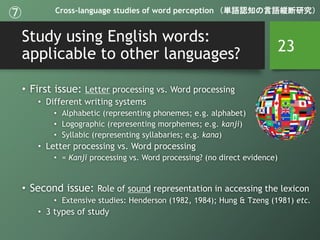

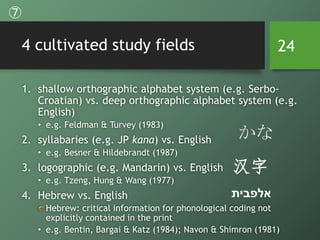

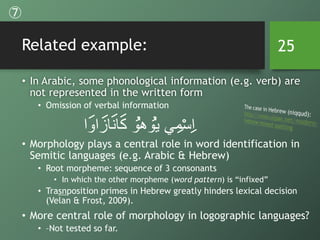

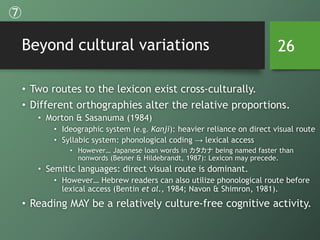

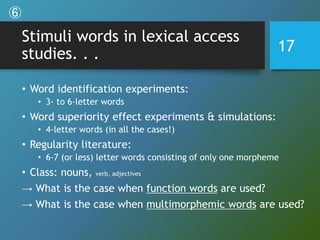

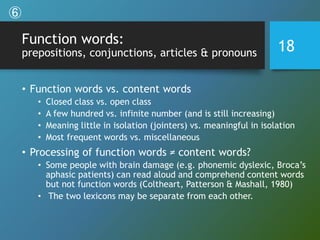

3) Processing of different word types like function words, multimorphemic words, and how models explain their recognition. Cross-language studies also show how orthography influences reliance on routes.

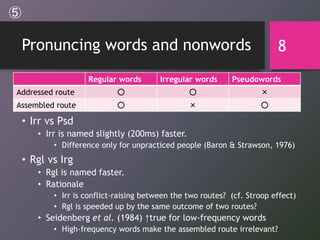

![Interactive [cooperate computation]

model

• single-system model + two distinct systems

• e.g. when the presentation of “one” activates:

• (assembly) /own/ /on/ /cone/

• (addressed) /wʌn/ & associated phonological codes

→ the lexical entry which gets the most summed activation is

identified as the word

• Can irregular words produce inhibition?

• Not really for mildly irregular words (majority; e.g. “pint”)

• True for wildly irregular words (minority; e.g. “choir”)

• Unusual orthographic structure can also be the factor.

12

⑤](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140622074228-phpapp01/85/_-12-320.jpg)

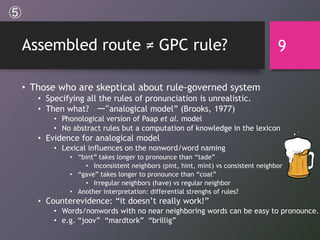

![Not only the addressed channel but

also assembled channel is used to

access the sounds of real words.

• Related issue: 2 routes to comprehend what is said:

• (a) sound of the speech and (b) visual information of the lips

• (a w/o b): talking on a phone

• (b w/o a): lip-reading of deaf people

• (b → a): McGurk Effect (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976)

• (a)/ba/ + (b)/ga/ → /da/ (highest total excitation from a & b)

• Lip information is integrated with (or even facilitates; Yoshida, 2009) the

sound information in processing speech.

• Assembled phonology in identifying high-frequency words*

• Masked priming study (Pollatsek, Perea & Carreiras, 2005)

• Early phonological effects detected even in high-freq word recog

• Bigger priming effect in [conal → CANAL] than in [cinal → CANAL]

13

⑤](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140622074228-phpapp01/85/_-13-320.jpg)

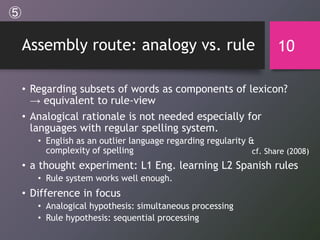

![Phonological involvement in the

access of the meaning of a word

• Is rule/analogy system involved in semantic access?

• Regularity effect in correct “Yes” responses in LDT: inconsistent

• Pseudohomophones of correct “No” responses in LDT: consistent

• E.g. “phocks” is slower than other nonwords.

• Problems:

• Any implication to lexical access of “real” words?

• pseudohomophone effect being an artifact (visuality)?

• ⇔ deep[phon.] dyslexic patients not showing the effect

• Meyer, Schvaneveldt & Ruddy (1974): the evidence

• [couch → touch] slower than [chair → touch] in LDT

• Problem: LDT does not ensure semantic access (e.g. Balota & Chumbley, 1984).

• How about semantic categorization task?

• Another interfering variable (robin vs penguin as a exemplar of birds)

• Van Orden, Johnson & Hale (1987); Lesch & Pollatsek (1998)

• False homophone pairs are slower & erroneous to respond “No.”

• e.g. pillow-bead cf. bead vs. head

15

⑤](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140622074228-phpapp01/85/_-15-320.jpg)

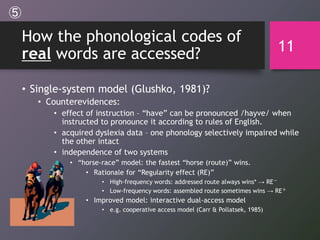

![More promising approach:

masked priming paradigm

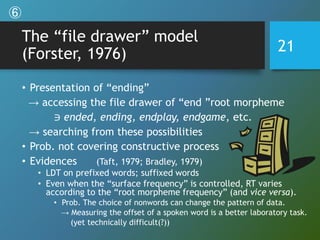

• Priming effect bigger for [CLEANER → clean] type of pairs

than for [BROTHER → broth] type of pairs.

• e.g. Feldman (2000); Pastizzo & Feldman (2002); Rastle, Davis, &

New (2004)

Morphemes play some role at a early stage of word

identification.

• Another rationale: suffixes (not morphemes) are extracted

as units early in word processing.

• Greater priming effect for [CORNER-corn] than for [BROTHEL-broth]

• Another possible methodology

• Eye movement measures in reading experiments

• To be continued in Chapter 5

22

⑥](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-140622074228-phpapp01/85/_-22-320.jpg)